Aubrey Sitterson’s career in comics began as an intern at Marvel in the Mid-2000s. Upon graduating from NYU in 2005, he worked at Marvel as an Editorial Assistant, then as an Assistant Editor. Following his departure from Marvel in 2008, he took on content writing responsibilities at WWE.com. He began his freelance career in kind, beginning in in 2010. This included copywriting responsibilities for both Marvel and DC, as well as editing work on titles like Kick-Ass. During this period, Sitterson began landing gigs as a comics writer, beginning with shorts and and back-ups for DC and Oni, as well as work on Robert Kirkman and E.J. Su’s Tech Jacket, co-written with Kirkman, which ran as a backup feature in Invincible. In addition, he worked on adaptation work for Viz Media and Marvel. In 2012, he collaborated with artist Chris Moreno on the graphic novel Worth, for Roddenberry Entertainment and Arcana Studios. In recent years, Sitterson produced work on licensed titles for IDW, such as Street Fighter x G.I. Joe, followed by a much-lauded run on G.I. Joe with artist Giannis Milonogiannis. This series segued into another, Scarlett’s Strike Force, which was abruptly (and controversially) cancelled. Throughout this period, he also pursued passion projects, such as his fantasy fiction podcast Skald, which ran from 2015 to 2018 and was subsequently collected into prose editions. In 2018, Sitterson, with artist Chris Moreno, published The Comic Book Story of Professional Wrestling, an ambitious summation of the sport for Ten Speed Press. In 2019, with artist Fico Ossio, he published No One Left to Fight, a Western take on fight manga, for Dark Horse. Sitterson is launching a Kickstarter to produce his latest project, Beef Bros, in collaboration with artist Tyrell Cannon (ERIS, IDKFA).

Aubrey Sitterson’s career in comics began as an intern at Marvel in the Mid-2000s. Upon graduating from NYU in 2005, he worked at Marvel as an Editorial Assistant, then as an Assistant Editor. Following his departure from Marvel in 2008, he took on content writing responsibilities at WWE.com. He began his freelance career in kind, beginning in in 2010. This included copywriting responsibilities for both Marvel and DC, as well as editing work on titles like Kick-Ass. During this period, Sitterson began landing gigs as a comics writer, beginning with shorts and and back-ups for DC and Oni, as well as work on Robert Kirkman and E.J. Su’s Tech Jacket, co-written with Kirkman, which ran as a backup feature in Invincible. In addition, he worked on adaptation work for Viz Media and Marvel. In 2012, he collaborated with artist Chris Moreno on the graphic novel Worth, for Roddenberry Entertainment and Arcana Studios. In recent years, Sitterson produced work on licensed titles for IDW, such as Street Fighter x G.I. Joe, followed by a much-lauded run on G.I. Joe with artist Giannis Milonogiannis. This series segued into another, Scarlett’s Strike Force, which was abruptly (and controversially) cancelled. Throughout this period, he also pursued passion projects, such as his fantasy fiction podcast Skald, which ran from 2015 to 2018 and was subsequently collected into prose editions. In 2018, Sitterson, with artist Chris Moreno, published The Comic Book Story of Professional Wrestling, an ambitious summation of the sport for Ten Speed Press. In 2019, with artist Fico Ossio, he published No One Left to Fight, a Western take on fight manga, for Dark Horse. Sitterson is launching a Kickstarter to produce his latest project, Beef Bros, in collaboration with artist Tyrell Cannon (ERIS, IDKFA).

Sitterson’s work is informed by well-honed obsessions, consistently exploring themes of masculinity, physicality, physical struggle, and gender roles through the lens of mainstream genre storytelling. Given his worldview, these emerge as radically challenging to the status quo and, at times, the readership. Nonetheless, Sitterson is relentlessly optimistic about the potential his stories have to illuminate and subvert longstanding conventions. In conversation, he is fervent in expressing his gratitude for the opportunity to tell stories in this way. He spoke to Ian Thomas by telephone and email in October of 2020.

Ian Thomas: How are you doing? How has 2020 been for you?

Aubrey Sitterson: I’m excellent, man. I’m really good. I’m trying to get better about not qualifying it, but I still feel like I need to. With everything going on, I feel guilty saying it, but I’m doing really well.

Good, I’m glad to hear that.

I feel really fortunate and lucky and grateful and yeah, I don’t know. We’re doing this in advance, so who knows what will be going on when this goes live. [Laughs] I’ve got the Beef Bros Kickstarter, which is probably running right now as people are reading this, I’ve got really exciting stuff planned for 2021 that we’re a little bit out from announcing. Yeah, man, all the plates are spinning.

Can you talk a little bit about your background? Where you grew up, where you went to school, and all that kind of stuff?

Sure. Yeah, I was born and raised in Richmond, Virginia. We bounced around some, but that was home. That's where my folks are from that's where their folks are from and going way further back than I care to go on ancestry.com. That’s mostly where I grew up, too. I left when I was eighteen to go to school in New York. I went to NYU and I lived there for about eleven years.

What were your early or formative experiences engaging with comics?

Yeah, we would move. As I said, Richmond was home. Richmond was where I was born. To this day, I’m like the only member of my extended family that doesn’t live in the Richmond area, but we would bounce around. We lived in North Carolina for a while. We lived in New Jersey for awhile. And whenever my grandfather would come visit, or sometimes he would just mail them to me, because here’s the thing, and as a little kid this blew my mind, they get different comics in the newspaper in different places.

Right.

Different newspapers had different syndicated comic strips. So my grandfather would send me the Richmond Times-Dispatch comic strips that I couldn’t get where I was living in North Carolina or New Jersey and that was the earliest memory of comics for me.

I’m trying to think of comics from that era? Was that like the Far Side era? The Fox Trot era? Those are the ones that I think of from that time.

It was earlier. I’m going to date myself now. [Laughs] Normally, I like to keep it mysterious, but now we can do the geological excavation. My favorite comic strip as a kid was Outland.

Oh! Yeah.

Which is Berkeley Breathed. And I later went back and became a really big Bloom County fan. They had Outland collections at WaldenBooks at the mall and they were racked next to this thing that looked the same and had some of the same characters, so I went back and became obsessed with Bloom County. I still have my collections of both Outland and Bloom County.

I go back and re-read them. Every few years, I pick them up and read some of them. There was so much that went clear over my head as a kid, that I didn’t understand, because it was a very political and socially aware strip, that it did not make sense to me or I just wasn’t ready to consume it or I didn’t know the history or the context for it. Every time I go back and re-read those, I find them funnier and smarter and more biting because I know who these people are that they’re talking about. [Laughs]

Right. That’s funny, Outland and Bloom County were actually part of my first comics experiences, also. I do remember Outland as being such that, at least in syndication here in Pittsburgh, they gave that strip a lot of real estate, so it was a really spread out, nice looking comic.

