I can rarely remember where I was when I discovered any of my favorite cartoonists. But Abner Dean is different. On a summer afternoon in Charlottesville, Virginia, I went to a used bookstore near the University and headed, as always, straight to the cartoon/humor section. An oversized book’s black hardcover spine sporting the title Abner Dean’s Naked People stuck out from a shelf filled with beat-up paperbacks and small hardcovers with torn dust jackets. (It’d be cheesy to say that the book was “calling” to me, though that’s how it felt, or at least how I remember it). Opening the volume, I was instantly amazed — and puzzled. The drawings employed an elegant style I’d seen in pre- and post-WWII American magazines, but everything appeared strangely skewed, with nude yet de-sexualized characters, washed-out black and gray dystopian settings, and cryptic captions. The work radiated a peculiar aura, blending funny and sad with smart, provocative, and (oddly) inspirational. I quickly paid the seven dollar price penciled inside, left the store, and read it on the walk home.

I began searching for other collections by Dean as well as for his drawings and cartoons in books and magazines. I soon realized that he did hundreds, if not thousands, of commercial illustrations. Finding information on his life, however, proved far more difficult. Beyond the occasional paragraph in an encyclopedia of cartoonists, nothing. Dean seemed elusive, far less well-known and studied than he deserved to be. So I did some research that culminated in an “illustrated biography” of the artist published in Comic Art (#9, 2007). Some of that material made its way into a piece that appeared at The Comics Journal in 2014 and which, I was happy to learn, inspired the editors at The New York Review Comics to think about reprinting Dean’s work.

This month, they’ve performed a great service by rereleasing one of Dean’s best, 1947’s What Am I Doing Here? The New York Review version stays close to the original, with one significant change: the editors re-scanned the original artwork, which is housed in the Abner Dean Collection at Dartmouth College, the cartoonist’s alma mater. In celebration of the book’s release, my 2014 TCJ essay, much of which focuses on What Am I Doing Here?, reappears below. I hope it encourages you to check out one of the twentieth-century’s great cartooning philosophers.

______________________________________________________________

After years of reading Abner Dean, I still can’t answer a fundamental question: Are the drawings in the books he released from 1945 to 1954 cartoons? In one sense, of course, what we call them is irrelevant: they are beautifully drawn, thought provoking works of art. Yet the question gets at issues central to Dean’s philosophy and the trajectory of his career. Prior to releasing It’s a Long Way to Heaven in 1945, he had worked for over a decade as a commercial artist. Having drawn countless ads for products like crackers, cereal, and insurance, as well as hundreds of cartoons for popular magazines, he felt burdened by the limitations of contemporary cartooning formulas. Looking to create complex works of lasting value, in the early ‘40s he took the vocabulary of the single-panel gag cartoon — a genre he had long since mastered — and began producing “drawings” (his preferred term) that he thought of as something original, even “striking.” These innovations expressed his belief in the power of images, not simply to get a laugh, but to get readers thinking about themselves in new ways. The typical gag asks only for a quick chuckle at how we — or, more often, other people — act. But for Dean, the combination of image and text could stimulate a wide range of intellectual and emotional responses: delight, frustration, provocation, bewilderment, sadness, or illumination. To bring about such reactions, Dean created “cartoons” (a term he also used) that placed a greater demand on readers than typical gags and generated more questions than answers. Take Dean’s “Opportunist in a Strange Land”:

What’s the opportunity presented the protagonist? (To be a voyeur who can’t be caught looking?) Why don’t the others just remove the sacks from their heads? (Are they content in their blindness?) Why is he wearing a hat? (After all, no one can see it). But most importantly: What’s in his bag? If the opportunist represents Dean, then perhaps the bag contains, not his drawing materials, but a sharp pair of scissors: he can cut eye-holes in their sacks so they can see the world around them for the first time.

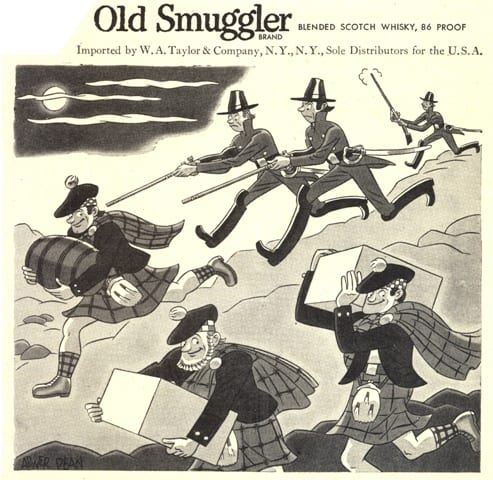

Dean released five collections that display the unusual approach to cartooning evident in “Opportunist in a Strange Land.” While mid-twentieth-century readers hadn’t seen cartoons like this before, they certainly had seen Dean’s commercial work in Life, Time, Newsweek, Esquire, Collier’s, Look, and dozens of other magazines.

