Quincy’s energetic, juicy brush line and lively layouts showed that comic strip rendering could qualify as high art.

Quincy was created by Ted Shearer, who was born in May Pen, Jamaica in approximately 1919 and whose widowed mother had brought him to the United States when he was 19 months old. He grew up in Harlem during the storied Renaissance of the 1920s and 1930s. Shearer went to DeWitt Clinton High School, and at the tender age of 15 (or 16 or 17, accounts vary), he sold his first cartoon to the Amsterdam News.

Shearer credits famed E. Sims Campbell with setting him on the road to being a cartoonist. He’d seen Campbell’s cartoons in Esquire and in the Amsterdam News and “immediately became inspired.” And when he learned that Campbell lived in New York, he went to see him with a bundle of cartoons under his arm. He rang the doorbell, and Campbell’s wife appeared.

“A gorgeous woman, she was very gracious to me,” Shearer remembered for Jud Hurd’s magazine, Cartoonist PROfiles (No.11, September 1971). “She said she knew that he would see me—although he was a little busy at the moment—and she asked me to write him a note for an appointment. Then a week or so later, I got a card from him, telling me when to come. And this was the beginning of a beautiful relationship. He not only taught me some of the ins-and-outs of the cartoon business but gave me a number of things—knowing that my mother and I weren’t too well off. I recall a drawing light—and even a dog on one occasion!”

From 1938 to 1940, Shearer went to the Art Students League on a scholarship, and after World War II, he took courses at Pratt Institute. During WWII, he found himself in the Army, serving in the 92nd Division; called the Buffaloes, the 92nd was the only segregated division to see action in Europe. In off hours, Shearer drew cartoons about army life and sent them to Continental Features, which marketed them in the states.

According to Tim Jackson, author of the landmark book Pioneering Cartoonists of Color, Continental Features “was a syndicate created by an African American to distribute to the black press cartoons that featured characters of color, chiefly drawn by African American artists and illustrators.”

Shearer became an illustrator for Stars and Stripes and gained the rank of sergeant. According to St. Wikipedia, Shearer earned a Bronze Star for his work as art director for the 92nd Division’s magazine, The Buffalo.

Back home after the war, Shearer continued with Continental Features. He created three weekly single-panel cartoons: Around Harlem, about the social life of young black men and women in the early 1940s (which ran February 14, 1942 - March 11, 1944); and Next Door (August 12, 1942 - early 1948) and The Hills (roughly the same period), more family-oriented and focused on black families in a big city. All three appeared regularly in the Amsterdam News.

Shearer also freelanced illustration work and cartoons to newspapers and magazines. Before long, he was making the rounds of magazine cartoon editors’ offices in New York every Wednesday, “Look Day,” when cartoonists living in the area submitted their offerings in person. And he worked in animation for a while as an inbetweener. But when he first approached an advertising agency, he ran up against the kind of wall African Americans often ran into in those dismal days (and still do).

“When I gave my name over the phone in arranging for an appointment, I suppose they figured that ‘Shearer’ was Irish. But when I showed up for the meeting and the receptionist saw me, she went into an inner office and made me sit out in the reception room for an hour. When I finally did get in to see my man, he went through my portfolio in about three seconds and then said, ‘If there’s anything, we’ll let you know.’”

He had a similar adventure after he’d sent some cartoons to a religious magazine in Chicago. They didn’t use cartoons, they said, but they liked his drawings and asked him to illustrate a teenage question-and-answer page, one drawing a month. But before he got fairly started, he was invited to a get-acquainted evening being held in Manhattan for New York contributors.

“My wife and I worried over the big decision as to whether I should go to the function since I knew the magazine people weren’t aware that I was black,” he told Hurd. “I finally decided to go to the hotel that evening, and though the magazine people were very polite on the surface, I could easily tell from the subtle changes of expression on their faces that my being black had jolted them. As soon as they went back to Chicago, the picture changed: I was told that the teenage project was being phased out—although I’d been told previously that they planned to continue it for another year.”

It wasn’t “popular” then for any magazine to be using black talent. With Hurd, Shearer remembered when he sold his first cartoon to a mainstream magazine. “A gal at the Ladies Home Journal bought a drawing of mine. I will never forget that day—from that time on, I was so highly motivated that I could have accepted a thousand rejections in my stride. Then the humor editor of This Week bought something of mine, and I sold a little book to Friendship Press.”

