Originally published in The Comics Journal 261, 2004.

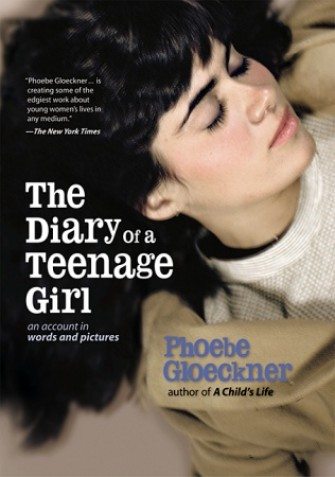

Phoebe Gloeckner has certainly come into her own of late. She has published more work in the last few years than she had in the previous 20. A Child’s Life (1998) collects much of her comics work from 1976 to 1998. The Diary of a Teenage Girl (2002) is her quasi-fictional (she would say entirely fictional) diary of a teenage girl, part prose, part comics.

Phoebe Gloeckner has certainly come into her own of late. She has published more work in the last few years than she had in the previous 20. A Child’s Life (1998) collects much of her comics work from 1976 to 1998. The Diary of a Teenage Girl (2002) is her quasi-fictional (she would say entirely fictional) diary of a teenage girl, part prose, part comics.

Gloeckner does not consider herself a cartoonist so much as an artist, for whom cartooning is one of the modes in which she works. She is also a prose writer, a painter, an illustrator, a web designer, fummetist, and, most recently, a college professor (though that is likely not an art), has even dabbled in what I would call student/experimental films. She also, notoriously if not artistically, combines photographs into a National Inquirer-like verisimilitude, and humiliates publishers. For all I know, she also plays the trombone.

She has been drawing comics since 1976 (at the age of 16), and was most influenced early on by the underground commix anthology Twisted Sisters, especially the work of Aline Kominsky-Crumb and Diane Noomin, and Robert Crumb (not a twisted sister), all of whom became good friends. Their influence runs deep: Gloeckner’s work is predominantly autobiographical and scaldingly honest. Unlike theirs, her work is less “cartoony” and more representational, and her depiction of life is unflinching and intense.

Gloeckner’s work appeared in a variety of underground or alternative anthologies throughout the '80s and '90s — Young Lust, Wimmen’s Comix, Weirdo, and others. Perhaps because she is not prolific (A Child’s Life collects every major piece she’s done since 1976), she has for too long flown under the radar of all but the most hard-core comics aficionados. I’ve admired her work since I first discovered it (sometime in the late ‘70s or early ‘80s) and have threatened to interview her for a decade now. I’m not sure why it’s taken me this long, but I’m glad it did since I was able to discuss what I consider to be a major work that came out in late 2002 — The Diary of a Teenage Girl.

Gloeckner is prickly about the autobiographical nature of her work and I enjoyed teasing out of her complex (and sometimes antagonistic, obdurate, and polemical) protestations about the label. I’ve known Phoebe for a dozen or so years now (or so it seems) and she’s as intense, funny, reflective, and confrontational as her work, and I enjoyed every minute of it. We’ll have to do it again soon. -Gary Groth

Postscript, 2011: It’s curious that in all of my off-the-record conversations, including casual dinners, I never exchanged an adversarial word with Phoebe, who I dearly love both as an artist and a friend. I must’ve been in serious take-no-prisoners interview mode when I conducted this considering how relentlessly I badgered her about how autobiography is used in her “fiction.” Although it’s a little painful to read, it’s also exhilarating and I manage to crowbar some interesting observations out of her and, besides, artists should probably be badgered, hectored, and browbeaten much more than they are these days — when they are more likely to be feted, cow-towed and deferred to, and generally held in awe by rapturous toadies and gawkers and groupies. Fortunately, Phoebe is one of the most revealing cartoonists alive and not in an exhibitionistic, but in a self-exploratory, way, and her conversation is similarly self-explanatory — without guile or at least conscious guile. I only wish she were more productive, only because I love her work and the more sagacious art in the world the better, but that’s like wishing for less war or smarter politicians — something beyond our control. We should be happy that she’s done as much as she has.

The Phoebe Gloeckner Interview

A Child’s Life

GARY GROTH: You were born in 1959, in Pennsylvania.

PHOEBE GLOECKNER: I was born in 1960, in Philadelphia.

GROTH: OK … and even though you’re an intensely autobiographical artist, which you don’t like to admit, there are these huge holes in your biography. So, I want to fill them. You were born in Pennsylvania and you were raised in Quaker schools. You didn’t move to San Francisco until you were 12. There’s very little about what life was like in Pennsylvania that I could find. First of all, tell me the circumstances in which you went to Quaker schools as opposed to a regular US public school. Is there a distinction between a Quaker school and a public school?

GLOECKNER: In Philadelphia or anywhere?

GROTH: In Pennsylvania, I guess.

GLOECKNER: Well, I can only speak about Philadelphia in particular, because that’s where I went to school as a young child.

GROTH: I sort of had the impression that you might have been living in a rural area, but perhaps that’s only because I don’t think of Quaker schools in an urban setting.

GLOECKNER: No. Quaker schools are like parochial schools. I mean, they’re not public; they’re private, and there are certainly quite a few of them in the city of Philadelphia. I suspect you’re confusing Quaker (also known as the Society of Friends) with Amish or Mennonite, which would be more rural. I went to them because my parents divorced when I was pretty young and my dad was an artist, and he didn’t work, really. So, he didn’t pay child support. His parents did. They were Quakers, and they paid for us to go to Quaker schools in Philadelphia.

GROTH: So, your grandparents were Quakers, but you were not, and your mother was not. So your mother just acquiesced to your father’s parents wanting you to go to Quaker school?

GLOECKNER: Well, acquiescence is not the word. I think she was glad. I mean, Quaker schools are great schools generally, and the religious aspect is gentle and not at all overwhelming, and even though we, as students, did go to Quaker meetings once a week, it was not an unpleasant experience — I don’t know if you’ve ever been to one, have you?

