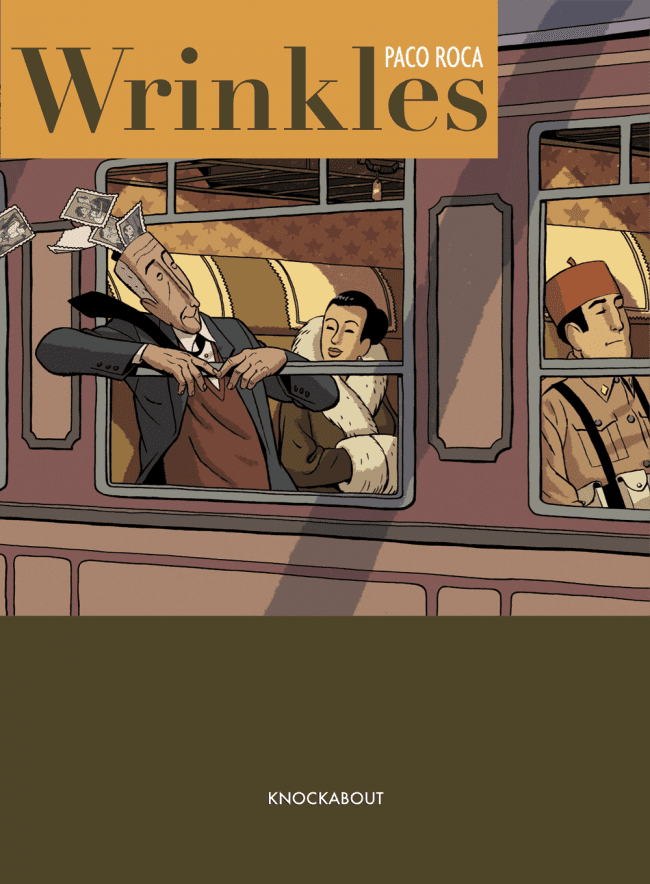

"I wanted to understand what it feels like to grow old in a society that is making the elderly invisible," explains Paco Roca of his graphic novel Wrinkles about Alzheimer's disease. The Valencia artist is at the crest of a true-to-life wave in contemporary Spanish comics. The graphic novel Wrinkles from UK publisher Knockabout this January marks the long overdue translation to English of Spain's Paco Roca, the arguably most prolific artist-author to emerge from the legendary El Víbora magazine since Max and Marti in the 1980s.

Born in 1969, Paco Roca was 30 years old when he made his mark in the magazine with the unpretentious action series Road Cartoons. He had previously made some short erotic comics for Kiss Comix. With more than ten years worth of experience as a professional artist in advertising, he had absorbed various styles and learnt technical skills that impressed the editors of El Víbora. After contributing several slick and detailed front page drawings of scantily clad women, he gained entry to the magazine's comics pages.

Even though English translations are few and far between, graphic novels from Spain have lately become increasingly more visible across the main European comics markets in France, Germany and Italy. The poignant Wrinkles, about Alzheimer's disease and day-to-day life in a retirement home, is at the crest of this new Spanish wave.

Wrinkles (in Spanish: Arrugas) was a huge commercial breakthrough for Paco Roca when it was published in Spain in 2007. The protagonist is a retired bank manager who has Alzheimer’s disease and moves to an institution. Roca convincingly portrays the rituals of the retirement home, and how this man gradually recognizes and attempts to handle the disease. The book has been adapted to an animated feature movie, with an award winning script by Roca himself.

The book became a bestseller, acclaimed by critics and has won all there is of Spanish comics awards. Wrinkles became in many ways larger than itself, and was received as the frontrunner of a new wave of Grafica Novellas. To quote a newspaper headline: "The new superheroes are elderly with Alzheimer."[1]

Roca together with Miguel Gallardo released a book, Emotional World Tour, about the fuss surrounding the original releases of Wrinkles and Gallardo’s autobiographical María y yo [2] (Maria and I) about his daughter's autism. The two books were promoted with the slogan "cartoons and social reality", and Roca and Gallardo jointly travelled on countless festivals and book signings.

Remembering The Civil War

Last year, Paco Roca received the main award Gran Premio Romics at The International Festival of Comics, Animation and Games in Rome for his most recent book, Los surcos del azar (Grooves of coincidence). The book tells the little-known story of the Republican soldiers in exile who after their defeat in the Spanish Civil War fought along with the Free French forces and led the liberation of Paris.

Even in one of his first books, El Faro (The Lighthouse) from 2004, Roca explored the Spanish Civil War. The book is based on a young Republican soldier who escaped from the war in a remote lighthouse. Roca develops the incident into a story about the necessity of imagination and illusions to survive. The protagonist finds shelter in the world literature of Don Quixote, Moby Dick and Gulliver.

Besides his graphic novels, Roca is also working on shorter pieces. In particular a two-page series called Memorias de un hombre en pijama (The Memories of a Man in Pyjamas) for national newspaper El Pais. Roca alternates with a series by Max in the paper’s weekly magazine supplement. The Seinfeld-inspired and partly autobiographical series originated in 2010 as a strip in Valencia newspaper Las Provincias.

