Joe Giella, whose artistry defined the Silver Age of DC Comics, has passed away at the age of 94.

Giella, the son of Italian immigrants, was born and raised in New York, and grew up in Astoria, Queens, alongside his four younger siblings. Among his closest childhood friends was an outgoing youngster named Anthony Benedetto, who would go on to international superstardom as crooner Tony Bennett. Giella’s own creative aspirations and admiration for comic strips, including Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant and Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon, inspired his interest in the visual arts and led him to Manhattan’s prestigious School of Industrial Art, where he would study alongside Benedetto (himself a talented visual artist), as well as classmates Al Scaduto, Sy Barry and Emilio Squeglio, all of whom would enjoy long, prolific careers in the comics business.

“Joe told me that the original building they attended dated back to the Civil War and hadn’t been updated since,” says illustrator Adrian Sinnott. “He, Sy and Al were in the boys’ room where Sy was smoking. Someone told them that a teacher was coming and Sy flicked the cigarette butt over the door of one of the stalls, thinking they could get away with it if they weren’t caught with the cigarette. The teacher came in and was giving them what for when these shouts of pain came from the stall and Emilio came flying out. The cigarette had gone down his pants. And that’s how they met Emilio.”

Students at the School of Industrial Art learned illustration from top professional artists, including Hungarian illustrator Willy Pogany, whose lessons made a big impression on Giella. “Almost everyone in Joe’s family was either police or firemen,” says Sinnott. “Joe’s dad couldn’t imagine him making a living from drawing. But one of Joe’s teachers was adamant and said he had a real future. Thank goodness for that teacher!”

To offer financial support to both his parents and his younger siblings, Giella left high school at age 17 to earn a living as a visual artist, and launched his career at Hillman Periodicals with “Captain Codfish”, a lighthearted comic story that appeared in the 10th issue of Punch and Judy Comics in the spring of 1946. Determined to build on that success, Giella continued his education at the Art Students League in Manhattan, alongside future DC Comics artists Joe Kubert and Mike Sekowsky. “An interesting thing about Sekowsky was that during one class the teacher came around to look at our work and stopped at Mike’s,” Giella recalled in an interview with historian Tim Lasiuta. “Instead of drawing the model, he had drawn a comic-book figure which drew the ire of the teacher. Mike never came back to class.”

Unable to keep up with the cost of tuition, Giella left the Art Students League and relied on second-hand anatomy books to further his education and artistic skills. Already tired of the unreliable nature of freelance work, he parlayed his comics portfolio into steady work as an inker on Captain Marvel stories for Fawcett Comics, embellishing the penciled art of Pete Costanza and Captain Marvel’s co-creator, C.C. Beck. That assignment, and a personal recommendation from Sekowsky, led to freelance work and eventually a staff position at Marvel precursor Timely Comics, inking their top three superhero characters: Captain America, the Sub-Mariner, and the Human Torch. “I would do anything they offered,” Giella recalled to Lasiuta. “Touch-up work, background art, inking, or redrawing. Because of this, I decided to focus on inking instead of penciling...

“When I started at Timely I was earning $60 a week and by the time I finished there and moved to DC, I was up to $90. That was one of the motivations for me to become an inker rather than a penciller as it was easier to ink more pages per day than pencil them.”

Giella almost failed his Timely audition, however, when the excited young artist accidentally left his tryout pages, drawn by Sekowsky, on a subway train. Editor Stan Lee chewed out the young artist, but Sekowsky intervened and offered to redraw the pages, which Giella inked in record time. Lee was impressed by the artist’s speed and skill, and Giella secured a place in Timely’s bullpen.

By the late 1940s, as superheroes fell out of fashion at Timely, Giella moved on to the publisher’s teen and romance titles, including Patsy Walker, Nellie the Nurse and Millie the Model, paired with Sekowsky and Stan Goldberg, among others. It was during his tenure at Timely that Giella met artist Frank Giacoia, who would become one of his closest friends and artistic partners, and would even serve as best man when Giella married Shirley Pierrepoint in July 1952.

