Near the end of last year, a friend told me that Frederik Peeters had come out with a new book called Sandcastle. I was already a fan of his graphic novel Blue Pills and realized that it had been ten years since its original French release from Atrabile. It seemed like a great time to ask Peeters a few questions about his comics and himself.

This interview was conducted by email between November 2011 and March 2012.

ERIC BUCKLER: It says in the author information in Sandcastle that Pierre Levy had met you in relation to a Blue Pills movie. Can you tell us any more about that?

FREDERIK PEETERS: Pierre Oscar is a movie director, especially of documentaries. Something like seven years ago, he contacted me to put an option on the rights of Blue Pills. He then came to meet me in Geneva, and he filmed some interviews with me and my family for preparatory work for his project, and we became friends. Unfortunately, years passing by, it wasn't possible to make the movie, because of financial reasons. But we kept on seeing each other, and one day, he said he had written a graphic novel scenario especially for me. I answered I wouldn’t do it, because I wanted to work on my own stories, but I accepted to read it. And so it appeared obvious to me that I had to draw it, the story was so good, the characters, and especially this central very simple and yet brilliant idea. It was kind of inspired by the Luis Buñuel’s movie El Angel Exterminador, but Pierre Oscar upgraded it in something more vicious and metaphysical, with a touch of the B-series.

BUCKLER: You start this book much in the same way as Blue Pills, there are close-up, or maybe nondescript panels that end up being parts of a beach, but at first could be anything, like the cellular drawings in the beginning of Pills and also the first panels of your series Lupus. What was your intent?

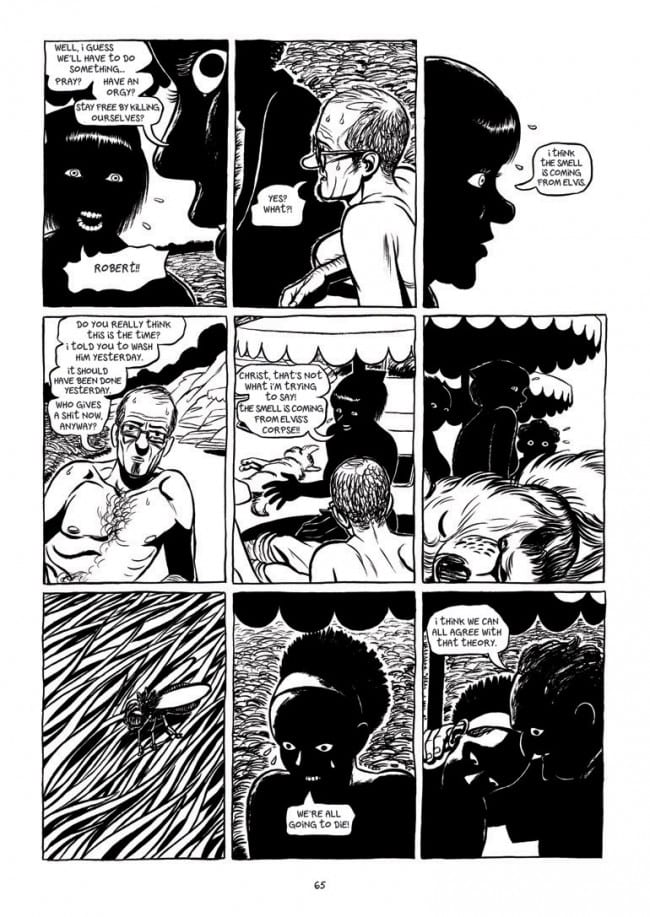

PEETERS: The reason concerning Blue Pills and Lupus is very simple. It’s because they are improvised. I mean, I really don’t know what I am going to draw and tell when I grab the first page. I know the subject of course, the autobiography of a part of my life, or science fiction, and I have a vague feeling of how to start—a context, maybe the main character—and the rest comes while I am drawing strange abstract images, like drawings you make when you’re on the phone. It’s a way to start the engine, if you like, it allows to open a door in the brain. Concerning Sandcastle, it’s different. I wanted to make the reader feel that, starting from a distant overhead, he’s entering slowly a closed area he couldn’t escape from. And yet, the whole background is there from the beginning, the water, the cliffs, the plants, the sky. The story is about a lot of characters stuck in a place, and the physical movements between them are rather complicated to organize in a comic strip language. It’s something more theatrical, so it’s necessary that the reader has in mind a clear view of where they are and how it is built right from the beginning.