It was. Especially on Sundays, too. It was really beautiful, artfully selected colors.

Yes, absolutely.

It was the prettiest of those comics. It was still drawn really cartoon-y because that’s how Berke Breathed draws. Here’s the other thing I really loved about it. Somebody’s going to look up an old Richmond Times-Dispatch and argue me on this [laughs], but, as I remember, it was the only fantastical comic strip, outside of like, Hagar the Horrible, at least in my newspaper. Everything [else] was very real world and realistic, which is fine, I like that stuff, too, but reading the thing with, like, purple hills and weird orange trees and this big-nosed penguin walking around having conversations with people, that was my speed.

So you started working for Marvel right out of college, is that correct?

Yes, sir.

And you took on a variety of roles there.

I started as an intern when I was still in college. And then I was an Editorial Assistant, which is a part time job that I had while I was still in college. At the time—I think this has changed, I think they pay their interns now, which is good. They should be [Laughs], that’s excellent. But at the time, we weren’t, so I was an unpaid intern for a while, then I was an Editorial Assistant, which was a part time job that I did while I was finishing up college, then I moved into an Assistant Editor role.

I was only ever an Assistant Editor, but that’s kind of a misleading thing to say because Assistant Editors at Marvel will often times—I remember at my peak I was lead editor on four monthly titles, as an assistant. It’s a weird thing. I was an Assistant Editor, but I was credited as an Editor on a bunch of things.

Were your assumptions about the industry, as you entered it and began to work in it, in keeping with your actual experience? Which notions were you disavowed of and which were confirmed?

It took me a long time to get it, man. [Laughs] I wasn’t a great comic book editor for a bunch of reasons, one of which was that I wanted to be writing. This is not uncommon. If you’re an editor and you want to be writing the story and you’re giving notes on it, your notes tend to skew towards how you would do it and the story that you would tell.

At the end, the job of the editor is to help the talent create the best book that they can make not the version of the book the editor wants to make. So, I was not great at that because I always wished I was writing the book. [Laughs] I wasn’t really good at that job and that’s one of the reasons why and the other reason why is I was still very much enamored of and believed in the idea of a meritocracy and I knew I was really great and smart and charming and handsome. [Laughs]The handsome thing probably wouldn’t come into play, but that was there, too. And I thought, “just straight up to the top from here,’’ right? "Right out of college, I’m working at Marvel, I’m just going to zoom up the ladder.”

This is mid-2000s, so pre-crash. It took me a long time to realize this. I was long gone from Marvel when I realized that my job wasn’t to put out good books, primarily. If that happened, everybody was pleased. Nobody was angry that a book was good, but my job, primarily, was just to smooth things over, just to make my boss’s job easier, just to keep my boss happy and not cause problems and I didn’t do either of those things. [Laughs] I did nothing but cause problems and irritate my various bosses there because I really did truly believe that my job was to make every issue of everything that I was working on the best possible thing it could be, to come out on time, for everything to be run like a well oiled machine that produces beautiful, amazing comic books and that’s not really what anyone wants from an Assistant Editor because an Assistant Editor trying to do that is a real pain in the ass, right? [Laughs]

Now it’s really different, right? With social media and the way things are discussed and access, people have a really clear idea of what goes on at these comic book companies now, or at least they think they do. They have some kind of window. At the time, I didn’t have any window. There were forums and stuff, but I wasn’t really a big forum guy, so I didn’t know a lot of it, so I didn’t really have illusions to lose other than broader illusions about the nature of work and jobs.

And then the intervening years taught you those lessons.

It took me longer than it should have to learn. [Laughs] It took me stints at WWE and THQ and 2K, which were dream jobs. It took having a bunch of dream jobs to really figure out the nature of work.

Okay, so moving on to your current project, Beef Bros. Can you talk about how you hooked up with Tyrell Cannon, the artist on your upcoming book?

Yeah, man. First of all, let me correct you. Tyrell is not the artist on my upcoming book, he’s the co-creator of our book. That’s important and I try to police myself with that a lot. It’s like a constant discussion, but I think it should be. Tyrell’s not a guy who came in as a hired hand or a work-for-hire guy on Beef Bros. This is our book.

I first started talking to Tyrell because of Grim Wilkins. Grim Wilkins is an amazing cartoonist. He did a book called Mirenda that’s brilliant. It’s beautiful, but also it’s mostly wordless and the amount of subtlety that he is able to convey through gesture and page layout alone is miraculous, I think. But, anyways, Grim rules. Grim, one day, out of nowhere on Twitter—maybe it was a reply to some goofy prompt-he said “I would love to see what Aubrey and Tyrell would cook up together.” I wasn’t familiar with Tyrell’s work at that point, but I trust Grim and who doesn’t like to make a new friend, right? So I went and followed Tyrell and started checking out his art and I realized that we have a lot of overlap in terms of our love for low culture done intelligently. Like, low brow stuff done well and smartly, especially when it comes to big, beefy dudes, doing action-packed violent things. Tyrell’s obviously really good at that. You can take a glance at his artwork and see, but the other thing that he’s really great at is conveying actual tangible emotion and, again, subtlety.

I know that’s the second time I mentioned that in a short span of time, but, to my mind, that’s the number one most important ability for a person drawing a comic book, being able to convey things through facial expressions. Because, otherwise, I find it an emotionally bereft experience. Tyrell is amazing at that. I don’t know if you read his ERIS book. It’s big, musclebound, violent sci-fi action, but it’s also done conscientiously, where choices are made for clear reasons and it’s a deliberately structured and plotted and presented piece of artwork and that’s what I really responded to in Tyrell’s work.

So, you have been teasing the announcement with such things as ads from the video game Double Dragon, pictures from JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure—

—the Barbarian Brothers. I did one today from Bio-Dome.

I guess maybe the Bio-Dome reference doesn’t fit with this. Bio-Dome kind of threw me. I was going to have you talk to me about beefcakes.

We can talk about beefcakes. We can and should talk about beefcakes.

Okay, so talk to me about beefcakes.

Sure, the comic is called Beef Bros. The comic grew out of conversations that Tyrell and I had about a bunch of different stuff and about basically all the things that we love: Pro Wrestling, big eighties-era bodybuilder dudes, action movies, brawler beat ‘em up video games, like Double Dragon and Streets of Rage, bonkers, specifically eighties Seinen manga, like Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure and Fist of the Northstar.

That’s the milieu that speaks to us. That is the cultural and genre milieu that hits us right in our core and I think that beefy dudes sit at the center of a lot of that. I’m a well-documented wrestling fan, but I think one of the coolest and one of the uniquest things about wrestling in the contemporary American mainstream Pop Culture landscape, and this is changing for the better, I think, but one of the fascinating, maybe contradictory things about wrestling to people who aren’t as deep into this stuff as I am is that pro wrestling is a place where straight men can safely and not self-consciously celebrate the beauty of the male form.

