To twenty-first century eyes, Harold Gray was an unlikely racial progressive. He was famously reactionary, for most of his life on the far right of the Republican party. In private correspondence, he said he thought Franklin Delano Roosevelt was a communist. Gray gave ample expression to his anti-liberal politics in his comic strip Little Orphan Annie, which was an allegory about how the poor (in the form of the heroine) are best aided by their own gumption as well as the occasional helping hand by the rich (in the form of Annie’s adopted father “Daddy” Warbucks as well as other benign representatives of the .01%). While Annie and Warbucks are always trying to overcome adversity through self-help, they have to fend off a wide array of leftist villains (corrupt and communist union leaders, snooty professors, meddling social workers, and demagogic politicians preaching income redistribution). Annie, a prepubescent girl, is always trying to work for a living but is often hampered by odious child labor laws enforced by officious bureaucrats.

If Harold Gray was well to the right on economic issues, he was surprisingly progressive on racial matters. During her pilgrim's journey through the American heartland, Annie befriends people of all different backgrounds. The strip was often a celebration of melting pot America with Annie happily interacting with Italian-Americans, Jewish Americans, Chinese-Americans. As against the nativism that was often pervasive in early comic strips, where foreigners were almost by definition the butt of jokes, Annie’s immigrant and non-white friends were almost invariably portrayed in a respectful light. Gray's anti-racism seems anomalous because in the early 20th century the vast majority of political activity opposing ethnic bigotry in America came from the radical left, sponsored not just by the Communist Party but also socialist and anarchist groups as well as unaffiliated progressives.

Gray’s unexpected ethnic and racial progressivism was likely a by-product of his staunchly Republican worldview which he imbued from his family. Harold Gray’s middle name as Lincoln, which he inherited from his father Ira Lincoln Gray, born just two years after the civil war. In a 1928 strip Annie refers to Lincoln as “a reg’lar honest-to-goodness he-man…. What color folks were, or where they came from, didn’t cut any ice with him. Folks were all folks to him an’ had feelin's. So he stuck up for th’ colored people. He wanted them to get th’ chance they’d never had ‘fore then.” During the first four decades of Gray’s life, the Lincolnian heritage still had an afterlife in American culture. Until the 1932, most African Americans still voted Republican in the presidential elections. And even during the New Deal era, Franklin Roosevelt, Gray’s nemesis, kept his party firmly allied with Southern white supremacists.

The issue of racism became especially fraught after the United States entered the Second World War in late 1941. The Second World War was the seedbed for the modern Civil Rights era. Arguing that America couldn't afford to be racist in a war against Nazism, civil rights groups battled to desegregate the military, a victory they wouldn't achieve until Harry Truman issued an executive order in 1948. Even within a segregated army, black soldiers asserted their rights. In the Jim Crow South, there were many incidents of African-American soldiers refusing to sit in the back of the bus, small acts of rebellion that anticipated Rosa Parks’s historic act of civil disobedience in 1955. As the American economy started humming at full wartime capacity, rural blacks migrated to the north, where they found new opportunities as factory workers. This internal immigration created a racist backlash, including a violent anti-black riot in Detroit in 1943 which left thirty-four dead.