GROTH: No, never.

GLOECKNER: There’s no intermediary between you and God, OK? So, there’s no directed service so to speak. It’s a silent meeting — a meditative atmosphere, a simple, unadorned setting. After a time of silence, people are permitted to stand up and express their thoughts and generally it’s something inspirational. Or meant to be. It’s also very soothing. I mean, you’re supposed to just sit there and be silent. Sometimes, nobody speaks.

GROTH: Did you like this? Did you take to it?

GLOECKNER: Well, yeah, I liked it. But I was never a very calm child so it was hard to sit for that long.

GROTH: But did you find that it gave you some sort of equilibrium in your life that …

GLOECKNER: I remember it positively. I don’t know if it gave me equilibrium …

GROTH: You didn’t pursue it.

GLOECKNER: You mean in my adult life?

GROTH: In your later adolescence — you moved from Pennsylvania when you were 12, and you certainly didn’t take it with you from what I can gather.

GLOECKNER: Actually, when I went to San Francisco, I did go to a Quaker meeting there. I didn’t like it at all, because in San Francisco they’re kind of divorced from the traditional historical Quaker meeting. It was more … San Francisco is so progressive and alternative, it was like hippies had taken it over, kind of like “God’s eyes.” Totally different; lots of veterans and stuff. It was a different thing. The Quaker schools that I went to in Philadelphia, there were graveyards associated with them, and I was very morbid and I loved to hang out in the graveyards during recess and look at all the gravestones. There was none of that in San Francisco. It was just like a converted flat. A Quaker meeting was in an old building …

GROTH: Insufficient ambiance …

GLOECKNER: Right. Too many hippies, and I think at an early age I developed a kind of allergy to hippies. Actually, this was in the ’60s, and most of my teachers in these Quaker schools were all hippies, too.

GROTH: Now, your parents divorced when you were four, and you’ve described your father as an artist, and you said he was influenced by Mad. What kind of an artist was he? Was he a commercial artist, or did he try to be a fine artist?

GLOECKNER: Well, he tried to do both. I think he initially wanted to be a fine artist, but to tell you the truth, I don’t know. He was kind of like me in a way. He was all over the map trying different things.

GROTH: What of his work do you remember, or have you seen?

GLOECKNER: He was great with pen and ink. I remember watching him draw. He could draw just as well as anybody I know. His paintings were really beautiful — at least his early paintings. Later on, he took a lot of drugs, and started taking a lot of speed and his drawings became obsessive and overly detailed and lost a sense of gestalt. It was just all detail. He was one of these artists who was so distracted by life that he never really settled down enough to create a cohesive body of work.

GROTH: They divorced when you were pretty young. How traumatizing was that? Do you remember much of that?

GLOECKNER: Yeah, I remember it. I don’t know if it was a trauma … Divorce is not an instantaneous thing. It’s a gradual progression, and if you’re four years old, you don’t remember the papers. I remember that their relationship wasn’t good. I remember them fighting a lot.

GROTH: What was their relationship like after they divorced? Was he around?

GLOECKNER: No. I saw him maybe once a year, and it always strange because in order to compensate for seeing us so rarely, he would buy us the biggest and the best and the most Christmas presents, or the weirdest Christmas presents. So I always remembered when I saw him. When I was about 7 years old, he bought me a Styrofoam cutter, and a whole bunch of Styrofoam, scrap Styrofoam, huge bags of it. If you’ve ever had a Styrofoam cutter, you know it’s really a simple thing, a red-hot wire stretched vertically between a base and an adjustable horizontal support … but it was a weird present to give a seven-year-old. I remember the smell of it, just sitting there, watching and guiding the Styrofoam as the wire cut through it like butter. It was really fun to do that. Hypnotic. I burned myself a few times, and my Mom got really mad, and then I didn’t see my Dad for a while. And then one year he gave me… I had said I wanted some reptiles or something, and he gave me a big aquarium, not with one or two lizards, but 40 or 50 tiny, overcrowded lizards. I think they were anoles. They’re smooth and green and very quick. I remember trying to get one of them out of the cage so I could play with it. I lifted the lid but a lizard bit me, and I dropped the lid and they all escaped, and I remember for months after that finding dried up lizard carcasses under the sofa, in the toy chest, or we’d find the cat chewing on one in the corner.

GROTH: You said that he inspired your interest in art, but you also said you were afraid of becoming like him.

GLOECKNER: Well, yeah, everyone always told me I was just like him, since I was born.

GROTH: By that do you mean self-destructive?

GLOECKNER: See, that’s the thing. Most people were just referring to the fact that I could draw well when I was a little kid and so could he. I think that’s mostly what they were talking about. However, there were a lot of other things … I mean, he was destroying himself from a really young age, from before I was born. That scared me because I knew it, I always knew it. I was kind of waiting for him to die since I was little.

GROTH: You actually felt that?

GLOECKNER: Yeah, I mean, he was the funniest person, the most charming person, everybody loved to be around him, but you could just see it — he was burning the candle at both ends. My grandfather was a German immigrant. He came over here and he became a rag picker at a printing company in Philadelphia and he worked his way up until he owned the company. It was a large company and I loved to visit it. There were huge web presses running 24 hours a day. He made a lot of money. Then my grandmother was the vice president of the AMA, the first woman doctor with such a position, so they were both quite successful. My dad was really talented, but he was the youngest kid, and a total goof-off. But he was their baby, and they indulged his every whim. He never held a real job. Whenever he was in trouble, they’d give him money. They just threw money at him and it probably didn’t help him, really. He always had these crazy schemes. For example, he really liked fast cars, so he tried to start this Shelby Mustang business where he sold vintage parts and put cars together and did this and that, and …

GROTH: He was good with cars.

