Usagi Yojimbo has ended its run at Dark Horse. This is certainly an event to be marked. Even if it does not mean the end of the series as a whole (it has already moved to a new publisher in IDW – home of 1980’s cartoons and the masters of European comics); even if Dark Horse is not Usagi Yojimbo’s first home (the character premiered at an independent anthology, started an ongoing at Fantagraphics and spent a short time at Mirage). Usagi Yojimbo has been at Dark Horse for over twenty years and about 170 issue, not including one-shot specials and short stories. That’s a huge corpus of work. Seeing as we are at an end of era, it is time, once again, to give the series its due.

The wandering Rabbit-Ronin, on his eternal warrior-pilgrimage in a land much like historical Japan (if it was populated exclusively by anthropomorphized animals), is today very much as he was in first appearance in the furry-comics anthology Albedo Anthropomorphics #2 (November, 1984). It’s tempting to say that Usagi is a constant, that he is as he always was. Untrue, if only slightly. While the series has kept the same level of quality pretty much from the get-go (indeed if there is a ‘bad’ Usagi Yojimbo story I have yet to encounter it), you can still see Stan Sakai slowly figuring things out in the early stories. The series is a journey not so much to change the character, but to better understand what he is.

Early Usagi Yojimbo stories, the ones collected by Fantagraphics rather than Dark Horse, feature a cruder idea of the character and the world he inhabits: Easily recognized for what he will become eventually but still distinct enough in the difference to be noticeable (think of the early Peanuts stories, as Schultz was getting a handle on Snoopy). Usagi in these stories is not only more animal-like in appearance, but also more of a bastard. In these stories he is more cynical, prone to violence. In one early tale we see Usagi aping a particularly familiar gesture, made famous by Toshiro Mifune-scoundrel character from Seven Samurai (later Usagi is more likely to act in the vein of Takashi Shimura’s noble Kambi from that same film). Everything from his movement, to his gaze, to his very thoughts says violence.

Early on Sakai was obviously writing stuff he wanted to draw – so we got bits from Seven Samurai and Yojimbo (naturally), as well as clear homages to Zatoichi (a blind swords-pig) and Lone Wolf and Cub (Lone Goat and Kid). Godzilla makes an appearance – for no discernible reason other than Sakai really liking Godzilla.

There’s a slow-build towards the Usagi we now know and love - the noble hero willing to dedicate himself to save whatever unfortunate soul he encounters on the road. As that figure emerges from rough draft and the shout-out characters slowly clear the stages; Sakai’s own creations come to fore. Once Sakai found his sweet-spot, there was very little room for any farther transformation – side characters may be introduced and allowed to go through an arc, and even die when their role is fulfilled. The main characters however: Usagi, greedy bounty-hunter Gen, heroic retainer Tomoe, wise mentor Katsuichi, remain forever the same.

Despite decades-worth of adventures at this point, Usagi has barely changed, and even the various children-characters gained nary an inch in their height. The series does take place in a recognizable period in Japanese history, the military-ruled Shogunate. With the oft-mentioned ‘Black Ships’ of foreigners waiting anchoring ominously near the country’s shores, and with many a-ronin complaining bitterly about ‘the Shogun’s peace,’ we can probably mark the period as the Tokugawa Shogunate. This is a world floating in an abstract but well-researched notion of Japanese history and myth. There are noble samurai and roaming bandits, ninjas dressed for stage in the traditional all-black pajamas, monsters, demons and dinosaurs (oh my!).

Of course, this is not new to American-style comics. From superhero comics (in)famous ‘illusion of change’ to the never-ending childhood days of Peanuts and Nancy. Comics, un-dependent as they are on physical portrayal, and birthed out of mass-serialization (no matter what Scott McCloud might say) have many more examples of time standing still. Or, rather, Alice in Wonderland-like running, as fast as possible, just to stay in place. As Umberto Eco noted in his seminal “The Myth of Superman”:

“The mythological character of comic strips finds himself in this singular situation: he must be an archetype, the totality of certain collective aspirations, and therefore, he must necessarily become immobilized in an emblematic and fixed nature which renders him easily recognizable (this is what happens to Superman); but since he is marketed in the sphere of a "romantic" production for a public that consumes "romances," he must be subjected to a development which is typical, as we have seen, of novelistic characters.”

