The following interview was a highlight of the recent Entreviñetas festival in Colombia. It was conducted in English by the Colombian writer, editor, and scholar of comics, Pablo Guerra, and then was transcribed by Mr. Guerra for publication here at TCJ.

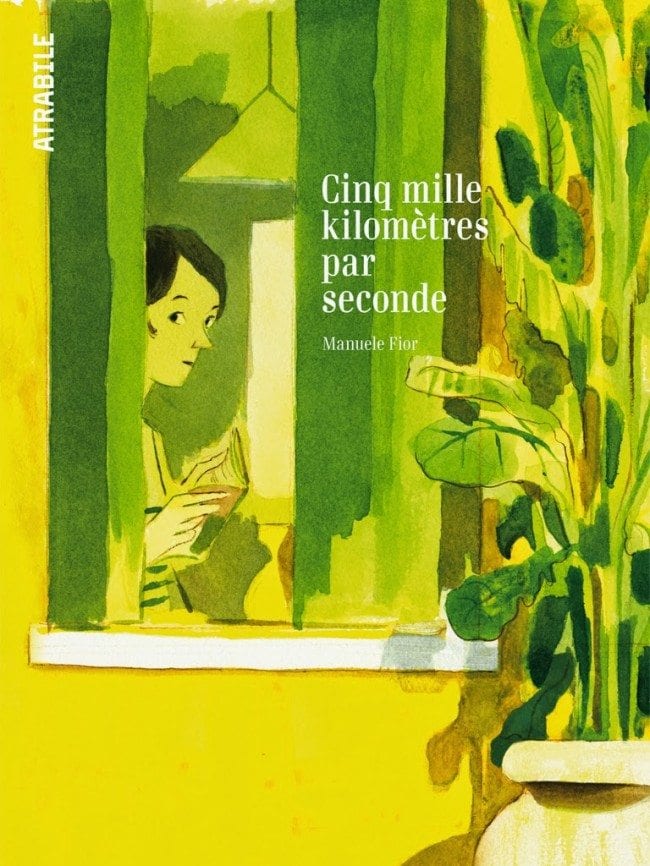

Manuele Fior is fairly unknown in North America. The Italian born author’s book, Cinq mille kilomètres par seconde won the Best Album prize at Angoulême in 2011. Fantagraphics is planning on releasing the book here. However, this was one of Kim Thompson’s projects which was unfortunately shelved after Mr. Thompson’s untimely passing. Hopefully, Fior’s work will see print here in North America and soon we’ll all be able to appreciate this master’s charm. Until then please enjoy this lively conversation between Manuele Fior and Pablo Guerra. —Frank Santoro

PABLO GUERRA: Welcome to Entreviñetas Manuele Fior. Hopefully we’ll be able to have an interesting and inspiring conversation about your work. Looking at it and seeing the fact that it has a very special, particular style, my first question is what did you have to learn to become the type of cartoonist that you are?

MANUELE FIOR: I always think I have to learn everything, in a way. Everything is important. Maybe somebody knows a bit about my career. I never studied art because my family was not so fond of art. My father was in the army and my mom was a teacher so I was never allowed to have art stuff, but we looked for a compromise so I studied architecture. In the beginning it was quite hard. I really refused it, but then I actually found that architecture helps me a lot in what I’m doing right now. Most of the time it would open my eyes. The problem of the comics world at the time, and in general, I think, is that it is often very auto-referential. Comics artists look at other comics artists – which of course is a very good thing – but they stay a bit closed inside this world. So architecture for me was also a way to clean up my eyes from styles of drawing that were every everywhere. There was this decade where everyone had to draw these Gothic girls and in the next decade there was another thing. So it helped me a lot to make things clear.

