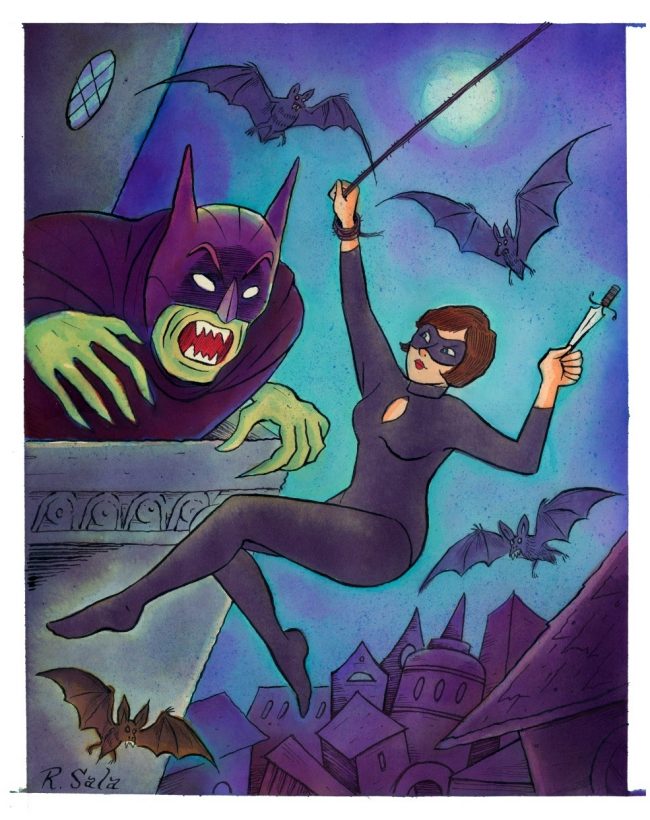

Richard Sala, whose tongue-in-cheek mystery/thriller comics — including The Chuckling Whatsit, Cat Burglar Black and Evil Eye — were like nothing else and everything else in popular culture, was found dead in his Berkeley, California, home last week. Sala was 65. No cause of death was announced and no information was available as to how long Sala had been dead before his body was discovered. His last Tumblr post was April 29: the beginning of a new serialized webcomic called Carlotta Havoc Versus Everybody. The webcomic had been announced on an Apr. 18 post at Sala’s blog, called Here Lies Richard Sala.

Readers always knew from the first panel of a Richard Sala comic that they were about to be taken for a ride full of shocking twists and turns, familiar genre set-pieces, matter-of-fact melodrama and dark-humored camp. His comics are as simple and iconographically propulsive as a 1940s Saturday-morning adventure serial or pulp magazine of the 1930s, but with the symbolic depth and labyrinthine dream logic of a Hitchcock or Bunuel film. They are above all the work of a fan, one of us, who learned to absorb the pop-cultural images that those of us of a certain age loved and use them to wallpaper hidden chambers of our shared unconscious. They are fun, funny, even exhilarating, but also full of glimpses into something darker that is never resolved and never entirely goes away. The fiendish masterminds are forever escaping.

Stylistically and thematically, Sala’s work suggests elements of other artists, but remains unique. It’s easy to recognize in his comics the shadowy gothic black humor of Edward Gorey or Charles Addams or even Charles Burns — like Gahan Wilson, but with sharper angles. But his art is also perfectly distinct, impossible to confuse with the look of any other cartoonist. The reader follows a trail of connections in Sala’s stories, and ultimately those connections point to the multitude of influences that make up the boomer generation’s (sometimes second-hand) youth.

A partial list of Sala’s acknowledged influences includes Nancy Drew book covers, Jorge Luis Borges, Dick Tracy (his favorite comic strip), Franz Kafka (his favorite author), Fritz Lang and German Expressionism, James Bond (the paperbacks and the Sean Connery movies), Derek Flint, Matt Helm, Grimms’ Fairy Tales (which he would often read before going to bed, the better to conceive new story premises), Jack Kirby’s Demon, Atlas comics, Heavy Metal, Lynd Ward, Jack Cole, Esquire cartoonist Miguel Covarrubias, Donald Barthelme, Barry Yourgrau, Russian writers Gogol, Daniil Kharms and Alexei Remizov, The Avengers (his favorite TV show), The Prisoner (his other favorite TV show), The Man from U.N.C.L.E., The Girl from U.N.C.L.E., The Wild Wild West, The Shadow and Doc Savage paperbacks, Italian pop-pulp film Danger: Diabolik, old Sherlock Holmes movies, Famous Monsters of Filmland magazine, Castle of Frankenstein magazine, Japanese woodblock artist Utamaru, Matt Groening, Lang’s Doctor Mabuse movies, Dario Argento, Drew Friedman, Edgar Wallace, The President’s Analyst, The Tenth Victim, the 1967 Casino Royale, Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu novels, The Abominable Dr. Phibes, Mario Bava’s Blood and Black Lace, Joseph Heller’s Catch-22, George Grosz, Kurt Vonnegut, Richard Brautigan, J.D. Salinger, Aldous Huxley, David Goodis, Kenneth Fearing, Jonathan Latimer, Harry Stephen Keeler (Google him), Fredric Brown, Joel Townsley Rogers’ The Red Right Hand, G.K. Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday, the films of Hitchcock, Sam Fuller and Joseph H. Lewis, Georges Franju’s Judex and Eyes Without a Face, Louis Feuillade’s Fantômas serial, Mark Beyer’s Dead Stories, …