It was Giacoia who introduced Giella to the editors at National Periodical Publications/DC Comics in 1949, where he was hired on the spot as an inker on superhero titles like Flash Comics, including the first appearance of the Black Canary, written by Robert Kanigher and penciled by Carmine Infantino. Editor Julie Schwartz often paired Giella with Infantino on superhero titles, and—as DC diversified its early '50s output—on western features like "The Trigger Twins", "Pow-Wow Smith" and "Sierra Smith", where Giella inked Infantino and other top illustrators including Gil Kane and Alex Toth.

“Joe was an all-around artist but editors more often gave him inking work… and he was not the kind of inker who'd trace the penciler's work slavishly,” historian Mark Evanier noted in a recent blog post memorializing Giella. “With his editors' permission (and sometimes without) he would interpret pencil art and add in or omit elements that the first artist drew. Some objected but his editors usually thought he'd improved the work so they always kept him busy.”

Reliable and fast with the brush, Giella was able to supplement his DC Comics workload with other freelance work, assisting on several daily comic strips in the 1950s and early 1960s, including Sherlock Holmes and Johnny Reb with Frank Giacoia, and Flash Gordon with Dan Barry. “Julie Schwartz loved his work, his work ethic, and the fact that he was always on time,” observes Joe’s son, Frank Giella. “Julie would say he could set his watch on Joe.”

During this incredibly prolific period for Giella’s artistry, he spent a combined eight years of active and inactive duty in the United States Naval Reserve, having enlisted during the Korean War. He was very proud of his service, and listed it prominently on his cartoonist bio for the entirety of his professional career.

