This year’s Lucca Comics & Games (October 28th - November 1st) was the first full edition of the festival in the COVID-19 Era. I will not say the Post-Pandemic Era, because COVID is still with us, as many experienced after the festival.

This was the 56th edition of Lucca Comics & Games, which was first held in the city in 1966 (at which time it was called Salone Internazionale dei Comics), and in its its long history it has seen only one interruption, in the year 1988 (for economic reasons). Due to the pandemic, the 2020 festival was a “digital edition”; a smaller calendar of events also took place in the city of Lucca, and several comic shops around Italy promoted in-store events that were called “campfires”, a brilliant way to engage other entities in different parts of the whole. I didn’t attend the 2020 events in Lucca. That was not an easy choice, after visiting the festival for more than 20 years straight, starting as a young comic fan—the very first time my father took me there is still so vivid in my mind—and then with friends, and in the years after as a professional, just like now.

The 2021 edition had a lower profile; only 100,000 tickets were made available for four days of events, and they sold out in just one week. Big events in Italy at that time were accessible only by showing the “Green Pass”, a government certification to prove vaccination or a recent negative test. The festival was attended by 90,000 people; apparently not all the purchased tickets were used.

This time it was a whole different thing. In 2022, Lucca Comics & Games broke the 2019 record of 270,003 tickets sold with a total amount of 319,926 tickets sold; by October 17, the Saturday and Sunday events were sold out.

