Animator and auteur Gene Deitch (1924-2020) has passed away. Unapologetically boosting modernist and abstractionist trends within his art forms of choice, Deitch succeeded in bringing a uniquely eccentric, often affectionate body of work to theatres and TV during a terribly cutthroat period for the cartoon industry. A world without Deitch is a slightly more ordinary place.

Born in Chicago and schooled in Los Angeles, Eugene Merril Deitch—the son of Czech immigrants—became interested in graphic design early in life. But Deitch initially turned his hobby to a technical end, seeking employment as a blueprint draftsman directly out of high school.

Deitch’s blueprint work, done for the firm North American Aviation, was cut short so he could serve in the U.S. Air Force during World War II. But his wartime action was cut short as well, when pneumonia earned him an honorable discharge in May 1944. Recovering and returning to California, Deitch became a commercial artist with an emotive, abstract style, taking on cover artist and art director roles on The Record Changer music magazine. “The Cat,” a Deitch gag-cartoon character featured in the Changer, was not an animal but a geeky human vinyl collector, reflecting Deitch’s longtime love of obsessive and neurotic personalities: “It was a fanatic’s world,” Deitch later stated, “and I was one of the fanatics.” The Cat also seemed designed for film animation, his nerdy form constantly bathed in shivering motion lines.

By the time of “The Cat’s” 1948 debut, Deitch was already working in animation. Deitch’s Record Changer work had been noticed by John Hubley, a fellow jazz fan—and a key force within the avant-garde animation studio UPA (United Productions of America). Recruiting Deitch as an apprentice designer in 1946, Hubley and Steve Bosustow were excited to “mold [Deitch] into the first pure UPA director”: unsullied by the traditionalist background that other UPA staffers had experienced at Disney and elsewhere. Trained by Hubley and Bill Hurtz, Deitch worked only part-time on a per-film basis, but still moved rapidly up the studio ladder. Then, landing a full time job at the industrial animation studio Jam Handy, Deitch learned to animate and direct.

In 1951 lightning seemed to strike: Deitch was hired back at UPA, now full time at their New York office. While Deitch started as a production designer, he was named Creative Director within the year, and was soon running their commercial division, where he developed a famous series of Piels Beer ads featuring Bob-and-Ray-voiced pitchmen characters Bert and Harry Piel. Deitch also received the opportunity to direct his first theatrical short. Howdy Doody and His Magic Hat (1953) was a special UPA cartoon sponsored by Kagran Corporation, makers of the famous TV puppet show. But the modernistic Deitch considered the Howdy character—visually, a sort of Wild West Alfred E. Neuman—somewhat beneath him. When Deitch had artist Cliff Roberts revise Howdy into a typically abstract UPA lead player, a blowup with Kagran followed. While Deitch remembered the Magic Hat film as having been shelved amid the fallout, it actually did see a very limited release.

Deitch left UPA soon after, but less due to the Howdy controversy than to outrage over the Red Scare blacklisting of Hubley. Deitch’s stock remained high and a new project came fast: teaming up with writer Ruby Davidson on the comic strip Terr’ble Thompson, Hero of Hist’ry! Drawn by Deitch at his abstractionist best, it featured an obsessive kid living a secret life as a time traveler. But while Thompson picked up a head of steam in 1955, Deitch shelved it in less than a year when a new animation opportunity came.

The position seemed made-to-order: a creative director job at New Rochelle’s Terrytoons studio, with the opportunity to reshape its production slate to his will. As with Howdy Doody, Deitch wasn’t a fan of the product going in: he considered Terrytoons’ traditional stars Mighty Mouse, Heckle and Jeckle, and Gandy Goose to be “schlock cartoons.” Deitch swiftly replaced them with a more abstract and modernistic cast: Sick Sick Sidney the elephant, grouchy apartment superintendent Clint Clobber, and crazed French painter Gaston Le Crayon—not all designed by Deitch, but all typical Deitch neurotics. Deitch also supervised some famous one-shot cartoons: Flebus (1957), directed by Ernest Pintoff, pitted a naïve optimist against a resolute hater, while The Fabulous Firework Family (1959) was adapted by children’s author Jim Flora from his own recent work. Another book adaptation, The Juggler of Our Lady (1957), was a medieval “send-up [of] the perceived silliness of many religious rituals.” Based on writer R. O. Blechman’s update of a traditional legend, the well-received Juggler was even screened for an Oscar nomination, but wound up vying with another animated version of the same traditional legend—ending with neither film getting the nod.

