I had gotten the impression that, after Jaakko Pallasvuo's English-language debut Some Approaching End was published in 2011 by Landfill Editions, the artist had abandoned comics to focus on net art. A piece then appeared in Mould Map 2, a text story about browsing the Facebook pictures of an object of fascination. It was easy to view this as a transitional piece: It appeared in a comics anthology, but was not a comic, and it took as its subject the internet's increasingly primary place in the world, maybe to the detriment of the human, in a way that seemed to cry out to be addressed and worked through further. In the way it only incidentally used that book's incredibly striking color palette, as a series of overlapping textures to frame a plain-speaking direct address, it paralleled Blaise Larmee's piece in the same anthology, in which an author stand-in spoke of wanting to quit comics for art, where the critical context would appreciate him more.

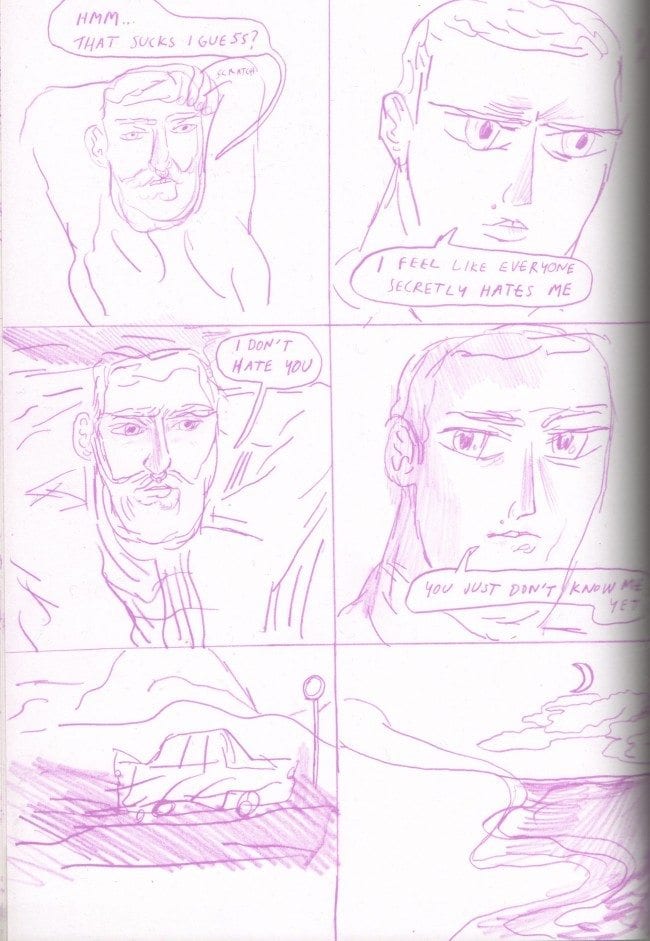

That Pallasvuo has, a few years later, made another long-form comic comes as something of a surprise. Reading it, I retain the impression he might be disinterested in, or at best ambivalent towards, making comics now. The drawings are much looser than they were, and seem more perfunctory than anything: Often there are drawings of characters' faces, their designs seemingly not premeditated in the slightest -- the main character's appearance separates itself from the idea of "just draw a face" with a single mole above the lip -- while a few squiggles serve as a background. The storytelling often defers to close-ups of these faces, with the only background being wavy lines. There is pretty much no compositional flair or sense of the figures inside of a particular space: The visual vocabulary employed here is that of a student filmmaker whose skill set is able to handle little beyond a documentary's talking heads. While Pallasvuo once labored over page layouts, here he sticks to a strict six-panel grid, with the occasional splash of a blurry cityscape for contrast. It seems like he is trying to work quickly and speak directly, as the narrative itself implicitly appears to be an answer to the question, "Why don't you make comics anymore?"

There comes a moment when an artist can no longer be considered young. The feeling of possibility, that anything can happen in their life, comes to coexist with a sense of potential not being fulfilled. This is felt with every passing moment, or, in the case of Pure Shores, each new scene. Every scene takes place in some kind of liminal state: Whether it be a dream sequence, or the initial moments after waking, or the first meeting between one character and another who has yet to be introduced. On first reading, each page feels improvisatory. There is no real way to tell where the story is going, because there are deliberate signals that point in one direction only to go nowhere. The story is set in 2027, but the narrator mentions that "Gatsby's throwing this NYE party," giving the impression of a Fitzgerald novel set a century later. This creates certain expectations for a scene where characters take a ride in a self-driving car that then go unfulfilled. The storytelling feels restless, and it is this quality that seems to drive the book into existence, moreso than any desire to tell a specific story. What is captured is the self-loathing of an artist unsure of himself and the work he makes, questioning whether any of it holds meaning. The exercise of the book is driven by an interrogation of its characters, which in turn interrogates the artist himself.

Pallasvuo's personal circumstance, choosing between two forms that each offer little prospect of financial reward, differs considerably from those of his main character, who has found great success as a Young Adult novelist through cultivated pandering to already existing cultural trends. The protagonist's self-examination has led to self-loathing. As he pursues relationships, any romantic swoon suggested by the softness of Pallasvuo's pencil drawing, printed in pink, or the surface similarities shared with shojo manga stylings, are betrayed by the pacing of the six-panel grid, the staple of American action comics since the days of Jack Kirby. There is something "punk rock" about the insistent tempo of the book, suggesting aggression as a background noise, that then calls attention to the way the characters offer sarcasm quickly, the way they warn people they are meeting for the first time that they will hate them once they get to know them. The sketchiness of the drawings does not communicate the feelings the characters are having in any moment, but rather their own ambivalence towards those feelings, and their place in the narrative of their lives. Self-loathing has corrupted everything, and any tender emotion the characters might wish to feel for each other is obscured behind several levels of irony and knee-jerk hostility.

One page is spent on recreating the final dialogue exchange in Stanley Kubrick's Eyes Wide Shut, taking Kubrick's apparent thesis about the basis for a healthy relationship—fucking— and playing it as a come-on offered sarcastically. In the context of the rest of the book, this quotation-as-detournement seems to place the entirety of Kubrick's oeuvre as this post-World War II Baby Boom second-half-of-the-twentieth century cultural moment, of coupledom, and childrearing. A child of the 1990s, growing up under parents who attempted to instill in them the importance of "self-esteem," placing a premium on talk of following dreams that would allow and encourage someone to become an artist, now exists as a liberal in a modern moment where they must ask themselves, "Am I problematic?" If Eyes Wide Shut was about the upper middle class of 1999 existing on the periphery of the wealthy's decadence, in the near future where the middle class no longer exists, playing at nihilistic decadence as a member of the nouveau riche is the least the characters can do to pretend to ignore their own guilt.

The answer to the question "why did you quit comics?" is "because fuck comics." The bulk of the narratives offered are the same as those found in Young Adult fiction, and this then colonizes the dreams and aspirations of the young, luring them away from meaningful activist work. If their dreams convince them to be an artist, then these are a silly and unserious dreams, which will leave them unsatisfied even in the statistically unlikely chance that they're able to achieve them. The readership comics can reach consists only of the comfortable and complacent and more comics will only make them more so. The glory of the form for its own sake can be better interrogated by other people, whether it be Frank Santoro, whose Pompeii this book most resembles, or Aidan Koch (who Pallasvuo used to collaborative with through the mail, back when she was drawing in pencil). This comic exists to document looking into the mirror on one's thirtieth birthday, knowing that to break the mirror in a fit of rage will not do anything close to inventing Cubism, but still feeling the urge to do something that will register your disgust.