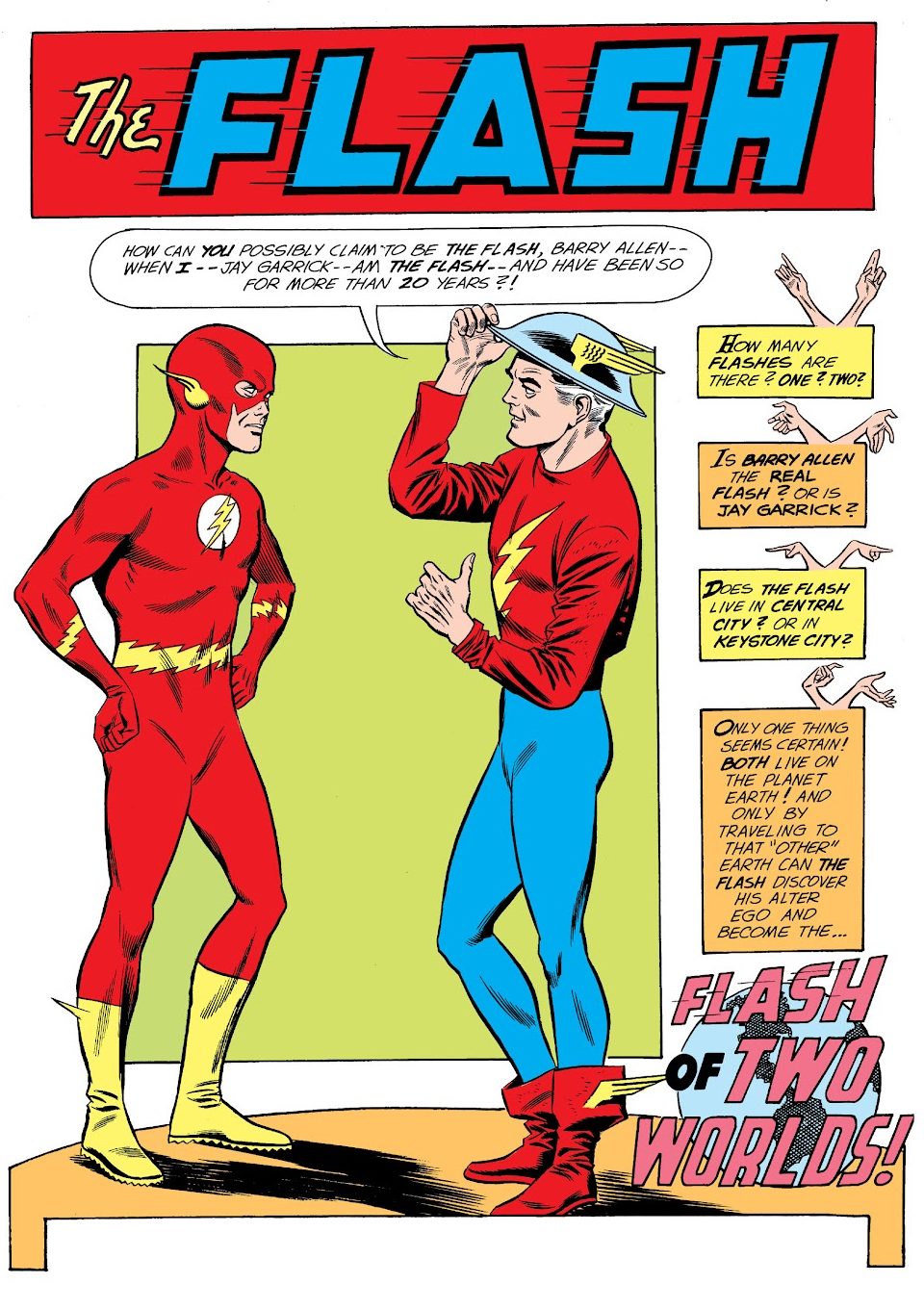

As DC further experimented with new genres and formats in the early 1950s, Giella became the go-to inker on romance comics and science fiction, including the 1951 first issue of the anthology series Mystery in Space. But it was the resurgence of superheroes, with the introduction of Barry Allen as the Flash in the pages of Showcase #4 in 1956, that would alter the course of Giella’s career and that of the entire comic book industry. The success of the Flash feature in Showcase prompted a full-scale superhero revival that would come to be known as the Silver Age of American comic books, with updated versions of DC heroes like Flash and Green Lantern leading the way.

