If there's a better argument for comics than Catherine Meurisse, I don't know it – and the French clearly agree. They've officially made this year "2020 Year of the Comic" and Meurisse is one of three artist-sponsors named by the government. She will work with pioneer Florence Cestac, co-founder of the publishing house Futuropolis, and Jul, who created the best-selling Silex & the City. In addition, on 17 January, she became the first comics artist ever elected to the country's prestigious Académie des Beaux-Arts.

There are serious aims for the 2020 Year of the Comic and French Culture Minister Franck Riester has announced its fundamental initiatives. To aid aspiring authors, there will be a new, national competition as well as fresh distribution, exhibition and publishing schemes. Comics will get a boost as part of the country's heritage, too, via funds for purchasing, preserving and exhibiting original art.

Another goal is to make Paris the "complement" of Angoulême. The French capital already has its own comics festivals, events like Pulp, So BD, Formula Bula and Bédérama. But Riester wants Paris to get its own comics centre – so he intends to build one. He's also adding comics to the government's 'Culture Pass': a smartphone application that offers 18-year olds 500 euros of "cultural capital". (The Pass facilitates free access to theatres, concerts and museums, as well as credit towards the purchase of books or instruments.)

But the most critical focus for Year of the Comic is improving the lives of creators. In France, the production of BD keeps expanding; it grew 9% over the last twelve months. In this book-obsessed country, bandes dessinées comprise 11% of all the publishing and more than 5,000 titles appear each year. Yet, as Riester notes, the bright figures hide a more complicated story. "At the same time as we have all this growth, far too many auteurs are questioning their choice of profession. Most of their problems arise from day-to-day realities."

He has appointed a pair of task forces to help with that. One is charged with assessing the métier's "specificities". Mid-autumn, they are due to report – with a list of better ways to help creators. The other group will suggest changes that should be made to artists' taxes, their social protections and pension provisions. The government is determined, Riester maintains, to shore up the "social, economic and cultural standing" of BD and their artisans.

These are big promises – and he'll be judged on the outcome. Many, including one of the BD's biggest talents, Marion Montaigne, are insisting that action mean action.

There are other, more aesthetic, reasons such a "Year" makes sense. If I had to choose a work that embodied them, it would be Delacroix by 2020's new Patron Catherine Meurisse. Touching on friendship, liberty and creativity, it is a story that moves between witty cartooning and swathes of ravishing art.

Catherine's co-author is Alexandre Dumas (1802-1870), who also penned The Three Musketeers. But their book's subject is Eugène Delacroix (1796-1863) – the famed Romantic painter who was Dumas' lifelong friend. Almost all the text is an 1864 talk Dumas gave, something he called the Causerie sur Delacroix.

The 19th century "causerie" was an informal, informative, chat. Although written, it was delivered live – almost performed. Dumas wrote his to open the retrospective held in Paris a year after Delacroix died. Meurisse ran across it as an art student. Although she bought the book on a whim, she was delighted by its portrait of a life in art.

This chance discovery became her art school thesis. Working only with black-and-white, she hand-copied the Causerie. She cartooned its anecdotes and caricatured its protagonists, adding irreverent versions of Delacroix's famous works. What resulted was droll and inventive and, in 2005, Switzerland's Éditions Drozophile published it.

By the time it appeared, Meurisse had a job. She went to work at Charlie Hebdo where, for nine years, she was the only female artist. She spent twelve years at Charlie, while producing comics on the side. In albums such as 2008's Mes hommes des lettres (My Men of Literature), 2012's Pont des Arts (Bridge of the Arts) and 2015's Moderne Olympia, her protagonists were artists – figures like Picasso and Proust, Zola and Monet. She treated them as cheekily as she had Dumas and Delacroix.

Then came the January 2015 attack. Meurisse, late to work, escaped by minutes. But it killed twelve of her close friends, left eleven others maimed and changed the artist's life forever. When she resurfaced, it was with an album called La Légèreté ("Lightness"). A mix of anguish, reminiscence and parody, it recounts the fight to reconstruct her life. In it, Meurisse once more sought – and received – help from friends like Proust.

Her next book was Les Grands Espaces (The Great Outdoors), which has just appeared in English. It tells the story of how Meurisse and her sister grew up in the country. But it's also a poem, a survival manual and a consideration of childhood itself.

Meurisse finished it in Japan. She was there for four months, working on a project about writer Natsume Sōseki. As she was drawing the book's final pages, something struck her. "I was showing my younger self fascinated by orderly gardens, that classic French tradition you still see at Versailles. I had myself installing a gnome to serve as my 'classical statue' – then I depict my garden growing out of control. My little 'French garden' becomes a kind of jardin anglais, a Romantic landscape filled with weeds and ruins. It made me stop and think, 'What kind of metaphor is this? What does it mean to start with the rational then end up gravitating toward Romanticism?'"