To digress a little bit, I think this might be a good time to bring up your overall use of archetypes and tropes and visual shorthand. One thing that I found to be effective in The Comic Book Story of Professional Wrestling, was your use of signifiers to encapsulate broad swaths of information. How did you go about researching and organizing the information in The Comic Book Story of Professional Wrestling?

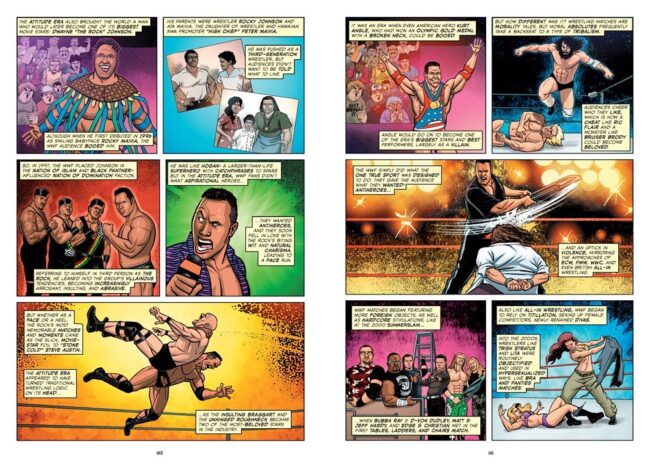

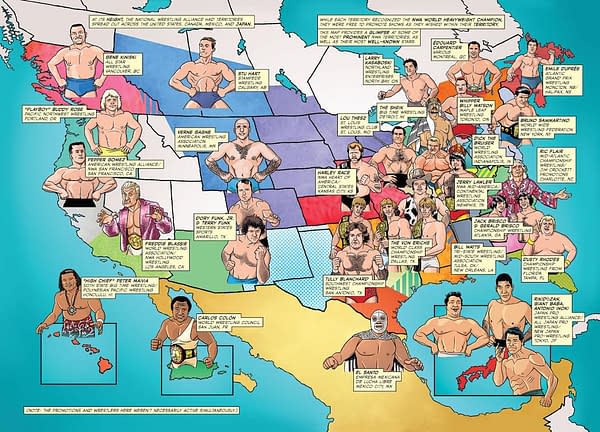

I tell people that CBSOPW was exhaustively and exhaustingly researched. Fortunately, decades of watching, writing about, reading about, and talking about wrestling had left me with a pretty good general idea of what we needed to cover and, just as importantly, where to find that information. The first step was page breakdowns for all of the book's 170 pages, a roadmap that allowed me to craft all these disparate facts into an actual story (as opposed to just a list of anecdotes), make sure we could fit everything in, and identify any gaps where I needed to do additional targeted research.

At that point, I figured I was pretty much ready to go and made my schedule for getting the thing written. I'd done enough comics by that point that I had a pretty solid idea of how fast I was. The thing I didn't take into account though, was that all my previous work had been fiction, and doing 20 pages of G.I. Joe laser battles is somewhat less time-consuming than a densely researched work of nonfiction. I finished writing the first page of CBSOPW, looked at the clock and said "OH NOOOOOOOO," because I just hadn't considered the fact that I would need to not only double-check every date and name and promotion and match outcome, but also go about digging up visual reference to make sure everyone was wearing the right ring gear for whatever period was being depicted.

In writing The Comic Book Story of Professional Wrestling, what were your goals? What audience did you have in mind? Were you aspiring to a certain level of objectivity? A certain depth and breadth of coverage?

So, I think the first thing to understand is that I typically don't like these types of books; the sweeping nonfiction comics. Too often, they read as slight, the result of shallow Wikipedia-research, and, as alluded to up above, more just a series of anecdotes than any kind of coherent narrative or story. In fact, when our editor Patrick Barb came to me asking for a pitch, the biggest part of my accepting the challenge was knowing that I'd be furious if I saw that someone else was writing the wrestling history comic. Like so much great art, CBSOPW grew out of spite.

I really wanted to make a version of a nonfiction comic that I'd actually enjoy. My co-creator Chris Moreno and I had a bunch of lengthy conversations about this because, unlike me, he's always been a big fan of this type of material. We came to the conclusion that what I find is often lacking in nonfiction comics is that connective tissue; books that feel content just to run down a checklist of facts, famous people, and events. To combat that, we established a few thesis statements for the book, ideas and thematic considerations that could inform the structure of the book, how we choose to present the information within, and, perhaps most importantly, what information we even chose to include. To my mind, the act of curation is the most important part of writing nonfiction; by establishing early on what larger, broader points we wanted to make and explore about wrestling, we were able to look at every panel and determine whether it contributed to this larger whole we were attempting to create.

As for the audience, we really wanted to make something that celebrates professional wrestling and could act as a primer for someone who knows absolutely nothing. A book you pick up if you finally want to understand why people go nuts for this stuff. So, from that perspective, it was really about developing a kind of crash course in wrestling, giving new fans everything they need to be conversant in the subject, from major figures, important historical events, even wrestling jargon and slang. We wanted to make something that someone could read and then get right into arguing on wrestling forums and subreddits. But at the same time, we knew that in order to have staying power, to become the type of perennial seller that the book has turned out to be, we knew we needed to hook those diehard fans. I think that's where our "thesis statement" approach and that exhausting research really came in, as there's something more to the book for hardcore fans than just confirmation bias, seeing stuff you already know drawn on paper.

That's why it's such a huge thing for us when actual wrestlers compliment the book, or all the folks who gave us blurbs ahead of publication. Wrestling is all about obfuscation, which makes it notoriously difficult for outsiders to chronicle and discuss; knowing that people who've dedicated their lives and sacrificed their bodies to this art form approve of the job we did means the world to us. Truthfully, that's who I was trying to impress with it.

How much of the visual aspect was conveyed to Chris Moreno in the scripting?

After all my talk about building projects organically with co-creators…CBSOPW wasn't that at all. The idea for this book existed with our editor Patrick before either of us were onboard, so while it's ours and we own it, in terms of workflow it had more in common with a job you get hired for as opposed to a project you pitch from scratch. From jump street, I knew that Chris was the guy to draw this thing though. Not only is he a wrestling fan, so he understands what's good about this stuff, but he is incredibly adept at both caricature and period material, which are both wildly important for doing a nonfiction comic.

