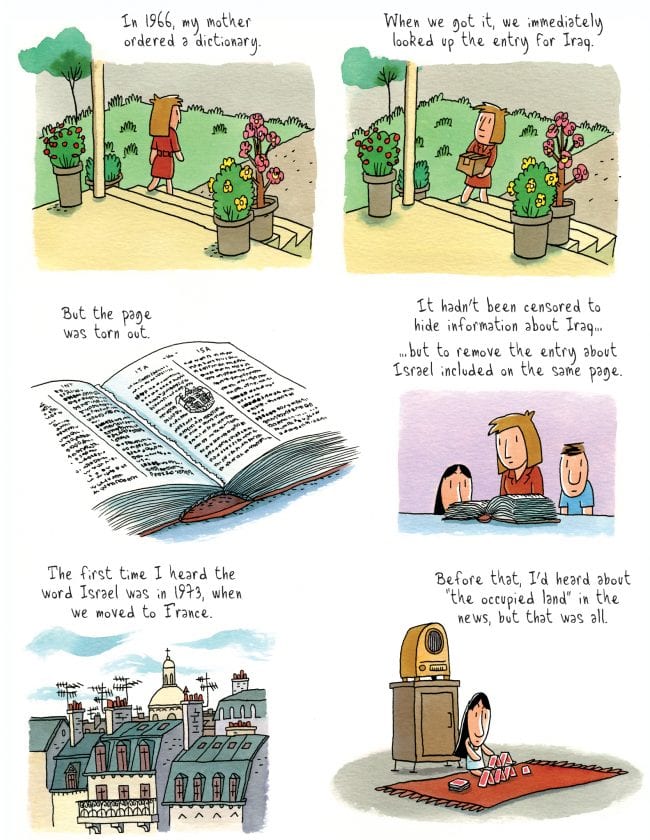

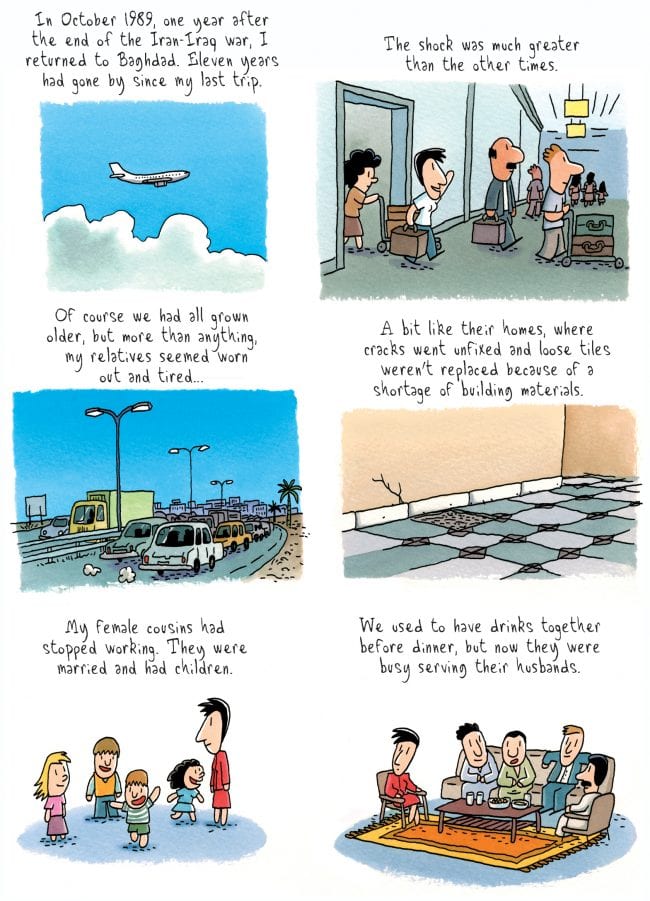

Poppies of Iraq is a deeply personal graphic novel written by Brigitte Findakly and illustrated by her husband Lewis Trondheim. The memoir takes a deep dive into Brigitte’s years spent in her childhood growing up as an Orthodox Christian in Iraq, and traces her life through to when her family moved to France, while showing through Brigitte’s personal lens how the political shifts in her home country of Iraq affected her own family and others.

Along the way, we’re treated to bits of humor, personal reflection, and plenty of poignant moments that give us a glimpse into life in a country that many of us have only heard about in passing, whether it is in news clips, or conversations with other people.

Alex Wong: How did this book come about?

Alex Wong: How did this book come about?