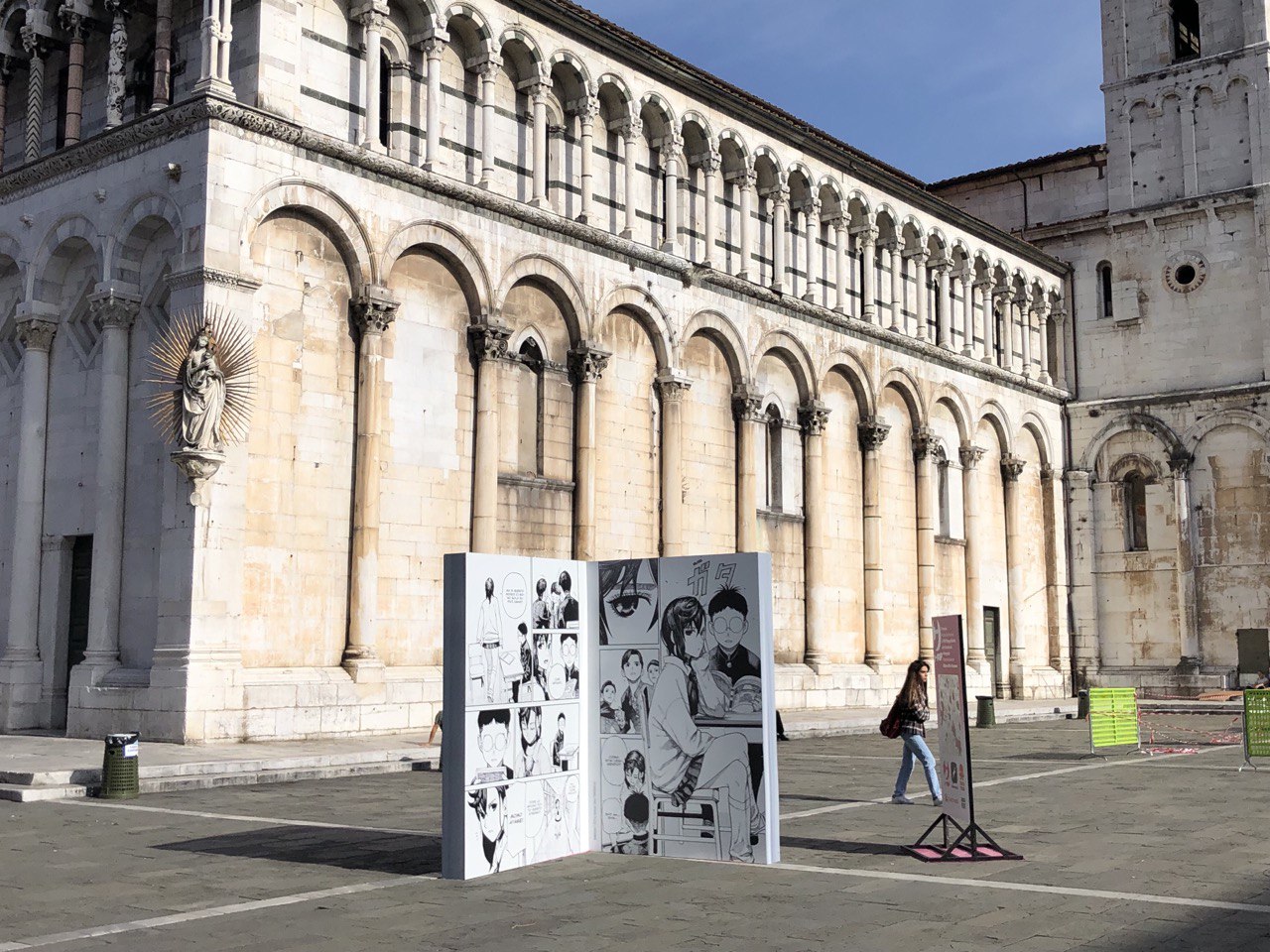

Those who are accustomed to visit international comic conventions should bear in mind that Lucca's can be totally different from other festivals; it is vaguely comparable to Angoulême, from an American perspective (the old small city, pavilions in the street, etc.), yet Lucca is still a very different and larger event. To get an idea of how impossible it is to quantify the number of people who flock into the city for the festival, just remember that not all the cosplayers you see parading in the streets have to buy a ticket, as many activities curated by the festival are free, especially those for kids. Many other people come to the city just to walk around its gorgeous streets and alleyways, enjoying (really?) the festive crowd during the Halloween weekend.

Lucca is a medieval city in northwest Tuscany, surrounded by ancient walls. The city’s population is less then 90,000 (which is to say, roughly equal to last year’s number of paying festival attendees). During the festival, Lucca’s (very) narrow streets are constantly packed with people - so many that it takes minutes to walk just a few meters' distance.

Lucca is a gorgeous city, and to quietly enjoy its beauty I’ve learned to get there on the day before the festival starts. Well, actually I do that mostly to avoid the pain of reaching the city amidst the chaos of the first day (trains packed with people, jammed roads). And I highly recommend the same to anybody who plans on attending the festival in the future. In my first walk through the city, I watch the pavilions finally take form a few hours before the opening, as workers are still unloading pallets of books; I can take time to say hello to colleagues