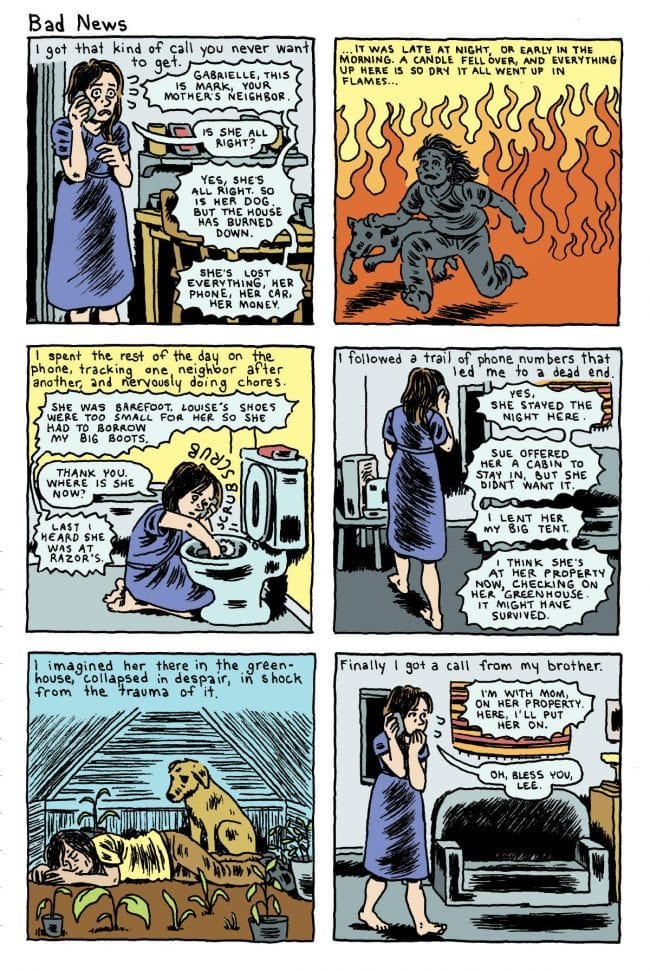

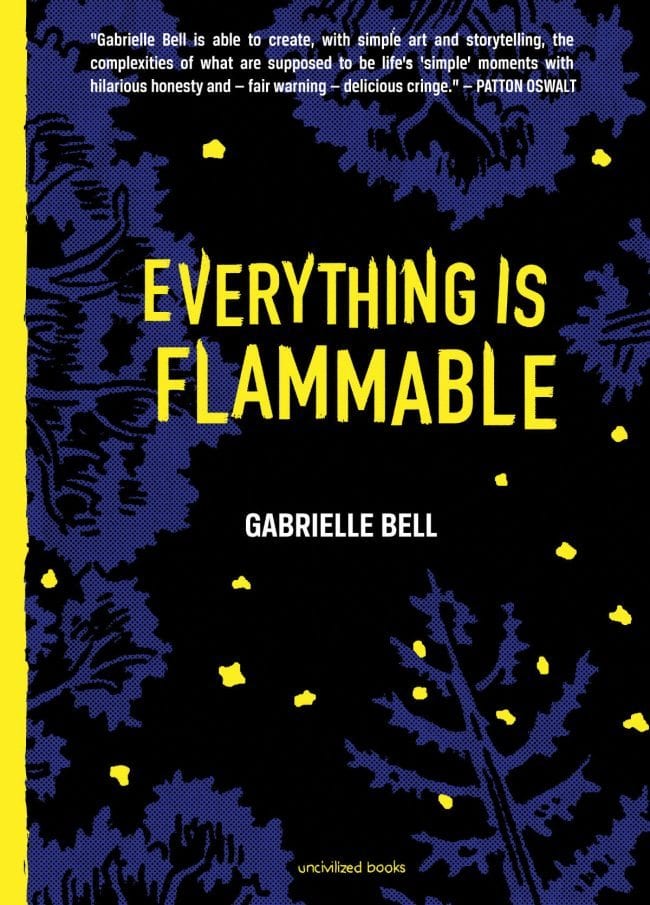

Everything Is Flammable, cartoonist Gabrielle Bell’s latest graphic novel for the Minneapolis publisher Uncivilized Books, follows Bell as she helps her mother rebuild a life and a support system after losing her Northern California home to a fire. Bell treks from her house in upstate New York to the California woods, encountering many human and animal characters along the way. I spoke to Gabrielle about diaries, metacognition, and more, over the phone from her apartment in Brooklyn.