GLOECKNER: Yeah, but he kept stuff all over the place, unfinished. I guess one thing I remember that he actually finished was a project he started with an old Jaguar. He took the engine out and he put a V-8 engine from a pizza truck into it and had to remodel the hood because the engine was so big. He made some money betting on his cars in quarter-mile races. Sometimes he drove the cars. He loved speed — the drug and the high-velocity. Anyway, my grandfather financed all this stuff, but nothing really got done. My dad and some teenage boys who worked for him would mostly sit around and smoke pot and drink beer … these kids ended up stealing car parts from under his nose. Eventually, everything was gone, or ruined.

GROTH: Wasn’t a girl killed in a car accident he had when he was 16 years old?

GLOECKNER: Yeah. That’s right. I guess if that hadn’t happened, I wouldn’t have been born, because she was the girlfriend that was his best girlfriend …

GROTH: Oh, that he would have married if he hadn’t married your mother.

GLOECKNER: Yeah. He met my mom right after that and he had an accident with her. She still has a big scar on her face from it. But he killed this other girl.

GROTH: She was in the car with him or she was in the car he hit?

GLOECKNER: They were together, on a date. She was 16. I guess he was 16, too. He was drunk and he was going too fast. My grandfather bailed him out somehow and — my aunt tells me that my grandfather paid a mechanic to say there was a mechanical failure. I don’t know if that’s the truth or not … ’cause everyone’s dead. My father told me about the accident himself, when I was 13 or 14, visiting him for a week in the summer.

GROTH: Where did he live?

GLOECKNER: He lived in New Jersey at that time. I lived in California. But, like I said, he was always taking speed and so he liked to stay up until 4 in the morning, and he liked company. So, I remember so many times just sitting there, because I wanted him to like me. I’d do whatever he wanted. I’d stay up and just talk to him; we would draw and we’d play music and his wife would get really fucking pissed off that we were staying up so late.

GROTH: Why, since he stayed up anyway?

GLOECKNER: Well, it’s not like she wanted him to stay up all night and sleep all day… I don’t blame her for being angry and unhappy. He really just sat around, smoked cigarettes and talked all the time.

GROTH: Not an exemplary husband.

GLOECKNER: Nah. Didn’t fit the role, but I guess he was trying. Anyway, one of these nights, in the middle of the night, he tells me about this girl. I must have been about thirteen, and it made a huge impression on me. “This is my dad and he killed this girl. I wouldn’t have been born if she hadn’t been killed. Someone else might have occupied this space in life …” It’s frightening to think that your parent has caused the death of someone, and I didn’t see him as innocently killing her. I knew that he must have been drinking. He drove recklessly with my sister and me, too — he liked to drag race, and he would drive as fast as he fucking could in the middle of the night on these back roads in the Pine Barrens of New Jersey. He’d be going well over whatever, like 120 miles per hour or something, just to show off how fast he could go.

GROTH: With you in the car?

GLOECKNER: Yeah, with us!

GROTH: Jesus.

GLOECKNER: He always said, “Don’t tell your mom.”

GROTH: So, how did you feel about that? He was clearly risking your life.

GLOECKNER: Scared … but I didn’t see him very often, so, you know, when you don’t see your dad much you want to make a good impression, and part of that is trying to please him by doing whatever it is he wants to do. So, I just tried to go with it. Closed my eyes and felt the wind streaming over my face. I figured, “He’s our Dad, he doesn’t want us to die, he knows what he’s doing.”

GROTH: So do you have a theory as to what these demons were that he was wrestling with?

GLOECKNER: I don’t really know. I honestly don’t know. I could guess — my grandparents were so straight and so success oriented, and they were probably always pushing him.

He was a wrestler in high school, and he was really good, but they were always pushing, just pushing, pushing, pushing everybody. They wanted me to be a doctor. I don’t think he even wanted to wrestle professionally.

GROTH: So, what kind of art did he do? What were his paintings like? What were his drawings like?

GLOECKNER: I think his best paintings were his early paintings, when he drew old barns and rooftops. He liked to draw decaying buildings, and they were good paintings, but later on, like I said, he kind of got on this tweaking speed drawing thing. You could see he had talent and skill, but it looked like something that came out of the mind of someone who’s speeding.

GROTH: But he inspired you to draw?

GLOECKNER: I think I had it in me to draw anyway, so it wasn’t just him, but I definitely identified with him.

Artistic Beginnings

GROTH: How young were you when you started drawing?

GLOECKNER: Well, all kids draw.

GROTH: Yeah, but some kids are more obsessed with it than others.

GLOECKNER: I guess I was obsessed with it early — so early that I don’t remember.

GROTH: And did you draw continually? Or did you have your periods of …

GLOECKNER: No. I mean, I pretty much did something all the time. I was always writing or drawing or making newspapers …

GROTH: So, what was life like in Pennsylvania? Your father was gone after age four …

GLOECKNER: My mom remarried, but we were really pretty poor for a while. At first, we lived in a converted garage belonging to a painter friend of hers, Napoleon Gorsky. My mom was young. When I was four, I guess she was barely twenty and she had 2 kids and she was going to college. My mom’s parents took care of us much of the time. We moved around a lot. I don’t think I lived anywhere for more than a year before I was a teenager, and I went to a different school every year. I didn’t make lasting friends. I made temporary friends, that I would remember forever, but I wouldn’t keep in contact with them because I was a little kid, you know?

GROTH: Did that bother you as a kid, or did you just consider it normal?

GLOECKNER: It felt normal to me, but it was also painful. I was always in a state of missing someone, and then you go to a different school and everybody already has friends and so you kind of feel left out, and then you end up becoming that kid on the outside over and over and over again. I guess you get used to that. That probably carries over. It probably affected my personality somehow.

GROTH: Were you close to your sister?

GLOECKNER: No. She’s two years younger than me. We fought like crazy. I was so mean to her. I tried to kill her.

GROTH: Really?

GLOECKNER: Yeah.

GROTH: Was it just because she irritated you, or because there was something in you that you would have had to …

GLOECKNER: Because she was my sister, I guess. I was a really angry little kid, and it was also that they told my mom that I was borderline hyperactive, they wanted to treat me with drugs if they could. I was like a problem kid.

