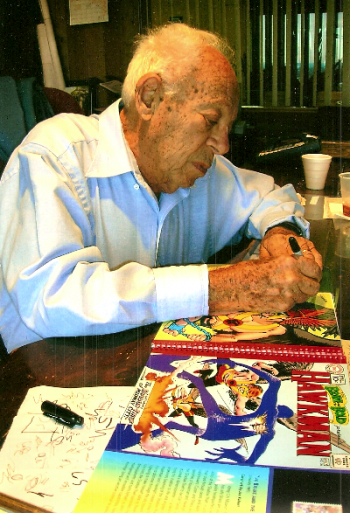

Although he’s not a household word to most comics fans, Sheldon Moldoff worked on or was associated with some of the most famous characters in comics history, including Batman, Hawkman and Hawkgirl, Superman, and the Green Lantern. Although he retired to Florida in 2000, he was still appearing at conventions selling his drawings right up until a 2009 Comic-Con International appearance. This was remarkable because Moldoff had been there at the very dawn of the superhero age, working as Bob Kane’s first assistant on Batman in Detective Comics. While working with Kane in the late 30s, and then again in the 50s and 60s, Moldoff is credited with co-creating the following characters: Batman supervillains Poison Ivy, Mr. Freeze, Matt Hagen (Clayface), the playful inter-dimensional Bat-Mite, as well as the original Bat-Girl (Betty Kane), and Batman’s canine sidekick, Ace the Bat Hound. Moldoff’s stiff, funky style dominated the Batman strip for more than a decade in which the Caped Crusader battled hordes of aliens and other strange creatures. A modest, hard-working professional, who had come up during the Great Depression, Moldoff seemed grateful to be working at all, and never signed his work as a ghost. Because of this, he labored in anonymity for the bulk of his career, until he was rediscovered by fandom in the mid-70s through regular convention appearances where he would sell his watercolors of Hawkman, Batman and other characters. Although he drew the first cover featuring The Green Lantern (All-American #16), and was a prolific cover artist, Moldoff’s most widely seen work is probably the fourteen years of Batman covers and stories he ghosted for Bob Kane (1953-1967). He was let go by DC in 1967, along with other Golden Agers like Wayne Boring, when DC decided to update the look of strips like Batman and Superman.

Although he’s not a household word to most comics fans, Sheldon Moldoff worked on or was associated with some of the most famous characters in comics history, including Batman, Hawkman and Hawkgirl, Superman, and the Green Lantern. Although he retired to Florida in 2000, he was still appearing at conventions selling his drawings right up until a 2009 Comic-Con International appearance. This was remarkable because Moldoff had been there at the very dawn of the superhero age, working as Bob Kane’s first assistant on Batman in Detective Comics. While working with Kane in the late 30s, and then again in the 50s and 60s, Moldoff is credited with co-creating the following characters: Batman supervillains Poison Ivy, Mr. Freeze, Matt Hagen (Clayface), the playful inter-dimensional Bat-Mite, as well as the original Bat-Girl (Betty Kane), and Batman’s canine sidekick, Ace the Bat Hound. Moldoff’s stiff, funky style dominated the Batman strip for more than a decade in which the Caped Crusader battled hordes of aliens and other strange creatures. A modest, hard-working professional, who had come up during the Great Depression, Moldoff seemed grateful to be working at all, and never signed his work as a ghost. Because of this, he labored in anonymity for the bulk of his career, until he was rediscovered by fandom in the mid-70s through regular convention appearances where he would sell his watercolors of Hawkman, Batman and other characters. Although he drew the first cover featuring The Green Lantern (All-American #16), and was a prolific cover artist, Moldoff’s most widely seen work is probably the fourteen years of Batman covers and stories he ghosted for Bob Kane (1953-1967). He was let go by DC in 1967, along with other Golden Agers like Wayne Boring, when DC decided to update the look of strips like Batman and Superman.

In addition to his comics work, Moldoff also wrote and storyboarded 65 episodes of Courageous Cat and Minute Mouse on behalf of Bob Kane for television syndication. These five-minute episodes originally aired from 1960-62. As usual when working for Bob Kane, Moldoff was given no credit by his parsimonious employer. Moldoff described his relationship with Kane in an interview conducted in the late 90’s, “It was not in his personality to give credit to anybody. And it didn’t bother me as much as it bothered (Batman writer) Bill (Finger) because I accepted it, and I went into it with an open mind. He said just don’t say anything, and...all we had in those fifteen years was a handshake, that’s all.” However, Moldoff felt vindicated in 1991 when longtime D.C. editor Julius Schwartz praised Moldoff’s work on Batman, saying: “All those years I was buying artwork from Bob Kane, I was buying it from Shelly Moldoff.”