and publishers before the storm arrives. But first of all, and most importantly, my very first stop is Polleria Volpi, a traditional grocery store where I buy my favorite choice for merenda in Lucca: schiacciata with biroldo. (Schiacciata is the Tuscan name for focaccia, and biroldo is a blood salami, a Lucca specialty - the name of which, as my friend the British cartoonist Richard Short remarked, “sounds like a Shakespearean clown.”)

I work for the web magazine Fumettologica, and for several publishers as an editor and translator. Therefore, from the first day to the last, this year just like recent years, I spent my time around Piazza Napoleone (the main city square) and the other squares and streets surrounding it, where all comics publishers have their booths and stands. I attended panels—sometimes I host one or two—and spent some time behind the table of a publisher (Edizioni BD), assisting authors whose books I curated.

Honestly, I have no idea what happens in the “Games” section of Lucca Comics & Games. I stepped inside that area—located right outside the city walls—only once, years ago, maybe by mistake (sorry, I’m not a fan). A couple of miles outside the city there is also a Japan-themed section of the festival; I haven’t seen that either, as I'm not attracted enough by its toys, collectables and food. I didn't watch the preview of the anime movie One Piece Film: Red, I didn't attend the premier of the horror movie Dampyr (based on a Sergio Bonelli Editore character) - I didn't seen or do so many things, because you just can’t see everything Lucca has to offer. And you simply don’t have to. In recent years the festival has grown mature, and its nature and core is not just about comics anymore.

