Yesterday afternoon I walked to the Picasso Museum, walked because I wanted to try and avoid the gendarmes, flashing lights, and soldiers. Nevertheless, I could hear the sounds of emergency all over Paris. While I crossed street after street, police motorcycles flew by.

I was out because in my purse I had the invitation to an event. It was a "concert with live drawing," a celebration scheduled to link the Musée Picasso and the graphic novel PABLO. (A bestseller in France, come April PABLO is due in English from SelfMadeHero). I love this four-volume series and wanted to see its authors in action .

Yet how could creators Julie Birmant and Clément Oubrerie be expected to "perform?" Ever since 11:30, when five of the most beloved artists in France were gunned down at their work – along with seven colleagues – the capital had been in both shock and semi-lockdown.

The perpetrators were on the run and still out there somewhere. All over France, landmarks, schools, and transport were on full alert.

But when I entered the museum's courtyard, I saw queues of people. Tourists, students, French retirees… it all looked perfectly normal. Past the usual guards, down a flight of stairs and through rooms of Picassos – it was fairly easy to find the auditorium. When I got there, the place was almost packed. The show was going to go on.

Even in the quietest of seasons, Paris is always two cities. One is the capital of wonder-struck tourists, travelers who navigate everything in slow motion. But then there is the other Paris, the not-going-anywhere Paris. This, a city at work, fills the hours and pavements with fast walkers and rapid talkers.

The morning's horrific news had given the truth surreal dimensions. Even in the quiet auditorium, there was a stark difference. Half the audience were trying to compose themselves. Clearly tense, they kept rewinding scarves and checking their smartphones. But the rest were largely, blissfully unaware of the news. Giggling with anticipation, they gossiped and waited to see the drawing.

Down went the lights and out came Birmant and Oubrerie, in the company of accordion player Pascal Contet. Oubrerie stationed himself at a desk rigged with an overhead camera. Across the room from him, Birmant took up a microphone. "We need to ask for your patience," she then said, almost inaudibly. She wasn't sure, she added, if everyone knew the news. There had been a serious attack in Paris, on Charlie Hebdo. In it, each of them had lost good friends.

"Des parents…" she paused momentarily. Kindred.

After waiting a beat, Birmant started talking about Picasso. She described discovering Intimate Souvenirs, the long-forgotten memoir by Picasso's first love Fernande. The book had opened the doors of a vanished world. In it, she had access to extraordinary moments and personalities – that whole vanished, communal life which turned Pablo into Picasso.

As Birmant spoke, Oubrerie drew. The work of his hands was projected between them onto a giant, vertical screen. His scenes took form magically, every line assured and expressive. Clearly, he was drawing old friends…something that was both beautiful and awful to watch.

Somewhere else in Paris, another pair of hands were working. Although writing, they were engaged in a similar task. It was Laurent Joffrin, the editor of Libération – who was trying to honour his métier by capturing other old friends.

Today, his words were published. He wrote, "They have have killed Cabu! They have killed Wolin, Charb, Tignous, Bernard, Maris, and the others! Charlie and its gang, they were our cousins… Charlie was laughter, the intelligent laugh, the ruthless laugh. The derisive laugh. Charlie was the laugh which refuses tragedy… a Voltaire in vignettes and a kick up the ass of fanatics. Against pencils, charcoal and speech bubbles, they lifted Kalashnikovs. What an admission of weakness! Only when one has no arguments does one pull the trigger."

Back in our auditorium, Birmant was describing a storm in Montmartre. As she spoke, Contet plucked the sounds of rain from his instrument. On the wall, a model took form in front of Picasso's easel. Picasso… who was then just a Spaniard, a yet-to-assimilate foreigner. Who was just a shy, dark young man mocked for his speech and his dress. Picasso – one of the immigrants who helped create France and her culture.

In terms of Picasso's early life, PABLO is as good as John Richardson's famous biography. Without diminishing or simplifying the artist's work, its volumes create a real portrait – trenchant and amusing. PABLO shows some of those things of which great cartooning is capable. As intellectual Bernard Pivot said on television this morning, "With just a few gestures but with huge spirit, this can say much more than an editorial – or a book."

Charlie Hebdo is not dead. It will come out next Wednesday with a bigger print run: one million. This fact was announced by Patrick Pelloux, the activist doctor who is also a Charlie columnist. One of the first to arrive at the scene of the massacre, it was Pelloux who notified François Hollande.

"Because Cabu and Tignous both loved the President," he told the press, "I called his mobile. I had to try three times. But, when he answered he said, 'I'll be there right away.'"

Hollande did come right away. Hollande, the President who has endured countless scathing caricatures – the man whose politics, love life and stomach are the subjects of constant ridicule.

Hollande came not just because he is President and this was a true atrocity, a terrorist act. He also came because of what this art – the art of comics and BD and cartooning – means to the whole country. He came because the work of its best auteurs speaks to everyone. Because the art matters at deep levels to people of very different ages, races and roots. For all those holding up signs that say Je Suis Charlie, these arts are a symbol – a vehicle – of French liberty.

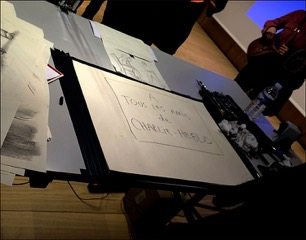

As Pascal Contet's accordion exhaled final chords, Clément Oubrerie picked up a new piece of charcoal. He bent over the last sheet of paper on his desk. "À TOUS LES AMIS DE CHARLIE HEBDO," he carefully wrote.

…For all our friends.

The trio finished, paused, and bowed. The audience rose to its feet. A few people started to applaud, but somehow that felt funny. Instead, they started to do something else – they turned and carefully, mindfully, kissed one other.