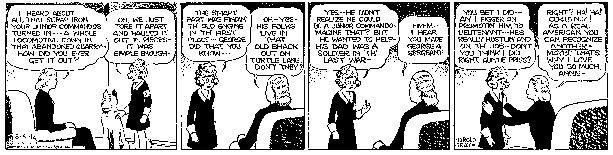

Against this background of racial strife, Gray crafted a small but significant rebuke to racism. In 1942, Gray had Annie created an ad hoc militia group called the Junior Commandos, which allowed kids to help the war effort by doing needed jobs like collecting metal for recycling and providing babysitting services to mothers working in factories. In the August 2, 1942 Sunday page, Gray showed a little black boy named George ask if he can join the Commandos. “Who says you can't be a commando?” Annie asks. “You've got as much right in this outfit as I have. You're an American! We're all loyal Americans.” This defence of George's right to be in American is framed within the context of the Junior Commandos being an explicitly multi-ethnic group, with members such as Angelo, Fritz, Marie, and Chu. (Gray repeatedly emphasized that German-Americans could be good citizens and shouldn’t be confused with the Nazis. Unfortunately, displaying a racial blindspot common to the era, he didn’t make the same distinction with Japanese-Americans. And in fact in Annie Gray vented standard racial epithets likening "the Japs" to "baboons.") George immediately proved his worth as a Junior Commando by leading the troops to an abandoned locomotive, a rich source of scrap metal. Annie rewarded George's ingenuity on the spot by making him a sergeant in the Junior Commandos.

Given the fact that many comic strips in 1942 still depicted African-Americans using minstrel show stereotypes, George was a revolutionary character. To be sure, he's depicted as being politely deferential and speaks with a slight rustic accent, but he is also drawn in the same style as the white children and displays great savvy and dignity. In terms of being a respectful portrayal of African Americans, George compares favorably to characters such as Ebony White in The Spirit, who were the norm in comics. At a time when the military was still segregated, having George as a sergeant commanding white soldiers (albeit fellow children) was a radical statement and an implicit critique of the racism in the actual military. As an anti-racist statement, the strip featuring George was at least twenty years ahead of anything else in newspaper comics.

Although he only appeared in one Sunday strip, George provoked a strong reaction from both black and white readers. Many, but not all, African-American readers were overjoyed. Benzell Graham, an 18-year-old black sophomore studying at the University of Southern California, sent Gray a “note of appreciation for the fine spirit expressed” in the George strip. She added that “my family and many friends who saw the strip join me in thanking you.” She echoed the idea of national unity that Gray had expressed in the strip, noting that, “We negroes, as all other faithful Americans, are doing our best to help win this war. It encourages us to know that our effort is appreciated.” (Graham would go on to become a school teacher and write the 1959 children's book That Big Broozer).

Graham's sentiments were echoed by Private Robert B. Mitchell, then serving in Fort Francis E. Warren in Wyoming. “I must say I am an American negro, born in the deep south and such comics are not prevalent there and hardly nowhere else save here in the west,” Mitchell wrote, adding that the ideas expressed in the strip “shall become a highlight in my life and many other negroes... Here is hoping that repetition of such thoughts and actions will be characteristic of the new era in which the world is entering. Then there will be no more wars, and what will be more heaven like?”

Helen Selgrainer of Hinsdale, Illinois was another reader who was grateful for George as symbol of national unity, saying that Annie welcomed him in the way “many of us wish to be [welcomed]. She made the lad appreciated being an American....we do want to help win the war.”

Not all African-American readers celebrated George. Elsie Winslow of New York engaged in a passionate correspondence with Gray. She acknowledged that Gray's “intentions were good” but complained that George was too servile. “The Old Uncle Tom is dead and in his place is the youth who is willing to shed his blood for America, but not in your kitchen or Pullman's as ‘George’ or ‘Liza’,” Winslow wrote. “There are so many who even deny us the will to die for America.” Winslow protested the fact that George spoke in a mild dialect, saying that a modern black youth should be shown talking like Annie.

Gray wrote back to Winslow but unfortunately his letter hasn't survived. But based on a subsequent letter from Winslow, we can infer that he wrote to defend the use of dialect as realistic, said that “we must win our point by indirection” and noted that many Southern white readers were upset by George.

“Thank you sincerely for your nice letter,” Winslow responded. “Your letter was also startling and depressing, for I had never before realized that such hatred existed. It is pretty deep, isn't it? It is easy to understand now, how you must have felt when you received my letter. Under existing circumstances, you have done a very splendid thing; your comic did create a furor. It hasn't died down....You deserve encouragement for the ‘wedge’ you've made....Being a simple idealistic fool, I like people to like me, to live in harmony with a neighbor, black or white. This I shall try to continue, no matter what. And it's very consoling to know that there are thousands more like me. Perhaps you know this and know it, will continue to drive wedges. Thanks.”