In a 1998 interview for TCJ #208, Sala told Darcy Sullivan, “I’d set my alarm for three in the morning, get up, and watch Stranger on the Third Floor, Somewhere in the Night, Fallen Angel, or Phantom Lady. And then I would go back to sleep, and when I got up it was almost like it was a dream. That’s the way I saw movies I liked since I was a kid, staying up past my bedtime to watch Atom-Age Vampire or Weird Woman or I Walked with a Zombie.”

Sala was born in Oakland, California, in 1955. His mother was a student at the University of California – Berkeley and came from a moneyed WASP background when she met his father, a first-generation Sicilian with an 8th-grade education, working as a janitor at the school. Both were collectors, his father eventually becoming an antiques dealer and proprietor of a clock shop, which made an appearance in Sala’s comics. Sala was a middle child, with a brother who was two years older and a sister who was three years younger. When Sala was 3, the family moved to Chicago so his father could take a job at a company owned by his mother’s father. In Chicago, the young Sala became entranced by museums — their mummies, skeletons and dioramas.

But Sala suffered from asthma, and in 1966, the family moved again to the healthier dry air of Scottsdale, Arizona. Sala, victimized by bullying classmates, felt himself an outsider in Arizona, and when he discovered Kafka in high school, he recognized an instant kinship. Things were no better at home. In a 2006 interview conducted by Logan Kauffman on the Adventures Underground website, Sala stopped short of using the word “abusive,” but described his father, who had been a lumberjack and a member of a motorcycle gang, as “angry and irrational and would often terrorize me, my brother and my sister with violence or threats of violence. … Nevertheless, my father is where I get almost all of my creative side from.”

Sala’s father could draw and shared with his son a love of old monster movies. Sala told Darcy Sullivan, “I see now, looking back, that my whole interest in the irrationality of violence stems from this childhood.”

Sala’s parents divorced when he was 14, and father and son eventually became permanently estranged. Possibly to a more than average degree, Sala was raised by popular culture. He cut out Dick Tracy and Li’l Abner strips and kept them in scrapbooks. He also kept notebooks in which he wrote down the plots and titles of TV shows like The Avengers. He even took Instamatic photos of the TV screen during these shows and captured the audio on a reel-to-reel tape recorder. He ordered frequently from the Captain Company ads at the back of Warren magazines.

Sala started at Arizona State University with a major in English, not art, and his ambition was to be a writer. He sent stories to science-fiction pulp magazines of the time, but his gothic obsessions were a peculiar fit with SF genre expectations and his submissions were invariably rejected. His art and comics, however did appear in ASU’s State Press and the local weekly New Times.

In college, Sala began to engage with his pop-culture pleasures in a more analytical way as he read scholarly articles about comics and horror movies like Eyes Without a Face. “I became fascinated with meaning and subtext,” he told Kauffman, “but I also couldn’t deny the visceral thrills either.”

Sala married psychology student Terry Doyle, a union that lasted 20 years, the two remaining close even after their divorce. He left ASU and pursued an art major at Mills College in Oakland, California. After graduating in 1982 with an MFA in Painting, Sala took a job as an assistant librarian at a private college. The shadowy rows of shelves full of old knowledge and tales were a comfortable environment for him, the kind of place where rendezvous are kept and discoveries made. The library was famous for its parapsychology section with impressive collections of books on hypnotism, vampires and the occult.

But Sala found the library to be a little too comfortable. Later, in therapy, Sala identified this period and the decision he made as a turning point. He could either get the library-science degree necessary to devote himself to the academic-library field or he could take a chance on becoming a full-time artist. Noting that the many doppelgangers in his stories suggest that his psyche was split in two, Sala told Sullivan that this moment in his life represented a tug-of-war between parental influences: the maternal womb of the library versus art’s risk of frustration, failure and self-destruction, which had consumed his father. “I’ve always felt a struggle with duality, between two sides of myself. For example, how do I reconcile the side that loves fine art and literature with the side that loves lurid pulp fiction and comic books?”

In this case, Sala obeyed his internalized father and left his library job to work as an artist, self-publishing his first comic book, Night Drive, in 1984. Night Drive was more concerned with art and genre abstractions than with narrative (more the fine-art Sala than the pulp-fiction Sala), but against all odds, it caught the attention of Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly, who ran Sala’s work in the last issue of the seminal art comic Raw in 1986. MTV’s Liquid Television, which was culling talent from Raw, picked up Sala to do a serialized, animated version of “Invisible Hands” from Night Drive. The six two-minute chapters ran on Liquid Television’s first season in 1991.