Soon he was selling to Collier’s, Saturday Evening Post, and other magazines; and King Features often bought cartoons from him for its repertory gag cartoon Laff-a-Day, which featured different cartoonists in irregular rotation.

When Shearer approached Batten, Barton, Durstine and Osborne advertising agency, looking for assignments, his experience was “just the opposite” of what it had been at that other major ad agency. Shearer explained to Hurd: “I met a delightful guy, Larry Berger, who invited me into his office for a half-hour before he even looked at my things. You can imagine how much I appreciated his offering me a job a little later when I tell you of an experience I had just at that time. My wife and I had a couple of kids and we wanted to buy a house. When I went to the bank to talk to the loan manager, I almost fell off my seat when he looked at me and said, ‘We don’t issue loans to artists, writers, and tap dancers!’”

With experience in animation just as television was beginning to infect the daily lives of every American, demanding advertisements in motion, Shearer was hired as television art director, and he stayed with BBD&O for the next 15 years.

At the time he was hired, approximately mid-1950s, BBD&O was the most prestigious ad agency in the city. (Those of us pounding the pavement on Look Day at the time used to joke that “Batten, Barton, Durstine and Osborne” was the sound of a trunk tumbling down stairs; the famed investment firm of the day, “Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner and Beane,” was the sound of the trunk being dragged back up the stairs.) Shearer won five professional awards during his stay at BBD&O, and then in late 1969 or early 1970, he began conjuring up Quincy, prompted by a King Features artist, Bill Gilmartin, whom he often ran into on the commuter train to Manhattan.

Shearer submitted a succession of samples of the strip, and King bought it. Quincy was launched in 1970, maybe on June 13. In his entry in the membership album of the National Cartoonists Society, Shearer says the strip started in 1971, but that is mistaken: in the first paperback collection of Quincy, numerous strips dated 1970 appear. He also says Quincy began June 17, which is unlikely because that’s a Wednesday; June 13, a Saturday, may have been the date a character introductory strip appeared, but if so, the strip probably began its run on the following Monday, June 15.

Shearer left BBD&O almost at once.

He left because he was eager to fly solo. “I love to draw,” he told Hurd, “and I love the business of being an artist. But in advertising, no commercial or ad results from the effort of any one man. There are too many people involved for that to be possible. There’s the guy who comes up with a germ of an idea—the writer—the art director—the creative chief—the advertising manager for the client—the client—the client’s wife, and so on. On the other hand, in the case of Quincy, I feel a total responsibility for it six days a week.”

But he had loved the advertising business, too. “I’m one of the nuts who really enjoyed it. So many people knock it but I never found it hard to get up to go to work. Each day had a new bag of problems because we were always making new commercials. I loved the quickness of the guys involved in advertising—this really turned me on—and how I enjoyed the gassing sessions with them! In advertising, you’re always working with 3-5 other people, whereas I call the strip business ‘the loneliest job in town.’ I was never aware of this difference at BBD&O, and as I’m working on the strip, I sometimes wonder what the guys at the agency are doing at that moment.”