GROTH: What was the man that your mother married like?

GLOECKNER: You mean, after my Dad? He was a Pygmalion, 10 or 15 years older than my mother. He was Scottish. A professor of calculus or something at the University of Pennsylvania, and then he became a publisher.

GROTH: Uh oh!

GLOECKNER: I know. [Laughs.] I mean, he was an editor, and then he moved up through the ranks … you know, as an editor of scientific books, and then he got hired as Editor in Chief of Scientific American, which was at that time based in San Francisco. So that’s why we moved to San Francisco.

GROTH: I see. So he was pretty accomplished.

GLOECKNER: Well, he was very smart, but very fucked up.

GROTH: How was he fucked up?

GLOECKNER: He was an angry person.

GROTH: How did this manifest itself?

GLOECKNER: Well, sometimes he’d get mad at our cat and chase it around the house with a broom, eventually catching up to it and bringing the broom down on the animal’s head with all his strength. [Laughter.] On the other hand, he was the one who found the cat run over in the snow. He carried it home, dead, with tears streaming down his face …

He was very conflicted. He called his parents “peasants” because they hadn’t gone to college, but he had put himself through the University of Edinburgh and got his PhD in the States and had made something of himself. An intellectual. But he remained conscious of his “peasant” roots … He had a great disdain for people he saw as “nouveau riche,” probably because he was nouveau everything, having come from a poor family. He was critical of ignorance, and admired intelligence, and had a cruel habit of comparing people: who was smarter, who was more beautiful, who was more this or that.

GROTH: It sounds oppressive. How long were they married?

GLOECKNER: They were married for 10 years, but separated for half of the time. It wasn’t very stable.

GROTH: Was there anything positive about his involvement in the family, or his …

GLOECKNER: Oh sure. For me it was great because he thought I was bright, and he let me know this. But on the other hand, he had a natural daughter and he would tell me that I was brighter than she was. So this is an example of him comparing people, and in this case I was put in a position of feeling like I had betrayed someone—my stepsister.

GROTH: More guilt.

GLOECKNER: More guilt. Right.

GROTH: Now, when you were a kid, you were not particularly drawn to comics from what I can tell.

GLOECKNER: No, not particularly … I read Little Lotta and Little Dot sometimes.

GROTH: So the drawing you did when you were a kid, it wasn’t cartoony; it wasn’t related to comics; it wasn’t stories; it was just individual illustrations.

GLOECKNER: Right. I guess. Drawings. I drew people …

GROTH: I understand you moved to San Francisco when you were 12. That would have been around 1971, I guess.

GLOECKNER: Seventy-two.

GROTH: You said that your parents had underground comics around the house at that time. Who would your parents have been at that point?

GLOECKNER: That was the stepfather I was just talking about and my mom.

GROTH: The professor of calculus?

GLOECKNER: Yeah. Right, professor of calculus.

GROTH: So, you sneaked looks at the underground comics?

GLOECKNER: Yeah, that’s what they had. They had all the dirty ones.

GROTH: Well, they were all dirty, weren’t they?

GLOECKNER: Yeah, I guess they were.

GROTH: So, do you remember which comics were lying around? I know that Twisted Sisters was a huge influence.

GLOECKNER: Yes, a huge influence, but that came out later.

GROTH: So, what other comics?

GLOECKNER: Well, the first ones I saw were Zaps. And, you know … Wonder Warthog …

GROTH: Was this a revelation to you?

GLOECKNER: Yeah, because I think that’s how I found out about sex. I remember just feeling incredulous and shocked, and I think it switched something on in my head. The revelation was, OK, well, you can write a story about anything in comics.

GROTH: How old would you have been when you discovered underground comics?

GLOECKNER: About 12.

GROTH: Crumb’s “Joe Blow” had a big effect on you.

GLOECKNER: Yeah, it did. I loved the drawings, how soft they looked and rounded …

GROTH: Tactile …

GLOECKNER: Yeah … they reminded me of Garth Williams. I loved Charlotte’s Web, and other E.B. White stuff he illustrated, but that story, “Joe Blow,” it’s like you can just pick it up off the page. It’s very … dimensional somehow, and for a kid, it’s very appealing. It looks like a kid’s book illustration. Stuff like Victor Moscoso, I’d look at it, but it just was like prickly daggers, sharp and slick. It wasn’t attractive to me.

GROTH: Too abstract?

GLOECKNER: No, too clean and not warm. The images didn’t mean anything to me either. I don’t know.

GROTH: What about Wilson? He’s pretty warm.

GLOECKNER: Oh yeah, I liked Wilson a lot. What … Ruby and the Pirates? Star-Eyed Stella … but still that never seemed to be about real people. I mean, Crumb was talking about real people. Then when I saw Twisted Sisters. Aline was writing directly about herself, and Diane Noomin had the character, Didi Glitz. Do you know that comic?

GROTH: Of course, yeah.

GLOECKNER: It’s the best. I still think it’s better than any later Twisted Sisters.

GROTH: Right, and Didi Glitz was an alter-ego of Diane’s.

GLOECKNER: Yeah, exactly, and it was the funniest thing I’d ever seen. Still, if I look at that, I just laugh out loud. Unfortunately, she’s hardly ever recognized for how wonderful her work is. You look on lists of comic books and comics creators and she’s rarely included. I think she’s one of the best. Seriously. I love her stuff.

GROTH: She’s great, but she’s not prolific. I mean, she does comics very sporadically.

GLOECKNER: This wasn’t always true. It certainly didn’t matter to me whether she was prolific or not. I just read whatever she did.

GROTH: Yeah, we should do a collection of all of her work.

GLOECKNER: Yeah, it’s a good idea. Do it.

GROTH: There are a million projects in the back of my head that we have to get around to, and that’s one of them. So this had an enormous effect on you at the age of 13 or 14?

GLOECKNER: Yeah.

From San Francisco to Prague

GROTH: Now what happened when you hit San Francisco? It seemed to me like your life changed radically.