Everything Is Flammable, cartoonist Gabrielle Bell’s latest graphic novel for the Minneapolis publisher Uncivilized Books, follows Bell as she helps her mother rebuild a life and a support system after losing her Northern California home to a fire. Bell treks from her house in upstate New York to the California woods, encountering many human and animal characters along the way. I spoke to Gabrielle about diaries, metacognition, and more, over the phone from her apartment in Brooklyn.

Interview edited and transcribed by A.M.

ANNIE MOK: When you were getting started putting this book together, what was the organization of the material like? How did you decide to start and finish where you did?

GABRIELLE BELL: I have to admit there was not a lot of organization. It started from… the event...

MOK: With your mom’s house burning down.

BELL: My mom goes through a lot of things and this was pretty terrible. It kind of woke me up out of the self-absorbed tunnel of my life. So I had to go and help her out a bit, or even just be there with her. But I wasn’t so self-involved [laughs] that I wasn’t going to make comics about it. I just started sort of keeping a diary, but more just collecting stories. At some point I collected enough that it would make a book.

MOK: At least one of your minis for Uncivilized consists of roughly drawn diary comics. What’s the difference between the diaries and the finished product for you?

BELL: Mostly I keep a diary every day. Then I'll take one of those entries and turn it into a more refined story. I’ll stop keeping a diary while working on a story. And I would sort of lose the connection to the source of the story. I always have to break it down and go back to the roughest version, which is the diary. I go through cycles. Sometimes I don’t keep diaries at all because I get so absorbed in the one part of it. Or I'll get this standard in my head where I think the diary has to be a refined story, to look like a the finished product. I always get to some point where it doesn’t have any spontaneity anymore, [laughs] so I have to let myself be bad at it again. Let it be boring and awkward and have no point again, to get back to the raw data of it.

MOK: With this book or with your books in general, is there an idea or feeling or intent you’re trying to convey to the reader?

BELL: I just want them to be engaged. My ultimate goal is just to make people feel good. I suffer from all kinds of depression and anxiety and a lot of people do. I just want to give a good feeling to the reader. But I want to work out my own issues too [laughs].

MOK: Self-talk and metacognition play a big role in your comics. In one part [of Everything Is Flammable] you’re like, “One night I got the shame attacks. ‘I’m such a jerk. Stop calling yourself a jerk, you jerk!’” How does this kind of self-talk find its way into your comics?

BELL: It’s just a learned behavior. In that particular story, it was me and my mother trying to deal with things that is really a kind of man’s world, dealing with negotiations and business and planning to build this home. Both of us have relied on men in the past and it’s kind of gotten both of us in trouble. It’s put us in this sort of helpless situation. So we were out of our element. And I think, being women too, there’s a husband or the father in our heads saying we’re doing it all wrong. In the story, my way of coping was to sort of flirt with the guy, and manipulate him in my way, while he’s sort of manipulating me. I am trying to play up this vulnerable female role with him and my mother, putting on this image of “We’re just helpless females, we don’t have any money.” "We don’t have these skills of being assertive and manly [laughs] and the art of the deal. So we work with what we have." The shame attacks at the end just came from feeling ashamed of myself for being manipulative and also just relying on other people, like my friend Sadie, to stay at their houses. I mean, this is all normal stuff. People rely on each other and help each other out. But in this story we were both being forced to get out of our comfort zones.

MOK: There’s a lot in the story about men, and you talk about how in films mothers are portrayed in a negative light. You say, “Mine exists outside of that continuum.” You talk about navigating those kind of liminal spaces.

BELL: I’m very sensitive to mother-blaming. I think the most liberal among us… And father-blaming to. I did that too when I was younger, thinking “I didn’t get what I deserved” and stuff, and now… I’m very sensitive to people complaining about their moms not doing enough for them. Because of the difficulties that any mother has, we should be grateful that they were there at all. I mean, I know some people who had really abusive mothers, that’s sort of different.