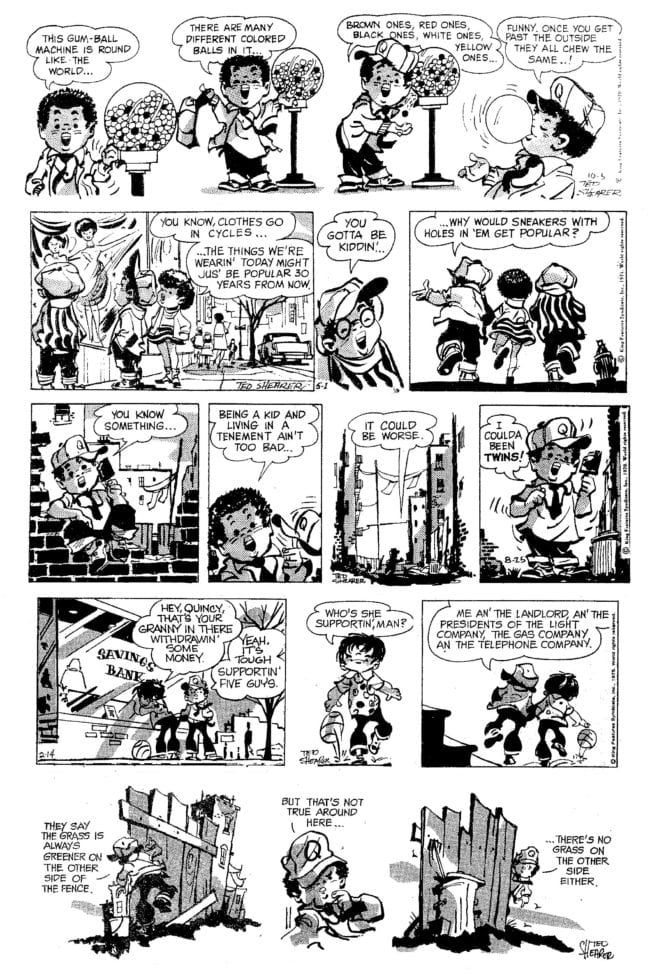

About Quincy, Don Markstein at his Toonopedia.com writes: “Most commentators on Quincy ... agree that Shearer's characters were identifiably minorities in lifestyle as well as skin tones, and often derived gags from the fact, but weren't vocal advocates of change. Mostly, they were just a bunch of kids who got along together and didn't give much thought to their racial identity." Quincy thrived, Markstein continues, “becoming one of a handful of the early integrated strips to survive beyond the 1970s.”

Said Shearer: “I’m sometimes tempted to do some preaching in the strip because I’ve been hurt so many times—being a so-called ‘black American’—but I always have to catch myself and realize I’m doing a humor strip and not an editorial strip.”

But it was also a question of tactics, Shearer explained to Hurd: “In the strip, I’m working with a nine- or ten-year-old black child, and no person wants a nine-year-old telling him what to do. It just doesn’t make sense.”

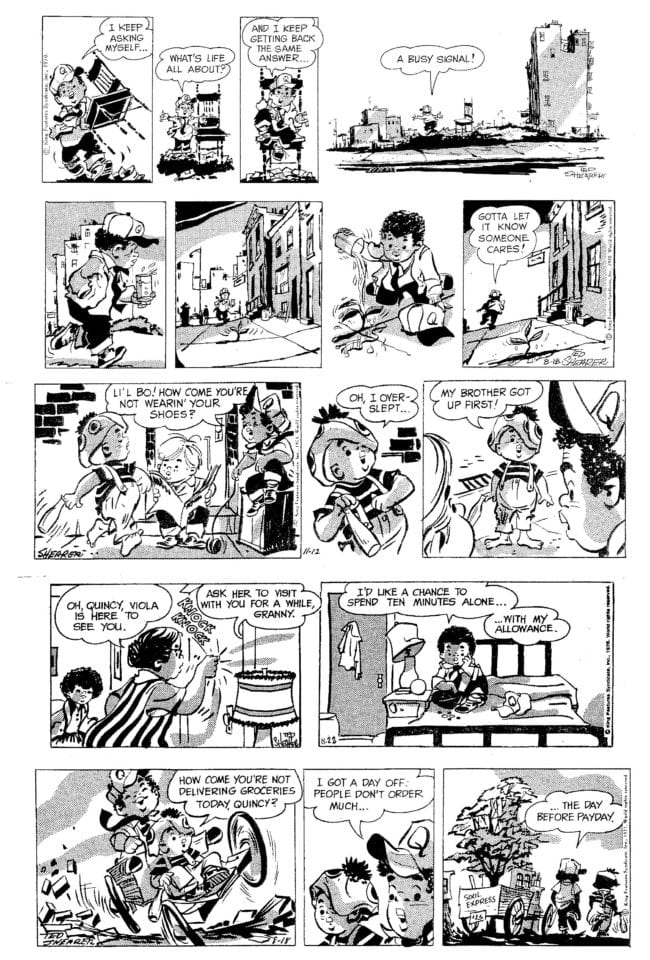

Quincy gets off a zinger every once in a while, but mostly, Shearer tried to make his case through more subtle means:

“I try to place this nine-year-old and the other characters in an environment in which readers can see the conditions under which these individuals live. By including authentic background drawings [of an inner city neighborhood], I’m making it possible for the reader to come to his own conclusions. I don’t want to turn readers off by becoming preachy. ... Quincy’s lecturing people would be the fastest way to stir things up. My first idea is to get people to like Quincy, to get them involved with the character, and then they can see for themselves the broken-down home, the torn sneakers, etc. Then perhaps readers will say, ‘Gee, maybe we can help.’ Or even the poor white can say, ‘Gee I went through this same thing myself.’”