Brigitte Findakly: When all my cousins began to emigrate from Iraq, I realized I would never end up going back. My father was having health problems as his memory was failing him. My mother started to talk a lot more about her childhood. Before, she had always kept that part of her life to herself. Once Daesh entered Mosul -- my birth city -- that was the point of no return for my relationship with Iraq.

It was just at that exact moment that Frédéric Potet of Le Monde, a French newspaper, asked if Lewis Trondheim, my husband, would be interested in creating a weekly comic strip for their new app La Matinale. The project would be to create a strip that was three to four panels long about something from the current news cycle.

At that point, Lewis asked if it would bother me if he tried to put some of my memories in order for that purpose. I had shown him the photo of myself as a child before a door at Nineveh, with the winged lion statue that had been decapitated by ISIS two weeks before. He immediately began from that point, and even used the photograph in his strip.

What was the process behind gathering and choosing key memories and moments from your life for the book?

Brigitte Findakly: I started writing down my own memories of Iraq three years before we started the book. I didn’t know at that point I would end up putting a book together, but I wanted to get down on paper everything that I could recall. So, there were straightforward notes on exactly what happened during my time there.

When I decided it should be an actual book, I started trying to make them accessible for the potential readers, but I just couldn’t find the right narrative frame for these stories. Whatever I wrote ended up being either too simple or too influenced by old feelings.

I wanted to write this story because Iraq had changed so much since I had lived there, and the situation was only getting worse. When I would speak to my family on the phone, they would tell me that I wouldn’t recognize Iraq if I ever went back, and they told me how dramatically their everyday lives had been transformed. I wanted to write this book for myself, so I could preserve my memories and their stories.

The exercise of writing these memories down gave me the chance to figure out the most important memories and the defining moments I wanted to talk about. I also figured that, having these memories written down, one day my children would be able to know what happened by reading the book because we never really had the chance to discuss my childhood.

That must have been a challenging process, and I assume there were difficult memories to think back on.

Brigitte Findakly: Everything became much simpler once Lewis chose the photo of me in front of the winged lion statue and I decided that would be the start of the story. It was a thread we pulled on that unravelled the whole story.

The book isn’t 100 percent chronological, but that’s because, given the current landscape of Iraq, it felt like the present and the past resonated with each other. We thought it would be much more pleasant to narrate the book in this way.

After finding the starting point, Lewis would ask for clarification or additional detail about anecdotes in the story. Sometimes, I wouldn’t have an answer for him, so my mother and my brother -- who is six years older than me -- became excellent resources to turn to.

Because of Lewis’s questions, I ended up learning about things that had gone under my radar while I was living them as a little girl. For example, when we were living in Mosul, we were always friends with Christians and Muslims. I figured that was normal, and that the same was true of my family in Baghdad. Whereas the way the capital was set up, my family was only interacting with other Christians. I had no idea about that.

What was the collaborative process like with your husband Lewis, especially for such a personal project like this?

Brigitte Findakly: When I started working on this as a solo project, I quickly realized my writing was too sentimental. My life wasn’t horror or tragedy. What I wanted to tell was the story of one family. I didn’t want to romanticize it, so I didn’t want there to be a bombastic storyline. I also didn’t want to make up conversations, recreate specific situations, or overstate what had happened. It would have been impossible to keep the narrative pragmatic or be efficient in my storytelling without Lewis.

Emptying your guts to tell your life story doesn’t make it a more interesting or moving one, it just makes it messier. Sometimes restraint leaves more room for empathy from the reader. There is emotional content in this book, but we didn’t want to play anything up unnecessarily.

From the first few panels of the book, I was totally sold on the storytelling technique and drawings that Lewis suggested. I would tell him a bunch of stories and he would quickly sort through them and help me decide if they were interesting, and if that story should be told now or later in the book or not at all.

Sometimes I’d tell him something as background to another story and that would end up becoming an anecdote that made it into the book. That’s what happened with the anecdote about men handling the groceries in Iraq. We’ve worked side by side for 25 years, not always on the same projects, but we know each other very well. Lewis put himself at my service and really listened to what I was saying.

I’m the sort of person who asks a lot of questions before starting a project, whereas Lewis just goes for it once he’s found an entry point. But since we needed to have a strip every week, I didn’t have the chance to prevaricate over them and I think it worked out much better that way. The regularity of the strips meant we had to keep moving forward to avoid falling behind on the project.

What reassured me about working with Lewis is that he wouldn’t hesitate to remove stories I would suggest. Things that seemed important or touching to me, sometimes he’d find them boring or extraneous to the narrative. If I had been working with anyone else, I’m sure they would have just gone along with whatever I asked of them. But since I had confidence in his ability to tell a story in comic form, we could make decisions together on what needed to stay and what could be cut.