Foreign guests were finally back: John Romita Jr. (generous with interviewers and fans) and James Tynion IV (a humble and devoted writer who met long lines of fans) from the USA; Yoshitaka Amano, Nagabe, Norihiro Yagi and Atsushi Ōkubo from Japan; Marcello Quintanilha from Spain (where he has lived since 2002); and several others, not counting actors and movie directors (Tim Burton was there). For Italian maestros and big names, Lucca is never to be missed; you could meet Milo Manara and Tanino Liberatore, while Igort, Gipi, Zerocalcare, Paolo Bacilieri, Fumettibrutti, Silvia Ziche and Manuele Fior (just to name a few you should know) were there to present their new books.

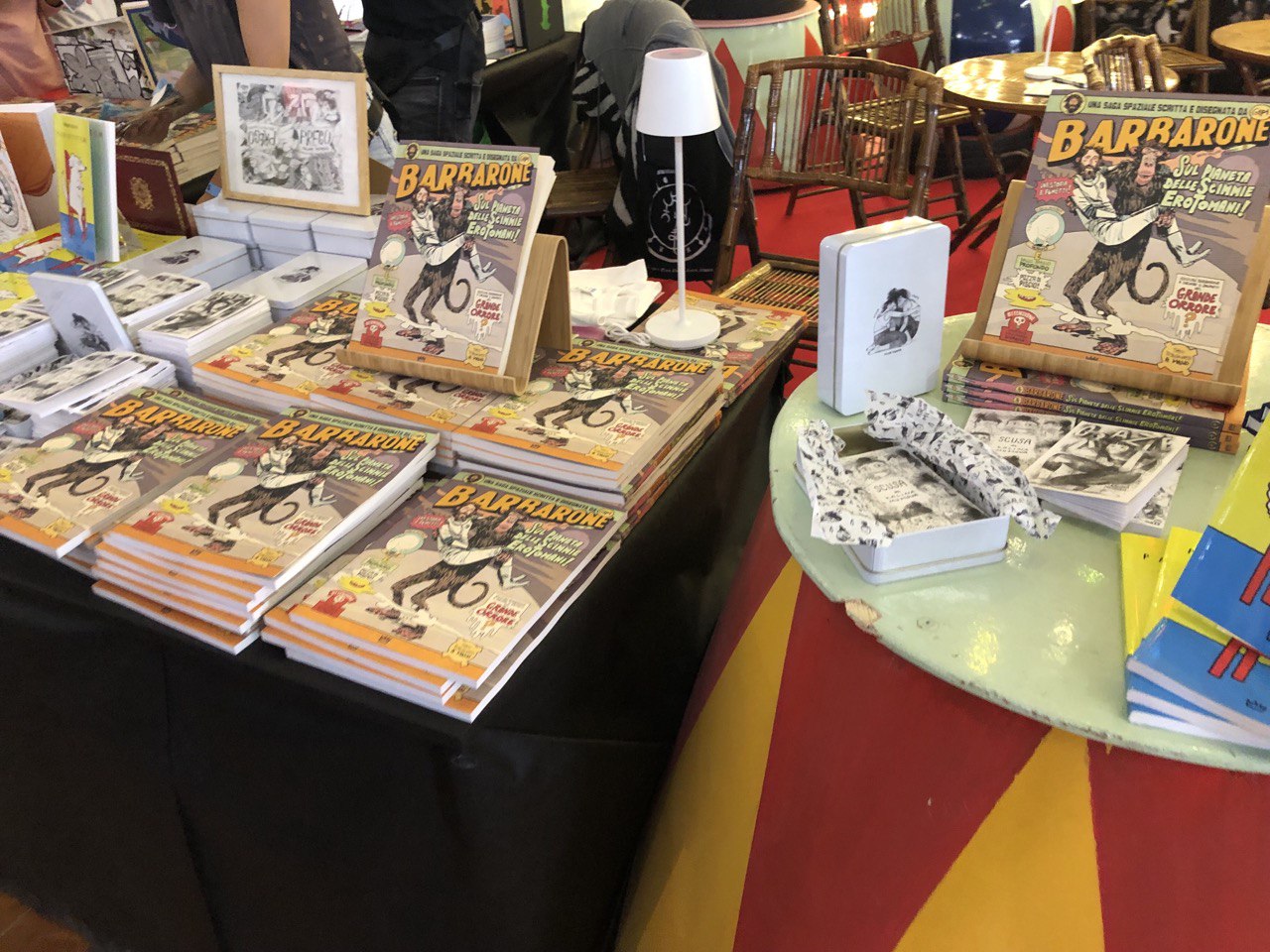

Igort’s Oblomov Edizioni just released the second instalment of his Ukrainian Notebook (to learn more about it, read the interview he gave me last summer). Gipi was there with the small publisher Rulez, managed by his wife, Chiara Palmieri, who did an amazing job setting up a gorgeous stand with flashing colors and lights. She brought three books: Gipi’s Barbarone sul pianeta delle scimmie erotomani (“Barbarone On the Planet of Erotomaniac Monkeys”), a crazy and super-funny sci-fi story (first book of a trilogy); the strip collection Paniktotem by German artist Nadine Redlich; and Isa by Lorenzo Ghetti & Rita Petruccioli, a funny and intelligent Instagram strip whose character is a noble woman from the Renaissance.

Among other new titles, Coconino Press brought Hypericon, Manuele Fior’s new work after his astounding Celestia from 2020. I haven’t read Hypericon yet, but it looks stunning and little less fantasy-oriented than Celestia (a book I widely explored in an interview with Manuele earlier this year).