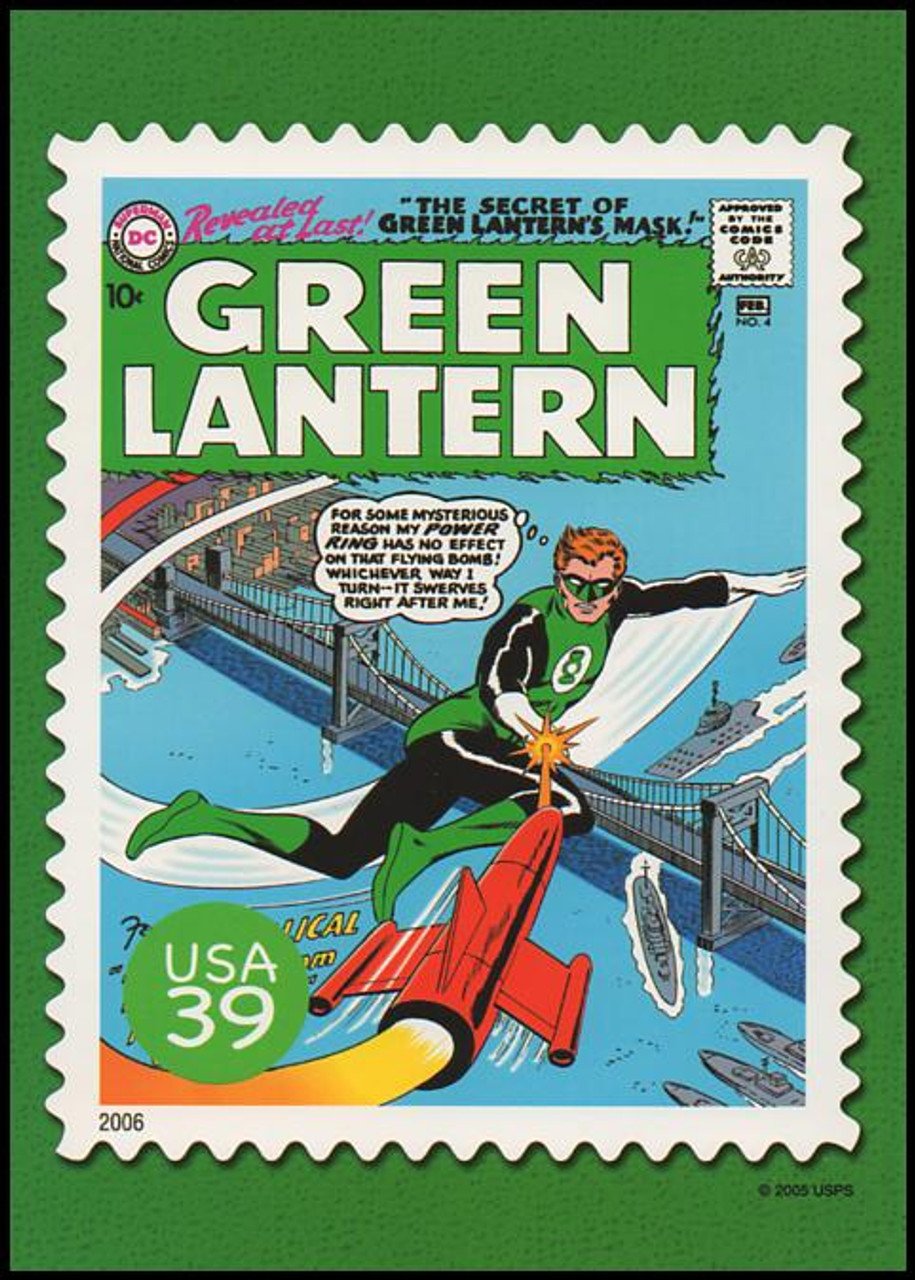

Giella’s polished, professional style made him an ideal choice to ink Carmine Infantino on Flash’s solo title, which launched in 1959, and Gil Kane on Green Lantern’s solo title, which followed in 1960. “What’s important to understand is that Julie Schwartz, not blessed with an artistic eye, relied heavily on a cadre of slick inkers to provide a house style for his books,” observes former DC Comics editor Bob Greenberger. “Joe was a workhorse along with Bernard Sachs, as well as Frank Giacoia, who was slow as molasses, Sid Greene, and Murphy Anderson. Joe could be relied on to fix artistic errors or make up lost time.”

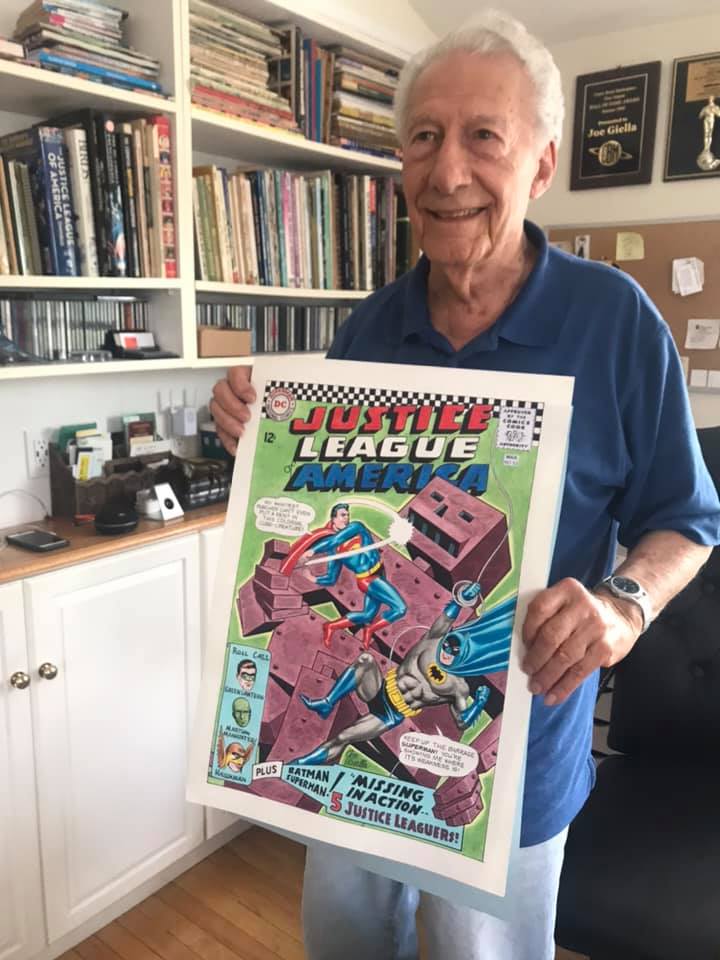

Among other milestones of the Silver Age, Giella inked the earliest stories featuring sci-fi hero Adam Strange in Showcase and Mystery in Space, and is one of three inkers credited, alongside Bernard Sachs and Murphy Anderson, on the story that introduced the Justice League of America in 1960’s The Brave and the Bold #28. “As a reader,” former DC Comics President and Publisher Paul Levitz remarked on Facebook, “I knew his work from the Silver Age DC titles, where [Giella] often inked challenging pencillers from Carmine Infantino to Mike Sekowsky to Gil Kane, (challenging because of their varied styles and that they stimied some inkers who couldn't interpret their work effectively), serving as one of the most consistent styles in Julie Schwartz's titles.”