When Meurisse has a question, she consults the experts. So, to decode this unconscious drift, she went back to Dumas and Delacroix. By that spring, when the Louvre unveiled its blockbuster show of the painter, she was turning the Causerie into Delacroix.

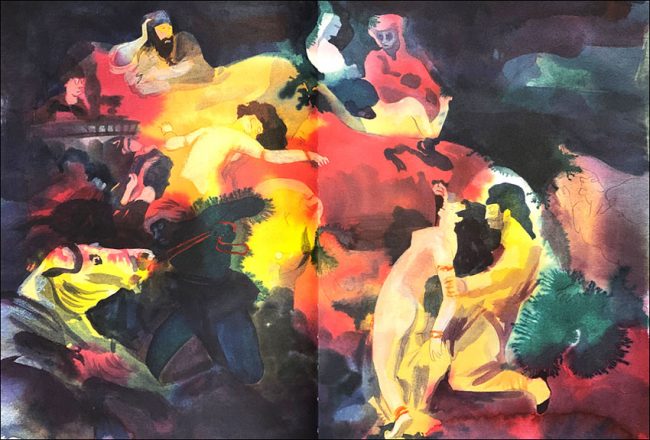

The result is more than the artist's best work. It's a demonstration of how much a BD can do. Augmenting Dumas' chatty text with bits of Delacroix's diary, she paints a rich portrait of two friends and their era. She also charts the history of Delacroix's iconic painting Liberty Guiding the People. It's a story rife with comic potential, which Meurisse exploits with consummate skill. What takes your breath away is her volume's visual freedom, the ingenuity of its montage – and its delicate beauty. But I may have buried the lead: it's hilarious.

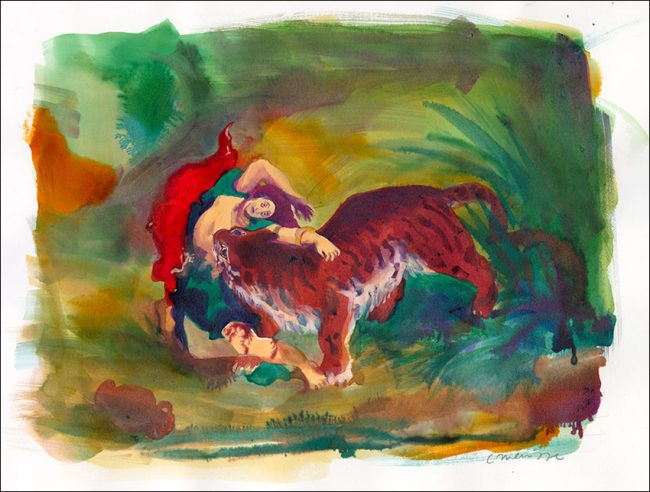

Delacroix himself replaced classic rigor with color and exoticism. His adventurous choices made painting more modern, more expressive and more personal. But the ammunition he used is the stuff of B-movies: rearing stallions, half-naked slave girls and battling tigers. (There were few things he loved more than a rotting corpse.) Yet, whereas Dumas was an easy-going bon vivant, the man behind all the harem girls was uptight and conservative. When he painted in front of people, Delacroix kept his coat on.

His Liberty Guiding the People is a Cinemascopic affair, an homage to the French Revolution of 1830. Yet its emotional sweep has made it a painting about the whole idea of revolution. Meurisse takes this lofty classic down a peg – by making its bare-breasted Liberty one of the story's characters. Liberty pouts, stomps and sulks across the pages.

Delacroix has many such inventive strategies. But the book's true achievement is one of synthesis: it creates a really different way to tell a story. It succeeds in being, at one and the same time, dramatic and exuberant, touching and rib-tickling. (The more you know about art the funnier it will be.) Without trying to make its historic figures "just like us", Delacroix communicates what they have to share.

The recipe for such an accomplishment wasn't simple. It took fifteen years of work, friendships and experimentation. It was also forged by the trauma of 2015 and the sort of sufferings you wouldn't wish on anyone. Yet it is one of the most original comics in decades – and I wanted to ask Meurisse about it.

***

How does it feel to share a byline with Alexandre Dumas?

It's great! Because Dumas was just so good at what he did. He developed a recipe that carries the reader along while still teaching some history. I've met so many people – not all of them French, either – who've learned about our past by reading The Three Musketeers or The Count of Monte Cristo. You learn but you never feel like you're reading a textbook. Dumas tells his stories as if he's sitting beside you.

