Frank Thorne, one of American comics’ finer craftsmen and more notorious personalities, has died at 90. A cartoonist’s cartoonist whose career covers much of the comics medium’s midcentury history, Thorne’s bibliography runs the gamut from sober family-friendly newspaper strips to transgressive hardcore pornography, all delineated with the steady hand of a master illustrator.

Frank Thorne, one of American comics’ finer craftsmen and more notorious personalities, has died at 90. A cartoonist’s cartoonist whose career covers much of the comics medium’s midcentury history, Thorne’s bibliography runs the gamut from sober family-friendly newspaper strips to transgressive hardcore pornography, all delineated with the steady hand of a master illustrator.

Born in 1930 to a working-class Rahway, New Jersey family, the youthful Thorne harbored an irrepressible creative urge, touring both as a jazz trumpeter and a stage magician. Cartooning was also deep in his bones, spurred by a childhood love of Alex Raymond, whose feathering inkwork and fetishistic treatment of pulp storytelling tropes in Flash Gordon would be a career-long influence on Thorne. Breaking into the comics profession at age 17 with a scattering of romance and superhero strips for publishers like Standard and Fawcett, Thorne had inchoate careers in comics and music going well before he graduated from Manhattan’s Art Career School. In the post-WWII era of Thorne’s maturity and marriage to wife Marilyn, cartooning provided the steadiest source of employment available to the young jack of all trades, and with the diligence of a born family man Thorne devoted himself to the comic book field.

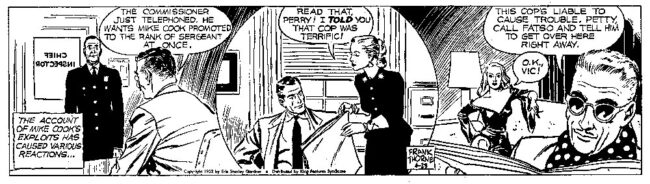

By 1952 Thorne had landed the Holy Grail of comics jobs - a syndicated newspaper strip, King Features’ daily Perry Mason. It was well earned: the young Thorne’s work was unostentatious but rock solid, with grounded figure work and an instinctive balance of black and white space, as similar to Roy Crane’s minimal action cartooning as Alex Raymond’s fanciful phantasmagorias. Thorne’s early work compares well to contemporaneous comics by Alex Toth, with crisp lines and a streamlined sense of design giving his strips the ability to build up momentum in a couple panels. But the constant grind of producing a strip a day and a color page on Sunday wore heavily on Thorne, and after a few years he regarded King’s cancellation of Perry Mason as a blessing. Back into comic books Thorne dove, finding steady employment on action strips at Dell – Flash Gordon, Green Hornet, and adaptations of Tom Sawyer, Moby Dick, and the like. The Perry Mason experience had given Thorne one clear leg up – unusually for a commercial cartoonist of his era, he penciled, inked, lettered, and colored most of his jobs, allowing total control over the visual character of the books he worked on.

Thorne’s career meandered in a not atypical fashion for a decade, winding through commercial illustration gigs, another stint on a syndicated strip (Dr. Guy Bennett, mercifully free of a Sunday page for most of Thorne’s run), and more comic books. Thorne had by this time built up the desire to script a work of his own creation, but such opportunities were rare in the early ‘60s, and scripts from others were plentiful enough to allow his growing family a comfortable life. Still, Thorne was developing into a singular talent. The debut of Dell’s Mighty Samson, written by science fiction author and superhero scribe Otto Binder, allowed Thorne to design a visual world from the ground up. While the book’s stories are typical comic-book hokum, the verdant flora Thorne bedecked Samson’s post-apocalyptic New York in provides an uncommonly vivid visual experience. Samson “made drawing comic books all the more seductive,” and after a seven-issue run Thorne hopped from cameo to cameo in books like Boris Karloff Tales of Mystery, mixing in illustration work for venues like the Little Golden Books line while he waited for another shot at a feature series.