GLOECKNER: Yeah, my parents divorced almost immediately.

GROTH: Your mother was obviously still very young. She’s only, what, 18 years older than you, or something?

GLOECKNER: Or less. Seventeen, maybe. Yeah, so she was barely 30.

GROTH: So, how do you characterize what happened to you when you hit San Francisco? You really went berserk.

GLOECKNER: It wasn’t so simple. For one thing, I was on the brink of becoming a teenager when we moved, so it probably would have been a difficult time anywhere. But … when I lived in Philadelphia, my mom wasn’t the only one taking care of us. We stayed with my grandparents 2 or 3 days, at least, out of any given week. Then we move 3000 miles away, my mother immediately got divorced, and there was no support system for us — no friends, no grandparents. My mother was, like you said, still quite young and pretty good-looking and freshly divorced. I suppose not everyone is too young to be a parent at 17, but my mother was. At the time we’re discussing, she was ready to make up for lost time and join the big coke and disco party that was going on in San Francisco in the 1970s.

GROTH: Partying?

GLOECKNER: Yes! Partying like someone who has kids probably shouldn’t be. I’m not being judgmental, or I’m trying not to be, except that I have kids and, you know, you kind of have to be a bit subdued. Or channel your energy into something other than nightclubbing. Anyway, when we were in Philadelphia, it was fine because we stayed at my grandparent’s house two or three nights a week, at least.

GROTH: So your mother would just go out and party …

GLOECKNER: Yeah! When we moved to San Francisco, she got divorced and she became wild maybe because there wasn’t the constraint of having her parents around. My grandparents had been a very stable and loving influence, and in San Francisco we were just three females alone and my sister and I were kids. It was in a way very exciting but in a way, very bleak.

GROTH: But that allowed you to have a certain anarchic latitude in your own life.

GLOECKNER: Yes, but I’m not sure I would have chosen anarchy if I’d been given the choice. Deep down, I seek order. What I did with this “latitude” was often fueled by anger or despair … but when you’re a kid you don’t realize what’s motivating you.

GROTH: Your work is autobiographical …

GLOECKNER: I know I’ve said this in a million interviews, but I really think that every artist is writing about their own life experience. And so…

GROTH: You perhaps more so than most.

GLOECKNER: — and perhaps not. You make a character of yourself, and in that sense it’s no longer you. It’s like a doll you’re moving around and putting in little diorama. I’m not making a documentary, because if you tell the story of your life, no one’s going to read it because it’s boring. You have to put stuff into narrative form that’s accessible to people, and in doing that you’re totally transforming it into something else.

GROTH: True, but most of your work is about you and your experiences and your interpretation of them. But they’re not about invented characters.

GLOECKNER: Well, a lot of times there are invented characters.

GROTH: Well, the main characters don’t seem to be. I mean, maybe peripherally, but you and your mother, your step-father, Tabitha, these are all characters that are real and who you knew.

One of the few stories you wrote and drew that was not about you was an evening in Prague, and I’m not sure if that was about characters that were real people you met in Prague — it looked like it.

GLOECKNER: Those characters are based on people that I knew.

GROTH: So, most of your work seems to be an attempt to understand your own experience very directly.

GLOECKNER: Right, but I guess … It is, but it’s not important to me that it is me or isn’t me. It could be anyone. It’s not that I want people to understand me; I want people to understand … Well, you know, it’s hard to speak about artistic motivation, but …

GROTH: I wanted to ask you a little about the year you spent in Czechoslovakia. Can you give me a context for that? How old were you and what year was this?

GLOECKNER: It was 1980 and I was newly married, foolishly, to this nice Jewish punk-rocker. I say foolishly, because at the time, marriage meant very little to me. I didn’t really want to get married. You know, I was 19, and it seemed like a joke. But he really wanted to get married. I said, “OK, if it means so much to you, but, I’m telling you the truth: It means nothing to me.” I think I justified it as a sort of punk statement- I was going along with the establishment in order to dilute its power.

GROTH: Was he older?

GLOECKNER: He was about six years older. He had already gone to college; I hadn’t gone to college yet. We had a big Jewish wedding. His parents had wanted me to convert to Judaism, but it seemed wrong to me, since I was more of an agnostic than anything else. Anyway, at some point we broke up and I fell madly in love with this Czech boy, 19 or 20 like me. I was at San Francisco State, and one of our teachers threw an end-of-the-semester party at her studio, and this guy comes up to me and says, [putting on an accent and deep manly voice], “ I hear that you are married. I think that’s really stupid.” [Laughter.] I found that incredibly charming.

GROTH: So, you were beguiled immediately by this opening line.

GLOECKNER: Right. I was.

GROTH: And by the accent.

GLOECKNER: And by the accent. I mean, I didn’t even know where Czechoslovakia was, not exactly. My neighbor, Frank, a crazy-smart veteran with a collection of bazookas had to drag out his huge altas of the world to show me where Prague was. Which is kind of funny because I’d always been very interested in communists. In sixth grade I bought myself a subscription to Soviet Life, because I had the idea that “If people would only learn more about the communists, they’d realize they’re just like us! We’re all human beings!” So, I’d show my Soviet Life to everyone, like my Grandparents, and try to engage them with the concept. Anyway, I was very receptive to this Czech person, Jakub Kalousek. He’s a great artist. I had never seen someone work on his art in such a selfishly and selflessly focused manner. As it happened, I had already signed up to go for a year to France in the International Program at San Francisco State. When I was in France, I went to visit Jakub’s parents in Czechoslovakia, which was very interesting. At that time it was like 1983, I guess, and it was still very, very communist with nothing else on the horizon for years. I had to go to the police station every single day to get my passport stamped.

GROTH: Every day.

