[A version of this article originally appeared in Hammerspace, a journal about animation edited by Lilli Carré and Alexander Stewart]

What kind of people read comics and watch cartoons? Increasingly, the answer becomes ‘every kind imaginable’ in the same sense that books, film and television are universal experiences. Children’s animation aimed at urban professionals alongside appropriated corporate comic storylines are now a core of our treacle laced shared culture. Most usually encounter all this passively, consuming visual storytelling as one might also chew gum: something to do with enjoyment but…with passion? Such an idea cannot be (unless the passion is of an angry, reactionary and political stripe). As all this tepid intake builds with increasing fervor (with very little at the center, signaling an inevitable comic book stye cosmic implosion), the character of those who are obsessed with cartooning seems to remain the same, slow and steady.

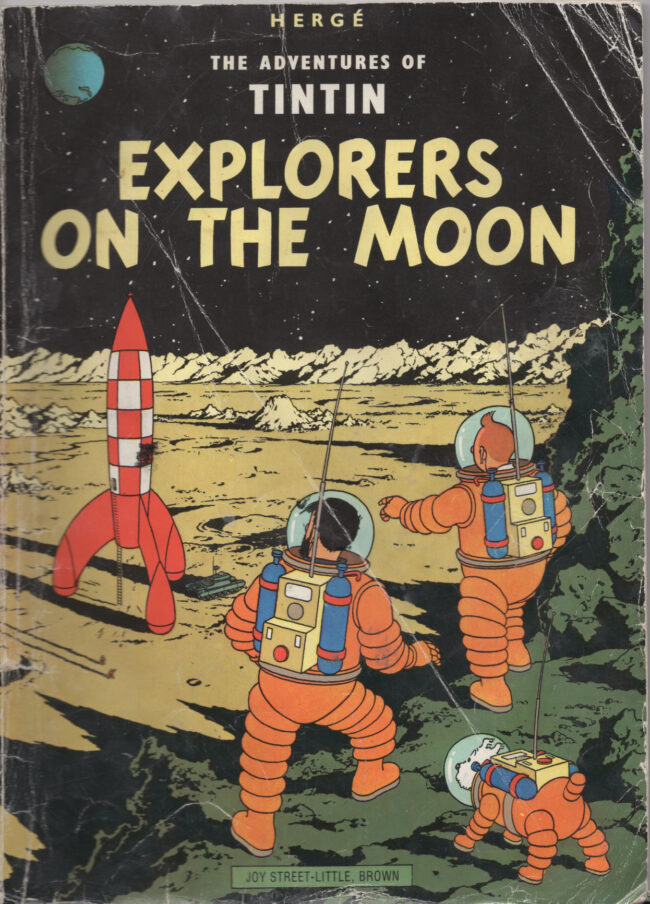

It often begins in childhood, with certain kids unable to ignore the gestalt of a cartoon characters design, the simple (non fantasy) reality suggested surpassing the one that served it up. I remember my entry into comics depended on a bookstore’s life-size cut out of Tintin himself, standing next to a pile of his publications. The character was too powerful to ignore, his adventures chronicled in book form suggesting a deep well of knowledge that demanded immediate allegiance.

Why? Whenever I hear similar stories of cartoonists or devotee’s of comic art telling similar origin stories, I develop amateur theories. For a certain kind of child, usually from hard scrabble backgrounds or mild/vaguely/extremely turbulent circumstances, stories that were drawn by hand seemed to provide something essential. The design of a character suggested a stable and straightforward friend, and then the form itself delivered far beyond this key. This typical kind of child reader who became obsessed usually didn’t have much, a cheap comic offering the first thing to view privately and methodically. The experience of reading these stories, in seclusion, offered an anchor of control: stop, start, toss away, return to with more devotion, whenever the time was right or worldly concerns allowed. A comic was simple, a thing that could be enjoyed with no one else, if no one else was around. For all the twisted young psychosis that these narratives were asked (or depended upon) to satiate, the form happily pandered, pluckily delivering flop sweat chaos within its sedate delivery system. A wild combination. Not petit pedestrian as to cater with a smile, but instead haute pedestrian, pandering with a weirdly unsophisticated kindness.

Comics for adolescents (beginning, arguably, with Lee and Kirby’s psychoanalysis and steroid heavy offerings) would offer the inevitable backlash to all this, but comics for very young readers were, for decades, the quiet mass form of the medium. One of the most lucrative examples was Mort Weisinger’s Superman Family line of comics, with sales hovering just under a million copies an issue during their salad days in the late 50s through early 60s. Because of their commercial ubiquity, the comics that Weisinger edited were (and continue to be) passed over and derided when it comes to artistic merit badges. Like dish soap, they simply exist, without comment. But Weisinger’s comics are, to me, some of the most beautiful the form have ever offered. His stories are almost fundamentalist texts for the young readers that inhaled them: controlled, icy, rule based worlds, with fairness and basic kindness systemic to the galaxy’s construction. A need for stability and respect satisfied, Weisinger then uses any variables left to lash out, sometimes with cruelty, offering heady thrills. Young readers are respected, as all is restored by each tale’s end. Before this happens, though, a gift of wild inventiveness, disconnected to any recognizable correspondence with reality, is given. Weisinger’s stories aren’t exactly imaginative but instead work as games. Curt Swan's 1968 cover to Action Comics #360 offers a dazzling admission of all this.