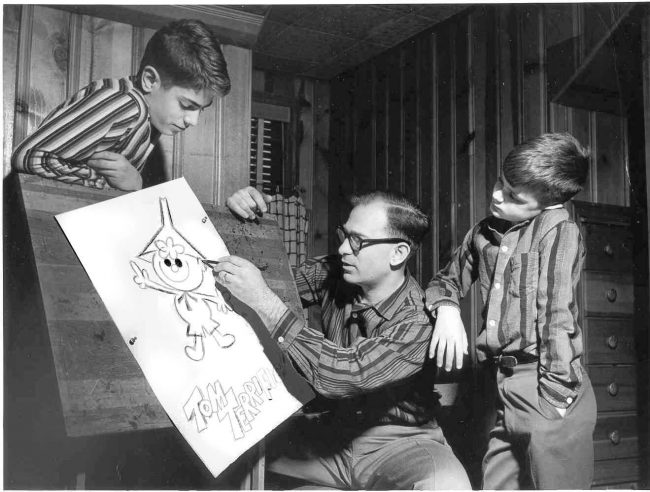

Deitch’s efforts to foster a new artistic freedom at Terry extended to letting “one-of-a-kind” animator Jim Tyer—a master of wild exaggeration—effectively run wild. But Deitch’s artsy innovations led to feuding with Terrytoons’ “reactionary” studio manager, Bill Weiss, and interference from Paul Terry, the retired CEO who still had considerable clout. Deitch was fired in 1958, but not before giving Terrytoons one of his most beloved creations: Tom Terrific, a reimagined Terr’ble Thompson with shapeshifting ability and a lugubrious “Wonder Dog” pal, Mighty Manfred. Created for the CBS children’s variety show Captain Kangaroo, Tom and Manfred became stars, with newcomer Jules Feiffer aboard to handle many of the scripts. Feiffer, developing into a brilliantly satiric writer and cartoonist, joined a crew of emerging talents Deitch brought to the studio.

Deitch’s efforts to foster a new artistic freedom at Terry extended to letting “one-of-a-kind” animator Jim Tyer—a master of wild exaggeration—effectively run wild. But Deitch’s artsy innovations led to feuding with Terrytoons’ “reactionary” studio manager, Bill Weiss, and interference from Paul Terry, the retired CEO who still had considerable clout. Deitch was fired in 1958, but not before giving Terrytoons one of his most beloved creations: Tom Terrific, a reimagined Terr’ble Thompson with shapeshifting ability and a lugubrious “Wonder Dog” pal, Mighty Manfred. Created for the CBS children’s variety show Captain Kangaroo, Tom and Manfred became stars, with newcomer Jules Feiffer aboard to handle many of the scripts. Feiffer, developing into a brilliantly satiric writer and cartoonist, joined a crew of emerging talents Deitch brought to the studio.

Deitch’s innovative reputation preceded him by now. When Terrytoons dropped him, he simply went into business for himself, opening Gene Deitch Associates and producing commercial animation. But Deitch also wanted to produce several pet projects as new entertainment cartoons—and couldn’t find a buyer.

Enter entrepreneur William L. Snyder and his animation production company, Rembrandt Films. Deitch remembered Snyder as “a man who could talk anybody into anything.” He offered to fund Deitch’s pet projects if Deitch directed them at Rembrandt’s studio in Prague, Czechoslovakia, while managing the studio for Snyder in the process. Could Deitch adjust to life behind the Iron Curtain? As it turned out, yes; though Deitch’s contract established that he should “not be required to remain in Prague for a period of more than ten days,” Deitch promptly fell in love with production manager Zdenka Najmanova—and stayed for good. Happily, this didn’t mean leaving his old life behind. In 1960, working with Feiffer, Deitch directed the first of his pet projects: Munro, adapting Feiffer’s indie-comics story of a preschooler mistakenly drafted into the U.S. Army. At once comical, vitriolic, and poignant, Munro won Deitch and Rembrandt an Academy Award for Best Short Film.