Lewis, what were your thoughts about the collaborative aspect of the project?

Lewis Trondheim: The main risk wasn’t that we would mess up the book, but that we would split up over it! Which, thankfully didn’t happen. On my end, another big challenge came from the fact I was drawing 108 pages that were almost exclusively narration. Sometimes I found a solution to avoid that, but often it was difficult to avoid having the text and image being redundant, or to avoid using the same tricks.

But we dug deeper, and would always come up with a solution, and it became a game to keep the storytelling fresh. I ended up using a few sweet visual tricks that wouldn’t normally occur to me, like the parallel between the golden plastic keys of the Iranian fighters and Saddam Hussein’s son-in-law’s Mercedes keys. There was a lot of politically driven violence in the period we’re writing about, so I couldn’t stay with a sweet naive tone, I had to include blood and dead bodies, even if I was lying by omission in my drawing.

In terms of documentation, a Google street view look at Mosul or Baghdad doesn’t exist, but I discovered a website called Panoramio that had a decent selection of street photography that I could reference. Before using them, I would ask Brigitte if these were buildings or homes that could have been there while she lived in Iraq. My experience with sketching was also useful for bringing these to life.

There were also Brigitte’s family photo albums, which helped me get a sense of the interior decor, clothing and cars of the era. People were forbidden from taking photos on the street at the time, and if you took photos of public spaces you could be arrested for spying, which is why there are so few photos available.

Back to you, Brigitte. In the book, you convey very well the overall experience of growing up as an Orthodox Christian in Iraq. How would you describe that experience now that you’ve had a chance to reflect on it?

Brigitte Findakly: I didn’t think about it. I just grew up thinking I was a normal little girl. Life in Mosul was very calm. Our neighbours were our best friends and they were Muslim. When there was a coup d’etat, the only perceptible consequence was that we wouldn’t have to go to school the next day. I never saw hangings, dead bodies or any sort of war scene. That’s one of the reasons I wanted to make this book, to show that Iraq in the 1960s was different from the place we’ve heard about on the news for so many years.

There’s a lot in the book about the history of Iraq juxtaposed against your own experiences living there.

I learned Mesopotamian history in school by heart. For the book, I really wanted to juxtapose my family’s personal history with the larger sweeping headlines from political and historical events. I was hesitant to delve too far into the past. I wanted to stay in my area, beginning in the 1950s. I would have loved to be able to talk about other older facets of history in Iraq. I think Americans would see a different side of the country if they knew that it was the birthplace of beer (Not Budweiser, of course, but just beer in general).

I especially loved the “In Iraq” interludes in the book where we get to learn about traditions and customs of the country.

Brigitte Findakly: Those pages gave us the chance to talk about the culture of Iraq and things that were true to most people who grew up there. It was important to me that this could be seen as a history of many of the millions of Iraqis who exist, and that I wasn’t just telling my story.

There are social customs in Iraq that are specific and different from many other cultures. Specifically, you mentioned in the book about marriages and relationships, that 95 percent of marriages in Iraq are arranged. Did that shape the way you approached relationships at all growing up?

My parents did not have an arranged marriage so I knew I wouldn’t end up in one, even before we left for France. I think my parents were much braver than I was when it came to this. I am and have always been puzzled that my family continues to believe in the practice of arranged marriages. I’ve become pretty fatalistic about this position, though of course everyone is certain their way of being is the right and only way.

Do you have a custom that you miss most?

Brigitte Findakly: The custom I miss most is the polite refusal of second portions of food. I’ve never learned to cope with this sort of polite behavior. Even last month, I was staying with an Iraqi friend in San Diego. I love her with all my heart, but even though I told her several times I didn’t want to play that game, that I didn’t want to have to pretend to not be hungry when I actually wanted seconds, she had a hard time adjusting to it.

Other than that, I think something that always struck me is the closeness in Iraq, where people would just casually drop by other people’s houses to talk. In the West, people are more closed off. Whether it was family members, friends, or just neighbours, you could expect any of them to drop by without notice at your house. There was no expectation that you had to warn someone you were coming. I liked that a lot.