Sala quickly became ubiquitous in the burgeoning alternative-comics scene, appearing in the first four issues of Fantagraphics’ Prime Cuts anthology series in 1987 and in Drawn & Quarterly, beginning with its second issue (1990). He produced anthology titles for Kitchen Sink Press (Hypnotic Tales — 1992, Black Cat Crossing —1993) and for Dark Horse (Thirteen O’Clock — 1992). His work appeared in pretty much every small-press alternative-comics anthology, beginning with a three-page story called “Strange Question” in Escape #9 in 1986 and including contributions to Snarf, Buzz, Twist, Street Music, Rip-Off Comix, Taboo, and Deadline USA (which originally serialized the chapters collected in Thirteen O’Clock).

Sala’s first color work was seen in Drawn & Quarterly, but the printing in those issues did not live up to his expectations. He had better luck with Monte Beauchamp’s Blab! which regularly ran color stories by Sala in the late 1980s and mid-1990s.

Sala had the kind of style that editors remembered. They knew what they would get when they invited Sala to contribute. Sala was happy to be identified with this style and didn’t think highly of the ability to shift between different styles. “I felt that a ‘style’ was simply who you were,” he told Kauffman “— you shouldn't be able to (or want to) completely change your ‘style.’. It's not honest. You should be able to look at an artist's work and immediately know who it is — it should be unique, like a fingerprint.”

Sala had one style, but it was style that different people could experience in different ways. Strangely enough, his Wikipedia entry identifies him as primarily a creator of “children’s fiction.” And in fact he did contribute a series of Merlin the Magnificent strips to the Nickelodeon kids’ magazine from 1993 to 1995. Children’s author “Lemony Snicket” collaborated with Sala on a piece for the Little Lit children’s anthology. The child-friendly look of his art may have been due to his clean line work, but in his own comics, those clean, cartoony lines were used to tell stories punctuated by sudden death, violence and menace.

The first full realization of the kind of story Sala wanted to tell may have been The Chuckling Whatsit, which Fantagraphics’ Kim Thompson agreed to serialize through 17 issues of the anthology title Zero Zero from 1995 to 1997. Sala described The Chuckling Whatsit as the beginning of a new period in his work. “I envisioned it as a process of peeling the layers from an onion, or slowing peeling off mask after mask, getting closer to the truth,” he told Sullivan. “I wrote Chuckling Whatsit as a thriller. But it ended up telling me a lot more about my own unconscious than I had prepared myself for.”

Sala’s protagonists primarily functioned as a point of entry for readers, like a seat on a roller-coaster. Ex-detective Charms in Sala’s In a Glass Grotesquely described the experience of being a guiding point of view in a Sala serial: “It’s like this: I’m seeing patterns in seemingly unrelated crimes. I’ve kept notes connecting supposedly random events. I can almost make out a shadowy hand … of someone behind it all, an intelligence. A … a … a puppetmaster.”

The hold that these themes had on Sala hints at the motivations that kept Sala drawing comic books despite the fact that he could have made a much more lucrative living by focusing exclusively on illustration work. As his reputation grew, Sala was in much demand as a magazine and newspaper illustrator and he did work for Newsweek, Entertainment Weekly, Business Week, Playboy, Esquire, The New York Times, Seventeen, The Washington Post and many more. He also did 70 illustrations for a Jack Kerouac screenplay called Dr. Sax and the Great World Snake and illustrated two CD-ROMs for avant-garde rock band The Residents.

But Sala always came back to comics, turning out titles that were variations on a set of themes, like Peculia in 2002; Maniac Killer Strikes Again in 2004; Peculia and the Goon Grove Vampires in 2005; the 200-page Mad Night in 2005, originally serialized in Evil Eye in 2003; a collaboration with Steve Niles in IDW’s Little Book of Horror in 2005, The Grave Robber’s Daughter in 2006; Delphine, which was serialized over four issues from 2006 to 2009 and collected in 2012: Cat Burglar Black in 2009; The Hidden in 2011; Violenzia in 2013; In a Glass Grotesquely (featuring a deadly mastermind who has been driven mad by despair over the state of the world) in 2014; and The Bloody Cardinal in 2017. His most recent works, including The Bloody Cardinal, have been serialized on Tumblr, a venue even less lucrative than comics.

“Like a lot of cartoonists, I’m not really doing comics for money. I’m doing them for myself …” he told Sullivan. “There was some unconscious turmoil going on, and somehow my stories were exorcisms for me. Certainly I want people to bring their own experience to the stories and enjoy them, the way I relate to Kafka, for example. At the same time, they’re little psychic snapshots of my psychological state at that moment. … These were motifs I was using as personal symbolism for my own life.”

It was not a life that Sala expected to be long. “I never thought I would make it to 30,” he told Sullivan. He had had suicidal thoughts at an early age, during his darker days in Arizona, but the reason he couldn’t see past 30, at least at that time, was that he couldn’t imagine himself as old. Despite his sometimes scary childhood, he was heavily invested in his youth — the half that was all imagination, the Captain Company artifacts, the iconography, the cultural imagery. Nothing allowed him to return to that imaginary space so much as drawing comics.

“I’ve really fallen in love with the process and the form of comics,” he told Sullivan. “I really feel honored to be part of the tradition.”

Richard is survived by his sister, Lucy Sala.