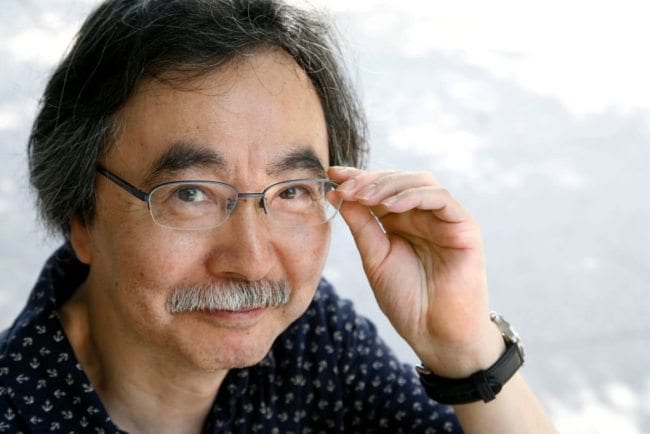

First off, I’m going to give him his proper titles—Chevalier Jiro Taniguchi, de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, Maestro del Fumetto. Because when you are paying tribute to a comic book artist who has been knighted by the French government and titled in Italy, you do him full honors. Of course, those are not Taniguchi’s only awards—he had the usual collection befitting a manga genius, including receiving the Osamu Tezuka Culture Award and the Shogakukan prize—but being named Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters and Master of Comics is something special.

First off, I’m going to give him his proper titles—Chevalier Jiro Taniguchi, de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, Maestro del Fumetto. Because when you are paying tribute to a comic book artist who has been knighted by the French government and titled in Italy, you do him full honors. Of course, those are not Taniguchi’s only awards—he had the usual collection befitting a manga genius, including receiving the Osamu Tezuka Culture Award and the Shogakukan prize—but being named Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters and Master of Comics is something special.

You’ve never heard of the esteemed Chevalier Taniguchi? Don’t feel too bad. I had never heard of him either, until several years back when I was still doing manga reviews and hunting around for a publisher willing to take a chance on Shigeru Mizuki. I crossed paths with Stephen Robson at Fanfare / Ponent Mon, who basically said "Have you heard of Jiro Taniguchi?" and sent me a care package full of books. It was one of the loveliest boxes I have ever received. The first one I read was The times of Botchan, followed by The Quest for the Missing Girl. I was instantly hooked.

And slightly surprised that I had never heard of him. Although respected and admired in his native Japan, Taniguchi was not exactly a household name. His quiet, introspective brilliance was not the sort of thing that splashed out from the cover of magazines, or got molded into plastic figures. His voice was much more appreciated in Europe. A Belgian film company produced a live action adaptation of his comic A Distant Neighborhood, changing the setting to Paris. He collaborated with legendary artist Moebius. His work inspired an art movement in France called Nouvelle Manga, led by Frederic Boilet and Benoit Peeters, with whom Taniguchi worked on the comic Tokyo is My Garden.

And slightly surprised that I had never heard of him. Although respected and admired in his native Japan, Taniguchi was not exactly a household name. His quiet, introspective brilliance was not the sort of thing that splashed out from the cover of magazines, or got molded into plastic figures. His voice was much more appreciated in Europe. A Belgian film company produced a live action adaptation of his comic A Distant Neighborhood, changing the setting to Paris. He collaborated with legendary artist Moebius. His work inspired an art movement in France called Nouvelle Manga, led by Frederic Boilet and Benoit Peeters, with whom Taniguchi worked on the comic Tokyo is My Garden.

In recent years, Taniguchi started getting wider recognition in his home country. His work Solitary Gourmet had been adapted into a television series in 2012-2015, and his comic The Summit of the Gods that he did with writer Baku Yumemakura was adapted into a live-action film in 2016. It is some comfort to know that he survived long enough to see this appreciation of this work—for at only 69 years old he died far too young.