Comic book writer and inker Al Gordon, who grew up during the Silver Age, agrees. “Joe was the perfect inker for Carmine during that era. I inked Carmine when I first started out, and his stuff is not easy to ink, at all. Some figures were half-finished, some were really sketchy, he just drew a mile a minute. You had to look at his pages and figure out which lines were the best to ink. You see Flash showing up a dozen times on a page, and have to figure out how to capture the motion in each one of them, and Joe did that better than anybody.”

“He was the cornerstone of '60s DC,” Gordon continues. “As a kid, before there were any Marvel superheroes, Flash and Green Lantern were my favorites. Joe Giella and Frank Giacoia were so prolific in the Silver Age, and really established the look of those books. The unspoken heroes of that era, who never got the credit they deserved. You breathed a sigh of relief when you opened a book in the '60s and saw that Joe was the inker.”

When Julie Schwartz was tasked with modernizing Batman in the mid 1960s, the character’s solo titles, Batman and Detective Comics, had weathered a prolonged sales slump and were on the verge of cancellation. The Batman titles published in 1963 were virtually indistinguishable from those published a decade earlier, and the Gotham Guardian’s adventures seemed stodgy and old-fashioned when compared to the rest of DC’s Silver Age output. At this critical moment, Schwartz assigned the writing on these titles to John Broome and Gardner Fox, architects of DC’s recent superhero hits, while the art duties went to Carmine Infantino, who had turned the Flash into one of DC’s best-selling characters, and Sheldon Moldoff, who had worked as a ghost artist on Batman comics since 1953.