Enter entrepreneur William L. Snyder and his animation production company, Rembrandt Films. Deitch remembered Snyder as “a man who could talk anybody into anything.” He offered to fund Deitch’s pet projects if Deitch directed them at Rembrandt’s studio in Prague, Czechoslovakia, while managing the studio for Snyder in the process. Could Deitch adjust to life behind the Iron Curtain? As it turned out, yes; though Deitch’s contract established that he should “not be required to remain in Prague for a period of more than ten days,” Deitch promptly fell in love with production manager Zdenka Najmanova—and stayed for good. Happily, this didn’t mean leaving his old life behind. In 1960, working with Feiffer, Deitch directed the first of his pet projects: Munro, adapting Feiffer’s indie-comics story of a preschooler mistakenly drafted into the U.S. Army. At once comical, vitriolic, and poignant, Munro won Deitch and Rembrandt an Academy Award for Best Short Film.

Although Snyder famously took the Oscar under his own name, Munro’s success brought new American contract opportunities to Rembrandt. For producer Al Brodax at King Features Syndicate TV, Deitch’s team made numerous episodes of Popeye—among the first to introduce E.C. Segar’s comics character of the Sea Hag, but otherwise rendered in a King-mandated low-budget style. The same was true of Krazy Kat, another King series; but while Krazy reflected its budgets via slow pacing and rushed artwork, Deitch enjoyed the opportunity to more closely mimic George Herriman’s classic strip than had many previous Krazy Kat cartoons. Frequently serving as director himself, Deitch was required to turn Herriman’s androgynous Krazy into an unambiguous female, but he also transformed the maladjusted Ignatz Mouse into another of his trademark fanatics: not just a brick thrower, but an obsessive brick collector.

From Kat to cat, Deitch and Rembrandt took on their most famous assignment: the 1961 contract to revive Tom and Jerry theatrical cartoons for MGM. Series creators Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera were four years gone, having produced TV cartoons like Huckleberry Hound and The Flintstones ever since MGM shut down its shorts department in 1957. Now the department appeared to be open again, but the new films were no longer billed as being “Made in Hollywood, U.S.A.”; it was effectively Hollywood, Czechoslovakia, with Deitch’s staff in Prague Anglicizing their names for the films’ credits.

From Kat to cat, Deitch and Rembrandt took on their most famous assignment: the 1961 contract to revive Tom and Jerry theatrical cartoons for MGM. Series creators Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera were four years gone, having produced TV cartoons like Huckleberry Hound and The Flintstones ever since MGM shut down its shorts department in 1957. Now the department appeared to be open again, but the new films were no longer billed as being “Made in Hollywood, U.S.A.”; it was effectively Hollywood, Czechoslovakia, with Deitch’s staff in Prague Anglicizing their names for the films’ credits.

On some level, Tom and Jerry—like Howdy Doody and Terrytoons—was a property Deitch considered beneath his artistic level, or at least in need of an overhaul to gain his respect. “As a UPA man, I had always cited Tom and Jerry cartoons as the primary bad example of senseless violence.” But Deitch could not wholly deny that the Oscar-winning original had quality and merit—or that his Czech team had trouble measuring up, in part because MGM had slashed the budget by 75% from Hanna-Barbera days.

As Deitch’s team had personally viewed few of the original series, Deitch tried to make up for it by creating some layout drawings and key poses for the films himself. But a nakedly Eastern European music cue here, a peculiar facial tic there still showed that the new Tom and Jerry cartoons were not like the old. In some shorts, Tom acquired a grouchy human master reminiscent of Clint Clobber; in the legendary Dicky Moe (1962), Tom became the shanghaied ship’s-cat of a bellowing, muttering Ahab. In Landing Stripling (1962), Jerry befriended a Woodstock-like yellow bird with its own peculiar mutter, a constant, echoing burble like nothing heard in animation.