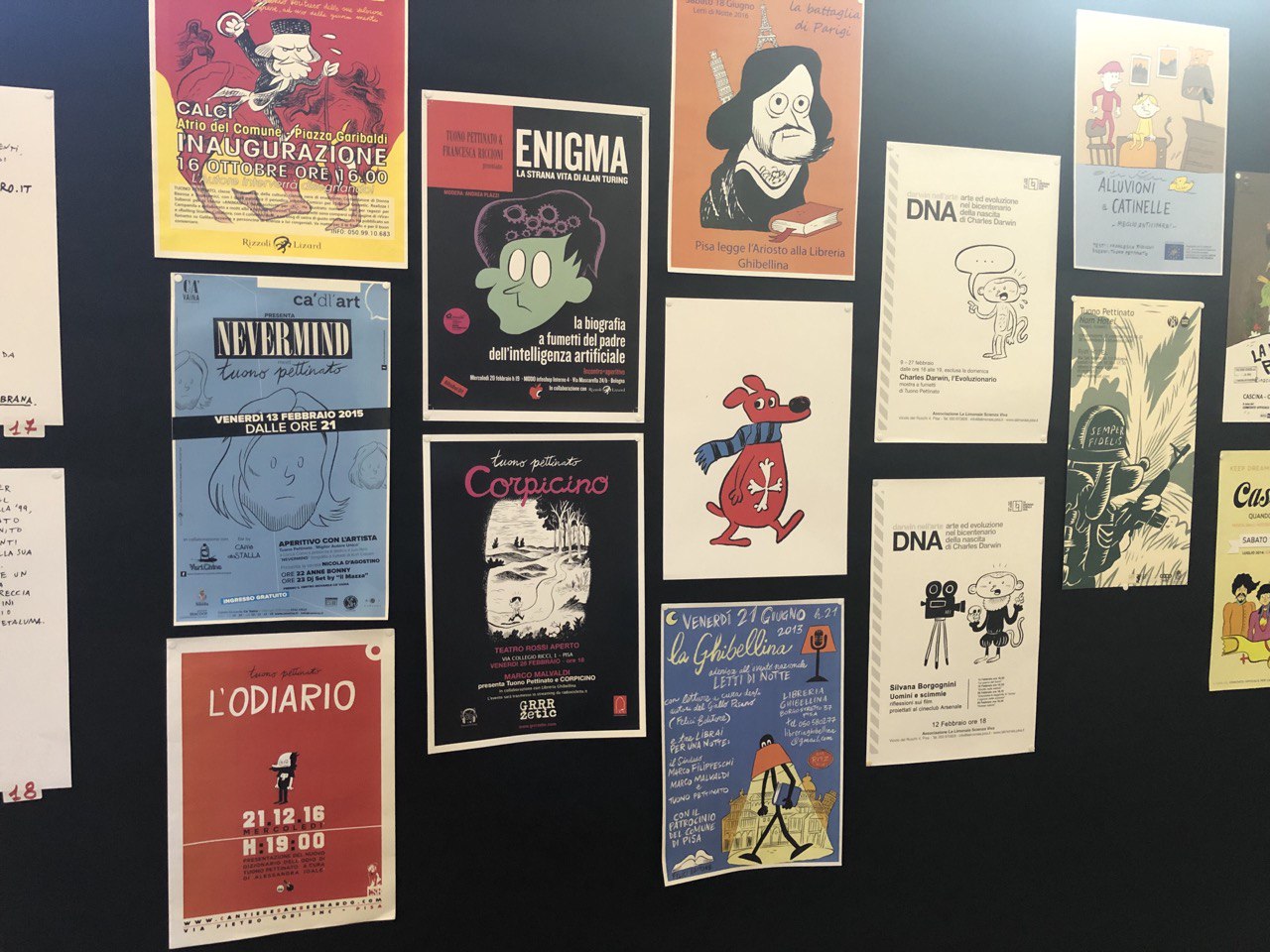

I experienced a great emotional moment when I visited the “Self Area”. This section is in a courtyard next to (obviously) a church, where, with admission free for visitors, DIY and self-publishing collectives are located. This year, the area was dedicated to the memory of Tuono Pettinato (if you still don’t know who the greatest Italian cartoonist of the last two decades was, check out my profile of him from last year). The newly established Tuono Pettinato Foundation was there to present the anthology Hobby Comics 7, containing comics from all members of the Super Amici collective, including Pettinato. A wall was dedicated to photos, posters, and Tuono's art. Lots of artists stopped there to pay homage, from Milo Manara to Zerocalcare.

It would be an impossible task to speak of all the many new books at the festival. For the Italian comics market, Lucca Comics and the autumn season are the hottest days of the year, both for quality and quantity of production. And after two years of COVID, at the end of 2022 we are starting to see the biggest names coming back to the business. Besides all the new books and the guests, what makes Lucca so crucial is that the event is where publishers announce all their new releases and plans for the months to follow.

Speaking with editors from several publishing companies—and also by simply walking around pavilions and city streets—the impression I got is that enjoying the festival this year clearly wasn’t as easy as last year, but fans came and went with great interest... and great patience as well. All the pavilions had long lines for the whole day; those where Japanese artists held signing sessions saw young fans spend the night outside (not a bad choice, considering how hard it is to find accommodations). In Italy, we are living a time when graphic novels and new volumes of manga series are often among the weekly top ten bestselling books. A popular artist like Zerocalcare—a stable presence among such lists every time Bao Publishing releases a new book of his (exactly once a year, from 10 years ago, right before the Lucca festival)—has seen his most recent graphic novels land at the very top on their first week of release.

I visited most of the pavilions during the first and the last day: the less crowded ones, those I would recommend to a casual visitor. The festival is too big; it’s huge. By its numbers, it is by far the biggest comic event in Europe, and the second in the whole world, after Japan’s Comiket. The city is too small to contain it and its visitors. But don’t ever think of moving this festival to a different city; after over 50 years, Lucca and Comics are two words that go hand in hand, a stable tradition.

While all of the booths, stands and stores are contained in temporary pavilions at Lucca, the various panels, conferences and public interviews with artists take place mostly in deconsecrated churches or conference halls owned by banks and foundations.