And in the last twenty years we can say the world of comics and the French scene has opened to a lot of techniques that also were not reproducible before. So you have to learn even more things. You have this phenomenon of this etiquette of graphic novels that sometimes produce very long books so people look at the movies as a real model for the plot, so you have to learn a bit also of the way movie scripts work – if you want to go on that direction, obviously. I’m learning a lot of painting techniques, because I never studied painting. I always wanted to learn it. I tried to learn it with my illustrations and my comics. Maybe there is something to learn also from music for instance. I never listen to music when I work but I am very influenced, for instance, by artists like [Igor] Stravinsky that mixed pop things with very classical structures. The concept of mixing [can be found] also in artists like Frank Zappa. It is very present in my mind. Also because [cartoonists] also work with a pop art, something that is bastard from the very beginning that has to mix references from everything. So [you have to learn] everything!

Regarding music, can you talk a little bit more about that dialog? Is it based on the rhythm that is set by a page layout or by how panels are distributed or by how that repetition creates some sort of rhythm?

I picked up Stravinsky because some of the ballads that he made very early [in his career] were a kind of total work of art. There was the music of Stravinsky, the dancing, and then, for instance, Picasso worked on the costumes of The Firebird, or Le Sacre du printemps. So it’s a mix of, at the time, excellent artists. When I listened to, for instance, a Stravinsky ballad there’s a lot of images that come to my mind that I try to keep. In this way I think that, these Stravinsky ballads are very narrative because they are sometimes based on Russian or pagan fairy tales and it’s like it is adapting a story with music and I am adapting stories into drawings. And then of course you can listen also to the Beach Boys and it’s also good. It can influence you in another way.

How has the evolution of Italian comics affected your work? Because I think, if I am not mistaken, you really began to make it as a comics maker in France. And Italian comics have their own pace and their own crisis and their own moments when they have slow down so it’s not a business anymore so you have to look for alternatives. How do you think being part of comics both in Italy and France has influenced your work?

I think it influenced me 100%. I see myself belonging to a certain Italian tradition of comic makers. The maestro for me, the reason I chose to make comics is Lorenzo Mattotti, maybe he is not so well known here in South America but when I read Fires, a Lorenzo Mattotti graphic novel from 1986, I decided to push for this job. And of course Lorenzo Mattotti comes from some comic artists in between Italy and also South America, Argentina, like Alberto Breccia, José Muñoz, Hugo Pratt. You know, comics in Italy have a very schizophrenic story: they were very popular in the '70s when Hugo Pratt made Corto Maltese, Guido Crepax made Valentina and in the end of the '70s beginning of the '80s there were two groups that revolutionized the comics world: Valvoline, the group of Mattotti, Igort, and Charles Burns, who was living in Italy at the time, and the other one was Ranxerox, with [Tanino] Liberatore, [Stefano] Tamburini, and Andrea Pazienza. When I read some comics of Andrea Pazienza and Mattotti it was clear that something changed forever. They opened a door I could never shut. It’s like the first time you see Moebius, you put some books in the box then you put some new books on the shelf, a new story opens its wings. That for me was Mattotti and Pazienza. So I am definitively sticking to it but of course I am living in France so I am very influenced by a lot of people, by the work of L’Association, the work of David B, we are sponges so we take a bit of everything so we make the best out of it.

Do you think you would have being able to make a living if you were only published by Coconino Press in Italy?

I would have died ten times. But still I keep publishing with Coconino because I love them. I travel a lot and really haven’t lived in Italy since 1998 so I happened to know a lot of people working in the comic world, publishers in Germany, Norway –also, strange publishers- so for me it was quite evident from the very beginning that I had to try to publish one book in German, in Norwegian, in Italian, in French, not because they are very successful books, not at all, but because we know each other, and this is a strange thing of the comic world normally in literature it doesn’t work like that. For a book to be translated in several languages has to be a real bestseller, comic books, and I think you can also have thousands of print runs but you must have them in several countries so I am living out of the several contracts that I signed in different countries.

From that perspective, do you think it is worth studying comics-making? Because you are spending all this time learning something you love, of course, but then you are supposed to make a living out of what you studied. Do you think it is relevant to study comics making as a formal program?