It would come at DC Comics, losing ground to Marvel but still the industry’s top publisher in the late ‘60s. Thorne’s style had grown more rendered and rough-hewn as he moved away from newspaper strips, and its similarity to that of Joe Kubert, star artist of DC’s non-superhero books, made him an excellent fit for the company’s war line. Thorne settled in with writer Bob Kanigher for a long run drawing the Revolutionary War-set adventures of frontier ranger Tomahawk, informed by a longstanding interest in the colonial period. When Kubert took over the book’s editorship from Murray Boltinoff, Tomahawk became the Western Son of Tomahawk, and Thorne’s career in comics had its first bona fide highlight. Son of Tomahawk, aided by Kanigher’s searing scripts, conjured an Old West ruled by the twin American original sins of racism and violence, and starred an early biracial hero: Hawk Haukins, son of Revolutionary War hero Tomahawk and his Indian wife, a youth adrift in a dangerous world with no place for people who look like him. Thorne rose to the challenge of Kanigher’s passionate stories, illustrating the book’s tight family cast and barren Western settings with powerful verve.

Son of Tomahawk stands up as well today as any early ‘70s comic, mainstream or underground – but the book only lasted 10 issues, and Thorne went along with Kubert to DC’s Tarzan line, illustrating the spin-off Korak, Son of Tarzan. A 1976 move to Marvel gave Thorne’s career another signature moment, and this time it was a hit. The Conan the Barbarian spin-off Red Sonja, drawn by Thorne with a perfect balance of cartoon realism, Gothic shadow, and bawdy humor, was lauded by a fanatical cult audience. Reinventing himself on the fly, Thorne embraced the culture of fandom at the dawn of the age of comics conventions, doing more than perhaps any other comics creator to establish cosplay as a cultural force. Judging lookalike contests in his guise as the long-bearded “Wizard”, and creating Sonja-inspired costumed dramas, Thorne and a series of buxom, scantily-clad models performed for comics conventions, public access TV — and eventually, the Playboy Channel.