Dean had a successful and varied career beyond cartooning; he collaborated on a ballet, lectured on psychoanalysis, published poetry, created animation for TV and Broadway, and appeared on TV as a game show panelist and cultural critic. His drawings show a similar eclecticism; he continually employs different mediums and styles, from silhouettes and woodcuts to aggressive brush work and a graceful, economical pen line. In what follows, I look at some of Dean’s most interesting mid-century work, art created by an innovative cartoonist celebrated during his lifetime as a “punch drunk prophet.”

*

1945 saw the publication of It’s a Long Way to Heaven, the first of four books (with What Am I Doing Here?, And On the Eighth Day, Cave Drawings for the Future) that solidified Dean’s reputation. These volumes represent an unusual achievement in American cartooning before 1960: unlike most collections, they feature cartoons that hadn’t been previously published, and they showcase a new and philosophical approach to the gag cartoon.

In 1941 Dean corresponded with a friend about commercial pieces he had sent to an exhibition at Dartmouth, his alma mater: “I hope Hanover likes the cartoons. Unfortunately they don’t represent my best work. I’m at work on a long series of drawings now that are not intended for publication.” It seems likely that this series, which Dean planned as a gallery show, became It’s a Long Way to Heaven. Seven of the collection’s cartoons first appeared in a 1942 Life magazine article on Dean, and these drawings (along with others in the volume) differ from conventional gag cartoons in two important ways: the text often appears within, or right against, the image’s frame; and the un-centered text is more like a painting’s/illustration’s title and less like a comic’s dialogue or narrative captions, which are almost always centered. (In later books Dean often placed text outside of the frame and often used type for the words — as did most gag cartoons — rather the hand-lettering of It’s a Long Way to Heaven.) Seminal literary critic Northrop Frye said of the collection’s cartoons that “the best have a disturbingly haunting quality that one rarely finds in the more realistic captioned cartoons of the New Yorker school, and in fact are ‘funny’ only to the extent of making one giggle hysterically.” Excited about the response to his daring work, Dean wrote that “advance reports from the salesmen are staggering — and the first edition . . . will be about 25,000.”

*

“The Efficiency Expert” (from It’s a Long Way to Heaven).

Dean was highly skeptical of specialized knowledge and repeatedly targeted “experts,” be they Freudians, philosophers, scientists, or even cartoonists. His drawings show people chained to books or wielding impressive-looking tomes as weapons in a competition for authority and a quest for self-affirmation. He believed we could only begin to achieve a sense of “balance” (a central concern of his cartoons) when we rejected others’ authority, questioned ourselves, developed a “plan,” and realized our inherent connection with other people. “Knowledge” and “facts,” Dean insisted, should be replaced with “doubt” and “wonder.” In keeping with his bias against metaphysical and moral belief systems (which he called “voo-doo ideas”), he never offered a detailed program for change: to do so would position him as an expert. In “You missed life” (from What Am I Doing Here? 1947), a man walks through an alley that houses a “pragmatist, “cultist,” “authority,” “expert,” and many others who have willingly labeled — and limited — themselves.

He attempts to rouse them into an awareness suppressed by their desire for what Dean called “the false security” of specialization. Next to the main character, a sign reads “stand in,” perhaps indicating that this provocateur stands in for Dean. Yet, will the sound of a triangle be enough to awaken them? Is this all the noise that an inventive cartoonist can generate in the world?

*

“The Understanding Wife” (from It’s a Long Way to Heaven).