BUCKLER: On several pages in Sandcastle you include little snippets of beach life like jellyfish and fish and environment. What made you stop at those specific points and place those throughout the book?

PEETERS: First it‘s a way to put rhythm in the story, give the feeling that time is passing. It’s one of the only ways I have to do it, because everything happens in one single place with no trace of civilization or technology, and I cannot show something outside of that environment. Also, I cannot fill every frame of the book with the characters. I use the changing of light, the moving shadows, and of course, the sun. And second, it’s obviously a way to show that nature is in the center of the story, or more precisely, the relationship of man and nature, and who is the true master in the game. Pierre Oscar says the core of the book has something to do with the Promethean destiny of mankind, global warming and environmental crisis.

BUCKLER: Did you use brush on Sandcastle?

PEETERS: Yes I did. Pentel cartridges brush. It’s my favorite tool. I’ve worked with pen and ink, watercolor, pastels; I’ve tried many things. Brush is fast, convenient, sensual, and it has something smooth in the lines but quite difficult to tame at the same time. Otherwise, when I draw sketches in my notebook, I generally use a pen with a straight metal point

BUCKLER: Did you use specific people as models for the beach characters? If so, who were they, and why those people?

PEETERS: Yes, I used some friends, some children around me, and also Jacques Attali, a famous French intellectual, as the SF writer. It was convenient, because all the characters had to be very strong and different from each other, always in order to clarify the reading process. They all had to be clearly alive in my mind, I had to know their way of thinking, the way they move etc… I had to relate to thirteen characters, so it was much more easy to use people that already exist. I chose them according to how they were depicted in the script. For instance, the father that first appears in the book seems to have ecological preoccupations, so I used the face of a friend of mine who has the same preoccupations. And Jacques Attali is very often ridiculous and has opinions on everything, so it was ironically funny to give his face to the writer.

BUCKLER: How did you go about applying the aging process to the characters?

PEETERS: That was the most challenging and exciting part of the work. Usually, in a graphic novel, characters are always the same, and the backgrounds are always changing. Here, it’s the complete opposite. I just made a lot of sketches before I started. It was quite easy to age those who were already adults, adding some lines, digging the faces, making the bodies softer and heavier, removing some hair, but it was quite difficult to draw the children as adults, because we change a lot during the teenage years, and I had to be sure they would stay recognizable. Also, they had to look a little bit like a mix of their parents.

BUCKLER: This is the tenth anniversary of the original Atrabile Blue Pills. Can you talk about how you feel towards the man you depicted yourself as in those panels ten years ago?

PEETERS: I don’t think this way. The present and future seem more interesting to me. In this book, it’s exactly me, but ten years younger. It just shows that people evolve. But I’m totally concentrated on my actual projects, I’m not very nostalgic.

BUCKLER: Are you still with Cati [the HIV-positive woman Peeters depicts a romance with in Blue Pills]?

PEETERS: Yes.

BUCKLER: What is the presence of HIV in your world today?

PEETERS: We’ve had a little girl, HIV negative, eight years ago. Cati's son is going to be 15. With the evolution of treatments, I can say that fear has almost disappeared from our lives. It’s still sometimes difficult for her to live with guilt, but I will not talk in her name. All I can say is that we have the same everyday and existential problems as every middle-class occidental parents… We are much more preoccupied with years passing by, the future of our children, and the meaning of life than with HIV.

BUCKLER: Have you gotten feedback from readers who are familiar with HIV?