We didn't want this to be a lightbox comic, full of stiff postures and wooden expressions, so we needed someone like Chris, a true cartoonist, to come in and distill these real life figures down to their essence, which was no easy task when you consider how many real life people show up in this thing. That's just the beginning of Chris' genius though. That guy grew up loving those old Will Eisner preventative maintenance magazines and any kind of nonfiction comic he could get his hands on, so he had a ton of fantastic ideas for how to present information visually, stuff that you typically don't see in the more narrative-based comics that have always been my wheelhouse. Some of that was material we discussed ahead of time that I could script around but I think much of the best of it was stuff that Chris figured out on the page. So while I spent an exorbitant amount of time finding photos of the exact right Macho Man outfit, it was Chris who figured out how to keep presenting factual information in ways that are so visual and dynamic. I know I learned a ton from Chris on this book and it's stuff we've really been leaning into on our new project, which you should hear about in just a few months!

I feel like much of your career has been an exploration of masculinity, physicality, and, maybe to some degree, gender roles, in one way or another. Do you find that these things are consistently on your mind?

I think about it a lot. I find it hard not to think about it because it is such bedrock, foundational stuff, not from a biological level, but from a cultural level. From a very young age, you are gendered. You have expectations and roles heaped on you, based on your gender. It varies from place to place and culture to culture, but that stuff has long tendrils. I’m not one of these guys who wants to reduce everything to childhood trauma or “That guy is so insecure in his manhood!” But that stuff does sit at the root of a lot of the convulsions that are going on presently across not only pop culture, but politics.

I find that stuff fascinating. I think that—and this is where the Bio-Dome stuff comes in—tied in with that is this weird contradiction. You are taught and encouraged to celebrate this masculine form, as an ideal, a paragon, something to aspire to, but you’re also shamed for appreciating it and you’re also taught to be extremely fearful of things like affection and warmth and generosity and that’s a big part of Beef Bros.

Beef Bros is big, beefy bros and they love each other and they are open about it and they are not ashamed about it and it informs everything that they do as big, beefy bros. Part of the goal of the project is to depict a form of masculinity that is not toxic. I don’t want to ruminate on toxic masculinity. A lot of people have done that and it’s been done really well.

That’s not what this project is about. This project is about creating something aspirational, saying look, you can be a big, beefy bro. You can be yoked to the gills and fit into this nineties Dan Cortese aesthetic, but that doesn’t preclude also being kind and gentle and giving and loving. And, honestly, maybe I’m projecting on Bio-Dome a lot, but those guys love each other! There’s something really powerful there and maybe even revolutionary, I think.

I think that might be one of the unstated draws of buddy comedies, in general.

Dudes who love each other.

Yes.

Honestly, if I may, it’s the reason Jackass is so good and every show that’s been a Jackass formula since then has not been as good. All those guys on Jackass loved each other and were having a blast and that’s a thing people like seeing. People like seeing men, grown men, loving and appreciating and being kind to each other.

It’s a remedy to this poison we’re confronted with all the time in the way that masculinity is depicted, the way it used, the way it is portrayed, and the way it is perverted. I think that’s one of the greatest things about Jackass. Also, it was just funny watching those guys get hurt [laughs], but the love, too. Both of these things.

You have spoken in the past about “fight-based storytelling,” in which fights are the driver of the storytelling, as opposed to, I assume, a break from the storytelling. I think that you really leaned into this in No One Left to Fight. Do you see Beef Bros as a further exploration of the potential of this “fight-based storytelling” and what is the appeal there? Is it the same territory as the wrestling stuff for you?

Yeah. If I had to compare it to No One Left to Fight, No One Left to Fight is really Fico (Ossio) and my—I always pedantically correct people. I don’t see it as a deconstruction of Shonen fight manga, I see it as a contribution, as a riff, as an American contribution to that genre. Of course, because we’re working in that genre, fighting has to take a serious role. There is definitely more of an influence of fight-based storytelling in No One Left to Fight than there will be in Beef Bros, however, that approach is something I bring to all of my work because I think that, to the second part of your question, I think that fighting and struggle is extremely potent. It’s primal. It has visceral, primal, atavistic power.

And, as such, that makes it relatable.

Yeah. Not only is it relatable, because everyone has been in a situation where they want to fight someone. Maybe that’s really telling about me. [laughs] I feel like that’s a universal thing. Not only that, but it’s such a pure, stripped-down storytelling engine and device to explore whatever it is that you want to explore and i think that is very much one of the appeals of professional wrestling. Wrestling is simultaneously the most nesting-doll complicated con, while also being incredibly base and simple.

The core of wrestling is: “Let’s have these two guys fight. Don’t you want to see that? Don’t you want to see these two guys beat the hell out of each other?” That’s the core of it and then everything else is layers on top of that, but that core is what makes wrestling work and I think that can be used to great effect in any medium and it should.

My personal opinion is that it’s difficult in comics for some structural reasons. Also, I think that just stylistically a lot of contemporary comics have moved away from the beauty of physical struggle in favor of other ways of using and exploring the medium, which is great. Let’s do all of it. But for me, what I like is people hitting each other.[Laughs] I like that. It gives me a visceral thrill and I think that if I’m reading a story, I want to feel something, and I want to be excited and I want it to grab me and I think violence and struggle are things that strike the lizard brain in everybody. If you can harness those to whatever the end of your story is, that is an amazing fuel.

Can you talk about what the pitch for No One Left to Fight looked like? What were your specific goals for the project?

Fico and I built a world. We didn't include all of that in the pitch, of course, but over the course of months worth of back and forth emails, we fleshed out the entirety of the Fightverse, the plot of the first saga and the characters in it, obviously, but also a ton of backstory regarding the gang's previous adventures growing up together. We touched on some of that in the four-pager that ran on EW.com and we've alluded to a ton of it over the course of the first five issues of NOLTF.

Our goal for the book was pretty simple: We wanted to find a way to take everything we love about shonen fight manga generally and Dragon Ball specifically and replicate it in North American-style comics. The pitch, then, became all about showing how we would create the necessary sense of scale – for the world, the character arcs, and, of course, the battles – not in dozens of 200-page volumes, but in arcs of 20-page pamphlets.

What kind of information did you communicate to Fico Ossio and the rest of the creative team?

Even outside of publishers with the full-on IP factory mindset, US comics are dominated by this assembly line approach: The writer does a script and it moves on down the track until you've got a finished comic. Not only does that give the writer an undue amount of prominence in the creative process, but in privileging the writer, and limiting the opportunity for contribution from the artist, it becomes an uphill battle to make a piece of art where all the pieces are working in concert.

That's not how I like to work. NOLTF wasn't a situation where I came up with an idea and pitched it to Fico. Rather, our starting point was simply wanting to collaborate on something because we're friends and love each other's work. Once we realized we both loved Dragon Ball and shonen fight manga – a genre that, despite its massive popularity here, has been relatively unexplored by comics creators from the Americas – we started to build around that.