The interesting thing about Usagi Yojimbo is how it takes this issue and makes it one of the thematic elements of the series, perhaps even the core theme. The characters of this world are bound and chained into their identities just as much as they are bound by conventions of genre and the physical space of the panel on the page. Despite being not just a ‘protagonist’ but an actual hero, Miyamoto Usagi is very much of his period. This is most fully revealed in his approach to matters of class and fate. As he tells one earnest peasant boy who seeks to better himself in "A Life of Mush" (Usagi Yojimbo #32)- “Peasants cannot become samurai warriors. Be content with what you are.” Later in the story the boy is quickly exposed to the violence of samurai life and flees back to the safety of his peasant existence.

Usagi, and many other characters throughout the series, know they are figuratively ‘trapped', but they have no intention of changing their station, nor any notion that such a thing is even possible. In “Shizukiri” (issue #95) a hired assassin tries to convince his prostitute wife that if he takes this one last job they’ll be set for life

The reader knows, due to the nature of these stories, that ‘one last job’ never pans out. Indeed, the wife proves correct (her husband keeps living the life of hired killer) while not seeing the forest for the trees (she dies during his botched assassination attempt).

What’s interesting about the way Sakai presents these stories is that he makes no judgment – letting the actions speak for themselves. He neither venerates the honor-obsessed nor berates them for their historically-perceived awfulness. The main plot engine in “Shizukiri” is the murder of a begger by a samurai, trying out his new blade. Its only ‘murder’ in the eyes of the reader. As far that society is concerned a samurai killing a begger is somewhat akin to swatting a fly. Not only can it be justified, it is not even that worth commenting on (that is, unless the flies bit back by pooling their resources and hiring a killer).

Usagi, for all his commitment to the values of chivalry, would not think to rebel against such behavior. He might be aghast that some samurai are behaving in such a manner, failing to uphold to the highest values of bushido. But he would not fight against the system that allows the samurai the right to be kill peasants. As a general rule, most of the samurai characters we see throughout the series fail to live-up to the ideals of bushido. The series seems to say that such honor-bound systems only works when all people are equally noble and fails utterly once the bastards appear.

It is also important to remember that the Warrior’s Code Usagi labors under was only formalized centuries after samurai came to be as a class. The characters romanticize the code, but the series often subverts it; as following it strictly can lead to results that are anything from tragic to foolish. The reader thus can cheer on characters who make conscious decision to abandon the code, rather than reject it out of momentary necessity.