PEETERS: Not particularly. It’s more a book about a love story than about HIV. I never presented it this way. The strangest experience I had was a phone interview with a journalist in Korea, who was stunned by the fact that a man could talk so freely about his intimate feelings. We didn’t talk at all about illness, she just wanted me to give some advice to the readers on how to be happy in love. A bit like a special adviser, or a guru if you want. Totally surrealistic to me…

BUCKLER: What kind of feedback do you normally experience from fans, and I guess the comics community in general?

PEETERS: Honestly, I don’t know. It appears that a certain amount of people like what I do. Some journalists tell me nice things, but aren’t they telling nice things to every artist? And some readers talk to me when they wait for signatures, but usually, they are very silent. And I cannot say I’m the kind of man who’s fishing for compliments. Everyday work is the only thing that counts. Even if I must say that when I get a gentle message, like the other day, from Guy Delisle, saying that Aâma is great, it is very pleasant.

BUCKLER: When you met Cati, it seems like you experienced a profound level of life changing things all at once; love, proximity of a major illness, parental emotions, sexuality. How did that change you? What was your brain like before and after Cati?

PEETERS: Again, I don’t see it that way. You know, luckily, I had experienced sexuality before! The problem is that, when you read the book, everything is organized, compressed and amplified. My goal is always to offer a reading experience, something that makes you think and feel complex emotions, not to make a realistic documentary. In reality, the whole process, the meeting, the questions, everything took a lot of time. It might be like when you experience real war, opposite to movies like Apocalypse Now. The real war must be slow, sometimes boring, even daily. But now, with detachment, I can say that this encounter forced me to make a series of choices and decisions, and therefore to become an “adult.” But you know, millions of people make very difficult decisions everyday, and nobody notices it.

BUCKLER: What is more of a challenge for you: working from your own story, or working on something written by another?

PEETERS: Working on my own stories, definitely. Because I don’t write the story before, so I have to write and draw in the same time. And it’s emotionally more demanding, because I can’t help myself putting a lot of my life and fears in my stories.

BUCKLER: Why do you feel like comics are a good home for a personal narrative like Blue Pills?

PEETERS: Because there’s no interference between the artist and the reader. It goes straight from my brain to the brain of someone else. There’s no actor, producer, technical or financial problems. You can play with visual symbols, silences and face expressions, which is impossible in literature, and yet, it involves a reading process that works like a mirror in which the reader puts his own emotions, unlike cinema, which is a more dictatorial form of art. Everybody tends to see the same spectacle in cinema, in graphic novels, the reader is part of the creation, so it’s perfect for intimate stories centered on human aspects.

BUCKLER: There is a theme of mortality and a sort of sickness that the characters in Sandcastle have at the beach, one that makes death appear quicker than expected. Did you use any of your experiences with the world of HIV as the "Rhino" in the room?

PEETERS: No, I cannot say that. I’m not the author in Sandcastle. I see it more like metaphysical fairy tale if you like. The reader is not much involved as in Blue Pills, where you live things through the main character point of view. In Sandcastle, you’re more like a distant spectator. Blue Pills talks about two persons, Sandcastle talks about the whole world. But you could say that the aspects that appealed to me in the Sandcastle script, the deterioration of the flesh, time, what we do with our lives, why and who you desire and love, couple as an antidote to loneliness, etc., are already present in Blue Pills. But I guess they’re present in all my books, because they’re present in my head.

BUCKLER: What is on the horizon for you as far as projects you can tell us about?

PEETERS: I started a science fiction serial story called Aâma. The first volume was published last year by Gallimard. Each volume is 84 pages long, the format of the original drawings is huge, I also do the story and the colors. It’s a big adventure saga, with a lot of characters, a gorilla-robot named Churchill, big fights, but also family intrigues, and some philosophical questions about time, transhumanism, the status of technology in our lives. I’m totally dedicated to it, and it’s gonna last a few years.

Sandcastle is available from SelfMadeHero in English. Pachyderme will be published in English translation by SelfMadeHero in September 2012.