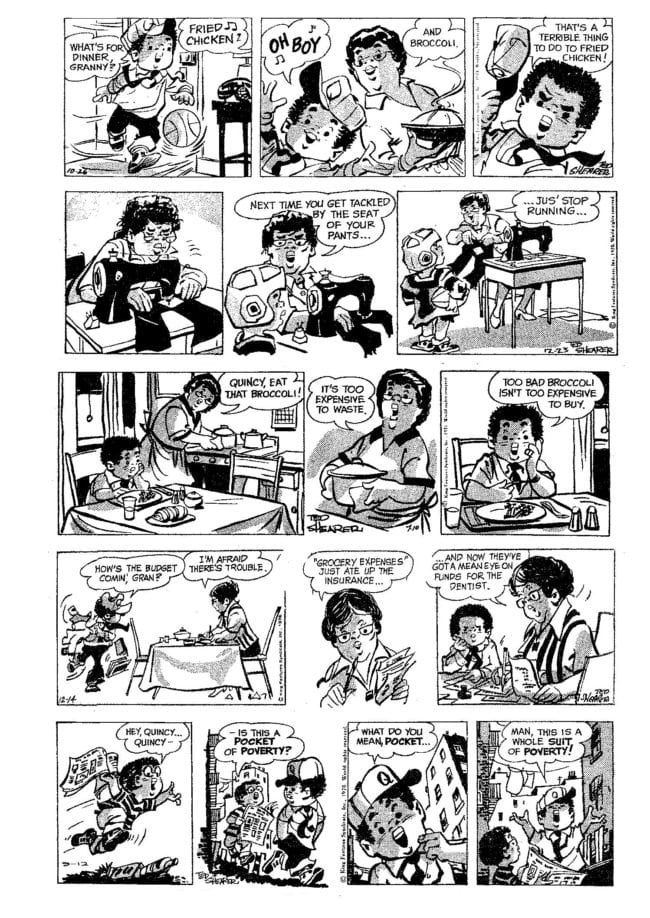

According to comics critic/historian Dennis Wepman in Ron Goulart’s Encyclopedia of American Comics: “Quincy and his buddies are natural, not particularly precocious children, neither mischievous nor sentimentally virtuous. They explore their environment and accept their problems with the serenity and resignation of little stoics, securely at peace in their slum. Quincy’s benevolent Granny Dixon, one of the few adults in the strip, exudes affection and support and provides a positive role model of discipline, love, and fatalism. Gracefully drawn, the realistic treatment of squalor in the crumbling tenements and cracked sidewalks of the backgrounds in Quincy is presented without rancor. Shearer rendered his characters sympathetically, without irony or indignation, and the social and economic problems that afflict them were cheerfully endured in an atmosphere of fellowship and fun.”

“The characters in Quincy were delightful,” wrote one unidentified web commentator, “ordinary children engaged in the everyday joys of young life in an inner city neighborhood. ... There was no wailing about their station in life, no complaining about their situations—just kids having good old kid fun.”

And occasionally taking a sharp poke at the residual discriminatory conventions of the outside society. If that sounds a trifle Pollyanna-ish these days, it was the essence of Shearer’s secret campaign to avoid rocking the boat of bigotry while at the same time drilling a few holes in the bottom in the hope that it would sink. Although the gags seemed authentic evocations of ghetto kids’ attitudes, they were often tepid. But the pictures never were.

In many of the strip’s daily installments, Quincy breaks the fourth wall and talks directly to the reader. This device shifts the typical verbal-visual balance of cartoon art, and the comedy becomes mostly verbal. Much of the Quincy comedy comes from the words even when the fourth wall isn’t broken. Ahhh, but the pictures are worth looking at whether they contribute directly to the joke or not.