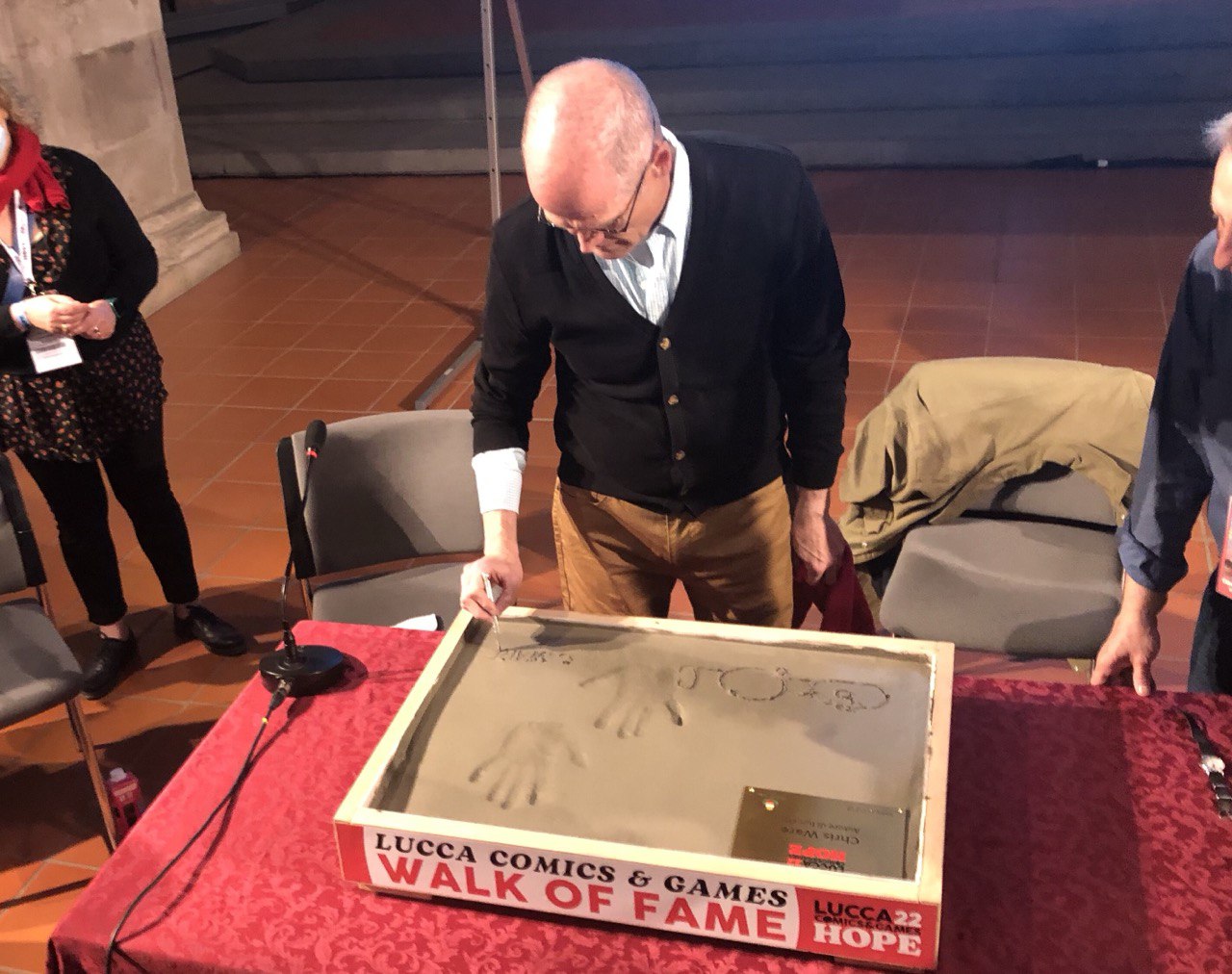

I saw Chris Ware interviewed in a huge church, speaking with journalist Luca Valtorta from the national newspaper la Repubblica and novelist Francesco Pacifico (a funny and smart presence), who has translated Ware’s books to Italian. Following a recent Lucca tradition, before the interview Ware was requested to sign a concrete plate where he’d impressed his hands.