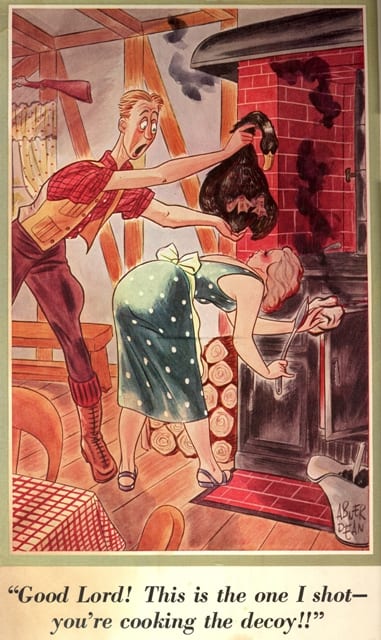

Dean’s commercial work from the early 1930s until the mid-‘40s often involved scenarios familiar in the world of men’s humor magazines, such as ‘the dumb female and smart male,’ ‘inscrutable woman and inquisitive man,’ and ‘domineering wife and subjugated husband.’

Scenes that use these premises appear throughout his 1945-1956 collections, and we may be tempted to see them solely as expressions of hostility toward women — but the work is more complex than that. “The Understanding Wife,” for example, appears to echo the third premise above: a husband is in thrall to a wife who, as the title ironically suggests, does not understand him.

In his notebooks, Dean often asked questions about a character’s self-awareness, and we could ask such questions here, ones that might affect our interpretation: If his wife doesn’t understand him, is it because he doesn’t understand himself or her? If she’s happy and he’s not, is it her fault? Does he look to her, not himself, for liberation from the stocks? Perhaps she understands the predicament he’s created for himself better than he does: “You are your own shackle,” Dean said elsewhere. In cartoons like “The bright young men” (It’s a Long Way to Heaven), “Party note” (Come as You Are), and many others, Dean criticized what he saw as males’ egotistical and destructive behavior, while in Cave Drawings for the Future he visualized the ways that men use women as metaphors for their own confusion, conflicts, and failings.

*

“I made this” (from What Am I Doing Here?, 1947).

Dean left five fascinating notebooks in which he wrote about dozens of cartoons from What Am I Doing Here? In this commentary he adopted different personas: in some he talked as if he were a character in the drawing; in others he sympathized with or scolded characters or readers in his own voice; and in many he offered either straightforward or obscure observations on his cartoon.

“Our hero is part fool-part wise man,” Dean said of “I made this,” “but for one moment he partakes of greatness — ridiculous as his creation may be it is better than the plodding absence of consciousness. Within its hectic form is a plan — is self recognition — in its fumblings is the hope —.” It’s easy to see this cartoon as ironic, mocking the immature artist. But Dean frequently felt sympathy for those who have a “plan” to create art or new ways of thinking that will, if only in some small way, make conditions better for themselves and others. At the top of his contraption is a magnifying glass: when we make or think about art, we can see the world more clearly and with greater precision.

Because cartoons in What Am I Doing Here? feature a recurring main character (“our hero”), the collection is more novelistic than Dean’s other books: it could be read as a kind of psychological picaresque narrative in which the hero progresses through an ever-shifting series of mental states and social dilemmas. Interestingly, the cartoons in this collection and elsewhere may have been inspired by a template Dean used in numerous ads he drew for Aetna Insurance, especially those of the early ‘40s. They feature a character in a state of crisis or error accompanied by an understated title/caption that addresses both the character and the reader, such as “Things don’t always turn out as you expect.”

Part of the interpretive openness of many cartoons in Dean’s books comes from the fact that the title/caption’s pronouns have many possible referents: An “I,” for example, could refer to a main character, secondary character, and/or Dean himself; and “you” could refer to a character and/or the reader. And titles often include “it” or “this,” either of which could reference any number of aspects of the drawing, or, in the case of “this,” even the cartoon itself. Many titles (which often are unpunctuated sentences) appear to be spoken by a character, but because Dean rarely used quotation marks, the text’s status as dialogue is also an open question.

*

“It’s good to own a piece of land” (from What Am I Doing Here?).

“Don’t search for hidden meanings in this drawing,” Dean cautioned. “They’re all apparent here — nothing hidden.” Like many of Dean’s titles, this one is to be taken literally: it’s good to own land and everyone should. Yet Dean criticized the smugness of those who fail to extend sympathy to people in need: “What about those other people — do they own any land?” Dean worried that readers might bring their own philosophical biases to this cartoon, warning that “there is no implication here that the state should own the land.” While many of Dean’s cartoons are cryptic, others communicate a simple premise in a transparent way, and Dean’s comments here offer a helpful reminder about over-reading and misinterpretation. If readers assume (as many have) that the cartoonist fails to sympathize with his characters’ plights, they are bringing their own cynicism — not Dean’s — to the drawing.