Weisinger's stories present the reader with a 100 piece puzzle, one that is easy for a child to finish, but upon completion presents itself not as a flat picture but instead a multi dimensional sculpture consisting, suddenly, of 10,000 pieces. For those from modest means, these puzzles offer a luxurious reward in the most dismally cheap packaging.

For the comic obsessive, reading a halfway decent book or viewing a barely artistic film ushers in an uncomfortable confrontation: even the mediocre sophistication of other mediums makes our comic 'masters' look rather shabby --to even attempt the bare minimum of coherence seals, for a comic, the status of classic (see: The Dark Night Returns and its ilk). Weisinger's work, when collided with from such a mindset, is treated as total embarrassment, worse than pap. This is where much of our already tangled thinking around comics begins to become labyrinthine. The purple prose (via the toilet) of Eisner nominated comics assures the insecure (and, as discussed above, discombobulated) comics reader that their medium is quite serious. Weisinger, on the other hand, offers queasy confirmation of our own palpitating self hatred. But it is Weisinger's righteous eschewing of other mediums pretensions that make his comics truly comics. Within the archives of this magazine's frenzied message board past, a reader sharply maligned an otherwise much praised literary cartoonist, saying 'translate one page of their comics into prose, it'll sound ridiculous.' The assumption that such ridiculousness was a defect reads now as a clear harbinger: today comics reside in a bookstore market in which they are irreversibly trapped and in a process of assimilation to the contents of a celebrity cook book (we thought we'd assimilate into Middlemarch but the road to hell and all that...). Weisinger's work is ignorant of all such conflicts, as his only multimedia analog is Hasbro (after all, the properties in Monopoly are the same as a panel), but one unconstrained by budget limitations around pieces and boards. Metaphysical Hasbro, maybe, but made by someone who, if they heard such a phrase, would deliver you a well deserved fat lip. You can view these comics as dismal failures in terms of their correspondence with virtually any other art besides Pachinko, or you can see them as comics ala Herriman ala McFarlane.

Panel from Mort Weisinger edited ‘The Super Duel in Space’, drawn by Al Plastino and written Otto Binder, in Action Comics #242, 1958Weisinger edited ‘The Super Duel in Space’, drawn by Al Plastino and written by Weisinger’s absolute best writer, Otto Binder, in 1958. The plot involves a villain, Brainiac, pressing buttons to scoop away entire cities (Paris, Metropolis, etc) so as to hold them captive in bottles. Superman falls into one bottle that happens to contain a lost city from his home-world, Krypton. Brainiac had stolen this city, Kandor, before the planet itself was destroyed, so within this bottle, Superman has a bittersweet rendezvous with his native culture. The drama of the story involves Superman returning all the major cities to their original place on Eath’s globe, except for his Kandor, which he is unable to save. The final panel shows Superman placing this city on a shelf in his Fortress of Solitude, as he remarks ‘Perhaps I’ll find a way to restore it to normal size and live with my people again…someday! Who knows?’

Weisinger’s story offers no connection to reality. There is no social commentary, no view of how people in the late 50’s acted or thought, even in caricature form. Plastino's drawings of the bottles that Brainiac traps cities in are not made of space age materials like a Kirby sketch might be, they are simply drawings of the most basic form of a bottle, meant to convey nothing else than ‘this is a container.’ All that Weisinger seems to care about is his artists ability to communicate concepts, as the bodies of characters in these stories have no correspondence to anything worldly except as an outlined shape. The only thing that matters is the universe within the pages, the ludicrous idea of a city transported into a bottle syncing up only with the ultra non real world that birthed it. While there is no nod to the newly inaugurated space race (which, in the real world, began a year before this stories publication via Sputnik), there are endless notes on other Weisinger inventions: the Fortress of Solitude, the increasing importance of Krypton and its properties, etc. etc. etc.

Weisinger’s concepts become strange, exotic items for a young reader, a treasure specific to itself. The overtly wholesome nature of everyone involved offers an obstacle free zone to enjoy the gift of these useless inventions at their full dizzying height. No one is scowling or poking fun at the silliness, but participating respectfully. Wesinger’s stringent rules (Superman’ powers don’t work on Krypton, The Fortress of Solitude is a safe space where precious things can be stored) allow the gift to remain concrete. There are no lingering questions, no further tomes of mystery to address tantalizing ambiguity: the bizarre concept exists in these pages solidly, a living breathing new idea captured and constrained. Grafted-in-stone-chaos for young readers with similar contradictions.

Weisinger, by all accounts, was not a kind man. He was a bully, whose tantrums and vicious insults towards his employee’s are well documented. The lack of intentional emotion in his stories is no surprise, as he was not a man given to wallowing in any public display of warmth. Marvel’s letter pages often contained catch phrases, winks and nods from the editorial team to readers, while Weisinger’s letter pages involved long admonishments towards child readers for asking dumb questions.

If anything else besides Weisinger's concepts were to work their way into his stories, it would be a mistake, something he couldn’t account for. One cannot miss, however, just how undeniably sad his stories are. Superman placing a city from his dead home onto a shelf of his solitary base equals isolation plus regret plus defeat plus no one to share the defeat with. Weisinger was not maudlin, there is no confession here, and Freudian speculation about an editor who was extremely meat and potatoes is not productive. I think Weisinger strove to let his universe of ideas contain as much as possible, and that he committed to giving his child readers something of value (as long as it was commercial and bridled). This value becomes highly charged the more Weisinger’s angry and sad demeanor syncs up with the chaotic mental space of his readers. The ideas are actual gold, uncovered riches never before seen, washed over with a foggy gauze of contradictions that reader and editor may try to deny but so obviously share.