You mean in a school?

Yes.

I don’t know because I never went to a comics-making school. It is difficult to say because if you are taking just drawing, of course now, drawing as a 360 degrees possibility, you are not supposed to learn just one technique, if you think this is the good technique for you then you learn it properly. When I began to do comics and I was very fond of American superheroes: you had to buy the brush Windsor & Newton number 7, and then black Indian ink, and then learn to do all these small things that I could never do. But now this is one way of doing comics of course, and there are great people doing that in the mainstream world that I really appreciate, but I would never suggest anyone to buy the Windsor & Newton number 7 and learn how to write your name. I don’t know, I just speak for myself. The school was the school I made with my colleagues –being very jealous of some colleague— trying to steal something from everybody. And it is still like that. I am still in school. In Paris I have very good friends like Alessandro Tota from Canicola—he is a really good writer. Gipi was living in Paris also for a couple of years and of course it was a huge lesson.

For me he is one of those creators that when you get their book, you put away half of your book collection.

Of course. So, I would not go for a traditional school. No.

So now, I want to ask you about your creative process. Because I think in your books I find this very careful planning, or at least this very careful set up of every element on the page. So you have a plot that makes absolute sense in the form that you picked. Every single detail seems to really be a part of a whole thing and I’m wondering is it a more spontaneous process or is it a cold and very planned process? Or how do you mix those two things?

As you may know already, I don’t work with storyboards. So I don’t plan my books. This doesn’t mean that I’m just drawing. Normally there is a phase before where I try to know everything I can about some subject. For instance, the latest book I did, The Interview, I was fascinated by the issue of contact with extraterrestrials so I really watched all the movies I liked, I watched also these fake YouTube videos where they say: “Ah, UFO!” And then, since my main character is a psychoanalyst I think I read everything of Freud. But then when it comes to making the book I start drawing the first page and of course I have to choose the right technique. It takes some time to really find the right materials and then I start drawing the first page and then the second page and the third page and so on. For me doing comics is so slow that when have finished ten pages I have already thought the story a bit. For instance, in The Interview I wanted to start with a car crash. A friend of mine had a car crash outside of Udine, this small town where my parents live, and he talked about this car crash in detail. It was a vivid tale. He is good now.

So doing the scene of the car crash could take me one month and I have to learn the technique so in one month I have to choose a way out of the situation—Is he dying? Why did he had that car wash? You know, and so I try to go on. For me it is very important that one thing sticks to the other, I don’t conceive transition pages. Like pages that bring me to one interesting action to another interesting action. I try to care about all the frames. Not to think about transition. For instance when I go to an exhibition of Guido Crepax and I see a page of Valentina that is taken out of a book, I think it’s wonderful to read it. Not just to watch but to read it just like this. It stands alone, it’s incredible. It has a weight and a magnetism. It’s part of a book but it’s also a living page. You can imagine what happened before and afterwards.

How do you deal with characters? Your characters always seem to be hiding something. They seem to be much larger that just what you are showing. Do you start with the idea of a character thinking, “I want this to happen to a person” or an interesting setting and then start playing with characters?

I experience that when you build a concrete setting like for instance an architecture, in [The Interview] the main character lives a in Frank Lloyd Wright house --that is built in Italy, that is impossible, but... I studied a lot this Frank Lloyd Wright house which reminded me of my old career in architecture and so I studied plans and everything. So if you move a character inside this frame there’s a lot of ideas of what can happen and also about his life. For instance, he is kind of a frustrated man in his fifties that likes design in a kind of fetishistic way. So characters are exactly like the story in a book, it grown bigger on every page. You discover something of the character on every page but sometimes I see young people –young comic artists- that make a lot of these sketches, like for animation of characters. How do you call it, a line-up? So you see from every angle and I ask to myself, how can you do this at the beginning? You don’t know. And for me the problem is the character changes a lot that is why I don’t make the line-up. He transforms. And sometimes I have to go back and correct all ears, noses or sometimes wipe out the character and redraw it. With Dora [from The interview] I corrected a lot of frames from the beginning because she changed quite a lot. But I prefer to do it like this, of course after fifty pages or 100 pages you know the character a bit better so you can go back and see.