GLOECKNER: Every day. I was the only American for miles around. Finally, I met one other American, and it wasn’t a tourist. It was Gene Deitch, Kim Deitch’s dad. Jakub’s father, Jiri Kalousek, was a fairly well-known animator and painter who had worked on projects for Barandov Studios, where Deitch’s wife, Zdenka, was director of animation, I believe. Gene Deitch is an animator as well. So Kim Deitch’s father and Jakub’s father had many common acquaintances. It’s very small world, and it was kind of cool and fun to be learning this at the age of 23. Then I went back later and went to school there for six months or something, and then stayed longer.

GROTH: In Czechoslovakia?

GLOECKNER: Yeah.

GROTH: So why did you want to go to school there?

GLOECKNER: Because I loved it.

GROTH: Notwithstanding the oppressive communist regime?

GLOECKNER: No. I really like learning languages, and love the Czech language. I love the culture, and… I just loved the feeling of being in another country. It was a very exciting time to be in Prague- particularly as a young American, going to a place where very few Americans had gone. Most of my life, I would have done anything to go anywhere. I had a great wanderlust. When you have kids, as I do now, it’s a little harder.

There was a period of several years where I was going there pretty often. Later on, I did an internship in medical illustration in Paris, and then I went back to Czechoslovakia after that for a while.

GROTH: How did you earn money there?

GLOECKNER: In Prague? Well, if I had a dollar, it was worth about 30 dollars on the black market.

GROTH: That helps.

GLOECKNER: It would have, however, I didn’t feel comfortable increasing my wealth in this way. I would exchange dollars for crowns with friends at the official exchange rate, which was much less favorable to me, but still I felt like a thief because everything was so cheap. I didn’t even need money, basically. I was living off student loans from the States. And besides that, I stayed with Jakub’s family, and I had to force them to let me pay for anything.

GROTH: What about your internship in Paris in medical illustration? When did this happen and what was that like?

GLOECKNER: It was ’86 or ’87. The internship was disappointing. I went expecting and hoping for some very rigorous, challenging work, but my “mentor” was more interested in flirting and taking long lunches. It was a valuable experience, however, from the standpoint that I was able to observe surgery in France. I attended various plastic surgery procedures, including many liposuctions, performed by one of the surgeons who had originated the technique.

I saw surgeries in Czechoslovakia too. When people found out I was an American studying medical illustration, I got invitations from several doctors to observe their work. It was fantastic, and a great privilege for me- just because I was American — even though I was only 23 or 24 — I had the respect due a distinguished diplomat. I was treated with a respect I surely didn’t deserve, but I loved every minute of it.

GROTH: Liposuction is where they suck out fat, right? With a tube? Like a vacuum cleaner?

GLOECKNER: Yes, it’s interesting. It can be a major procedure. I saw a full-body liposuction, where there’s a danger of major blood loss… it’s hideous… there were large jars of orange, blood-tinged fat being filled and moved aside, one after the other, like the canopic jars the Egyptians used for organs…. [Laughter.] Afterwards, the patient’s body must remain tightly bond, like a mummy, so that the skin will re-size itself to the new dimensions of the body in a predictable (hopefully) manner.

GROTH: Not pretty.

GLOECKNER: No…

GROTH: Well, that’s in keeping with a theme that runs through your work, which is that the body is never divorced from metaphysical issues. Is that true? Is that how you feel?

GLOECKNER: I guess so, yeah. I’m not at all Catholic, and I mean this in terms of the Catholic hierarchy of the soul and then the body. My experience of being alive is that body and soul are inseparable.

GROTH: Are you religious now?

GLOECKNER: No.

GROTH: Are you agnostic or atheist? How would you describe yourself?

GLOECKNER: I guess it would be agnostic. Although I have said atheist. Call me agnostic. Because I kind of believe in ghosts, but I guess that’s not really believing in God.

GROTH: No, I think there’s a difference there.

GLOECKNER: But it’s very spiritual.

GROTH: Ghosts are?

GLOECKNER: Yeah. Aren’t they? They’re spirits.

GROTH: I suppose they could be. Wait, let me back up: When you say you believe in ghosts, are you being serious?

GLOECKNER: Well, sort of.

GROTH: In what sense?

GLOECKNER: Well, see, I have this aunt, Aunt Jane, who I’ve always loved and respected more than nearly anyone else in my family. She is a genealogist, and she spent so much time in graveyards just looking for people’s names… When I was a kid, she would tell me she saw ghosts, and I wanted to believe her so badly. And the fact is, I don’t really believe her, but I still want to believe her.

GROTH: Sure.

GLOECKNER: So, there’s part of me that wishes very badly to believe in ghosts.

GROTH: Badly enough to believe in them.

GLOECKNER: Right.

GROTH: Once you said, “I guess it’s because even if the character is based on my personal experience, I almost become schizophrenic. It’s not me. It’s almost like something outside of myself.”

GLOECKNER: It is. To me, it’s anybody.

GROTH: So, you’re trying to universalize that experience?

GLOECKNER: I feel that at some point all individual experience is human experience. You can take any experience and within that one experience say a lot about what it is to be human. Sometimes I’ll write what at first seems to be the same story I told years ago, but, because I’ve changed in the interim, the story takes on a different meaning. Memory is a very interesting thing. When you talk about facts, when you’re recounting things that happened to you, in a sense it’s just bullshit — as the years go by, memories are reduced to what’s significant to you emotionally. What’s important is how the experience changed you, not that it actually happened. Which makes me question my own recollections, because I know they are so mutable over time. That’s partly why I recoil at my work being called autobiographical, because that suggests that what I’m saying is true in a way that it could never be.

GROTH: Yeah, you’ve said there is no truth.

GLOECKNER: Yeah, I believe that. The basic question of art, of any art, is, “What is it to be alive?” It’s not a matter of truth.

The Mutability of Memory

GROTH: Let me ask you a question about how you’re using the word truth. Are you using it to mean accurate to what happened or are you using it in a more universal sense? It seems to me that you’re being true to human experience. In other words, you’re looking for a truth if not the truth.

GLOECKNER: Yeah, sometimes you have to distort “reality” in order to express what you feel is the true feeling. A recounting of facts can carry little meaning. An artist imposes a certain order on perception…

GROTH: Right, and when you refer to true feeling, you’re acknowledging that there’s such a thing as truth.