MOK: Yeah.

BELL: But even in that case, our parents are really just children. There is this thing of motherhood, just the very word… I don’t see her as my mother. I mean, she is my mother, but I just see her as a person who comes from Michigan, travels in Europe for a while, and then settled down in California, where had some really bad boyfriends [laughs], and then had some kids, and then the kids moved away, and then she made a life of her own in California. I don’t see her in relation to me, like what she owes me or what I owe her.

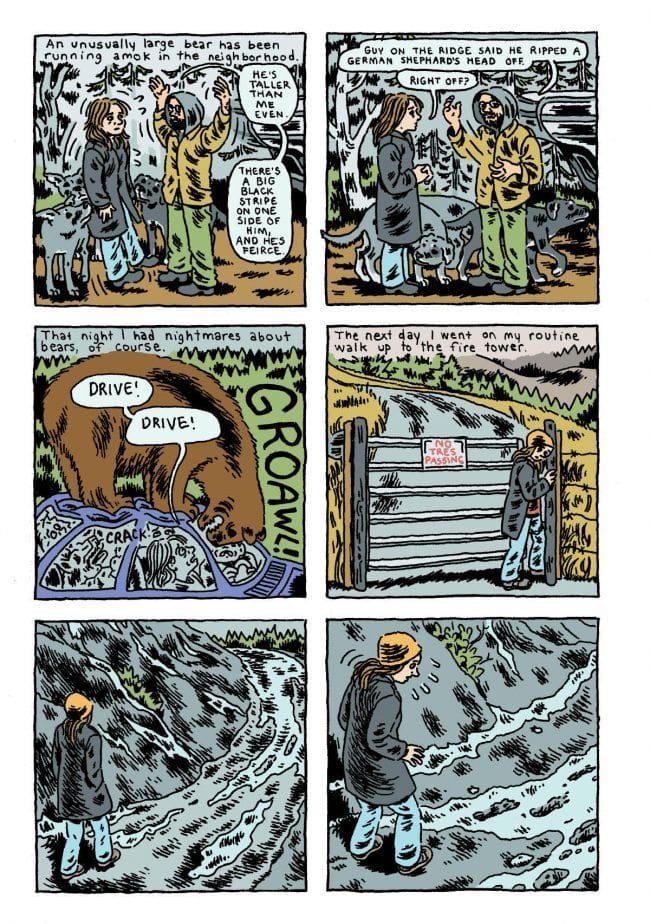

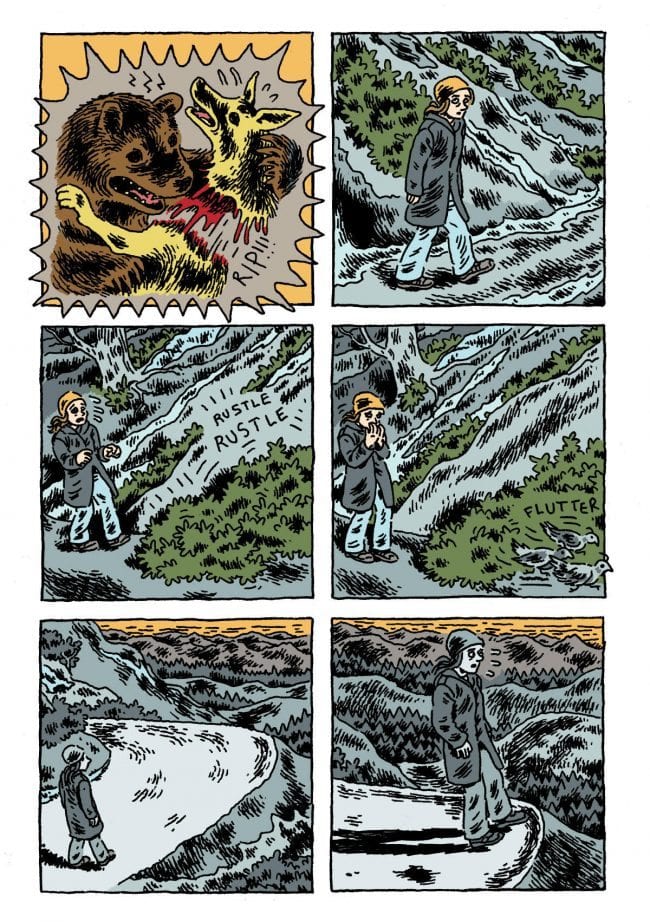

MOK: It’s interesting that you’re back in Brooklyn ‘cause there’s so much about your relationship to the city, you mention that you could feel like Lou Reed living in a run-down apartment; and then there’s this contrast between that and the woods, and all the plants and the animals you encounter out there. What does your relationship to the woods and animals bring to your work?

MOK: It’s interesting that you’re back in Brooklyn ‘cause there’s so much about your relationship to the city, you mention that you could feel like Lou Reed living in a run-down apartment; and then there’s this contrast between that and the woods, and all the plants and the animals you encounter out there. What does your relationship to the woods and animals bring to your work?

BELL: I do really miss living up north, I had a nice yard and I could garden in the summer, and the air was so much more pleasant, more breathable. Even in the winter, when it snowed, it was so beautiful. When it snowed in the city it’s so ugly. I needed the artistic community, to be around other cartoonists. Everyone I knew up there was married and with kids; I mean, they were artists, but I was like this weird single lady up there [laughs]. And I was restless, I wasn’t ready to settle down. I am definitely happier to be back in Brooklyn. I live in a building with some cartoonist friends and I live down the street from [cartoonist] Ariel Schrag.... Turns out you can’t have everything. I mean, if you were rich, I guess. I’m happy to be back in the city, even though I’m depressed here [laughs].

MOK: Aw!... You talk in this book about intergenerational storytelling. You talked earlier about how our parents are just kids, and you have this conversation in the book with your grandmother about her mother. How do you see your place in this link of intergenerational storytelling? You’re now the person telling these stories.