It's that quality I loved in the Causerie, this very generous and still resonant voice. It made me feel just as free as he had been, that voice. I wanted to do the same thing, to tell Delacroix's story. But I wanted to do it with drawing, line and colour.

For a long time now, I've drawn all the artists I love. I haul them down off their pedestals and make them part of my family. By now, I really feel like they're my brothers and sisters. So putting my name next to "Alexandre Dumas" was like a wink at my personal history. Although these are people from you can find in the grandest history books, I think we need them next to us on a daily basis.

What, beside the tone of his text, inspired you?

I was inspired by 19th century painting, by the era's caricatures – and by photography. Because we know how Dumas and Delacroix looked, there are wonderful photos of them. Before the first Causerie, I studied all of that. But I never had the sense I was 'illustrating' something out of the 19th century. It was something that was very present today.

That woman, that Liberty is guiding the men, she's a true heroine and totally contemporary. I really love that. When I went back to the Causerie in 2018, of course I went to the Louvre, I saw the actual paintings. But more than anything else, I felt this desire for something deeply flamboyant and colorful. So I didn't dive back into all my early research; I relied more on my memory and the impression all the works had left.

It was like I was working from memory, like things were a little fuzzy and I needed my glasses. In that kind of artistic blur, I could let myself stay free. That way, I was unencumbered by academicism– or the specific politics and histories. Visually, I also wanted to use things like jump cuts and montage.

That actual era – it's very complex. It's hard for today's reader to grasp all the social change, all the upheavals those artists endured. It was a truly turbulent era and Dumas was immersed in it, he was close friends with a lot of political movers. What I found interesting is how, in his text, he simplifies. He simplifies all the stories and events and histories… so we can really follow and understand. Yet it never becomes lightweight or narrow.

He tells the real story behind "Liberty Guiding the People". How you handle that is really funny, but it's also poignant.

Well, Dumas did much more than just concoct a eulogy. He talked about all Delacroix's faults and all the problems he faced, as well as the trouble he had expressing his feelings. Not to mention Delacroix's politics! Because, even then – after the painting – people talked about him as a radical and a Republican. Some critics wrote that, in Liberty, that tall guy with the rifle is a self-portrait. When, of course, Delacroix wasn't remotely radical. On the contrary, he was quite conservative.

As Dumas says, Delacroix created a painting that was far more militant than he could ever be. Although, as I put in the book, he did write his brother that if he never fought for his country, at least he could paint for it... This was all part of what I liked. Because when artists take refuge in their own little world, when they're in front of their easel or at their drawing table, they think only about what's in front of them. It's when the work is finished and it's out in public… That's when it falls to us, the readers and viewers, to discover what's really in there. I have more trouble with the 'militant' artist whose work is thought out ahead of time to be militant.

I like that Liberty ended up much, much more radical than Delacroix. I like the idea of works that are greater than their makers, works that transcend their creators.

The book is…delicious. It has a wonderful poetry.

Back in 2016, when I brought out La Légèreté, several people told me there was a kind of poetry there. It was the first time I ever heard anything like that. Then, with Les Grands Espaces, it was a bit the same… In fact, the first draft of Les Grands Espaces had started out with me as a child reciting Baudelaire. But I had taken it out, because it made what I wanted to do too literal. Instead, I decided it was up to me: I had to make the book itself a poem about where I grew up.

So I didn't decide to put poetry in my books, it just arrived by itself – to my surprise. Because when you've been a comic cartoonist for such a long time, poetry is the last thing you expect to find in your stories!