Spanish Comics: Turning to Realism

According to lecturer at the University of Southern Denmark Anne Magnussen, who has a doctorate in Spanish comics, in the past ten to fifteen years there has been a growing public debate in Spain about the civil war and dictatorship, and new comics are involved in this debate.[3]

She points out that the ruling centre right party People's Party believes the debate is unnecessary and outright harmful because it opens old wounds. After the demise of the dictator Franco, the old monarchy was still retained, Spain did not make significant changes in social institutions and there was no commission that investigated the human rights violations that had been committed. After a failed military coup in 1981 and the Social Democrats’ victory in the 1982 election, the nation directed its attention to the future. The civil war and Franco regime was considered an embarrassing past that one would not dwell on, writes Magnussen.

This is reflected in the comics of the eighties, which primarily wanted to challenge middle class puritanism, cultivate (post)modern urban living and were particularly conscious about style and surface – marked by input from both American underground and French-Belgian ligne claire.

In recent years there has been a turn to realism in Spanish comics. Not unlike the way Carlos Gimenez and other creators in the 1970s made comics against dictatorship and criticised the lack of exposure of the Franco-era atrocities in the transition to democracy. Gimenez has more recently made the ambitious 36-39 Malos tiempos (36-39 Bad Times) about the civil war. [4]

Several books are about, or at least touch upon, the civil war. Alongside Los Surcos del azar, Vicente Llobell Bisbal’s Un médico novato (An Inexperienced Doctor) has been one of the most talked about and acclaimed graphic novels. [5] The experienced artist tells the story of his father who just after graduating in the autumn 1936 witnessed the regime abuses and was imprisoned for a short period as a military doctor. His father's hopes and ambitions collide with a Spain heading into civil war.

Basque writer and literature professor Antonio Altarriba also tells his own father's story in El arte de volar [6] (The Art of Escaping). The book covers his entire life span, from Primo de Rivers dictatorship in the 1920s until he commits suicide at a retirement home in the early 2000s. He was an anarchist and was living in exile for a decade after the civil war. This is a story of loss at different levels, where the personal and collective history unite in a strong generational novel. Altarriba has also written the noir book Yo, asesino (I, Assassin), which recently received the award to best comic of 2014 from the French comics critics association (ACBD).

Tales of adolescence and relationships in present day is another theme of the Spanish graphic novels. Gabi Beltrán recounts in Historias del barrio [7] (Stories from the Quarter) autobiographically about his teens in 1980s Mallorca, with the southern island's tourist invasion as cultural backdrop. Cenizas [8] (Ash) by Álvaro Ortiz is a fictional narrative, creating a strong emotional resonance from a hackneyed premise: Three friends who have not seen each other for a long time must squeeze together in a tiny car on a road trip to scatter the ashes of a dead common friend. Strokes of surrealism, a charmingly naive line and essayistic derailments on everything from Munch and Mengele to cremation makes for an original reading experience.

A book that actually has been translated into English is Alfonso Zapico’s Dublinés [9] about the author James Joyce. The biography spans his life from cradle to grave, with an emphasis on his intimate relationships, travels and encounters with other writers. The book is rich in detail, and especially impressive are the cityscapes from Dublin where Zapico stayed for several months and developed his art at street level.

The Interview: Visiting Valencia

Roca's weighty tome Los surcos del azar has in various media been received as a Spanish Maus [10]. This is, of course, an even more convincing argument to book a flight to Valencia, than the famed sunny weather of the Spanish east coast. In downtown Valencia, Paco Roca greets me in his large loft apartment. Between the residential rooms and the art studio, there is an open terrace with a small climbing wall. The studio has sliding glass doors, and he tells me that he often draws in the outdoors. That's at least what the interpreter, teacher Belén Canós, tells me. She keeps the translations running both ways, rescuing me and Roca from communicating through signs and gestures only.

Morten Harper: I'm very impressed by the gripping yet unsentimental way you handle Alzheimer's disease in Wrinkles. Could you explain to me what lead you to this theme?

Paco Roca: There are some things I dread or they worry me. If you are completely happy, you do not create. And growing old is, of course, in many ways worrisome. So in a way there is a selfish dimension to this: I wanted to understand what I have in store. But I also have a friend whose father got Alzheimers. That was important. It was also an eye-opener for me when I was assigned to draw an advertisement featuring a large crowd of people that was entirely without any elderly people. "They are not aesthetic" was the client's reply. And of course: That my own parents are old and have health problems made me interested in the topic. I wanted to understand how they experience growing old in a society that makes elderly people invisible.

Do you think Wrinkles and Gallardo’s María y yo, which were marketed in tandem, have changed how comics are perceived in Spain?