GLOECKNER: Yeah, you feel it.

GROTH: So you’re you’re trying to get at something we could agree is a truth.

GLOECKNER: A truth, right, but if I’m asked the question, “Is this a true story?” I don’t know... I’d always say “no.”

GROTH: You mentioned the mutability of memory, and how it shifts with time and subsequent experience, but it seems to me that your work, even when you go back and do a story that overlaps with a previous story, or tackles much the same subject, that the stories are still very consistent. I don’t see much in here that shifts and changes. You did two stories, and twice you had your step-father say something to the effect of, “Who wouldn’t want to be fucking a 15-year-old?” The language was almost identical. So, that clearly is something that didn’t shift with your perspective.

GLOECKNER: Right, but everything around it shifts. The interpretation of that comment. I mean, that often happens — you remember something someone says that they might not remember saying, and you might even forget exactly when they said it or where, but it’s something that for some reason either confused you or affected you in some way that you just remembered and replayed. What does that mean? “Who wouldn’t give anything to be fucking a 15-year-old?” What does that mean, exactly? I don’t know.

GROTH: I think you’ve been adamant that you don’t see art as therapy.

GLOECKNER: No, I don’t.

GROTH: What do you consider the difference between art and therapy, because in a sense they’re both trying to come to grips with something and trying to come to some understanding and achieve an insight into human experience.

GLOECKNER: Yeah, but they’re not the same. What’s that quotation from Edgar Allen Poe?

Thank Heaven! the crisis —

The danger is past,

And the lingering illness

is over at last —

And the fever called “Living”

Is conquered at last.

Death is a moment of celebration. Life is a fever, a sickness, and we can’t recover from it … I’ve always felt that my feelings are so close to the surface that if don’t express them somehow I’ll implode. Everything seems almost too vivid. There’s no cure for it. Art doesn’t seek a cure. Therapy does. I’m not trying to cure myself with my art. The idea seems ridiculous.

GROTH: I agree with you entirely, but I wanted to find out why you felt that way, since they do have overlapping goals.

GLOECKNER: Therapy is a day-to-day thing. It’s going to change your attitudes; you’re going to deal with this person and that person …

GROTH: One is very utilitarian, and the other is more …

GLOECKNER: The other is larger. You know, the therapist doesn’t know why you’re alive, or why she’s alive. The therapist doesn’t understand life.

GROTH: The therapist’s job is to tackle very minute problems, very finite problems.

GLOECKNER: Not always minute or finite, but more immediate problems, like interpersonal relationships. But that’s not all of life. That’s not like the angst we feel when we look at our hand and realize there’s blood coursing through it, that horrible realization that you’re flesh and blood. That, in itself, is as fascinating and painful as anything else, and your therapist isn’t going to help you resolve those feelings of horror at being alive. It has nothing to do with your upbringing.

GROTH: You think it’s just the state of existence?

GLOECKNER: Right.

GROTH: So, you’re a true existentialist?

GLOECKNER: I did read Nausea at a very young age, and I remember thinking, “Exactly. That’s exactly how I feel!” But I would never say I’m an existentialist.

GROTH: Pascal had a great phrase, he said “The heart has its reasons which reason does not know.” For me that sums up a lot of the tensions and contradictions of life that you have to deal with.

GLOECKNER: Right, and it makes you understand that after a certain point, therapy is useless.

GROTH: You just said something about blood coursing through your veins; now, I could be completely wrong, but you don’t seem to believe in the dichotomy between mind and body that so many people do. One of the interesting things I discovered was that you went to medical school, medical illustration school, and you said at one point that one of the reasons you did this was that so you could watch autopsies.

GLOECKNER: Yes. I went to graduate school in Biomedical Communications.

GROTH: Why was that important? To see autopsies? Was that important to you as an artist, or for other reasons as well? If you make a distinction between being an artist and, I don’t know, some other part of yourself.

GLOECKNER: My grandmother was a doctor. She talked about diseased livers and death at the dinner table — in a detached manner. It was very interesting to me, but other people at the table would howl, “Oh, Louise, please don’t talk about those things at the table.” That was her name, Louise. I found her fascinating. Most doctors don’t have medical journals in their waiting room, but that’s what she had. Instead of Redbook, Time, and Sports Illustrated, she had The Journal of Surgery, Gynecology, and Obstetrics. Her office was in the front of her house, and when I went to visit her, I loved to sit in the waiting room and read her medical journals.

GROTH: About autopsies, you said, “I can see surgery. I could do my own dissections. I could go as deeply into the human body as possible. I wanted that because that’s what drives me — a constant desire to go deeper into the psyche or into the body.”

GLOECKNER: Right.

GROTH: Now, I think people usually see those two as very distinct and separate types of pursuits: the psyche and the body. But you almost seem to conflate the two, and that interested me.

GLOECKNER: Well, I don’t separate them because … they’re not the same, but they’re inseparable.

GROTH: You don’t see them as separate entities?

GLOECKNER: They’re not. To separate them is a very Christian/Catholic idea. You have to believe in heaven in order to believe that your body and mind are separate. It’s a hierarchical way of organizing the world. Flesh is of the devil and the spirit is godly. I find that hard to believe because it’s not my experience. My experience is that I am my body. My brain is my body. I wanted to see brains and see what it was that I am.

GROTH: … and a lot of your comics are about what you’re doing to your body.

GLOECKNER: Are they?

GROTH: Oh, sure.

GLOECKNER: See, I don’t even know. I didn’t think so.

GROTH: For example, “Minnie’s Third Love or Nightmare on Polk Street” where you could be considered to abuse your body, substantially.

GLOECKNER: Well, or use it, you know.

GROTH: In the last panel of that story you show Tabitha really ravaged because of the life she led. So there is, throughout your work, this kind of …

GLOECKNER: I think you could say that about anybody’s work, any kind of story. If I drew a frame with someone sitting down, you could argue just as well that I’m concerned with physicality … I mean, so what? I don’t see how that is … Anyway, I don’t agree with you exactly.