Dora is a very specific character. What called attention to the book for me was the choice of the cover; it is just Dora. She is a very specific person. She doesn’t seem like just a model applied that could be any woman, it is just her.

For Dora, the first idea for her is a drawing of Leiji Matsumoto, a Japanese comics author who made Captain Harlock. He draws the women all the same way: they are very skinny with long hair like a wire and he makes this thing that just Japanese guys can do; he makes like this big nose in the profile. If you make a big nose in Europe, it is just a caricature because a big nose means “ha ha ha.” But he makes this big nose that is wonderful so I picked this profile and I tried to invent a character that was laying behind this profile. When Dora appears in the story, you don’t know anything about her and me. I didn’t know anything about her but I tried to make her respond to the questions of the psychoanalyst in a certain way, in a punky way and it worked. So I thought about a 19-year-old girl with a punk attitude but who also is very idealistic and believes in strange things. Then I saw what happened.

Overall, how do you approach female characters? I don’t know if you intend to do it or not, but I think female characters have a key role in all your books. They have a transforming energy on every story. But they are not just a device, they are actual characters.

Most of the time, they are main characters. I realized looking backwards I never decided to choose a female hero. There is something related to the drawing. I love to draw women. I feel there is a very strong erotic part in drawing women. In general but also in characters I see in women like an unknown continent and you can only get to see the profile but you never discover it entirely. Unlike a male character. So I love to work with female characters because it will always escape my stereotypes. Most of the time girls or women in my comics they have the key to unlock a situation and them men follow and analyze what happened. It lays in a biological diversity. I will never understand what is going on in a woman’s mind. Stefan Zweig wrote Twenty-Four Hours in the Life of a Woman [1927]. He is also a very familiar author to me. I stick to this kind of literature also. It happened like that and I think I will keep going with Dora. For the first time I will keep a character and I will try to build my Corto Maltese. [laughs] No, it will be very different but I wanted to keep a character also to develop another story that has nothing to do with the previous one.

I want to talk specifically about your two latest books. Let’s talk first about Five Thousand Kilometers per Second. It’s a beautiful book, a very colorful book that shows this long lifespan of characters. And really allows us to see moments of high energy and then how that energy turns into a very depressing state of things. I am wondering, why did you chose to do that? And also thinking about what you just told us about how you approach your creative process.

Yes, Five Thousand Kilometers per Second was a fake autobiographical book. It takes place in some of the places where I’ve lived and worked: Egypt, Norway. But then, the events are invented so the characters go in these places like I went sometimes doing the same job and making different decisions. As I said, I traveled a lot so I felt the need to make some order out of my life. Sometimes with comics you can, or with literature, you can put it on the desk and see clearly what happens. I tried a bit something you should never do, that is to psychoanalyze yourself with comics or with your story. It doesn’t work very often but I had to experience that. The point was to make things happen between the characters and to make them react in a different way as I reacted, for instance, someone decided to leave, someone decided to go back and someone decided never to leave Italy. And as the characters, they really have my own age: in the beginning they are 16 in the same place where I was 16, when they are 50 they are in the future, of course, because I’m not 50 yet. So with this method I tried also to push my memories towards the future and see what would happen. To imagine a possible scenario, not of my life, but of my expectations. And I think also to exorcise some fears of failure, of making the wrong choices. So they take the consequences of the wrong choices instead of me.

Was it always thought as a full-color book? And how did you use color as a storytelling device?