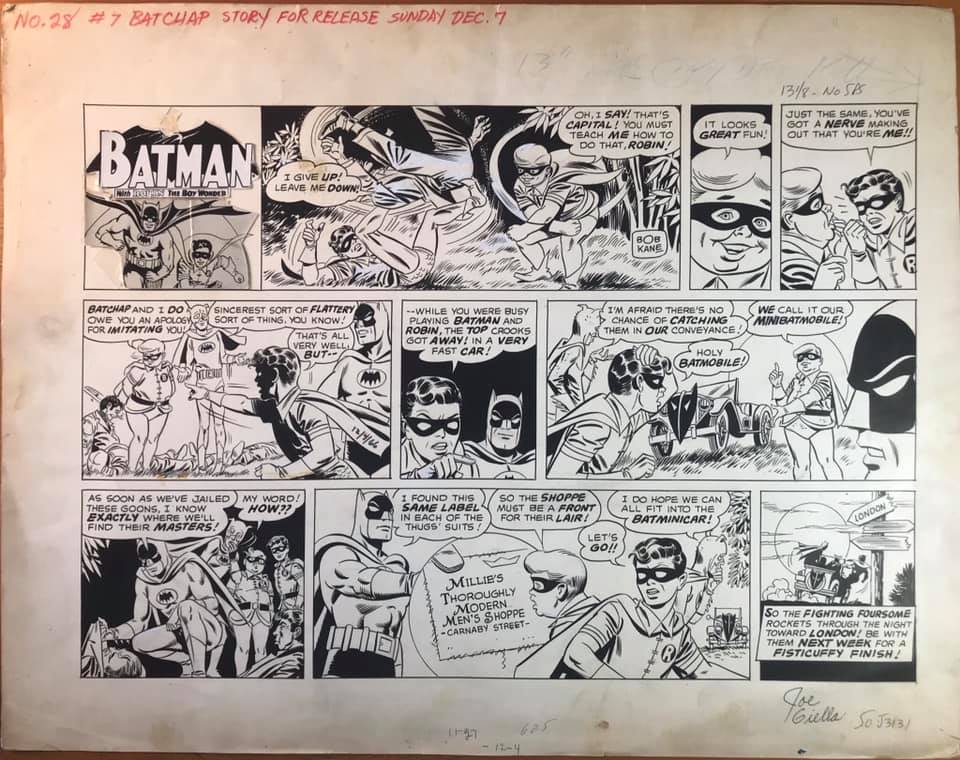

Giella was assigned to ink both artists, creating a visually consistent “New Look” for Batman and Detective, which brought the comics in line with the rest of DC’s 1964 titles. “[Giella] was especially valuable in [the '60s] when DC wanted a more realistic look to art on Batman comics that Bob Kane allegedly drew,” Mark Evanier observed on his site. “Sheldon Moldoff, who ghosted for Kane, couldn't give them the look they wanted when he penciled those stories. Joe supplied it in the inks.”

The New Look was a sales success, and the steadily improving sales on the Batman titles saved those books from cancellation. The Giella-inked May 1965 issue of Batman, featuring the return of then-obscure Golden Age villain the Riddler, was adapted into the debut episode of the Batman television series in January 1966, and soon “Batmania” swept the nation, as the top-rated ABC show became a pop-culture sensation. Sales on the Batman comic books skyrocketed, sales of comic books increased across the board, and the buying public couldn’t get enough of the Caped Crusader.

In May 1966, the Batman newspaper strip was revived after a long absence, and following a brief stint assisting Sheldon Moldoff, Giella was tapped to pencil and ink the daily and Sunday comic during its peak circulation, from the summer of 1966 through the spring of 1968. These storylines pitted the Dynamic Duo against the likes of the Joker and the Penguin, and introduced Barbara Gordon, aka Batgirl, to the daily comics. Although this assignment came with higher pay and more prestige than his comic book work, the Batman strip was signed “Bob Kane”, whose contract with DC ensured him sole credit on all Batman comics published from 1939 until the late 1960s.

“Once Julie retired in 1985, Joe had little reason to come up to the offices, so we only saw him at conventions,” notes Bob Greenberger, whose tenure at DC started as Schwartz’s was winding down. “His candor about ghosting for Bob Kane in comics and on television helped peel away the mystique Kane spent the first few decades of Batman perfecting. He seemed to be one of the few to get along with Kane, his demeanor unruffled by Kane’s ego.”

“Joe Giella was a superstar and one of the last of the DC legendary artists who spanned the Golden Age to the modern era,” notes Batman movie producer Michael Uslan. “He was the oldest Batman artist and his impact on the Caped Crusader is incalculable.”

While producing the Batman newspaper strip and continuing to freelance for DC Comics, Giella wrote and drew a daily panel called Character Clues, which was distributed by the Ledger Syndicate from 1966 to 1967. But Batmania soon wound down, ratings for the television series plummeted, and circulation on the strip rapidly declined; by the end of 1968, Giella has returned to more-or-less full-time work as a DC Comics inker. His contract permitted him to pursue work outside the publisher so long as it did not interfere with his DC obligations, allowing Giella to assist Sy Barry on the long-lived newspaper strip The Phantom, which he did three days a week for 17 years, and to illustrate a pair of novelty books featuring Marvel Comics characters for Simon & Schuster in the mid '70s: The Mighty Marvel Comics Strength and Fitness Book and The Mighty Marvel Superheroes’ Cookbook.

Giella continued to work for DC Comics until the early 1980s, when a diminishing workload led to his decision to step away from monthly comics and try his hand at commercial art. “As an editor, and even more as the guy who was managing deadlines at DC for some years in the late 1970s, I knew him as a problem solver,” recalled Levitz on his Facebook page, of his working relationship with Giella during the artist’s final years at DC. “Whatever the difficulty, whatever the deadline, Joe was calmly willing to step in and make sure the end result was produced professionally. He was one of the quiet stalwarts who kept things going.”