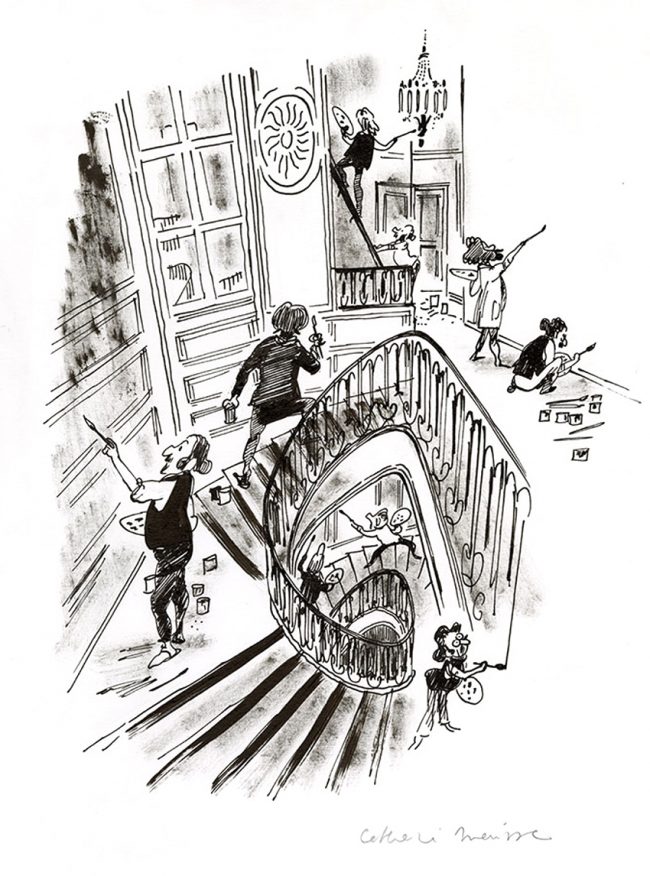

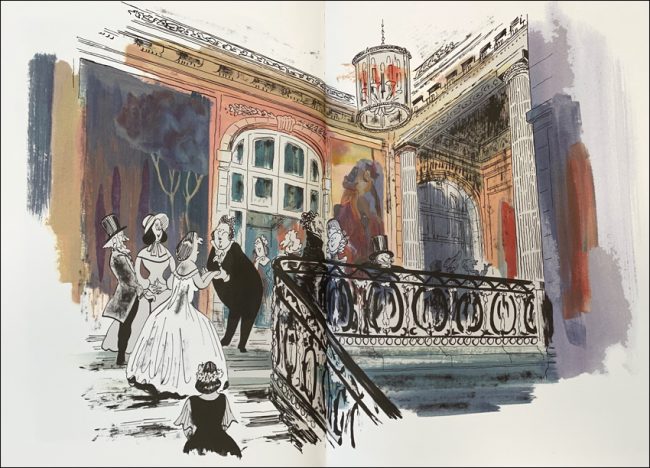

One of the unexpected things in Dumas' text is his emphasis on artistic camaraderie. Especially in his anecdote about throwing a costume ball. He decides to hold this party and he has his artist friends decorate all the walls. After a dozen years at Charlie, did that strike a chord ?

Absolutely. The whole idea of artists who sit side-by-side, who draw and work together, who are battling together for something … We had that same kind of sharing and sparring. Dumas uses one phrase I really love – he talks about the "sainte fraternité dans l'art"… "art's hallowed fraternity". I adore that expression, to me it's really the stuff dreams are made of. Everyone there at work, drinking and laughing and painting at once. The whole idea of an artistic construction site… Where, in the book, you see Delacroix with all these artist friends around him. Still, of course, wearing his little redingote, that dandy's jacket he didn't want to shed. Also that description of how he just starts painting, without ever making a sketch. He's a real prodigy.

I think I'm always trying to surround myself with texts and authors who tell me stories of friends who work together. Because that's what Delacroix is; it's really a book about friendship.

Today, the bande dessinée has festivals and salons where they try to set up that same kind of thing. Sometimes they manage to do it but it's not a natural thing, it's more a kind of theatre for festival-goers. The artists, of course, are happy to do it. They love meeting up and they love to work like that. But the kind of solidarity in Delacroix is different. It's something one just has to have lived. It's a day-to-day thing that becomes a part of your life, something natural like we had at Charlie. These days, it's at all not easy to have that.

Those 19th century artists worked at a frenetic pace. Yet the demand for change now is much, much greater. There's a non-stop quest for novelty all the time.

Today is an individualistic age, very brutal. On Instagram, we're each running our own publication and we're all on show. But all these gimmicks are really bankrupting the work. People type everything today. But that's not writing, of course it isn't. Real writing, real art – to create that takes a great deal of actual listening, a great deal of real looking and a great deal of time. Social media is the very opposite of spending time that way, it's just wasting time. Today's media wants to keep us immersed in the immediate. You're meant to always be getting ahead… to be à la mode before la mode even exists.

I'm not going to criticize the whole of social media because it can help me show my work and I use that. But I find it pernicious because, when it invades our lives, it becomes catastrophic. To spend all one's time staring at a screen, to live with a screen always in front of you, always between you and the world….to live so all your communications pass through a filter… it's a disaster.

