Today, when you’re ingesting the latest whirl of supremely controlled, cold-as-ice pages from Michael DeForge, or finding yourself having lost forty-five minutes cracking up knowingly while scrolling down Kate Beaton’s Tumblr, it may hit you how strangely natural this feels. You might also look in the mirror and catch a fleck of gray hair, and then perhaps experience a residual sense of alienation.

Because, yes, it has been about twenty-five years since those heady days of comics suddenly—again—appearing like they were all promise. Yes, there had always been great comics and much ground had been broken in previous decades, but there was a crackle in the air in the early nineties. A sense, when you opened a new comic, not so much of a blank slate, but rather that those clear lines, those scruffy hatch marks were composed fractally of unrealized potential. At that moment, everything seemed (theoretically) possible. Precariously, but exhilaratingly so.

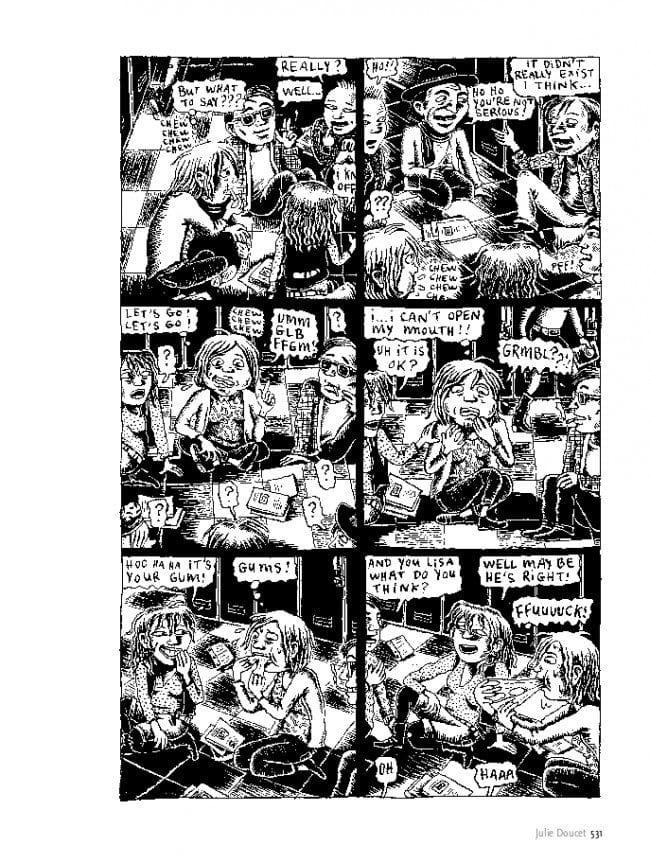

And yes, Chris Oliveros’ Drawn and Quarterly was there, somewhere near the center of this breaking kaleidoscope. A fledgling publisher in hip Montréal, sufficiently shrewd—and lucky—to launch out with a handful of the finest cartoonists of their generation: Julie Doucet, Chester Brown, Seth, and Joe Matt. It may be obvious today, but the gauntlet they threw in the face of comics was radical at the time: a look at real life.

It did garner the publisher a reputation among reactionaries for publishing exclusively navel-gazing autobiography, which it took more than a decade to shake, but that was less due to any real predictability in their publishing line than it was to the shock of the new. Autobiography and other reality-based approaches to comics became the natural locus of the quiet explosion of tradition that was happening in comics.

D+Q was part of a bigger movement, of course. We in Europe watched seminal publishers such as Amok, L’Association, Atrabile, Cornélius, Edition Moderne, Ego comme X, Fréon, Galago, and Reprodukt rewrite the rules, while in North America the only house that could consistently hold a candle to D+Q was Fantagraphics, the publishers of this website.

It is hard not to compare the two, and in some ways it is helpful. Although united in purpose, and despite increasing overlap of cartoonists published, the contrast between the two publishers is marked.

Fantagraphics’ Gary Groth, Mike Catron, Kim Thompson, and Eric Reynolds were always more of an eclectic outfit, combining an acute—at times combative—critical sensibility with an affinity for the American undergrounds, a reverence for comics history, and an ahead-of-its-time devotion to European cartooning. Each of them a strong personality, they have followed their individual interests and generally placed great trust—sometimes to a fault—in the artists they publish to handle their own product. This has resulted in a bibliography which stands beside any in comics history, but also one without a great deal of internal coherence, which has at times suffered from inadequate promotion and lackluster design and production.

D+Q, perhaps naturally for what was a one-man operation the first many years, has always had more of a distinct profile: gentlemanly, aesthetically refined if also somewhat conservative, dignified and literary with a tinge of nostalgia. Also less profligate in its output and, especially with the arrival of Peggy Burns as publicist in 2003, more astutely run in terms of marketing and promotion. At its best, these factors enable highly sophisticated work to flourish, at worst it means somewhat predictable, “pretty” and rather earnest but ultimately dull comics. In any case, it is a significant feat that the publisher, despite actually handling widely different artists, continues to make every book fit the portfolio.

Though clearly a strength, this at times means that artists come across as somewhat more bourgeois and palatable than they actually are, or might wish to be. At the very least, it might steer them in that direction: it seems natural, for example, that Fantagraphics still handles Gilbert Hernandez’ increasingly transgressive and aesthetically challenging episodic work, while he publishes more neatly groomed—though still excellent—graphic novels with D+Q.

Several factors contribute to this, but among the most important has been the relatively small, tightly knit core of cartoonists identified with the publisher for the first decade or so, as well as Oliveros’ ability to integrate their particular tastes and preferences into his own, and to encourage their community building and interest in comics history. D+Q is not only a promoter, but also a creator of artistic lineages in cartooning, something to which the current publishers, Peggy Burns and Tom Devlin (hired as production manager in 2004), have also contributed in crucial ways.