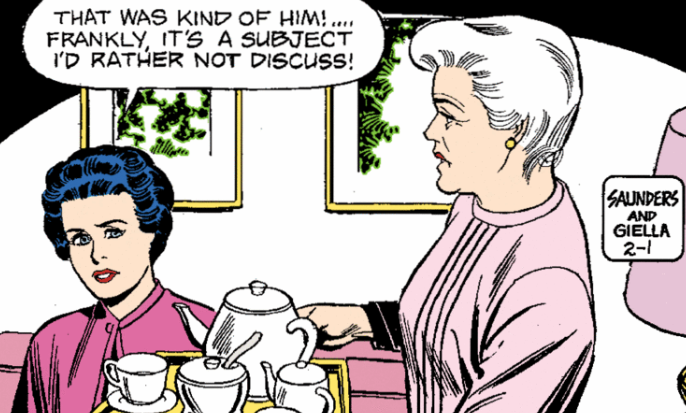

He spent the majority of the 1980s as a commercial artist, drawing advertisements and illustrations for clients including McCann Erickson, Saatchi & Saatchi, and Doubleday Publishing, among others. But Giella could never resist the pull of comics for very long, and upon his “retirement” in 1991, at the age of 63, he took over as the artist of the Mary Worth newspaper strip, written by John Saunders, whose father Allen Saunders had launched the strip with artist Dale Conner in 1938.

“I got a call from King Features. I was a little confused as to why,” Giella told Mark Schwed of the Palm Beach Post in a 2006 article. “But after a while, I got into it. I could see why people really like this strip. It's like a cult out there.” When asked about the difference between Mary Worth and his extensive superhero work, Giella remarked, “[w]ith superheroes, it's mostly action. Everything is exaggerated. With Mary, it's kind of a low-key soap opera. You have to try to create interest with expressions. A look on her face. Very rarely does anybody throw a punch.”

When John Saunders passed away in 2003, Karen Moy of King Features stepped in as the new Mary Worth writer, and could not have found a more welcoming creative partner than Giella. “I met Joe several times before I worked on Mary Worth with him. I liked him right away,” says Moy. “He struck me as a down-to-earth gentleman who treated others with real consideration, very old school, similar to Lee Falk. It wasn't until I started working with him on Mary Worth in 2003 that I got to know him better and realized how incredible he was.”

“Through my years of working with him we'd talk every week on the phone, not just about work, but also about life,” Moy continues. “I appreciated the wisdom of his experience, but moreover that he cared about what was going on in my life. His viewpoint was usually spot on. It was easy to talk to him because he was straight with me and still kind. He had a strength and toughness about him that was based on deep moral integrity and a sense of responsibility.”

Because of their proximity to each other, Moy and Giella were able to socialize with other cartoonists at events in and around New York City, including the annual “Bunny Bash” hosted by The Lockhorns writer Bunny Hoest at her Long Island home. “Many times Joe would give me a lift over to [Bunny’s] party,” Moy recalls. “We'd discuss Mary Worth scripts in his car on the scenic drive over. I loved his anecdotes and stories. We had some laughs along the way. I learned a lot from Joe and will always think of him as one of the greats.”

The always-sociable Giella was a member in good standing of the Long Island chapter of the National Cartoonists Society, affectionately known as the Berndt Toast Gang - named in honor of cartoonist Walter Berndt, creator of the comic strip Smitty, who in 1966 initiated regular meetings among Long Island-based cartoonists and animators. “To be honest, I didn’t know Joe well,” recalls cartoonist Ed Steckley. “I’d see him and catch up at the occasional Berndt Toast meeting, but, what struck me about Joe is this. As a younger member of the NCS, and after only seeing him maybe once every six months, Joe always remembered my name, and he always remembered what we’d talked about the previous time.

“I was always struck by how he treated me as an equal. He didn’t know my work at all, but upon hearing that I was ‘an artist’, it was kinda like he took my word for it, and treated me as a colleague, rather than a fanboy.”

Another “fanboy” from the Berndt Toast Gang was Greg Fox, creator of the comic strip Kyle's Bed & Breakfast, who worked as Giella’s assistant on Mary Worth from 2008 until his retirement in 2016. “I'd known Joe for a few years before going to work for him, but I was still a bit intimidated,” says Fox. “He was someone whose name I'd seen on comic book credits since I was a little kid. But he was wonderful and warm to work with. Not a bit of ego about him.”

“We bonded pretty immediately over the fact that we were both into health food. He was always sharing articles with me on this vitamin or that supplement, or the evils of sugar,” laughs Fox. “But I truly believe his healthy diet and lifestyle were a big factor in what enabled him to have that long, very productive career.