In addition to his comics work, Moldoff also wrote and storyboarded 65 episodes of Courageous Cat and Minute Mouse on behalf of Bob Kane for television syndication. These five-minute episodes originally aired from 1960-62. As usual when working for Bob Kane, Moldoff was given no credit by his parsimonious employer. Moldoff described his relationship with Kane in an interview conducted in the late 90’s, “It was not in his personality to give credit to anybody. And it didn’t bother me as much as it bothered (Batman writer) Bill (Finger) because I accepted it, and I went into it with an open mind. He said just don’t say anything, and...all we had in those fifteen years was a handshake, that’s all.” However, Moldoff felt vindicated in 1991 when longtime D.C. editor Julius Schwartz praised Moldoff’s work on Batman, saying: “All those years I was buying artwork from Bob Kane, I was buying it from Shelly Moldoff.”

Moldoff also worked on the theatrical animated film, Marco Polo, Jr. which was released in 1972, for which he received writing, storyboarding, and producing credits. Among his many, many other professional credits, Moldoff created “The Black Pirate” strip for DC, he also drew Hawkgirl’s first appearance in costume, though the design was by original Hawkman artist Dennis Neville, the artist that Moldoff replaced. Moldoff did not create the Hawkman character as some comics histories have erroneously stated. Hawkman was created by writer Gardner Fox and Dennis Neville. He also drew E.C.’s Moon Girl comic in the late 40s for E.C. Comics founder M.C. “Max” Gaines. In the 60s, he put out the Bob’s Big Boy title and other giveaway comics for the Shoney’s restaurant chains for over a decade.

Moldoff also claimed to have been the person who gave Bill Gaines the idea to do horror comics in the late 40s, packaging the first issue of an E.C. horror comic that included “Zombie Terror”, widely credited as the first published E.C. horror story. Moldoff claimed that Gaines simply swiped the idea without compensating him. If so, that was a first for the eccentric, but generally open-handed Gaines. He also said that Gaines’s lawyer Dave Alterbaum threatened to blackball him in the comics industry if he talked about how his idea had been stolen. When questioned about this incident years later, Al Feldstein, who wrote and edited all of the E.C. horror comics except for Vault of Horror, could not confirm Moldoff’s account of the origins of E.C. horror comics, and Bill Gaines has been dead for years, so whether it is true or not, will probably be lost to history, though Moldoff retained records of the work he offered to Gaines, which seem to bear his story out. Fortunately, Moldoff was able to sell his idea to Fawcett, which published This Magazine is Haunted, and Strange Suspense Stories, based on Moldoff’s titles and concepts.

Moldoff also claimed to have been the person who gave Bill Gaines the idea to do horror comics in the late 40s, packaging the first issue of an E.C. horror comic that included “Zombie Terror”, widely credited as the first published E.C. horror story. Moldoff claimed that Gaines simply swiped the idea without compensating him. If so, that was a first for the eccentric, but generally open-handed Gaines. He also said that Gaines’s lawyer Dave Alterbaum threatened to blackball him in the comics industry if he talked about how his idea had been stolen. When questioned about this incident years later, Al Feldstein, who wrote and edited all of the E.C. horror comics except for Vault of Horror, could not confirm Moldoff’s account of the origins of E.C. horror comics, and Bill Gaines has been dead for years, so whether it is true or not, will probably be lost to history, though Moldoff retained records of the work he offered to Gaines, which seem to bear his story out. Fortunately, Moldoff was able to sell his idea to Fawcett, which published This Magazine is Haunted, and Strange Suspense Stories, based on Moldoff’s titles and concepts.

Born in New York City, Moldoff grew up in the Bronx and had the good fortune to live in the same apartment building with early comics great Bernard Bailey. “As far back as I can remember, I loved cartoons…” Moldoff recalled in 1995 interview. Bailey observed the young Moldoff drawing cartoon characters like Betty Boop and Popeye on the sidewalk in front of the building and offered to give him drawing lessons. By the time he was 17, Moldoff was selling his cartooning work to pioneering comics editor Vincent Sullivan, the editor of National Periodicals, one of the companies that eventually merged to form DC Comics (the others were Detective Comics, Inc. and All-American Comics, helmed by “Max” Gaines). Moldoff’s first sale was a sports filler page that appeared on the inside back cover of the first issue of Action Comics featuring the first Superman story. Although he started out doing filler pages for Sullivan in a “big-foot” cartooning style, Moldoff soon graduated to doing more realistically-drawn fare like Hawkman, Cliff Cornwall (an unmemorable strip about an aviator turned spy) and the Black Pirate, frequently swiping from artists like Hal Foster and Alex Raymond, which added to the visual flair of all three strips.