Fleshing out NOLTF wasn't a typical process, but it's become the gold standard for me. We really let Fico's incredible character designs guide things, keeping everything else very loose with lengthy threads full of story and character ideas from the both of us. So, for instance, I'd say, "We need Goku and Vegeta type characters." Fico designed Vâle and Timór based on that alone, and then we started to flesh out who these guys actually are based on how they look and ideas Fico had during the design process. I don't even think we had names for them before we saw them. Once we had all the pieces on the table, it was a simple matter of figuring out how it all fit together and what we'd want to include in this first Saga.

This is a massive part of why NOLTF resonated with people; it feels complete and self-assured, like a truly collaborate piece of art, as opposed to an idea a writer had that was then sent down the conveyor belt.

In the short description you gave me of Beef Bros, you described them as Leftist superheroes. Is the content and subject matter of Beef Bros the reason why you’re funding the book via Kickstarter?

Yeah, one hundred percent, without a doubt. I think it would be silly to do something that is—Let’s just be honest. It’s not just Leftist, it’s explicitly An-Com. It embraces Kropotkin-esque, Chomsky-inspired Anarcho-Communist politics and it does so in a kind, loving, generous way that I think is at the root of that stuff. It would feel ridiculous and laughable and disingenuous and insincere to do a project like this at a place where we handed over half of the rights.

So, to put a finer point on it, this overtly Leftist positioning is not just part of the elevator pitch, but will be part of the marketing copy of the project when it’s described on Kickstarter.

Yeah, of course, that’s what it is, man. I’ve never done a Kickstarter before. This is my first Kickstarter and the big reason I’ve never done a Kickstarter before is because it frightened me. [Laughs] I know it’s a ton of work. Though, also, just from my time in the trenches of the internet, [I know that] if you’re doing a book at a publisher, what that means is that you’ve gotten an institution to sign on to this project that they think is going to be a success and that they think that, with what they bring to the table—which is substantial—which is distribution, they bring a name that means something, right? If you’re a comic shop retailer and you get this huge catalog, of course comic shop retailers value publishers. Some over others.

I have had an amazing time working with Dark Horse on No One Left to Fight. By doing it at Dark Horse, they’re co-signing it. It opens up doors for new people to appreciate this book. Getting a publisher to sign on for that is huge and valuable for books that need that support to find their market.

That’s why I’ve steered away from Kickstarter. The project has to have a strong enough hook to go broader than just the people who follow you on social media. It has to have a way to get out to this larger potential audience and, if you’re Keanu Reeves, that’s enough, right? It didn’t matter what that book was, it was a Keanu Reeves comic book, so it made oodles of bucks. I think, otherwise, you need a hook. You need something that people hear and they instantly understand and they can wrap their brain around what it is. I think that with “Beef Bros: Leftist Superheroes,” people will know what that means, especially when they see the art. They can fill in the blanks about what the rest of this thing looks like. That’s not true of every singly project, but it has to be true of a successful Kickstarter.

On social media, you’re vocal about your politics and your worldview. It seems like Beef Bros hews the closest to your worldview of the work you’ve produced to date. Is it fair to say that you consider yourself a Leftist? If so, what does that mean to you and what values do you associate with it?

That’s a great question and I feel like it’s a question not enough people talk about, not just in comics, but in general. I do. I do consider myself a Leftist and I’m comfortable saying that because it is so broad as to be almost meaningless. It’s a huge bucket and that’s just kind of the nature of politics in a two party system that things have to get thrown into huge buckets. AOC [Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez] said something a while back that I thought was really astute, something like “If we weren't in a two party system me and Joe Biden would be in different parties. We wouldn’t even be in the same party. We’re so far apart from each other.” [laughs] So yeah, I consider myself a Leftist and what does that mean? Ughh, man, that’s tough! I think that you’re right, Beef Bros is one hundred percent the closest to my worldview of anything I’ve done, although, giving it a run for it’s money, I have a short story in an anthology called Maybe Some Day that A Wave Blue World did. Matt Miner and Eric Palicki were the Editors on that and Nick Pyle and I did a short in that that is explicitly my worldview.

To me, what that means and the starting point—You’re getting into Aubrey deep lore here [laughs]. The way I like to look at things—and this comes from being a hyper-rational, overly-analytical, nerdy kid—I like to look at root causes. I like to burrow down into “What are our assumptions?” and proceed from there. Let’s first agree on what we’re assuming. That comes from logic courses and a philosophy background and stuff like that, too, but, for me what separates Leftists - and the degree to which they believe this and how far they want to bring it out determines where they fall on the Leftist spectrum—the thing that distinguishes someone on the Left from someone on the Right, or Center, or someone of the Liberal persuasion is a belief that—and this is a Kropotkin thing—humans natural state is not competition. It’s cooperation.

When I read The Conquest of Bread by Kropotkin, which I did embarrassingly recently, it hit me really hard because it broke it down. I tried reading Kapital. It’s not fun. It’s difficult and it doesn’t feel rewarding. Kropotkin breaks it down on a really simple level. In [Kropotkin’s] Mutual Aid, which I liked, but not as much as Conquest of Bread, he goes into detail, pointing out not just examples from human development, but from animals and all over the natural world. He says that there is a perversion of Darwin’s findings. Darwin’s big contribution was species’ evolution was based on the survival of the fittest. I think that some disingenuous actors have taken that to mean that we’re all a bunch of alpha wolves just fighting each other in the forest. [Laughs] That’s not true. Wolves don’t even do that. That’s deranged What it actually means is that the populations that are most fit to survive, survive. What causes them to be most fit to survive? It’s their cooperation. That’s what allows human beings to spread out all over the Earth. Not because we’re the most vicious, territorial creatures that lock horns every time we see each other, but because we build societies and we help each other.

Not everyone is going to agree with this. It’s a very theoretical thing to be saying, but, for me, that’s the core of Leftism. That’s the core of people on the Left. It’s this idea that, no, competition isn’t the solution to everything. Competition is the solution to very little, other than maybe entertainment, or sports, or something. It’s a lack of belief in that. It’s a lack of belief in imperialism or colonialism because, again, that’s a perversion of this idea. It’s a disbelief in markets as a solution and that’s the divergence from liberalism. Liberalism puts its faith in markets to solve problems. And, again, the degree to which you believe that varies, depending where on the [political] spectrum you are. To me those are the points of divergence for people on the Left.

This is the core assumption of Beef Bros: We can work together and we should work together. That’s what gives us power and gives us strength and creates beauty, is people joining together and working together and being kind and generous with one another. I feel like a goofy hippie saying stuff like that and that sucks, right? And that’s another great thing about Beef Bros. It shows the people espousing this are the furthest away from this idea of the frail, peacenik hippie. These are massive, yoked up dudes and this is what they believe. They’re effective and they do it not through goofy theorizing but through common sense stuff. “Look you don’t have a home. There are so many empty apartments this doesn’t make any sense. Come live with us. Would you like something to eat?” That, to me, should be the core of Leftism. That’s what Beef Bros is meant to explore and proselytize. If we’re being honest, it’s meant to espouse and embrace that belief.