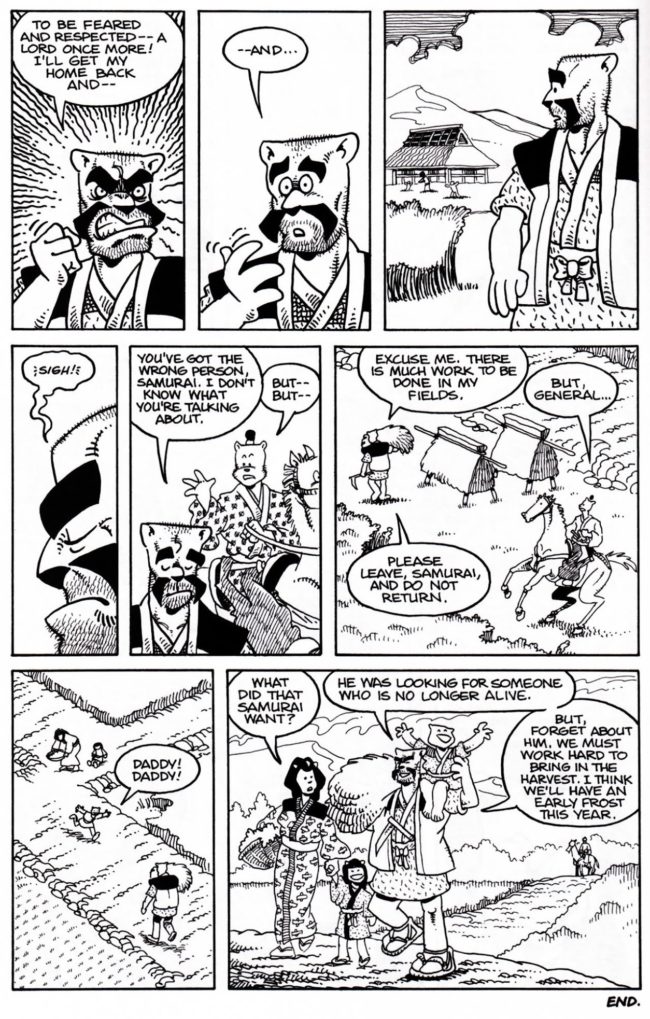

My personal favorite story in the whole saga so far is the short story “The Patience of the Spider” (part of issue #10) which sees a general masquerading as a farmer for several years, biding his time to take his enemies by surprise. When opportunity to regain his status finally knocks he realizes that he would rather toil the land than raise a sword again. It’s a simple story, one can easily see the conclusion long before the protagonist reaches it, but the storytelling is of such elegant simplicity that it is hard to resist. Sakai knows this will work because although the reader may expect this ending, it goes against the core principle of the society depicted. General Ikeda’s choice is a small moment in a small story – but it has far-reaching impact because we have come to understand the weight of class structure in the society he lives in.

The classic text Hagakure (they will teach you that book if so much as glance at a ‘History of Japan’ course) was only published in 18th century, while the country was relaxing under The Shogun’s Peace. Though I would not pretend to be anything close to a scholar, the accepted version these days is that this book existed to give the restless warrior class something to focus on while no wars where taking place. Noble samurai are like noble knights, mostly a myth; but it’s a myth that’s useful to maintain because it keeps the nobility on their best behavior (in theory).

Early in the Hagakure, Yamamoto Tsunetomo basically admits that he is writing something to aspire to rather than something achievable: “Today, however, there are no models of good retainers. In light of this, it would be good to make a model and to learn from that.” This comes after a rather hilarious passage in which he laments how kids these days, that being the 1800’s, are mostly into sex and booze and less into dying for their lord. Usagi is certainly an exemplifier of the warrior’s code, and respects those who uphold it, even if their behavior would appear foolish to the outside observer.

In “The Fortress” (issue #116) Usagi observes a group of samurai walking with their retainer into a trap and tries to warn them to no avail.

Usagi: “I told you – you’re heading into a trap. Why not turn back just to be safe?”

Morikawa: “That would be a show of cowardice, and could be seen as a rejection of the shogun’s gift. We must go on, even if we know we are walking to our death.”