Whatever the political or sociological impact of Quincy, the strip was undeniably one of the best drawn strips in the nation’s newspapers. Shearer’s liquid line waxed and waned and waltzed through the panels, a symphony of calligraphic variations that the cartoonist accented with artfully spotted black solids and painterly gray tones laid on like watercolor. (As, indeed, they were: when he finished inking a strip, Shearer splashed in a light blue wash to indicate where the syndicate art department should add Ben Day dots to create the gray tones.)

But there was more to Shearer’s artistry than drawing technique.

The kids in Quincy are always on the move: like kids everywhere, they talk as they walk or run or shoot hoops, and the talk usually has nothing to do with the actions being depicted. And no kid ever moves in the same way as the kid next to him: when Shearer drew three kids walking down the street, each kid has his own body English and perambulates in his own idiosyncratic fashion. That’s pure kid stuff, no question. But I think it came about for reasons arising from an artist’s compulsions not an anthropologist’s.

The words carry the joke, and, with the joke out of the way (so to speak), it is as if Shearer could then play with the pictures, and to keep himself interested, he introduces as much visual variation as he can conjure up in what’s left of the panel space after putting in the speech balloons. The result is not just aesthetically pleasing: it also authenticates the life Shearer was portraying by giving it constant, childish movement.

And the strip goes beyond mere authenticity in its pictures. Shearer varies panel composition when he doesn’t need to for the sake of the joke; he does it for the sake of visual interest, giving his readers something different to look at in every panel. He gives the dynamic of his pictures torque by shifting camera angle and distance from panel to panel. And the dynamic brings the pictures to life. Quincy and his grandmother and his friends live through the sheer artistic vitality of Shearer’s drawings. And the visual emphasis brings the balance back to the verbal-visual medium.

Cartoonist Mike Lynch performs insightful analysis of some Quincy strips at his blog; look for August 28, 2008 and February 27, 2009. Evidence of Shearer’s masterfully rendered comic strip is available these days in just two pocketbook collections: Quincy, from Bantam in 1972, and Quincy’s World, Tempo Books, c. 1978.

Shearer ceased Quincy with the release for October 4, 1986. I don't know why. He was 65 (or thereabouts: the year of his birth varies from one account to another), and in those days, people retired when they reached 65. Maybe that’s why he shut down the strip after just 16 years. But he continued to pursue a creative life, collaborating with his photojournalist son John in producing a series of children’s books about Billy Jo Jive, which spawned animated segments on Sesame Street and an animated feature, Billy Jo Jive Super Private Eye, produced by Shearer Visuals in 1979.

Shearer died December 26, 1992. Cardiac arrest, his son told the New York Times.

Brumsic Brandon Jr.’s strip about African American kids, Luther, which began in 1969, had expired in June the same year as Quincy. With continuity strips Dateline Danger (November 11, 1968 - March 17, 1974) and Friday Foster (January 18, 1970 - February 17, 1974) long gone, that left only Morrie Turner’s Wee Pals to represent African Americans in the funnies (February 15, 1965 until Turner’s death January 25, 2014). Surprisingly, perhaps, the dearth of diversity made editors of newspaper comics pages think seriously about how to remedy the blight.

It began, according to Dave Astor at Editor & Publisher, when in 1988 the Detroit City Youth Advisory Commission “urged Detroit newspaper editors to do something about the virtually all-white comics pages.”

Executives at the Detroit News and Detroit Free Press complained to syndicates about the lack of diversity. Cartoonists were urged to introduce characters of color into their mostly white casts.

Later that year, “coincidentally or not,” Astor wrote, “several talented African American cartoonists were offered syndicate contracts: Ray Billingsley, whose Curtis began in October 3, 1988; Robb Armstrong, whose Jump Start began the next year, as did Steve Bentley’s Herb and Jamaal.” And Barbara Brandon, daughter of Luther’s creator, launched her Where I’m Coming From, a weekly commentary cartoon with a black feminine point-of-view, in the Detroit Free Press in 1989.

All these strips and features are well-drawn. Not a sloppy job anywhere in sight. Anatomy is drawn, not abstracted; no stick figures anywhere. Line work is confident. But the artwork in Ted Shearer’s Quincy is in a class by itself—the class above first class.