BELL: First of all, I don’t think it was right that I was so hard on her that night. I think I was angry at my mom and then I took it out on her mom. In the story, I’m like, “No more children, I’m not having children,” but I think that’s just because I didn’t want to have children. Not because of the damage done, I guess. I think if I wanted to have kids, it would be, “My kid, I’m gonna raise my kid differently!” But I think it’s just that I’m more of an artist, and I want to do my art and focus exclusively on that. Also, I think that my grandmother and my mother—this is really jumping to conclusions and making assumptions—I think they, probably, it wasn’t their first choice to have kids. It was just a generation, it was expected of you. It wasn’t, “Maybe I don’t wanna have kids, maybe I wanna go to the sea and be an artist or something.” I think I sort of inherited this disposition of not wanting to have kids. Which is kind of interesting, because this disposition resolved itself by ending that generation.

MOK: Speaking of your art, as always you make a few fantastical leaps in your comics. There’s one page where you show your mother living as a mermaid because of this Marilynne Robinson line. Can you talk about making those leaps and what those bring to your comics, those fantastical jumping-off points.

BELL: I don’t think there’s quite so many in this book...

MOK: Yes, there’s much less, which I was curious about.

BELL: The other one [in the book], there’s one where I had this fantasy that I married this guy who lives on my my mom’s property. Then I changed my mind and imagined her marrying him! That was kind of practical fantasy, in a way [laughs]. It didn’t have to do with love, “If I married him I could stick around, and be there for my mom, but if she married him that would even be better because I wouldn’t have to stick around and she’d have somebody to take care of her.” Sometimes I worry about getting boring and just want to dabble it up a little and have a flight of fancy. Sometimes if things get heavy, I wanna make a little fun.

MOK: There’s even some fun ways you visualize anxiety, you show it as a creeping vine, and then there’s the ghost cats.

BELL: That’s also the beauty of comics. That’s one thing that comics can do very easy. It makes the whimsical solid and concrete.

MOK: I’m curious how you negotiate what goes in the comics. Obviously, there’s very personal details about everybody. Do you have conversations to negotiate what stays or what goes?