Yes, I thought from the very beginning of doing a color book. And I had some experience with these colors, acrylics, because I’ve done really a ton of illustrations in Norway for a weekly newspaper, I did four every week so it was really a good school. After a year and a half I thought I have to start doing a comic book and I remembered I was visiting Mattotti in France, in his studio in Paris. At the time I was not living in Paris and I told him I wanted to do this book and he said to me, “OK, I know what you are going to do. So you don’t want to use outlines, OK.” He knows everything. So he said, “If you don’t want to use black, here’s what you need to use: brown (terra brochatta – burned terra), and either marine blue or green. So I wrote all the colors. [laughs] And I just used one, burned terra, and it’s the color that binds all story because the other colors changed. I used this system: I would never use more than three colors per chapter. So I began, for the first chapter: yellow, brown, and blue. Then blue and yellow to make green. And then in the second chapter I skipped one color, the yellow, and I put orange so you have like a candle rotation of colors. It’s like if you make like this [gestures flipping the pages of a book fast with his thumb] the colors change. And in the last chapter there is a flashback and the colors go back to the initial triplet. It’s like a history of color in a way. I share this opinion of Lorenzo Mattotti that color doesn’t come afterwards but comes before the drawing.

How was this book influenced by the creation of the European Union? You were a teenager when it started and this a definitively a book about not belonging, about a lack of roots and distance.

It influences this book as it influences all my life. I left Italy in 1998 because I won an Erasmus Mundus Scholarship. This scholarship in Berlin changed my life because I never went back to Italy. Of course there’s a lot of good things that come from making this kind of decision. I would have never done this job in Italy, or would have never made a living doing it. But then, after a while, when you have really decided you don’t want to go back and you stay in several countries, it is also hard because times are not always good; shit happens and then you ask yourself sometimes where do you belong. I’m still Italian just because I speak Italian but I don’t live in Italy anymore and there are a lot of things I don’t share now with Italian politics— and comics, actually. It can also sound like a bit snobbish to ask, oh, where do I belong? But it was really quite bad sometimes because maybe you broke up with your girlfriend and what do you do, are you not supposed to find a job, should you go back to Italy, where there is nothing, should I stay here, should I go somewhere else, should I do art, and you move around randomly. I came to Paris randomly, not knowing what to do. I’m still thinking that this possibility that the European Union gave us to travel and to pay in Euros is a good thing. It altered my life in a good way. But still there is a dark side of this that we should investigate sometimes. I know a lot of people that made the same choices in the same situation as me and it changes a lot of things.

Now, let’s talk about The Interview. In this book you make a big switch, you stop using color and you change the working method. Why did you choose to change it?

I am always using colors. What I did between these books was a lot of illustration, so I never quit using colors. But in this books I wanted to do something that reminds me maybe of the films of Michelangelo Antonioni in the '50s, like, La Notte, L’Eclisse, and L’Avventura. They are black-and-white movies. He has a way to compose the image in black and white that is very effective. And so I tried to look for a technique that could, not emulate the photo, but that could create this atmosphere. Black and white was the thing, and the material was charcoal.

I think The Interview is talking about feelings that disappear as we find new ways to interact and we lose others. There are new feelings that appear and others disappear. When I was reading it I associated it with the history of comics, in the sense that, for a while it seemed like comics where dying and then there are new voices and a new spirit for comics. What is the connection between the topic of The Interview and the language of comics?

I never thought of it that way. I actually never thought of like a metaphor for the history of comics. I looked at a lot of other comics in The Interview. Most of the time, Japanese comics – Osamu Tezuka, Leiji Matsumoto, [Yoshihiro] Tatsumi. The creator that maybe for me was very influential, as we said before, was Gipi, at least for my generation. He is not that much older than me, he is in our generation of comics-makers. [He] made something that was really important to us: to show themes from the Italian landscape that are not La torre di Pisa, Ill Colliseo. No, [he showed] the Carefour in the periphery of Firenze. So, watch the thing like you always have a camera on your shoulder and it is always open. You can’t take away the bad stuff. And this was really strong. And I followed also because I was very inspired by him, but somehow when I started to do my own stuff I thought that doing comics was not like having a camera on your shoulder.