If they had been released five years earlier, people would not have noticed them. Wrinkles came out exactly at the right time. Earlier, comics only existed in separate stores, whereas in 2007 large chains like Fnac and El Corte Inglés had begun selling comic books. There was also a new kind of media coverage. The books were reviewed and the papers discussed the topics we illustrated. This has made a fundamental difference. Now a newspaper like El Pais can write about for instance fantasy comics without the journalist needing to connect it to some event or any other particular excuse.

The Spanish Civil War is evident in several of your books, not at least in Los surcos del azar, your most recent graphic novel. Why is this subject so important to you?

I think many people even in Spain do not know very much about the civil war. Franco's rule put a lid on it, and after the fall of the dictatorship we chose not to dig a lot into the past. I was six when Franco died and have grown up in a democracy. Refugee camps and Spaniards in exile in France, that was not something I learned of at school. I heard about it through a friend whose grandfather had been in such a camp. I think it is a problem when such an important part of history is not made more accessible or is openly discussed. More than thirty years of dictatorship has consequences that we now pay. There are still politicians who have never condemned Franco. A similar indifference towards Hitler would be unthinkable in Germany.

I find your stylized realism in Los surcos del azar simultaneously detailed and elegant, evoking the time era. The book also has sequences in the present, where you meet one of the Republican soldiers. These sequences are drawn with less detail, a thinner line and in a near monochrome grey-blue tone. The book alternates several times between past and present, and we eventually realize that this encounter is a fictional device – isn't it?

Yes, that's true. To understand history, I found it better to start in the present. By describing the present, we understand the disappointment of the exile soldiers. They are betrayed by both Spanish and French authorities. With the present knowledge, we may understand their motivation for not returning to Spain. At the same time, the images from the past shows us the facts there and then.

Your passion for the arts and craft is evident in your third main graphic novel, the docudrama El invierno del dibujante (The Artists’ Winter). The book of course unfolds in the late fifties Barcelona, where five of the foremost cartoonists at the major publishing house Bruguera launch their own comic book. Bruguera uses its market power to prevent the distribution of this comic. In what way do you feel the story is still relevant today?

They lived in a grey, colourless Spain after the civil war. When drawing they felt free and alive. I identify myself with their struggle to claim and own their characters and comics. They were dreamers. They wanted to make a comic book exactly the way they wanted it to be. I feel the same when I draw my comics today.

You started out doing illustrations for advertising at only seventeen years old. What lead you to the comics?

Advertising is well paid, so it is difficult to leave the field. But I wanted to create something more independent or creative, and I've always been fond of comics. So, of course, it was a great inspiration for me to become part of the El Víbora magazine.

Talking about your stylistic influences in comics, could you mention some artists you've admired in particular and been inspired by?

From El Víbora it's of course the great Max. I could also mention Milton Caniff, Richard Corben and Liberatore. I was wildly impressed with Corben when I was young. Each of his frames were a richly detailed illustration. I wanted to do the same. Eventually I discovered that a frame is more comparable to a word in a sentence. It is not necessary to overwhelm the reader all the time, actually the reader is usually more concerned with the storyline than the artwork.

Today, your style reminds me the most of Milton Caniff and American fifties advertising. If the art work has a nostalgic flair, the technique is modern. It was interesting to see how you usually work with a drawing, moving countless times back and forth between the pencil and paper of the drawing board and processing the images on screen.

I always start with sketches in pencil on paper. It is important to me that the result looks and feels organic. Often I see on screen that the shading I do on paper goes beyond the lines of characters and frames. I rarely change this. The drawings cannot be clinically perfect.

Besides the graphic novels, You are also doing the two-page series Memorias de un hombre en pijama for El Pais, which originated as an even shorter strip. Is this your Idées Noires, blowing off steam from working on the epic graphic novels?

The series started as a comedy about nothing, but the two-page format demands more content and is more challenging. Short ideas must be stretched out, and stories must be compressed to fit in. I'm also working on a movie adaptation of the series. This is actually what is haunting me now. It’s been difficult to write a script that comes together from the very episodic comic.

How autobiographical is this man in pyjamas?

He resembles me somewhat. My childhood dream was to be able to stay at home in pyjamas all day. And of course now I can – if I want to.

[1] Quoted from Emotional World Tour, Astiberri 2009, page 55.

[2] Maria Gallardo and Miguel Gallardo: María y yo. Astiberri 2009. 64 pages.

[3] Article «Mara and Paracuellos – Interpretations of Spanish Politics from the Perspective of the Comics » in Scandinavian Journal of Comic Art # 1 2012.

[4] Todo 36-39 Malos tiempos. Debolsillo 2011. 336 pages.

[5] Un médico novato. Ediciones Sins Entido 2013. 150 pages.

[6] El arte de volar. Ediciones de Ponent 2009. 208 pages.

[7] Historias del barrio. Astiberri 2011. 152 pages.

[8] Cenizas. Astiberri 2012. 188 pages.

[9] Dublinés. Astiberri 2011. 232 pages. English edition: James Joyce. Portrait of a Dubliner. The O'Brien Press 2013.

[10] An example: La Voz de Galicia 14.02.14.