You recently posted some old cartoons from the international labor union the Industrial Workers of the World on Twitter.

Holy shit, those were bonkers, right?

I’m assuming these were at least part of the influence for Beef Bros. Why do you think comics are a viable medium for, as you say, espousing any political viewpoint or persuading people politically? By extension, what do you think that looks like done well and where does subtlety and nuance fit into this?

I love that in talking about a project called Beef Bros, you’re asking me where subtlety and nuance fits in. I love it. First of all, those old Wobbly cartoons, whew, holy moly! They are powerful. It’s that primal, atavistic strength that I was talking about earlier. In that case, I think it comes from exactly what I was talking about earlier. The ones I shared were the ones that hit most strongly to me. They had massive, powerful dudes holding, clubs and cudgels [laughs] and fighting back against the monsters of capitalism and exploitive bosses and imperialism. [The cartoons] operated on a level that, again, touches something is buried in all of us. [They] operate on this pure, symbolic level.

Comics lends itself to that because comics is about moments. It’s not about movement, which is a challenge. It’s something that people forget when they’re writing comics, sometimes. It’s not about movement, it’s not about tone of voice, it’s not about dialogue, really. It’s about moments. It’s about instances that you use, you create, you cultivate, and build towards and curate for the audience. If you have something really, really good to show someone, it is the best medium for it, because they can spend as much time with it as they want.

What made this current moment the right one to pursue this project? Do you think the audience for this kind of story—a story that I would describe as a political story within the genre milieu—already exists within the comics fandom? Are you courting a new audience and trying to build something from the ground up?

I don’t know. We’re going to find out. I think the audience exists, otherwise we wouldn’t be doing it. I know the audience exists for it. Everyone I’ve sent this thing to says “This is it. This is what we need right now.” It’s bizarre. I’ve heard it from a lot of people. I think that’s true. I think that we do need something that espouses these ideals in a warm, generous, optimistic way. We need something that shows a vision of the Left that is powerful, that is kind, that is aspirational, that supports egalitarian ideals, and that is based on mutual aid. I think that is something that we desperately need as a culture. As a political group, I think that there is a dearth of actual Leftist media, especially genre entertainment, due to the fallout of the Cold War.

For generations, people were rightfully frightened of openly aligning themselves with these types of politics, so they had to be buried places. You can find it if you go and look places. Read American Flagg in 2020 and see where you think that falls on the political spectrum. It’s there, but they couldn’t be as open about it. I know there’s an audience for this. You have to make the caveat of “What is a comics audience in 2020?” I don’t know. Is it people going to comic book shops? Is it people going to bookstores? I have no idea. I think there is something for everybody, but where Beef Bros is going to sink or swim is outside of the traditional comic book industry because for a really long time, going back to at least the sixties, maybe the fifties if you want to dig really deep, superheroes used to be populist champions. They used to be working-class heroes made by a bunch of working-class, mostly Russian-Jewish guys from tenement buildings in New York City. That’s who was making these things and it was a vision of empowerment from the street level.

That changed really sharply in the sixties with the Red Scare and the rise of liberalism and it continued. If you look at the comics of the eighties, there’s a reason that they’re all either centrist law and order or outright reactionary fascist power fantasies, like Dirty Harry-esque kind of stuff. There’s a reason that they’re either that, or parodies or comments on the same. That’s where the culture spun. Since then, they’ve taken on the role of super cops. By that I mean, instead of being a defense and a bulwark against oppressive, hierarchical institutions, they’ve become a tool of those same institutions. I’m not going to sit here and lecture you about the politics of, like, Batman, but that way leads madness, right? [laughs]

Do you think genre storytelling is more effective than theory when it comes to espousing political views or making a political point?

I think they serve a different purpose. Theory specifically and nonfiction writing more generally is all about laying out cohesive arguments and thought processes. It's great for people who are already onboard with a larger proposition but want to refine or clarify their understanding of it. But, if you've ever tried to "logically" argue someone into your point of view, you know it's not really the best way to get them over to your side. Most people don't change their minds like that; they do it by figuring things out in their own way.

And that's where well-crafted, conscientious genre storytelling can come in, using genre tropes as a Trojan Horse for these big ideas, such that the reader arrives at the ideas on their own. This makes the reader more open to the ideas than if they were merely told them while also allowing the new notions to embed themselves more deeply since its understanding and wisdom the reader earned themselves.

Do you think this work will antagonize the people who were bothered by your work in the past?

No. I thought about this a lot and I talked to my wife about it because I was really worried about it. I don’t think so. Because do you know what those folks—I was going to say guys, but I don’t want to make assumptions—were upset about wasn’t me or anything I said. It was that I was working on G.I. Joe.

You were just messing with the things that they loved.

Yeah, they were upset about that. That’s the thing. And the proof is, none of those folks cared about No One Left to Fight. None of them cared about The Comic Book Story of Professional Wrestling. Those things didn’t matter to them. They just don’t want anyone touching the things they loved as kids, which, fair enough, man. I’d rather be doing my own stuff, anyways. That’s always been the goal. I liked writing G.I. Joe. I wish I could’ve written more of it, honestly. I had some neat stuff, planned.

But this was always the dream. The dream wasn’t working on G.I. Joe comics to benefit Hasbro. That wasn’t the pinnacle for me. For me, it’s being able to tell the wacky stories that are in my head without any kind of restrictions. To me, the history of mainstream comics has been people discovering what role comics play now that movies exist. It used to be that comics had the "unlimited special effects budget." Now there is CGI, so what role do comics play? This has always been the conversation with comics, trying to carve a niche for itself. I think that comics does have structural, medium-based strengths that other media do not and I think the most important one, as I mentioned earlier, is the depiction of a moment and the ability to choose moments and elide material that you don’t need. You can have a really lean package that way.

Structurally and industry-wise, a massive strength about comics that we don’t talk about enough is—I remember the first time I heard it, it was the Wachowskis of all people talking about it. When they starting doing that line of comics—Burlyman I think it was called—people were asking why they were doing comics when they could be making movies. They said it was because they could do whatever they wanted. They didn’t have to get approval from anyone. They didn’t have to get approval from producers, or studios, or get what they wanted out of actors, or people on set. There were so many less cats to herd. It is an ability to get your ideas out pure and undiluted. That’s another thing that’s really exciting to me about Kickstarter. Tyrell has been luxuriating in this freedom. He’s run a bunch of successful Kickstarters already but I'm really excited about the ability to do Beef Bros, and not just to do Beef Bros, but do it in the style that we know it should be in. I’ve written the first issue already, and it’s paced entirely differently from anything I’ve ever written because I know that we have an amount of freedom to tell the story in a way that we want to in a way that isn’t tied to the same requirements that doing a graphic novel or doing a monthly comic book would be.