And Osamu Tezuka makes fun of comics language all the way. You can change technique from panel to panel. There is a character and he mashes this wide space and I’m thinking more and more in this direction. Comics language has an alphabet and you should use it. Sometimes you don’t have to draw the whole character, you can draw it as a black silhouette. And if two people are talking and I see what lays behind you and you see what lays behind me, it is not worth to try to draw it all the time, at least in my case. Then you have Chris Ware who can play with it and make all this monotony. But I think sometimes you can also think in another way. Not being like the little sister of the cinema but being the brother.

In a way you are using a lot of literary devices that are deeply narrative and structural. How do you see the relation between literature and comics at this point? And even comics and other arts?

The comics I had when I was young, when I was a child, were all considered bullshit by the other arts. I think there is a good thing in comics being considered a subculture and popular stuff. I think there is always a genuine thing that people who were doing this were not obliged by some kind of social issue to make comics. Who knows why they make them but they feel the urge to express themselves in comics, so I’m not fond of these parallels with literature or the cinema.

I think we live in a pop world. Everything is pop. We are not living in the 18th Century. The definition of comics is a mix of high –if you want to call it like that – and low arts. But all other arts, even if they act like they are higher, they are a mix of pop things. You can’t escape from it and it’s a good thing for me. It’s the reality of our times, undeniable. But you should not think the other way around, [that] you should spit on literature. There’s also good stuff in it. So if I do a comic, on the desk I also have maybe a book of Dostoyevsky and Batman and then Osamu Tezuka and then some stupid Japanese animation, I don’t know what, and then a postcard of Bosch, Kramer’s Ergot, everything you want and they are not ordered in a hierarchical system—they are just mixed. The good thing of comics is that, more than pop music right now, there is a relation between author and reader that is really genuine. In contemporary art, they dream about this. They communicate only with filters so that if you see an exposition of [Maurizio] Cattelan or another contemporary artist—I mean, I like him a lot but most of the people come out from the museum and think, “What should I think about it?” I think I like or I don’t like comics. You can say it’s boring. If you don’t like the Beatles, I can burn you ten albums of the Beatles –listen to "The White Album"—but you will not like it.

So in a way it is sort of like the other way around it, the canon of literature is part of comics in a way.

For instance, right now I’m doing a comic book on the Musee D’Orsay, the museum of Impressionism, and the funny thing is that you see a lot how the post-Impressionism was the beginning of the Art Nouveau style that also produced comics with Winsor McCay or The Yellow Kid or Lyonel Feininger that was between painting and comics. But they were already bastards, they were already injected with pop. And they were all outside. In France they didn’t accept the French impressionism in the Louvre. That is why they were brought in America and now France is buying them back. So the idea of some arts with the big “A” and with a small “a” it’s, for me, an inconceivable thought right now.

I think you have been very successful with your books. And I think you’ve managed to find an audience and get good critiques and really make strong first steps on your career. And I guess you could put your name next to other cartoonists who also represent a new voice with great potential for very long careers. Do you think you belong to a generation right now?

I don’t want to spoil your image but my books are a niche in the market. I may be well known in a certain circle and it’s good like that too. Of course I am part of a generation but I can’t see the outlines of this generation. There is one thing we did, like the Italian guys in comics, we said, Sstop with this digital coloring, let’s go back to other techniques that are exactly as contemporary as the digital.” I always say that watercolor or wash is as contemporary as the new version of Photoshop because you can just squeeze it and have it and reproduce it so I don’t see why it is old fashion. This use of color is maybe quite an Italian thing that is also appreciated in France. If it comes to themes, I don’t think I am old enough to have developed something very special. I think we’ll see maybe in the future if I leave a trace or not.

PG: Thank you, Manuele.