This “ceremony” always looks kinda awkward, as you can see in the picture above. Ware expressed delight at how comic artists are respected in Europe, clearly pleased to see a large audience of non-cartoonists (he asked for a show of hands and only eight comic artists were there) inside such a big crowded church. Yet I do not enjoy when cartoonists are asked how they manage their time and how their life was during lockdown, so I am quite jealous of those who had the chance to see Ware a couple of days after the festival, in Milan, interviewed by Italian cartoonist Paolo Bacilieri at the ADI Design Museum. I was told the conversation there was much more interesting and passionate.

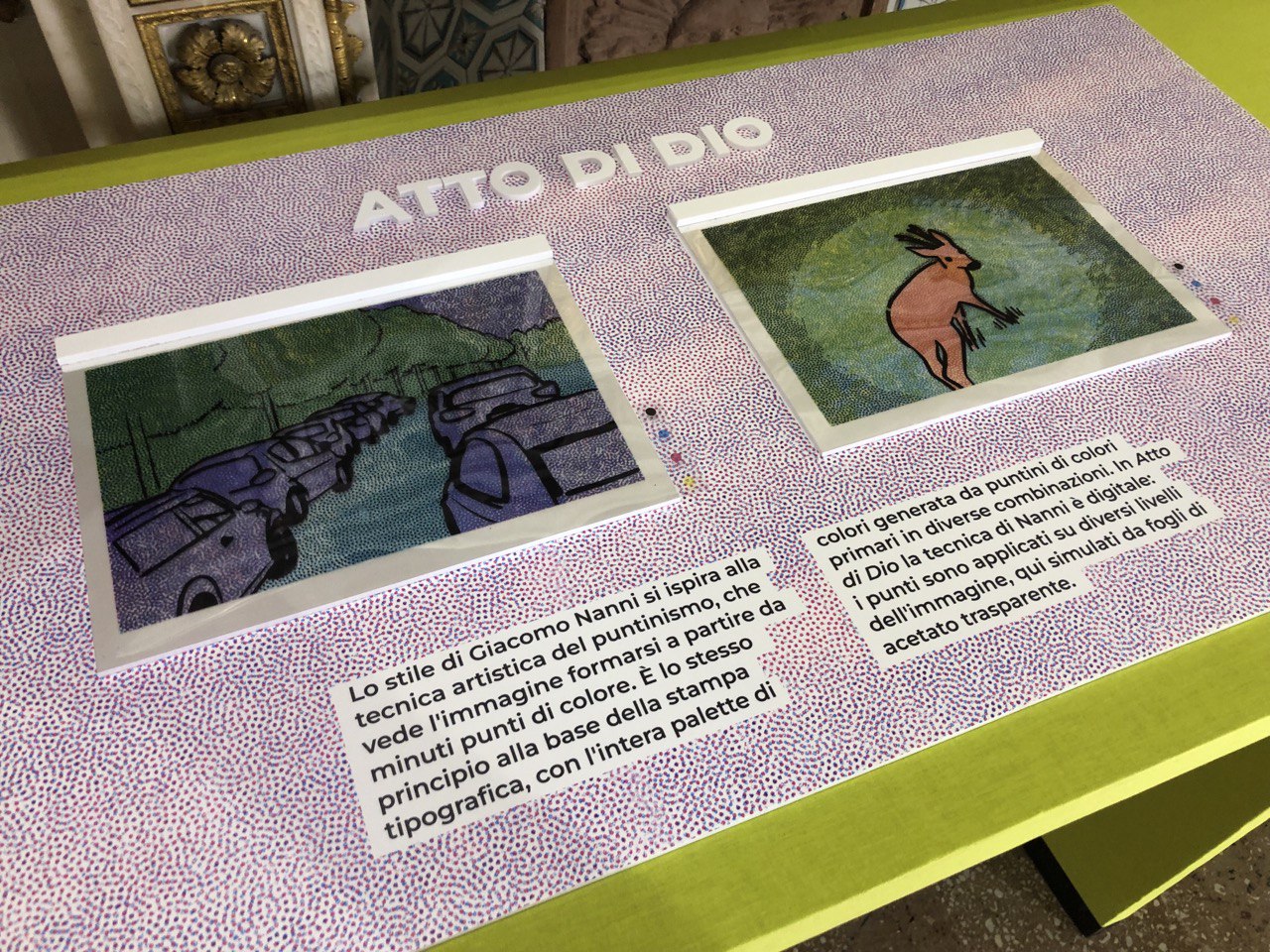

This year’s main exhibitions included: separately, Chris Riddell and Ted Nasmith (I sincerely apologize for my ignorance, but I find it hard to distinguish these types of traditional fantasy illustration); Mirka Andolfo (lots of printed comics pages and, at least, a cool setup); Atsushi Ōkubo (very few pages, another cool setup); Giacomo Nanni (I recommend reading Matteo Gaspari's profile of him; Giacomo is one of the most intense and creative Italian artists working today); and Alfredo Castelli & friends (Castelli is a pivotal figure of Italian comics, the beloved creator of many characters in career spanning more than 50 years, famous for the series Martin Mystére published by Sergio Bonelli Editore).

Lucca also has its own festival awards; the evening ceremony was hosted on Saturday the 29th at the Teatro del Giglio. The webtoon The Hellbound, by Yeon Sang-ho & Choi Gyu-seok, in print from Panini Comics, won Comic of the Year (despite being a series, for which there is a separate award, insert shrug emoji); Gaëlle Geniller won Best Artist for Le Jardin, Paris from Star Comics (this one passed me unnoticed); R. Kikuo Johnson won Best Writer for No One Else, released in Italy by Coconino Press; (well deserved, should have won Comic of the Year); Kafkaesque by Peter Kuper, released in Italy by Tunué Edizioni, won Best Short Story or Anthology; Cosma & Mito, by Nicola Zurlo & Vincenzo Filosa, from Coconino Press, won Best Series; La Revue Dessinée Italia (a graphic journalism project published by La Revue Dessinée Italia itself) and Comics & Science (an educational collection from CNR Edizioni/Feltrinelli Comics) both won Best Editorial Initiative; Giorgia