*

“Sometimes we give up too soon” (from What Am I Doing Here?).

“Competition on roller skates is my downfall,” Dean lamented. “It demands of me responses that are foreign — it’s not my fault — or yours. So I compete or withdraw. . . . Don’t talk of peace — of beauty — of culture of anything for that matter until we’re rid of competition.” Perhaps this cartoon expresses not only Dean’s general antagonism to competition, but his distaste for the commercial art world in which he was entangled, as one cartoonist among thousands competing for the scraps of advertising budgets. Dean’s views on competition intersect with, and were likely inspired by, his interest in psychoanalysis. Many readers have argued that Dean is heavily indebted to Freud, but I think his cartoons are more Adlerian than Freudian. Alfred Adler, one of the three main figures of modern psychoanalysis, believed each of us suffers from an “inferiority complex” that drives us to compete with others to establish our sense of self-worth or superiority (Dean called Adler, Freud, and Jung “The Id Kids”). Like “Sometimes we give up too soon,” dozens of Dean’s cartoons feature a character in a struggle with other people for self-definition. Following Adler, Dean argued that “self-actualization” would occur only if we rejected competition and embraced cooperation. Dean and Adler were less inclined than Freud to look to a person’s past or to sexually-based complexes for the source of neurosis. Adler believed that we based our lives on what he called the “fictional finalism,” an idealized self-image that we rarely understood but nevertheless spent a lifetime trying to achieve — Dean’s drawings repeatedly show a lone character wandering through a vast and barren landscape on a quest for such self-realization. Taken as a whole, his cartoons offer a thoughtful examination of the psychology of personal identity and social interaction that draws on numerous philosophical traditions. (Using slides of his cartoons, Dean lectured about psychology and psychoanalysis at colleges and medical schools, and his publishers noted that his cartoons were used in psychiatric practice.)

*

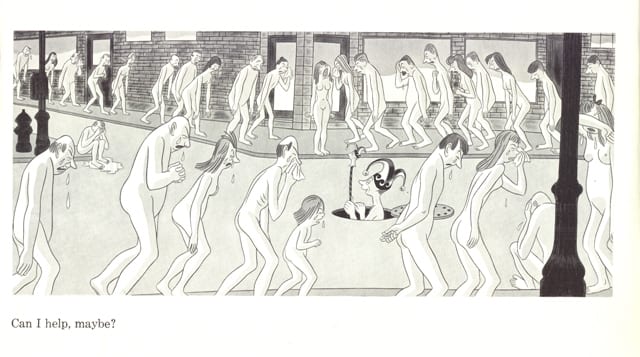

“Can I help, maybe?” (from What Am I Doing Here?).

In picturing the jester as small, tentative, and seemingly powerless when confronted with a mass of suffering people, Dean may reveal an ambivalence toward his career as a satirist. Although his goal is lofty — arousing those who sleepwalk through life — most expect from a cartoonist only a fleeting, lowbrow laugh, the kind Dean often delivered in his earlier commercial work: “I’m a rare one when it comes to lightening the moment — anyone got a lampshade I can wear as a hat — this’ll kill ya!” Dean also wrote about this cartoon that, although “humor never cured anything,” “rightness . . . [will] have a twist of real humor in it,” perhaps the kind of philosophical twist so often found in his drawings. The jester emerges unseen from the manhole, as if from the depths of the weeping characters’ collective unconscious. Though he can’t cure others (Dean believed you can only cure yourself), he can help them become happier and develop a deeper understanding of their own condition. Echoing his admiration for the artist of “I made this,” Dean praised the jester: “it’s better to try than just to ignore.”

*

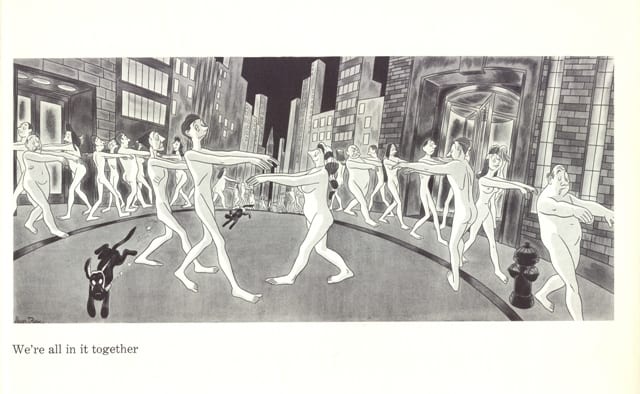

“We’re all in it together” (from What Am I Doing Here?).