I’d like to circle back to stuff you said about genre. As a storyteller, do you mainly consider yourself a genre writer? What appeals to you about storytelling within the structure of genre storytelling and why, or how, does genre storytelling have the potential to engage the audience about bigger ideas?

I like jibber-jabbering about this stuff. Yeah, of course I’m a genre writer, absolutely. The power and strength of genre is that there are conventions and idioms to play with and to respond to. There’s a conversation to be had. That exists in literary fiction, too, to a degree, but maybe it just doesn’t interest me as much. I like the buried history within genre films.

I feel like it’s kind of a hack thing to talk about how much you like Quentin Tarantino, but as a kind, when I first started seeing that stuff, it was a revelation to me. It was a lightning bolt to the brain. Not only his introduction to a world of stuff I did not know about—whether it was other movies, or music, or fashion—not only did it open all those doors, but the way that it communicated and riffed on that stuff, in a way that rewards your also learning it. You get to really discover the depth of what you’re watching because the person making it is so enamored with what’s come before and the conversation being had with this material.

I think that a lot of my storytelling is informed by professional wrestling and the pacing and the beats of professional wrestling. Professional wrestling traffics in caricature and broad signifiers. This is the nature of a gimmick, so when this person comes out, you know from how they’re dressed, from the things they’re saying, from how they’re walking, from the way they wrestle a match, you know whether you’re supposed to like them or not. You make a decision. The ability to traffic in these layered signifiers and this, like, geological meaning and power is amazing. I don’t know why you wouldn’t want to use them. It’s powerful. Riffing on established story structures, established character types, the way that stories are told, what people expect from stories, what people expect from types of characters, being able to use that to your advantage in the story you’re telling, that seems like such an incredible tool. I don’t know why someone wouldn’t want to be a conscientious genre writer.

Given the shorthand you describe, I think people buy and consume genre stories with an expectation, knowing, at least approximately, what they are going to get. As a genre writer, do you think you owe the audience anything, as far as meeting their expectations.

[Laughs] I don’t owe think I owe anybody shit! I don’t think I owe anybody anything is my gut reaction to that question. There is a tendency to talk about what creators of content owe their audience and I don’t view art and creation that transactionally.

We can talk about that from a consumer experience level if you want, right? [As a consumer] you deserve a book without any typos and the printing should be good and the colors should delineate the artwork in the story, all that stuff. But in terms of storytelling choices—expectations of craft, I get it from a consumer level—but expectations of what a creator owes the audience from a story choice and experiential point of view, I don’t think I owe anybody anything. I owe somebody reading my work the experience of reading that work that they’ve purchased. The journey I choose to bring them on, well that’s what they’re paying for. [Laughs] That’s the ride, man.

You’re asking me to give you this experience. Hopefully, it’s exciting and you ruminate on it some afterwards. That’s my goal, at least, that it sticks with you and that there’s some subtlety and nuance that causes you to want to go back in and investigate it deeper. That’s the goal. Hopefully, that happens, but it’s not a responsibility. It’s not something I owe the audience. But, again, if I’m making art, I want people to enjoy it.

I’m not one of these write a bunch of things and lock them in the drawer kind of guys. I’m definitely not one to do a bunch of work and say “Look, I wrote a thing, maybe check it out.” No! This stuff rules! I’m really proud of it. I worked really hard on it. I think you should read it. I think everyone should read this thing I made. I don’t view it as something I owe people, but I’m a gladiator. I want to give the people what they want and I want to give the people what they want, whether they know it’s what they want, or not. I think that’s kind of a distinction. Audiences, by definition, and I include myself in this, we don’t know what we want from a story experience that someone is presenting to us. We might think we do and we can talk about genre tropes and specific things we like about stories after the fact, but, upfront, we have no idea. That’s what makes the work exciting.

Again, that’s why I revel in genre tropes and idioms and shorthands so much. You can use that stuff to create expectations that you then play with and either subvert, or deny, or deliver. Again, it’s a wrestling match. Toward the beginning of the match, the babyface teases his finishing move. Everybody wants to see it, but they don’t get to see it yet. Maybe they will at the end. Maybe they’ll get what they want and they’ll see the hero prevail over the villain, but maybe they won’t. Maybe something will happen to screw that up. Maybe there’s complications along the way. But it’s all based on previous knowledge of what to expect from these things. The question of what a creator owes an audience, I think is fundamentally wrong-headed because, if anything, the creator owes an audience stimulation and titillation and excitement and that has to come from a place of the unknown.

Being a genre writer, you are part of various genre-material-producing industries. I want to read a tweet that you wrote today, I believe in response to comments around Alan Moore’s recent interview in Deadline, In which he offered his opinions on superhero movies and the comics industry, among other things. You wrote: “Every time ‘Alan Moore is bitter’ discourse comes up, it makes me angrier bc it ignores his gross mistreatment while also reinforcing the asinine, consumerist idea that fictional characters and the companies that own them are more important than the people who created them.”

As a writer who has played in the sandbox of licensed characters, who also worked as an editor for the big two, can you speak to how you feel talent is valued in those cultures, or industries, or settings.

Yeah, you know, it depends on the talent, quite frankly. [Laughs] It depends on who you are. This is why it’s a difficult conversation for some people to have, right? It’s not like what I heard Will Eisner’s old studio was, where it like a sweatshop where everybody was exploited equally.[Laughs] I think, generally, writers have it best, then pencillers, then I think maybe colorists surpass inkers at this point in terms of how they’re treated, although neither are treated very well, and letterers are treated terribly.

Everybody is treated terribly because it’s a dream job.[Laughs] To some degree or another, everybody is treated terribly until their name is big enough to warrant better treatment. I don’t think that’s unusual. I think that’s how every industry works, to my jaded eye, at least.

Given the competitive nature of the industry, do you think there are ways for creatives to build power?

I don’t know. It’s tough, man. It’s really tough. There are a lot of structural barriers to it. It’s very popular to say—and this isn’t just in comics, but everywhere—to say, listen, there should be a union. I’ve tweeted that before and got people yelling at me about it from both sides. [Laughs] And yeah, man, I think there should be. I think there should be unions for everything, not just comics, but, literally, everything. That’s always the answer. Collective bargaining and organizing and standing together is the only way that any kind of worker, whether it’s in comics or something else, can build power. There are a lot of structural reasons why that’s terribly difficult in comics, so I don’t know what the path forward is.

Can you talk about what some of those structural reasons might be?