Kelley won Best Newcomer for Strange Rage, published by Rizzoli Lizard; Monsters by Barry Windsor-Smith, released in Italy under Mondadori's Oscar INK label, won the Special Jury Prize; Paco Roca won Author of the Year for Ritorno all’Eden, published by Tunué Edizioni; and Riyoko Ikeda & Milo Manara were named Masters of Comics (their self-portraits will now be included in the comic artist portraits collection at the Galleria degli Uffizi).

Until a couple of years ago, I’d enjoyed attending the ceremony, for a naïve thrill of suspense, and genuine love of the medium. But the whole thing is too long and boring - and besides, games are awarded before comics. I regret missing a few funny and cringe moments I’ve since heard about (everybody was talking about Manuele Fior being called Michele Fior by the hosts), but I’d rather spend that time having a drink and looking for a place to get dinner. And that’s not an easy task at all. Before dinner, the place to have an aperitif with comic artists is the Caffè del Mercato in Piazza San Michele, where you get the Peschino, a drink I think is made with prosecco, vodka and peaches in syrup. Then, the place where everyone in the industry, and every—I mean every—cartoonist goes to get drunk after dinner is Piazza Anfiteatro, a beautiful oval-shaped piazza full of bars. I don’t think there are any comics fans there at night; only people from the industry and Lucca natives.

October of 2022 has been the hottest October since 1800 in Italy. I think I have never seen a Lucca festival without at least one rainy day, which is never comfortable when you have to walk from one pavilion to another in streets packed with people carrying their paper goods. Although this year it felt like the festival was moved to July, one way or another it is still that time of the year when winter’s chilling breath starts to blow on your neck. I have never been to Lucca Comics without bringing home an annoying cold.

You’ve noticed from my pictures that very few people were wearing a mask. Guess who got COVID? Yes, I escaped a group of Fascists—it’s not even a long story; a cartoonist friend from Lucca is on their blacklist, and while I was walking with him we managed to escape in Piazza San Michele, unfortunately missing our daily dose of Peschino—yet I didn’t escape COVID. Nothing serious, I tested negative the day I wrote this line. See you next year in Lucca.