Born in New York City, Moldoff grew up in the Bronx and had the good fortune to live in the same apartment building with early comics great Bernard Bailey. “As far back as I can remember, I loved cartoons…” Moldoff recalled in 1995 interview. Bailey observed the young Moldoff drawing cartoon characters like Betty Boop and Popeye on the sidewalk in front of the building and offered to give him drawing lessons. By the time he was 17, Moldoff was selling his cartooning work to pioneering comics editor Vincent Sullivan, the editor of National Periodicals, one of the companies that eventually merged to form DC Comics (the others were Detective Comics, Inc. and All-American Comics, helmed by “Max” Gaines). Moldoff’s first sale was a sports filler page that appeared on the inside back cover of the first issue of Action Comics featuring the first Superman story. Although he started out doing filler pages for Sullivan in a “big-foot” cartooning style, Moldoff soon graduated to doing more realistically-drawn fare like Hawkman, Cliff Cornwall (an unmemorable strip about an aviator turned spy) and the Black Pirate, frequently swiping from artists like Hal Foster and Alex Raymond, which added to the visual flair of all three strips.

Moldoff drew Hawkman and the Black Pirate until he was drafted into the Army in 1944. While in the service, he worked on animated films for the Signal Corps alongside such notables as famed New Yorker cartoonist Charles Addams and Warner animation director Charles McKimson. When he returned to civilian life in 1946, he expected to take up where he had left off, but editor Sheldon Mayer (with whom he’d had a falling-out), refused to give him any work, so Moldoff turned his talents to Standard Comics, Fawcett, and Marvel. A few years later he received a phone call from Max Gaines and began working for him again, drawing special projects for Gaines’ Educational Comics, as well as such strips as “Madelon”, “Choo-Choo Jones”, and “Moon Girl and the Prince.” Moldoff continued on the Moon Girl strip for a brief time after Bill Gaines took over EC following his father’s death. Gaines and his new editor Al Feldstein soon inaugurated their justly-celebrated “New Trend” with titles like The Vault of Horror, Weird Science and so on, and once more Moldoff was out looking for work. Even though he caught a number of bad breaks throughout his career, Moldoff liked to say that he never went a day without work, even at times when other cartoonists were literally starving.

Moldoff drew Hawkman and the Black Pirate until he was drafted into the Army in 1944. While in the service, he worked on animated films for the Signal Corps alongside such notables as famed New Yorker cartoonist Charles Addams and Warner animation director Charles McKimson. When he returned to civilian life in 1946, he expected to take up where he had left off, but editor Sheldon Mayer (with whom he’d had a falling-out), refused to give him any work, so Moldoff turned his talents to Standard Comics, Fawcett, and Marvel. A few years later he received a phone call from Max Gaines and began working for him again, drawing special projects for Gaines’ Educational Comics, as well as such strips as “Madelon”, “Choo-Choo Jones”, and “Moon Girl and the Prince.” Moldoff continued on the Moon Girl strip for a brief time after Bill Gaines took over EC following his father’s death. Gaines and his new editor Al Feldstein soon inaugurated their justly-celebrated “New Trend” with titles like The Vault of Horror, Weird Science and so on, and once more Moldoff was out looking for work. Even though he caught a number of bad breaks throughout his career, Moldoff liked to say that he never went a day without work, even at times when other cartoonists were literally starving.

By all accounts, Moldoff’s retirement was a happy one. He sold a considerable number of his superhero watercolors and basked in the adulation of Golden Age comics fans. In 2000, he did his last work for his old publisher, DC Comics, in the World’s Funniest one-shot. He continued making convention appearances throughout the 2000s even though he was on dialysis and confined to a wheelchair. However, the indomitable Moldoff had been scheduled to appear at Mega-Con in Florida, but he was paralyzed by a stroke in December of 2011 and his health continued to decline until his death on March 6th.

By all accounts, Moldoff’s retirement was a happy one. He sold a considerable number of his superhero watercolors and basked in the adulation of Golden Age comics fans. In 2000, he did his last work for his old publisher, DC Comics, in the World’s Funniest one-shot. He continued making convention appearances throughout the 2000s even though he was on dialysis and confined to a wheelchair. However, the indomitable Moldoff had been scheduled to appear at Mega-Con in Florida, but he was paralyzed by a stroke in December of 2011 and his health continued to decline until his death on March 6th.

Sheldon Moldoff is survived by his daughter Ellen Moldoff Stein, his sons Richard and Kenneth Moldoff and by seven grandchildren and great-grandchildren.