Dean: “It’s to the good that one eye is open somewhere in this somnambulistic scene. Beware of mad dogs — sleep walking minds. This isn’t dream world stuff. You can snap this with an ordinary Brownie any day. Pose Please! He’s beginning to be conscious . . . it may be contagious. . . . Meanwhile our hope is that we’re all in it together — just that. No one is separate. There’s an old wives’ tale that it’s dangerous to waken sleep walkers. Dangerous? More dangerous than what?”

*

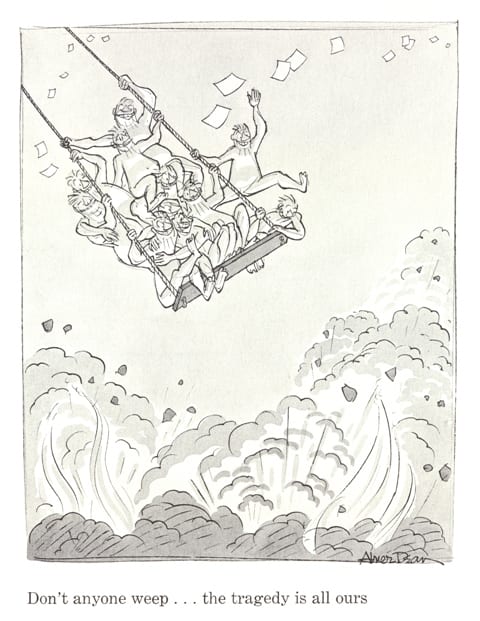

“Don’t anyone weep . . . the tragedy is all ours” (from And On the Eighth Day, 1949).

In each of the seven books released from 1945 to 1956, Dean used a different visual style. The art in And On the Eighth Day has a loose, deliberately unfinished look that contrasts with the polish of his earlier volumes and commercial work. A reviewer attacked Dean’s cartoons as “vitriol martinis” and Time magazine criticized this collection as “a grim search through the weird subconscious levels of John Doe, a search that altogether misses heart & soul but finds a spirit crushed and shriveled.” The claim of pessimism is more accurate for this book than previous ones, not because the content is darker, (though it occasionally is), but because the style is harsher: Dean’s line is far more angular and aggressive. In particular, characters’ faces are often reduced to a series of quick marks, erasing the individuality they possessed in previous cartoons. Reviewers and readers who have described Dean’s oeuvre as “grim,” though, have overlooked the ways that the grace and charm of drawings in other collections bring a lightness and humor that mitigate the content’s darkness. I wouldn’t say Dean was never pessimistic, only that his emotional, intellectual, and visual range show more far more complexity and artistry than any term, or even set of terms, could capture. His work embraces a kind of cryptic optimism and slanted psychological insight that I continue to find inspirational.

*

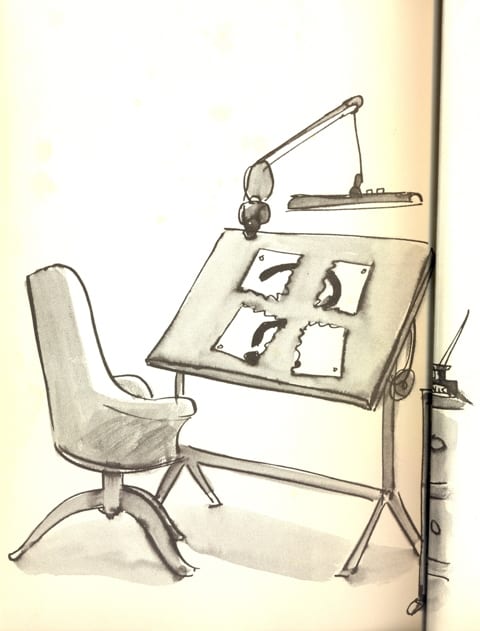

Born on March 18, 1910, Abner Dean died on June 30, 1982 in New York City, the place of his birth. The last piece in his final volume of new material is an illustrated poem titled “Very Late Afternoon Thought.” Dean drew an empty chair in front a drawing table with a cartoon of a question mark torn into four pieces:

What is there

Will not be me –

I will have left there

Quietly

On exit cue

With cartoon done –

And you can sit and watch the fun.