When you prefer taking a photo of a piece to actually looking at it, it deforms what you're seeing and distorts your gaze. It ruins almost every aspect of the work and you unlearn what you know about seeing. That's my impression and so what if people call me an old bag for saying so? It's my own J'accuse! What's more, I'm speaking from my own experience. Because, when I consult Instagram, which is mostly to look at the accounts of museums and modern galleries, I'll see tons of things. There are things which interest me… Yet, as much as I try to retain what intrigues me, at the end of the day I've retained hardly anything.

But I would have if I could have really gone to that museum or gallery, if I really saw the work… Not least because that would mean my body made the effort to get out into the world and play its proper role.

In fact, what I see on Instagram, it's just information. I'll say, 'Ok, so that exists, it's there or there' and – well, now I know that. But in terms of nourishing myself or my work, it's useless. Because I need to see real, actual pieces of art to feed my work. So it's something I use with frugality.

I see it more as digital colonialism, as an American export that's just engulfing everything.

Oui, oui, oui. But also – It's really such an easy option. It's just too easy to have access to all those images. You can get this impression you're being enriched, enriched by this enormous plethora of images. But in fact I think it's just the opposite. When I see a drawing on a screen, I feel nothing of its sensuality. I get no sense of those tiny accidents that helped create it, all those things that happened, that contributed to its elaboration. So it's hard for me to really feel or remember anything. It destroys the physical sensuality of the work and nothing could be more important.

Something which should never have been more than a tool has – unhappily – become grafted onto us. There's something that always makes me laugh in the street… It's when you're walking behind someone and – even from far away – you can tell he's consulting an iPhone. Because he's in that bubble, he has a certain way of walking and a totally different gait. He's very concentrated so he pays no attention to anything around him. His body simply staggers, like it has no idea where it's situated in space. It's incredible how a body can become so numbed, so clumsy, so unable to properly function – people even lose the reflex that someone is trying to get around them…It's troubling people can lose themselves in something that's not even part of the physical world around them.

On a brighter note, how do you see "2020 Year of the Comic"?

Without any screens! Ha! Of course, that's not possible… But I actually have a lot of hopes for that! I don't think a 'Year of the Comic' can remain just a year of celebration, just set of festivities that canonize what we do… or pay tribute to how far BD have come. Of course we're going to celebrate the form because it's astonishing; it's something magnificent and joyous and multiform. But I'm hoping it will focus most on the stature of actual artists. Because, in so many cases, that is getting more and more precarious. Statistically, 20% to 30% of BD artisans suffer a substantial lack of security. Among those, women are often most affected.

There's a whole editorial system that needs revision. It's a complicated task, one that is very laborious. Also it's been a long time in the making. But why not at least begin to address it? For example, the whole question of artists' rights…Because in France, BD as a sector does enormously well. As a field, it's flourishing. The paradox is that, for their contributions to it, so many authors and artisans see very little.

Can we not make this huge machine a bit more reasonable? Make it a little more equitable and, thus, more exciting? Of course that's far from a sure-fire idea. Because there are many titles that, while they're not necessarily so interesting, still sell thousands and even millions – and it's partly them that keeps the whole machine in motion. But the problem is their weight tends to crush the small auteurs… authors and artists who may be much more interesting but who suffer from a total lack of attention.

Although, again, I hope it's not just a year of celebrations, there are some great components already in place. I'm not free to talk much about it yet, but things like the exhibitions that are planned – they're wonderful. Plus, the Culture Minister is really committed to comics at the heart of schools and teaching. Comics as a tool that leads towards reading and the arts. It's a long way from that cliché of comics as an idiom for kids and the backward.

I want BD to lead a younger audience into the arms of culture, lead them right into film, history, theatre, literature… I also don't see comics as just a middle-class medium. They can permit any reader to widen their boundaries. It's just something that can bring us closer to each another. BD slip into our daily lives and give real gifts – they spark a new and important set of desires.

- Follow 2020 Année de la BD/Year of the Comic at the French government's official website. At the 2020 Festival d'Angoulême, from January 30 until 2 February, the exhibition Catherine Meurisse, chemin de traverse celebrates the artist's fifteen-year career

- For Meurisse, it is a year full of expositions: until January 11, 2020, Delacroix's original boards are on show at Paris' Barbier & Mathon, Paris; until 1 March 2020, originals from La Légèreté are on show at Rome's Villa Medicis; January 2020 sees drawings by Meurisse exhibited in Japan at the Koganemaru Art Museum, Iki Island. Then, in September of 2020, Meurisse will create a personal exposition for the Academie des beaux-arts/Institute de France

- Delacroix (Dargaud) is out now, with a limited deluxe edition by Barbier & Mathon. As "The Great Outdoors", Les Grandes Espaces has just been published in English by Europe Comics. (Please, someone publish a physical English translation of "Delacroix"!)