“And that work could be daunting. Producing a daily comic strip is relentless work. There's always another week's worth of strips to be completed. I know that kept Joe from making a huge amount of convention appearances, although I'm amazed at the number that he was able to make. How he fit those into his schedule, I'm not sure.”

Giella made room in his work schedule for a number of hobbies, including watching westerns on television and painting in a realistic, “not comic-like” style, according to Fox. “He didn’t get to do as much of that as he’d have liked, though, because he always had many requests for commissioned artwork from fans. Often there would be a long list of requests, and another one would come in, and he'd say, ‘I'll add you to the list.’ Sometimes, it would be a long wait, but he'd get through that list, eventually. He didn't want to disappoint anyone.

“Amazingly, he somehow found the time to do a number of drawings for various local charities that came calling. Gorgeous, often fully-colored poster-style pieces of Batman or the Joker or Green Lantern. He had no qualms about giving away these stellar works to charitable organizations, who I'm sure were thrilled to receive them.”

Giella's dedication to helping others was acknowledged by the Hero Initiative, which presented Giella with a lifetime achievement award in 2016. He earned many accolades later in his career, making up for the anonymity that he experienced during his years ghosting other cartoonists’ comic strips and inking comic books in an era when creative teams went largely uncredited. He received the Inkpot Award from Comic-Con International at their 1996 convention. In 2018, he was inducted into the Inkwell Awards' Joe Sinnott Hall of Fame, named for his longtime friend, in recognition for a lifetime of contributions to the comic book arts.

His proudest achievement, however, came in 2006, when the United States Postal Service issued a series of postage stamps commemorating the art and characters of DC Comics, including several images inked by Giella during the Silver Age. “My favorite memory of Joe is from San Diego Comic-Con, when we [hosted a panel celebrating] the Super Hero Stamps,” recalled Paul Levitz on Facebook. “Many of the contributing artists got to speak, but Joe's humility and humanity flowed out of him as he spoke, saying, ‘this is the best thing to happen in my life... except my wife, Shirley, of course.’ He could barely believe his art was going to grace a postage stamp.”

After 25 years of drawing Mary Worth, his “post-retirement” comic strip, Giella withdrew in 2016, and was succeeded by artist June Brigman. “I met Joe in 2016, when he handed me the reins of Mary Worth,” Brigman recalled on Facebook. “His lovely wife shook my hand and told me a very heartfelt, ‘thank you!’ At the age of 87, Joe was finally retiring. But let me tell you, he was a hard act to follow. Joe was a consummate professional and an excellent draftsman. He did exciting, dynamic superheroes as well as the endless repetition of a syndicated comic strip and always maintained a high standard of quality.”

Giella hardly slowed down in his final years, drawing, painting, maintaining an active social life with his cartoonist friends and connecting with his fans around the world. “I'm glad when he retired from Mary Worth that he finally could step away from strict syndication deadlines and travel to comic conventions, take on private commissions, and work on personal projects,” notes Karen Moy. “Always busy but without being chained to the syndication deadline drawing board. He deserved that personal time.”

And Giella spent as much of that personal time as possible in the company of his wife, Shirley, their four children, ten grandchildren, and their great-grandchildren. “What really sustained him was his family,” says Greg Fox. “His loving and very devoted wife Shirley, his kids and grandkids. They were often popping up in the studio, and he wasn't a sort of ‘hands-off’ type of artist. He'd let those grandkids come in and run rampage through the studio! Shirley would often ask me to stay for dinner after a days' work, and I'd gratefully accept.”

Giella produced a staggering amount of artwork over the course of his 70-year professional career, with more than 4,000 comic book stories to his credit; many of those classic Silver Age stories are still in print and thrilling readers today. His “second act” as a comic strip artist commenced while he was still very much in demand as a comic book inker, including 3 years of Batman, 17 years as an uncredited artist on The Phantom, and a quarter-century run on Mary Worth drawn at a point in his life when all of his colleagues were contemplating retirement.

But that prolific, era-defining artistry is only a small part of Giella’s legacy. “Everything he drew, it was all with a gentle, clean line that produced likable people - the way Joe saw the world,” Paul Levitz noted on Facebook. “We should all take a note from this man's book that he's closed with such honor. It's possible to make wonderful art, have a life full of love and friends, and do your work well for many decades. But most of us won't manage to do it all, or do it as gracefully.”