Sure, I think that for a lot of people comics is an opportunity to work on characters they love, first and foremost. I draw that distinction between myself. That’s not me, but for a lot of people it is. That’s the peak: you’re never going to get any better than working on characters that you read as a kid. I’m not saying that to run that down because, I don’t know, I watch professional wrestling, right? [Laughs] There are plenty of people who think that is just profoundly braindead and asinine. I’m not yucking anybody’s yum, but that is an impediment. To those folks, it’s enough just to be working on these characters.

That’s part of it. There are legal reasons for why it’s difficult because of how people are classified as independent contractors and the general precariousness of work in the United States right now. [There’s also] the size of the industry. The fact that a lot of what keeps what we see as the comic book industry running—and this is changing as audiences change and markets develop—a lot of what we see as keeping the industry running are people who like reading these characters. As long as what people come to comics for is characters they recognize that happen to be owned by huge media corporations, it’s a tough fight.

It’s a tough situation to try to build worker power in because you don’t have the leverage. It becomes the same problem that every industry faces with worker organization, which is that once you’ve got enough power to actually push back a little bit, you don’t really have much need to. If you’ve gotten to the point where you’re a big name at one of these companies and you’re valued and your presence and your name mean something, well, the people running these companies aren’t dumb. They pay you better. They treat you real nice. They let you do what you want to do. You’ve earned it. And so, then there is no longer the same impetus to actually push back. Again, that’s not unique to comics. This isn’t a “Here’s what’s wrong with comics” thing. This is a nature of labor issue.

Part of the reason that I wanted to interview you is that you hold these positions and are willing to expound upon them and I don’t think they are normally expounded upon.

Why is that, do you think? Are people scared?

I think so. You speak of comics as a dream job and I do think that is a big part of what keeps people in the industry.

Yeah, of course. It’s really simple. [It’s] supply and demand curves. There’s a big old supply of people wanting to make comics, so guess what? Demand’s real low. Do you know what that means for the price? It gets driven way down. It’s that simple. People try to make this stuff a lot more complicated than it is. This is something I realized when I was at Marvel and it’s one of the reasons I left. I left, primarily, because I wanted to write, but also I realized that “Shit, man, there’s nowhere for me to go here.” I watched people at my level and higher leave and what they did—again, this isn’t a knock on Marvel, this isn’t a knock on comics, this is a knock on work. [Laughs] This is a knock on the nature of un-unionized workplaces.

What I saw happen was an Editor would leave and they would hire a new Assistant Editor and they would take all that Editor’s work and divide it amongst three Assistant Editors, saving however much of that Editor’s salary. As long as that’s the case, as long as I can step aside and there’s a dozen, at least, to take my place, it’s a tough fight.

Do you feel like you are still finding your place within the industry and the best vehicles to tell your stories?

Yeah, a hundred percent. I have idiosyncratic tastes and preferences and I think that’s borne out in my projects. I think that the work I do has struggled to fit into the narrow boxes that comics, as an industry, provides. The work I do is genre, but it’s not paced or presented the way that is currently in vogue with mainstream comics. It’s also not Art Comics. It doesn’t have the same rhythms and focus points as indie comics. The artists I like to work with, similarly. I think that comes from a place of being a fan of newspaper comics and those storytelling rhythms and the use of expressionistic artwork, as opposed to realistic artwork. My preferences for that have placed me in what is, I think—counter-intuitively and contradictorily-seeming— both a more mainstream milieu, while also a more difficult realm to find success in. I’ve often felt neither fish nor fowl. And this goes back to my time at Marvel, even. I got painted as the Indie guy, but I never really saw myself that way.

It’s why I’m so excited to be interviewed by The Comics Journal, honestly. I always read and enjoyed The Comics Journal, but I also have felt that my work didn’t really fit in with the type of work that was valued by that corner of comics. It’s mainstream genre work. It’s a strange thing about comics that the type of mainstream genre work that is massively popular on television and film and in novels struggles to find a home in comics, unless it is filtered through superheroes, which is why I’m so excited about the Beef Bros Kickstarter going on right now! [Laughs] I get to use this most comics of genres to finally explore the stuff that really matters to me in a way that is paced not in accordance with market-dictates of what our audience expects pacing and structurally, but what Tyrell and I think is going to best serve the story.

Do you think that in today’s media landscape, which is increasingly competitive and increasingly dominated by social media content, artists or creatives of any stripe, can afford to just let their work speak for itself?

I struggle with this a lot. It’s tough, too, for me, because I like talking about my work. I’m proud of it. I want people to appreciate it and get the influences and that’s part of what I’ve been doing on twitter, where I’ve been showing all these images of stuff that we’re pulling from for Beef Bros, as a way to lay the groundwork. These are not prerequisites, but it’s stuff that has influenced us and that we appreciate and value and want to lift elements from.

You know how much I love genre and the conversation with the canon. I’m trying to do less and it’s tough because you want to promote the work, but at the end of the day, also, I want my work to stand on its own. We’ve mentioned subtlety and nuance a couple times now. For me, what constitutes meaningful work in any medium—comics, film, novels, music, whatever—what makes it meaningful is the work that the spectator does. And that’s why nuance and subtlety is so important. The moments you remember from artwork that you’ve consumed and enjoyed is because of what you’ve brought to it. It’s because of what you have laid upon this framework given to you and the work that you’ve done mentally to fill in blanks and imbue this work with a deeper meaning beyond what is just presented to you at the surface level and that’s true of all artwork, I think.

One of the reasons, structurally, that comics is so powerful—I alluded to this earlier—is the ability to elide and choose your specific moments. A big part of my process, too, as a writer, is trying to find the least amount of information I can give the reader that they still go where I want them to go. That, to me, is brilliant comic book writing. As few panels as possible.

Economy.

Economy, yeah, of course. I would go further than economy: Expedience. I think there’s power in it. This is not a unique thing. Scott McCloud talked about this. This was like another lightning bolt to my brain when I read it. The magic part of comics is the gutter. That’s the powerful part. You provide these images so that the reader fills in the blanks. Let them do the heavy lifting. The act of writing comics is finding a way to convince the reader to want to do the heavy lifting of the storytelling for you. Because of that, I don’t want belabor what my stories are about or what they mean or what the intention is because, truthfully—and this gets to your earlier questions about obligations to the audience—whatever somebody brings to a book, man, that’s on them. However they want to read it is fine. I don’t have to agree with it, but I’m also not going to argue with them about it because who cares, right? Let them get what they want out of it.

That changes, of course, in cases where people have taken offense. Then it becomes a tougher area to determine, but that’s why you try not cause people offense. Try to be nice, even in your writing. I don’t want to have to explain what Beef Bros is about, beyond what we’ve talked about here. I think that when people read it, it should be clear. Hopefully, it is. Hopefully, people are able to take something away from it, but I think to explain it is to ruin the magic trick a little bit.