GROTH: I think you pay more attention to physicality than a lot of cartoonists. I mean if you take someone like Bill Griffith, for example, I mean, the body per se is not really that important.

GLOECKNER: Because it’s covered with a muumuu?

GROTH: I mean, it’s more about ideas, and his figure drawing is more about expressing his ideas than it is about the tacticility of physiognimy.

GLOECKNER: I guess. [Pauses.] Yeah, maybe. I don’t really … I’m just resisting that characterization because it doesn’t feel right to me. A lot of people have done stories about drugs or profligate behavior, or war, anything that involves bodies. I mean, it’s hard to escape that. Maybe Bill Griffith is an exception. But I don’t think so. In fact I know he’s not.

GROTH: I guess Crumb certainly is more in that vein. But someone like Spiegelman is not.

GLOECKNER: I just don’t know what you’re driving at. I think I’m just as concerned with ideas as most artists, and some of those ideas concern carnality — not necessarily sexuality, but corporeality …

GROTH: But I mean, with Spiegelman, for example, his figure drawing is more symbolic and his interests have less to do with the flesh than …

GLOECKNER: I think Maus … I mean, the mice are used exactly as if they were people.

GROTH: Yeah, they are enormously expressive, but I think one of the whole reasons he chose the metaphor was to somehow abstract himself from representational drawing.

GLOECKNER: But his drawings of mice are representational drawings. He’s not an abstract artist. I think you’re right that the mice are a metaphor, but mice are flesh. I also get the feeling that he doesn’t feel as comfortable drawing people.

GROTH: But integral to your work is a really high degree of representational drawing. You’ve done a couple of stories where it looks as if you executed the drawing very quickly, and those have a radically different feel to them. Of course, they still deal with pretty much the same subject matter.

GLOECKNER: You see, it’s weird to look at A Child’s Life, because this book is work over such a long period of time.

GROTH: You once mentioned to me that this sort of sketchy drawing you did, you actually wanted to do more of it, and that you enjoyed doing it. Can you tell me what that quicker approach to drawing gives you that the more labor intensive drawing does not?

GLOECKNER: I’ve done a lot of drawing where I’ve tried to draw things the way they look but, of course, as a cartoonist, you have to draw so many different things — there are so many different people and so many different perspectives and points of view that you just have to draw almost totally out of your imagination. You might be looking at a sweater or somebody or picture or photograph or something as a reference, but that can only go so far. You end up inventing almost everything. I look at A Child’s Life, and much of it was really bad.

GROTH: Bad?

GLOECKNER: Yeah, I mean, you know it’s kind of creepy to look at. If I look at it just for the drawing, divorcing it from the content, some of it just gives me the creeps. I won’t look at it; I’ll turn the page.

GROTH: You mean the drawing itself or the content?

GLOECKNER: The drawing itself.

GROTH: Really?

GLOECKNER: Yeah, but I’m looking at it and I’m trying to think what I was trying to do or how I was drawing. What was your question?

GROTH: What I think I was trying to get at was this: most of your drawing is really labor intensive. It’s not a big foot style. Crumb has a couple of different approaches. I mean, his earlier work was more cartoony and then when he draws something like a biography of a blues musician it’s much more representational. But most of your work is really carefully rendered and representational in its detail. And then you’ve done at least a couple of stories that were very sketchy. And I’m not sure if they were done in watercolor or wash or what.

GLOECKNER: Watercolor, right, they’re really in color. OK, I know what you are saying. No, in general, I’m really myopic. I have very, very bad vision, so I always got really, really close to my paper and didn’t want anyone to see what I was drawing and had my hair all over the thing so they couldn’t see. And also, I had this tendency, a kind of horror vacui —that made me want to fill up every space. In some of the work I did when I was really pretty young, I couldn’t leave any white space. Everything had to have a pattern on it. If there was a wall that was white, I had to cover it with something. I couldn’t stand blankness. And it was also the influence of many of the artists I was looking at: many medieval painters, and cartoonists like Diane Noomin. She fills everything with patterns.

GROTH: Do you consider this lack of negative space a visual flaw in your work?

GLOECKNER: No.

GROTH: Do you think you’ve addressed this and opened up your art more recently?

GLOECKNER: Well, I opened up my work a bit — I think you must be referring to the Diary of a Teenage Girl — this was to suit the book more than a solution to something I saw as a problem in previous pieces.

GLOECKNER: Well, I opened up my work a bit — I think you must be referring to the Diary of a Teenage Girl — this was to suit the book more than a solution to something I saw as a problem in previous pieces.

GROTH: You referred to your cartooning as initially an entirely secret affair; can you tell me what you meant by that and why that was the case? This was when you were maybe 15 or 16.

GLOECKNER: Yeah, because the very first, well, they were dirty and I didn’t want anyone to see them. So, it was secret.

GROTH: You were self-conscious about that?

GLOECKNER: They were about things that I didn’t want anyone to know about. So it didn’t make sense to show people, right?

GROTH: Right. One of your earliest comics was “Mary the Minor” — I don’t think it was the first one, but it was a really early one. It’s a three-page story, published many years later in A Child’s Life. Four years later you completely re-did it and turned it into a four-page story that was very different. That one appeared in Young Lust. You completely redrew it.

GLOECKNER: But it’s not even about the same … It’s not the same story, is it?

GROTH: No, it’s a very different story. But the title is the same.

GLOECKNER: So I didn’t just redraw it. I wouldn’t do that … I wish I had it in front of me. Now I can’t remember how it’s different.

GROTH: It’s more about your adventures on Polk Street. So you just took the title and then completely rewrote it.

GLOECKNER: I did a whole bunch of comics called “Mary the Minor.”

GROTH: Oh, you did?

GLOECKNER: Yeah! They weren’t published. The one that’s in A Child’s Life is maybe the first one I did. I put it in there, but it had never been published before either.