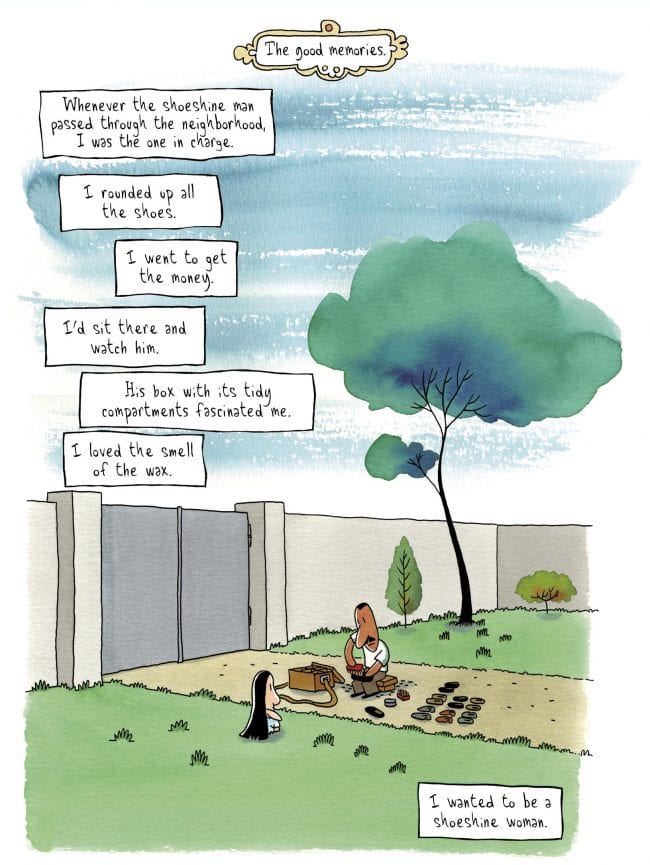

Are there specific things that you miss most about your childhood?

Brigitte Findakly: The same things as most people, I imagine: family get-togethers, my family network, my childhood friends. On the other hand, I don’t miss the harsh discipline that was part of the school system in Iraq at all.

You father, as a doctor, was often very generous and didn’t charge some of the patients he treated. It was such an altruistic approach and I’m curious whether that ever affected your family, from a financial standpoint, or otherwise?

Brigitte Findakly: In certain ways, yes. My mother was worried because she could see that my father was never able to save up and put money aside. But he also spent so much money because he wanted to provide for us. For instance, he sent us to France every summer even though he had to stay in Iraq. He taught me by example, as did my mother. I think that generosity was simply part of the way people were back then.

In your first school assignment in France, you felt challenged because you had to express an actual personal opinion on an essay, something you didn’t do while in Iraq. Were there other adjustments that stood out to you?

Brigitte Findakly: I had to learn the distance and seemingly coldness of people in France wasn’t something I should take personally, but that it just took more time to get to know people there.

There’s an anecdote in the book where you drew the Arab oil for Arabs illustration regarding the oil crisis and it was hung publicly at your school. What was it like to realize, as you say in the book, that if you had stayed in Iraq, you might have become a famous propaganda artist for Saddam Hussein?

Brigitte Findakly: In the book, I definitely mentioned that in a joking way. In reality, if I had stayed in Iraq, I very much hope my parents’ guidance and my education would have protected me from becoming a propaganda artist. It sends a chill up my spine to think of any other outcome.

What is the culture of artistic expression like in Iraq today?

Brigitte Findakly: I’m too far away from Iraqi culture to know exactly what is out there. I understand there are creative movements, but I don’t know of any myself. So don’t expect me to become Iraq’s next minister of culture any time soon [laughs].

You haven’t been back to Iraq since Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait and started the Gulf War. With everything that has happened since, how do you feel about your home country today?

Brigitte Findakly: Pessimistic. Often hopeless. Maybe things will start to turn around, but I can’t see that happening any sooner than 50 years from now, and that’s if things go well. When Iraqi gas is no longer an international issue, the exterior pressures on our country will finally begin to ease off.

Did your parents end up reading the book and what did they think?

Brigitte Findakly: By the end of his life, my father no longer had the ability to read or comprehend what was being read to him, so he passed away without having read the book. As for my mother, she was very happy that the book came out, and she’s read it many times. I think the most exciting thing for her was one morning when she picked up the daily newspaper and saw an article about the book. If that wasn’t enough, the article included the page in the book where she’s making cake for everyone!

Lastly, what do you hope readers get out of Poppies of Iraq?

Brigitte Findakly: I hope they discover a pleasant country with a friendly populace, and that they understand that emigration demands a lot of sacrifices, that people don’t emigrate for the pleasure of a new place. Often the decision to leave is made as a question of survival, survival for oneself, but especially survival and a better life for one’s children.