Taniguchi was born in Tottori prefecture. That particular slice of Japan seems to produce more than its fair share of giants of manga—both Shigeru Mizuki (Kitaro) and Gosho Aoyama (Detective Conan) hail from Tottori. (A fact not lost on its tourist board, which bills themselves as Manga Paradise. Although while Mizuki and Aoyama have dedicated sites, Taniguchi is largely unrecognized). After graduating from Tottori Commercial High School, Taniguchi moved to Kyoto in 1966 to start working at a textile company. But he had no intention of remaining in that occupation.

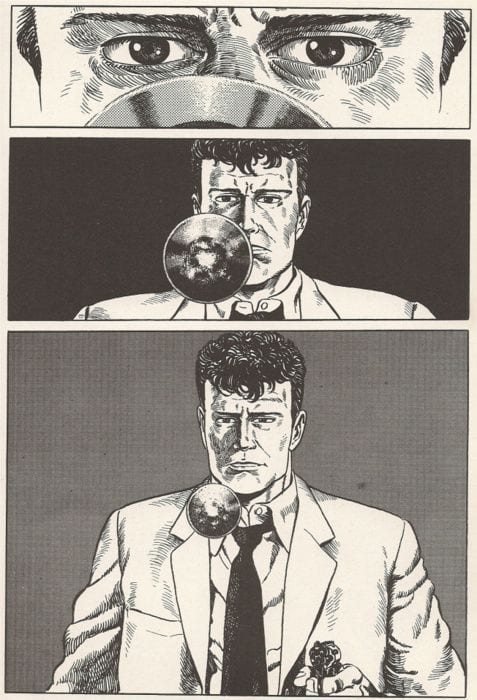

In the late 1960s, he met manga artist Kyota Ishikawa and began his training as an assistant. In 1971, he made his debut with The Damned Room in Weekly Young Comic. He continued his training as an assistant to Kazuo Kamimura (Lady Snowblood), before breaking out for a solo career. Taniguchi partnered with writer Natsuo Sekigawa to produce some brilliant hard-boiled crime fiction. While Taniguchi would later be known for his gentle slice-of-life fiction, stories like Hotel Harbor View and Trouble is My Business showed he knew how to draw a man getting a bullet in the face.

In 1987, Sekigawa and Taniguchi launched into what is one of my personal favorites, the 10-volume The Times of Botchan. What began as a simple two-volume exploration of the life of writer Natsume Soseki, blossomed into an exploration of literature in the ever-changing Meiji period. Sekigawa and Taniguchi populated their story with luminaries such as Ogai Mori (Vita Sexualis) and Lafcadio Hearn (Kwaidan).

Taniguchi’s art—his use of simple lines and his ability to capture expression—pushes the work beyond a simple academic exercise. There is a scene where Hideki Tojo appears as a young child that is absolutely chilling, an effect Taniguchi pulls off with minimal distraction and pure clarity of intent.

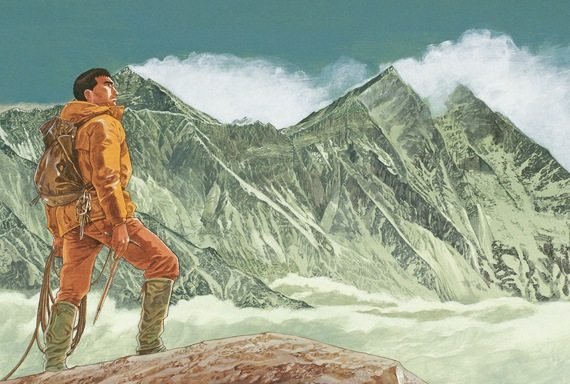

Over the following years Taniguchi worked with other writers as well on his own. He produced comics in almost every genre imaginable, including crime fiction and funny animals, adventure and fighting, science fiction and young adult. In 1986, he did the comic K with writer Shiro Yosaki, in a genre that Taniguchi would become the undisputed master of—mountain climbing. The story follows a mysterious Japanese man living at the foot of the Himalayan Mountains, making his living as a guide to climbers.