From helping foster the close friendship between Brown, Seth, and Matt that developed in the early days and quickly became an integral component of their work, to facilitating Adrian Tomine in his rediscovery of Yoshihiru Tatsumi. From connecting individual cartoonists with their historical paragons on exemplary reprint projects—Seth with John Stanley and Doug Wright, Chris Ware with Frank King—to establishing links in the readers’ minds that no one may have realized were there: Tove Jansson and Ron Regé, Jr.; Seth and Dupuy and Berberian and Penti Otsamo; Chester Brown and Anders Nilsen; or even Jason Lutes and Shigeru Mizuki, or Mizuki and Michael Deforge at that.

And perhaps most crucially, to recognize in new generations cartoonists with congenial sensibilities or related concerns: publishing Geneviève Castrée makes total sense for a publisher who started out with Julie Doucet and Debbie Drechsler, distinct as their work is, as does gathering Robert Sikoryak and Kate Beaton under one roof. And giving new hope, and creative life, to an artist as aesthetically distinct and deeply invested in drawing from life as Lynda Barry as they did some years ago, when she was floundering in a publishing environment that did not appreciate her, seems like a no-brainer today. And then to publish Brecht Evens.

All this and more is what is being celebrated in the publication under review here. Edited by Devlin, with Oliveros, Burns, and others and clocking in at 776 pages, it can best be described as a catalog of the publisher’s merits, sensibilities, and history, but also—and importantly—a Festschrift to the artists it has published. Tastefully, attractively, and accessibly edited and designed to the uniformly high standards of the publisher, the book does this job extremely well. The amount of quality material between its covers, and the enthusiasm with which it is presented, almost chases away the sense that one is reading a giant product catalog.

The leading historical essay with attendant timeline, by Sean Rogers and Jeet Heer, is informative and rich in anecdote, but low on critical assessment. Nary a word that is less than complimentary is uttered, and little effort is made to analyze the greater shifts in cultural consumption or the aesthetic developments in comics that enabled D+Q's success, and to which the publisher in turn contributed so significantly. But this is, of course, not an academic treatise, nor is it a piece of critical inquiry. It's a giant advertisement that very successfully makes the reader enthusiastic about the artists and books published by D+Q, and rightly so, because there is much to discover, or rediscover.

The book combines selections from almost every cartoonist associated with the publisher for the last twenty-five years, along with written appreciations of many of them—some authored by broadly recognizable figures such as Margaret Atwood, Jonathan Lethem, and Lemony Snicket, others by fellow cartoonists or critics in the know. Additionally, it assembles a wide array of vintage photographs and other documentation of D+Q's history as well as interviews with, and personal reminiscences from, many of the people involved.

Most of the comics material is both representative and of high quality. Some of it is quintessential, or just plain masterful: John Stanley’s restrainedly expressive Tubby story "The Dispossessed Ghost" (1954), a hilarious tale of childhood fears; an eloquently oneiric hymn to youth, "Street Performer", by Seichi Hayashi (c. 1970); "Chantal" (1991), Dupuy and Berberian at their romantic best; David Mazzucchelli’s vivid and disquieting "Rates of Exchange" (1994); Adrian Tomine’s most successful essay in punchy Lish-Carveresque poignancy, "Pink Frosting" (1995); Debbie Drechsler’s yearningly poetic "The Dead of Winter" (1996); Gabrielle Bell’s moving encapsulation of hipster alienation “Cecil and Jordan in New York” (2005); and James Sturm’s smart, cuttingly brief, and predictably controversial online imputation of the current generational shift in comics culture, “The Sponsor” (2014).

Others turn in interesting new, or rarely seen work: Chester Brown’s beautiful quasi-Biblical “The Hymn of the Pearl”, issued as a minicomic for his friends in 2009 (and marred here in by an ugly orange caption box running across the bottom of the last spread, one of the few design screw-ups in the book); an all too brief excerpt from Chris Ware’s unpublished intriguing-looking “Joanne Cole”, intelligently juxtaposed with sketchbook pages suggesting how he uses life drawing in his comics; a new account by Kevin Huizenga of his own future career that sees him neurotically becoming almost cosmically aware; a similar, yet completely different and sneakily powerful comic by DeForge; a funny “Wilson” strip by Dan Clowes from The New Yorker (2010), which is not included the graphic novel; Robert Sikoryak doing Walt Whitman à la Jack Kirby; a gorgeous and characteristically moving account by Geneviève Castrée of different kinds of blankets she has slept under. Plus new work from Joe Matt (!)

The excerpts from longer, career-defining works, such as Jason Lutes’ Jar of Fools (1994) and Dylan Horrocks’ Hicksville (1998) work less well in this context, but still present classic work. Plus there is inevitably work that will leave a given reader cold. Not every artist in the D+Q stable is equally great, of course, but the book contains surprisingly few real duds, as in work that seems unwarranted in this context or is unrepresentatively sub par. This is an impressive editorial accomplishment when presenting that many different contributions between two covers.

The book is a reminder of past glories to be sure, but one that leaves one hopeful for the future of one of comics seminal publishers over the past quarter century. It reminds one of the path trod to get from there to here, the new “normal” in comics.

The hope, of course, is that D+Q will continue to publish quality comics and to play an important role for a new generation of readers looking for what’s next. There is reason to be optimistic. Oliveros has now stepped down as publisher to concentrate on his cartooning, leaving it in the hands of Burns and Devlin. But he seems to have so successfully, albeit deceptively quietly, asserted his sensibility there, and in comics more generally, that it has taken root and in a way that accommodates a vastly expanded field of artistic approaches and temperaments, some that if one steps back would have been hard to imagine at D+Q when he was starting out. And yet it feels natural.