Gene Deitch only produced one year of Tom and Jerry, remembered by some fans mainly as peculiar—but by others as endearing, artistic, haunting and even subversive. The Simpsons’ cartoon-in-a-cartoon “Worker and Parasite,” framed as an odd Eastern European equivalent to its own Itchy and Scratchy, was inspired by Deitch’s Tom and Jerry films.

While MGM chose Looney Tunes’ Chuck Jones—at the time, lately laid off by Warner—to make the subsequent seasons of Tom and Jerry, Deitch quickly found a new opportunity with Paramount, this time producing an entirely creator-driven series. Nudnik, a neurotic and unlucky jack-of-all-trades, fronted 15 shorts released to notable acclaim from 1965 to 1967. Receiving an Oscar nomination with the first in the series, the bungling Nudnik became a kind of cult favorite, if not one of the top cartoon stars. One cannot help but draw a connection to his creator, who clearly preferred a seat in the counterculture to one at center stage.

As Nudnik receded, Deitch stayed in Prague and continued to produce and direct for Rembrandt. A generation of children’s book adaptations, released domestically in the USA by Weston Woods, included the first screen versions of J.R.R. Tolkein’s The Hobbit (1966) and Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are (1975). Deitch also directed Alice of Wonderland in Paris (1966): a compilation film featuring stories of James Thurber and Ludwig Bemelmans, framed with a story of Alice traveling to France not with a white rabbit, but a beret-wearing biker mouse. In 2004, Deitch won ASIFA-Hollywood’s Winsor McCay Award for his lifetime contribution to animation.

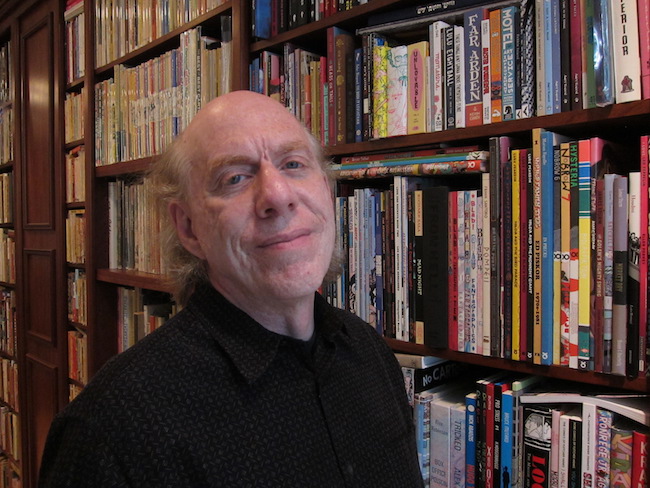

While for decades, Deitch looked back gruffly at many of his earlier cartoons, his negative feelings seemed to mellow over time; Deitch eventually embraced the home video release of his Popeye and Tom and Jerry shorts. “Gene was hard on himself,” says longtime animation historian Jerry Beck, who curated Tom and Jerry: The Gene Deitch Collection for Warner Home Video in 2016. “He was quite the perfectionist, especially when adapting other artists’ work. But he came to understand that many of the films he dismissed, back in their day, are treasured memories for many, and really quite good in their own right.” In recent years, Fantagraphics itself has released comprehensive collections of Deitch’s The Cat and Terr’ble Thompson; Deitch wrote lavish introductory material for us, eagerly getting back in the heads of his eccentric jazz fan and boy hero.

But perhaps Deitch, who passed away of age-related causes on April 16, 2020, might best be compared to his early Terry character Gaston Le Crayon. “You may hate what I create,” Gaston sang in his theme song, “but you must admit the artist’s life I live is great!” Reveling in counterculture for its own sake, Gene Deitch put a highly unique stamp on his entire oeuvre, spreading the gospel of exuberant modernism regardless of any setbacks he encountered.

Deitch is survived by Zdenka—his wife of more than 65 years—and his sons Kim, Simon, and Seth Deitch, all of them cartoonists themselves.