Through Taniguchi’s stunning nature scenes, he captured the splendor and terror of climbing these mighty peaks. He followed K with comics like the 5-volume The Summit of the Gods, a work that follows the real-life mystery of George Mallory, who went missing on Mt. Everest. The Summit of the Gods is intense—there is no other word I can think of to describe it. There is no better comic about Mt. Everest.

Taniguchi further combined mystery procedural with mountain climbing in the emotional The Quest for the Missing Girl, which is another one of my favorites. This look into teenage prostitution and corporate cover-ups remains a chilling examination of one of the darkest sides of modern Japan. His research and commitment to portraying realistic climbing is incredible, as well as his ability to portray sweeping mountains scenes. Taniguchi makes you feel the bitter cold and intensity of clinging to a sheer face with only your own strength and equipment to keep you alive.

In 1990, Taniguchi turned his eye away from gangsters and mountain climbers to look inside at his own life with The Walking Man. Here another Taniguchi hero emerged: the middle-class, middle-aged man becoming aware of his own surroundings. This Zen-like, introspective hero would appear again and again, in semi-autobiographical comics like A Zoo in Winter, the fantasy-tinged A Distant Neighborhood, and the foodie comic The Solitary Gourmet.

It is this aspect of Taniguchi that appealed to French readers. His simple, reflective storylines touched a deep cord in France, who resonated with the comics’ appreciation for nature and daily life that are not quagmired in nostalgia. From 2007-2008 French jeweler and luxury brand Cartier used Taniguchi’s art for a commercial campaign that spread his fame across the country—a bit ironically, considering Cartier is selling a lifestyle completely at odds with Taniguchi’s portrayal of middle-class life. France also loved Taniguchi enough to commission Guardians of the Louvre, a fanciful story about a lone Japanese man wandering through the ancient art gallery, conversing with famous paintings in a mad fever dream. And lest you should think of Taniguchi as only a wise prophet of the nobility of a peaceful life, while he creating these idyllic portraits of modernity he was also drawing Fatal Wolf, an ultra-violent wrestling comic. Taniguchi was a multi-faceted jewel. One of those facets was huge, rippling muscled men attempting to tear each other apart. The guy could draw an exquisite blood stream.

I never met Jiro Taniguchi, but from all accounts he was very much like that person you see in his introspective comics. The word “gentle” is what you most hear in association with him, and that makes perfect sense. Gentleness exudes from his work, although it is gentleness bulwarked by intense resolve and strength. I imagine he was much the same. An artist as driven as he was, and as dedicated to his craft, much of his own character must have seeped into his work. When my hero Shigeru Mizuki died, it was accompanied by the bittersweet knowledge that his death thrust him into the spotlight. Many discovered his works only because of his death. I hope the same thing for Jiro Taniguchi.

Thanks to Fanfare / Ponent Mon, there is a wealth of Taniguchi works available in English now. I often recommend people start with The Quest for the Missing Girl, which is a good blend of Taniguchi’s humanism combined with the intensity of his climbing scenes. It’s also a single volume story, so not as much of a commitment as The Summit of the Gods—although you will eventually want to tackle that particular mountain. Another book to try is The Walking Man, probably Taniguchi’s most popular work in English. One description it doesn’t seem so interesting—a man walking around, discovering his own neighborhood—but Taniguchi transforms it into something sublime. Just try not to go on your own walk through your own neighborhood after reading it. Just try. And then see how much your sense of the world has been changed.

After I heard of his death, I pulled my Taniguchi books off the shelf and have been re-reading them, one-by-one. Damn, they are so very, very good. Goodnight Chevalier Jiro Taniguchi, de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, Maestro del Fumetto, Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters and Master of Comics.