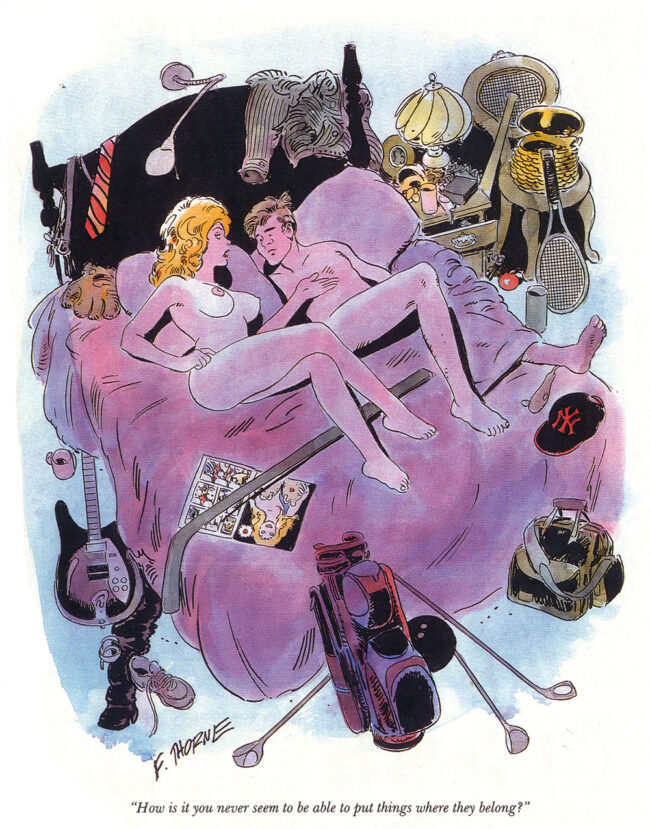

After Sonja, having found a pleasurable and lucrative aesthetic niche, Thorne created genre-inflected soft porn for venues high and low, becoming one of Playboy's frequent gag cartoonists while creating a steady stream of unrepentantly sleazy comics. Few venues for “adult oriented” comics in the ‘80s went without a Thorne cameo appearance of some kind. Risque heroines in the Red Sonja mold, but free of Marvel’s content restrictions, popped up everywhere: Heavy Metal featured sexy spacegirl Lann, National Lampoon carried pneumatic trail guide Danger Rangerette, Playboy ran the Li’l Abner spoof Moonshine McJugs, and in 1984 he published Ghita of Alizarr, a barbarian warrior whose blonde tresses were all that kept her from being a carbon copy of Sonja.

Easy to lose in the flurry of porn Thorne batted out in the ‘80s was that he was part of a wider trend: the movement toward creator ownership of concept and art by veterans of a midcentury comics scene famous for leaving its keenest strivers destitute once anyone who could do the job quicker or cheaper came along. But where many artists who’d spent careers on nothing but commercial pabulum struggled to free themselves of old habits once a chance to do whatever they wanted had been won, Thorne settled comfortably into an idiom where there was always money to be made. Though it always carried a noxious whiff of objectification and outmoded gender typing, Thorne’s porn was largely good-humored, with cute and naive characters desperate for pleasure usually finding the happy endings they were looking for amidst genre tropes made softly farcical in the new context their artist gave them.

A 1990 compendium series from Fantagraphics’ porn line Eros Comics, The Erotic Worlds of Frank Thorne, collected highlights from his ‘80s strips and led to a long association with the publisher, then much in the business of giving grand old men of the midcentury comics industry a platform for less-commercial work – especially when naked women were prominently featured. But Thorne was no hack drafting off past glories to make a saleable product of halfhearted masturbation fodder. Ever the dedicated craftsman, his career in porn comics chronicles a continued refining of his style, which moved from slashed Kubert-esque rendering to a lusher, inkier simplicity that made perfect sense next to European erotica masters like Guido Crepax and Georges Pichard in the “Adults Only” section of ‘90s comic stores.

Thorne’s notoriety as a smut merchant crested in one of those Adult sections with the 1995 seizure of his atypically hardcore Eros book The Devil's Angel from Planet Comics in Oklahoma on (quickly dropped) charges of child pornography, placing the impressively bearded senior citizen in good company with NWA, Dungeons and Dragons, the Dead Kennedys, and outlaw cartoonist Mike Diana as victims of the '90s' benighted culture war on youth-corrupting media. Spun off from earlier series The Iron Devil, The Devil’s Angel is a strange book, full of physical transformations and effluvia, with the kind of bizarre vision that can only be legitimately personal in nature counterpointed by its author’s glossy, commercially appealing art. In its more outré passages it resembles a modern version of Chaucer or the Decameron’s debauched anecdotes, complete with ham-fisted sociopolitical satire and rather charmingly dated sensibilities. Outside Oklahoma, at least, Thorne’s lascivious content never really crossed over into the realm of the truly offensive.

As his professional career wound down, Thorne’s goofy, slightly antiquated sensibility propelled enough Playboy gags to keep him far from the poorhouses so many of his contemporaries in early comic books spent their final chapters in. He engaged in memoirs of his youth with the Fantagraphics releases Drawing Sexy Women and The Crystal Ballroom, allowing a florid prose style free rein over expressively penciled spot illustrations. At 90, still a happily married New Jersey family man, Thorne continued to bat out large-format soft porn imagery in his round, deceptively simple mature style as well as uncharacteristically large-scale abstract paintings. Considered in total, his career arc is one of those bewildering, loopy zigzags best described as "only in comics". An American original, Thorne passed away on March 7th, 2021, followed into the beyond only hours later by Marilyn, his beloved wife of seven decades.