Wilamelia Wilson of New York city also objected to Gray's use of dialect, arguing that “in the deep South Negro children do not speak as you portrayed the little Negro boy in your script.” For Wilson, George was portrayed as “ignorant.” Some black readers were upset that George only appeared once, which to their minds meant that he was used only as a token and not an integral part of the strip. Henry Crawford of Cleveland wrote a note to complain that both George and the Chinese-American boy called Chu had only cameo appearances in the strip. Writing in late October of 1942, Crawford stated that “I have watched your comic strip each and every day since [George was introduced] but have failed to see the Negro or the Chinese youths appear with the Junior Commandos since. Therefore I have come to the conclusion that your introduction of them was typically American; that is to make a lot of fanfare about equal rights, democracy, etc., with no intention of ever practicing it.”

Three Civil Rights organizations – the Southern Education Foundation of Washington, D.C., Youthbuilders in New York, and the Chicago Urban League -- took an interest in George and encouraged Gray to continue doing strips of this sort. Sabra Holbrook of Youthbuilder praised Gray for using his strip as “propaganda for inter-racial unity and understanding” and hoped that Gray would continue to use the strip to promote “all the ideals incorporated in the American Bill of Rights.”

In October of 1942, A.L. Foster of the Chicago Urban League expressed pleasure that Gray created a black character who was not “a servant or a clown.” But Foster wanted to know why George only appeared once. Foster, a 49-year-old social worker and activist, was a pillar of the Chicago African-American community. An entrepreneur as well as an activist, Foster had started a savings and loan company, a music shop, and an insurance company. He had a weekly column in the Chicago Defender and ran the Chicago Negro Chamber of Commerce.

Once again, it is regrettable that we don't have Gray's side of the correspondence. He seems to have written to Foster noting that opinion on George was divided fifty/fifty, pro and con. Gray also seems to have indicated that some black readers objected to his use of dialect. In response, Foster wrote that he himself hadn't even noticed the use of dialect and urged Gray to ignore the critics, since complainers were always more vocal, and try to bring back George.

As against the complex response of black readers and civil rights organizations, the reaction of white racists was more clearcut. R.B. Chandler, the publisher of the Mobile Press Register of Mobile, Alabama, gave voice to the objections of the Jim Crow South. “Your Orphan Annie Sunday page of August 2 brought in a Negro boy character, George,” Chandler noted. “While I have heard only two or three subscribers who stated that they had read Orphan Annie for the last time because of mixing a negro character in with the white children, I want to submit my suggestion that you give careful thought and due consideration to the problem of the South on this issue.” Chandler went on to offer a justification of Jim Crow as a policy “practiced for many generations in the South.” Chandler also defended the idea of military segregation that Gray had implicitly criticized in the strip.

Surprisingly, within the context of the Jim Crow South, Chandler was a moderate representative of white opinion, however extreme he may sound today. He supported the economic policies of the New Deal even as he saw the president's wife Eleanor Roosevelt as a subversive advocate of racial equality. In 1943, when there was a race riot in Mobile, Chandler rebuked whites who had attacked black defence workers. But this stance, like his letter to Gray, came in the context of larger commitment to racial segregation and the status quo that kept African-Americans as second-class citizens.

Just as he had responded to black readers, Gray also answered Chandler's letter. Gray faced a delicate task since Chandler, as a newspaper publisher, was a client, with the ability to bite into Gray's income. Perhaps for that reason, when responded to Chandler's letter Gray declaimed any political intent and argued that he was simply trying to please a valuable demographic, urban black readers.

Gray's lengthy letter is worth quoting in some detail because it gives some insight into how he tried to balance the competing claims of a white southern editor and black readers:

Use of this particular character [George] was more tactical than tactful, no doubt. I figured it would do no harm in the South, and yours is the only criticism I have received on the matter so far. On the other had I have received considerable favorable response.