BELL: Not necessarily. The one interview I did with the guy who was in prison for some time, I was specific with him. I changed his name and ran it by him to make sure there’s nothing that would make him uncomfortable. I didn’t want to incriminate him or anything. There’s a real serious drug culture up there, but that wasn’t what I was interested in, and… It’s pretty legal now, marijuana cultivation, but there is a paranoia still. Having grown up there, it was extreme and very justified paranoia—a lot of fear and secrecy. Even though it’s getting more lax now, there’s the habit of paranoia and secrecy. As far as personal things, I was pretty liberal with my storytelling. For the most part, I was like, “Can I put that in a comic?” I felt like I was being pretty kind to everybody. I wasn’t maligning everyone, so I just hoped that people would be okay with it and would understand that I was celebrating them. Though I don’t know about that crazy guy on the bus. There was a few people that I don’t know what they’ll think of it.

MOK: What’s it like putting out books with Uncivilized? You’ve put out several books with them now and it seems like you have a good publisher relationship.

BELL: Yeah, it’s really good. Really good line of communication. I’ve never been able to communicate so well. Maybe it’s because we were friends before. It’s always been really great with [publisher Tom Kaczynski], I’ll tell him how I want the book to look like, and then he’ll say “How about this?” and then we’ll compromise… I feel really part of the process. I feel like I’m being helped along and at the same time I get a lot of say.

MOK: Speaking of the design, how did the chapter headers come about?

BELL: I think I just wanted to fatten it up a little [laughs], have some filler. I think it helps the story breathe a bit.

MOK: You draw people and places really vividly. Are you doing life drawing at all, or is it straight on the page?

BELL: I took a lot of photos. I do it the way I always do, which is half photographs, and half memory or impression. I did a lot of photographing because I knew this would be a story, like I’d go on a walk and run into this dog barking at me, and think, this seems like a story. It’s more to remember what they look like, not really to draw from life.

MOK: I was like, “God these dogs are all really specific!”

BELL: That was a lot of work [laughs]! That kind of drove me nuts. But I felt like they needed to have specific personalities.

MOK: I really like how the book ends. You end with “Have you seen this dog?” with this dog that’s walking around, and then there’s a short bit about Gus having built a bathroom onto this new house, and you taking a bath. How did you decide to end the book this way?

BELL: I don’t know if anyone would notice, but it felt to me like he was building this thing that I had dreamed about, him putting a big extension on the house. So it was a realization of a fantasy in a way. I was so happy he’d did that. It seemed to me that it showed he really cared for [my mother], saying “I don’t want her to bump her head on the ceiling,” so he went the extra mile and manipulated the boards and did some fancy carpentry so she wouldn’t have to duck her head. So that was really striking. It really was a nice bathroom, it was really luxurious [laughs]. Like a classic sort of hippie bathroom, homemade. So I wanted to end on a good note. Incidentally, he built another room onto it and a porch. I haven’t seen it since it’s been built up. I didn’t really know how to end it. I knew there was sort of a catharsis, and all this emotional stuff with my mother and my grandmother, and the story was sort of over, you know? There’s like in a story, there’s a climax, and the stuff that happens after that where it fully comes to an end.

MOK: You bring up care, it reminds me of what you said earlier about what you wanted to leave the reader with. There’s so much about care and vulnerability in all your books”—there’s the scene with the woman having a seizure and you’re trying to help her, and there’s the scene with your mother’s dog who’s having a panic attack. I’m curious about the role of care and vulnerability in your stories, and also how you’re depicting it, because you depict it very subtly.

BELL: There’s one thing, I just have this weird urge to help older ladies. When I see an older woman who’s vulnerable… maybe because I see my old mother in them or something. I have not always been as caring as I am now. I used to be pretty callous I think. Growing older, you get more sensitive to other people. And when you have anxiety problems and depression problems, it’s easy to not care about other people because you’re wrapped up in your own pain. But I sort of, I guess, made more of an effort to be aware of other people’s pain. Not always successfully. That’s where I get shame attacks too, maybe I was insensitive to someone else’s pain. I used to get anxiety wondering what other people thought of me, now I get anxiety worrying that I might have hurt somebody. So there’s a little progress [laughs].