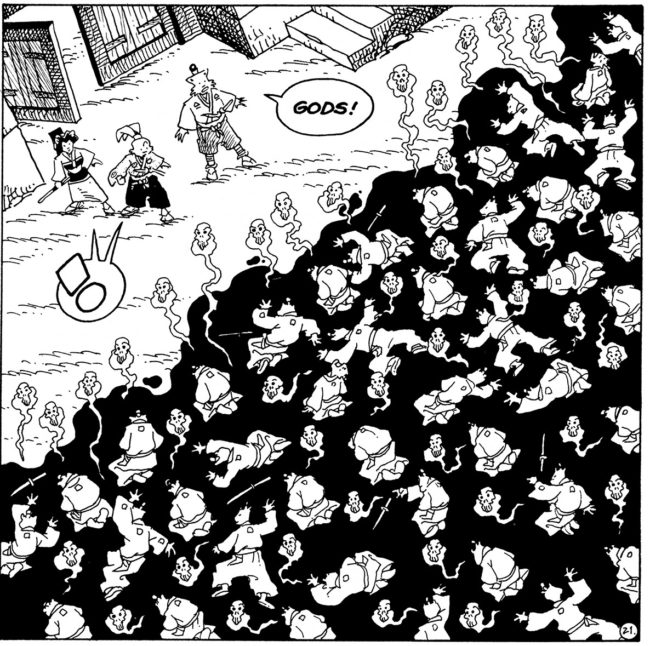

The trap is sprung. Many of the samurai die, and their retainer ends up dead as well. Tough not before he steps into the castle gifted to him by the Shogun and makes his claim on it. Within the fortress there is another vision of honor-induced death – the samurai belonging to the previous owner of the castle chose to commit ritual suicide as a protest against their home being given away to another lord.

That is a particularly neat shot. Sakai is very good at keeping the stories focused on a core small group of characters and shocking you every once in a while with his skill at drawing large crowds. He never pulls that particular rabbit, no pun intended, out more the once in a long while. It’s also a rather brutal image for a series published for all ages. IDW’s announced that they intend to publish all the old issues in color, which would surely bump the rating of this scene a few age-groups. The important thing about the image is not if it is fitting for children, the important thing is that it works – because this is a story about death.

And when I write ‘this’ I mean both “The Fortress” in particular and Usagi Yojimbo as a general rule. Death defines the lives of these characters: it’s the most common end for most minor characters, and often the most desired one as well. When a lone ninja warrior sacrifices himself in the end of "The Dragon Bellow Conspiracy" storyline he does so while uttering the line “a… ninja’s duty… in life… is death!”

In Miyamoto Musashi’s Book of Five Rings, the other text they’ll insist you read if you want to know anything about samurai, the swordsman gives plenty of useful advice about how to fight, but he also allows time to drop this little spiritual bombshell: “Generally speaking, the way of the warrior is resolute acceptance of death.” Yamamoto Tsunetomo seemed to have agreed with this notion when he wrote - “Even if it seems certain that you will lose, retaliate. Neither wisdom nor technique has a place in this. A real man does not think of victory or defeat. He plunges recklessly towards an irrational death. By doing this, you will awaken from your dreams.”

All of this is well and good, but it puts Usagi in a bit of a spot. Because, as mentioned previously, he exists to the bind Umberto Eco describes. Usagi is both a figure of myth (the ultimate, idealized, samurai) and of romantic production (his adventures must be continually published). This means he can never die, but must continue to leave watching friends and family to perish without ever achieving his own ‘good death.’ There is a small meta-commentary about this issue, in a series that is otherwise remarkably straightforward, in the story “The Return of the Lord of the Owls", published in Usagi Yojimbo #135.

The titular character, a grim, undefeated, somewhat-supernatural specter of death that claims he’s able to see whenever an opponent ‘needs’ to die. He meets Usagi for the second time, his first appearance was more than a decade earlier in “The Lord of Owls” (issue #11). While everyone else who tries to challenge the Lord of Owls get a swift death Usagi, much to both warriors’ surprise, is allowed to live: “you are different from the others… but I cannot tell why.” Of course he is different – he’s the main character!

The only ‘end’ ever presented for the character and series is the elseworlds-esque Usagi Yojimbo: Senso limited series, which does give our rabbit his heroic ending – at the hands of Martian invaders. Usagi is so unkillable on his own terms that the only way Sakai thought he could die is by brining something so utterly outside the context of swords and demons. Even that story hedged its bets by turning that death into a story told by some distant successor (the cast of short lived spin-off Space Usagi); which means within his own world Usagi ascended into that realm of myth that Eco spoke of, becoming “immobilized in an emblematic and fixed nature.”

The new start Usagi Yojimbo embarks upon, new publisher, new number one, new colors, would probably turn out be much less important than one would expect. If the ideals are the samurai are something to aspire to while never being truly achievable so is Sakai’s continuing quest to create the perfect Usagi Yojimbo story – something that can never be done and yet, paradoxically, something he gets closer to every day.