God knows I'm no reformer. I am fully as strongly in favor of the south, or any other section of the country handling its own problems as even you can be, Mr. Chandler. I am no relation to Mrs. Roosevelt [the president's wife and outspoken advocate of civil rights], either, nor do I subscribe in any way to the text that the color line should be broken down.

But as you will realize, Annie depend for her circulation on her ability to build and hold friendships with all classes. Annie fraternizes with Jews, Chinese, East Indians, tramps, gangsters of the golden hearted and rough exterior type, even with the Clergy. As she is now engaged in work involving a semi-military setup, and since colored people are in our army in large numbers now, it seemed logical that a colored boy could appear briefly and do a good job and be rewarded with at least non-commissioned rank.

New York is the largest colored city in the world, as they say. Chicago too has a very large colored population. Also cities like Cleveland, St. Louis, Cincinnati, Detroit, all have large dark towns. And since Annie too is in business after all, and since the bulk of Annie's income derives from such cities as the above, one naturally is prone to appeal to the side of heaviest financial support, and not fear too much the displeasure of those on the other side. Of course that may be the wrong attitude for me to take, but it is arithmetic, and I believe you will agree with me that it is a normal human attitude.

I appreciate your feelings on this matter keenly, Sir. I hope you see my point and realize that Annie for August 2 was merely a casual gesture toward a very large block of readers. I also hope that you, while regarding me as a Yankee, will not put me down as a Dam Yankee.

Gray's letter is a most curious performance. On the one hand, he's trying to smooth over a client in a chummy manner. But he's also reminding Chandler that Gray has other clients as well. The point about big cities with large black populations takes on some bite when we realize that the Mobile Press Register was a relatively small newspaper which only paid $11.50 per week for running Annie (of which Gray got $5.75). While trying to ingratiate himself with Chandler, Gray also wanted to remind the publisher that there were much bigger papers out there. It seems that in writing to both Chandler and to his black readers, Gray was to some degree playing both sides of the fence, telling each side what they wanted to hear. Chandler and Gray would clash once again in 1947 when the publisher strenuously objected to the anti-labor union editorializing in the strip. Once again, Gray reminded Chandler that his paper was a minor client.

If we just go by the letter to Chandler, Gray seems like a cynical figure, someone who made a “gesture” of racial goodwill to please some readers but was willing to back off when challenged by racists. This seems to support the harsh judgement of readers like Crawford, who thought that Gray (and white America as a whole) was interested in making “a lot of fanfare about equal rights, democracy, etc., with no intention of ever practicing it.” But the fact that Gray was corresponding with black readers complicates the picture: he was perhaps trying to walk tight rope, seeing what he could get away with in terms of racial progress but not go too far. And certainly those black readers who saw George as an Uncle Tom figure were right to detect a fatal ambivalence in Gray’s characterization: he was willing to portray a positive black character but he had to be deferential.

The astuteness of black reader response to Gray’s work offers a lesson in the importance of listening to the audience. Those black readers didn’t have a unified response: some hailed George while others criticized him. But what holds all those letters together is that they were judging George based on their own experiences of racism, which gave them a remarkable level of insight. They were able to gauge both Gray’s intentions but also his limitations.

The fact that George was such a deferential character and appeared only once shows the limits of the sort of Republican anti-racism that Gray believed in. His larger commitment was to an ideology of self-help and upward mobility. He tried to include African-Americans within that framework and say that they too should be allowed to participate in the American dream. But the ideology of individualism didn’t allow for participating in a social movement to overturn the racial status quo, since such a movement required group effort and not just individual excellence. Not surprisingly, Republican anti-racism didn’t have much of a future and the cause of Civil Rights would find little succor from Gray’s brand of paternalism and instead succeeded thanks to agitation from African-Americans fighting for themselves, often working with the very groups (unions and liberals) that the cartoonist despised.

This essay is adapted from the introduction to the Complete Little Orphan Annie Volume 10 (IDW).