Ben Sears’ earliest exposure to comics was through newspaper strips. “My experience was just sitting at the table, eating, and the newspaper was there because my dad got it. I was never blown away by the comics, but comics like FoxTrot or something are drawn in a very visually appealing way, even if the story’s kind of inconsequential. You’re just sitting there reading like you would the back of a cereal box. I mean, FoxTrot is definitely drawn better than the back of a cereal box.” Calvin and Hobbes and The Far Side were in the mix as well at that time, and decades later Sears is a cartoonist who makes graphic novels that seem built with the density of comic strip collections. In the four all-ages books he made for Koyama Press, his characters -- the begoggled Plus Man and his hovering robot best friend Hank -- transitioned from treasure hunters pursuing grand adventure into characters whose normal lives slipped easily into the sort of hijinx where they might be, say, pursuing a murder mystery in a house with secret passageways and paintings where the eyeballs move. While I’m far from an expert, they seem like some of the most broadly-appealing all-ages comics out there, due to their sense of humor, and a drawing style that renders their world with a solidity and texture reminiscent of the stop-motion animation of Wallace and Gromit. I can imagine the books keeping a young reader busy for a nice long time, especially if they feel drawn to copy Sears’ characters and backgrounds, whose constructions of linework are so readily apparent and unobstructed.

Ben Sears’ earliest exposure to comics was through newspaper strips. “My experience was just sitting at the table, eating, and the newspaper was there because my dad got it. I was never blown away by the comics, but comics like FoxTrot or something are drawn in a very visually appealing way, even if the story’s kind of inconsequential. You’re just sitting there reading like you would the back of a cereal box. I mean, FoxTrot is definitely drawn better than the back of a cereal box.” Calvin and Hobbes and The Far Side were in the mix as well at that time, and decades later Sears is a cartoonist who makes graphic novels that seem built with the density of comic strip collections. In the four all-ages books he made for Koyama Press, his characters -- the begoggled Plus Man and his hovering robot best friend Hank -- transitioned from treasure hunters pursuing grand adventure into characters whose normal lives slipped easily into the sort of hijinx where they might be, say, pursuing a murder mystery in a house with secret passageways and paintings where the eyeballs move. While I’m far from an expert, they seem like some of the most broadly-appealing all-ages comics out there, due to their sense of humor, and a drawing style that renders their world with a solidity and texture reminiscent of the stop-motion animation of Wallace and Gromit. I can imagine the books keeping a young reader busy for a nice long time, especially if they feel drawn to copy Sears’ characters and backgrounds, whose constructions of linework are so readily apparent and unobstructed.

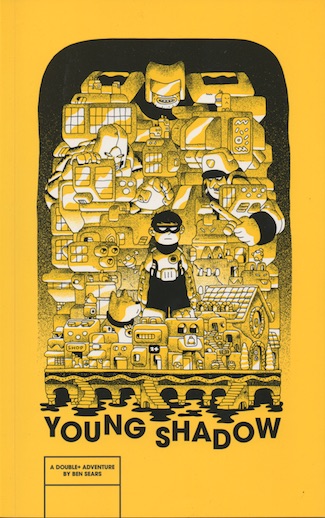

Sears’ new book, Young Shadow, out this month from Fantagraphics, is a slight departure. While the books for Koyama were squat and square-ish, making for a reading experience similar to a more compact version of a European album, this one’s taller, so it has the proportions of a standard monthly comic, and its title character is plainly a superhero. An expansion of a risograph minicomic, forsaking full color for black and white with a nice mustard-y yellow, the reading experience breathes a bit more. There is more emphasis on the page itself as a space where your eye can move around, following Young Shadow as he moves throughout the city. We get two-page spreads. All this action, told in familiar rounded shapes, with gradients of shading similar to the “spray paint” tool in MS Paint, but executed in Clip Studio, takes on this chunky cartoon language that feels related to Frank Miller or Mike McMahon.

Sears attributes at least some of the distinct look of his comics to the influence of superhero art, though he came to that after newspaper strips. “I was looking at some John Romita Jr. X-Men art, and this was early on when I was drawing comics, but after the first Koyama Press book, [so] I hadn’t really figured out a way to render depth very well. So I was looking at this drawing he did and all the shapes had really nice rounded edges, and all the edges were kind of implied by the coloring, there wasn’t a hard black line to say this is the corner of this box, this soft implied edge. So I took that, and since I’m not as good at drawing as he is, it kind of has this wobbly plasticine look to it. And then someone brought up Wallace and Gromit and I was like, well yeah that makes sense, because I watched those a lot as a kid. I’m just filtering John Romita Jr. drawing through the Nick Park lens I guess.”

As for Miller: “I like Batman: Year One and Dark Knight Returns and some of his Daredevil stuff. It’s something I can go back and reread like once a year and just be kind of amazed at how well it all works. It’s an easy read, it’s not making superheroes seem overly serious, like I haven’t read the current Batman but I hear it’s just depressing for the sake of being depressing. It’s just a cool pulpy adventure comic. Stuff like that I definitely reference because it’s appealing to read.”

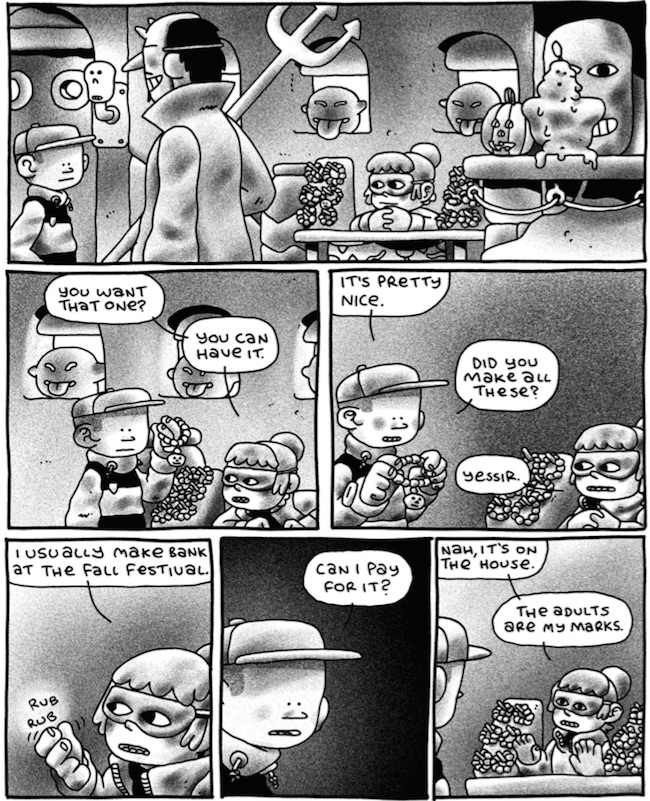

For decades these comics got the opposite rap, cited as a major cause of comics becoming too grim. It’s high time the Frank Miller influence was reclaimed for the side of fun, because those works were readable, while today’s DC Comics are particularly dire and generally not appropriate for, or marketed to, kids. Young Shadow and the Plus Man books have young protagonists somewhere in the age range of eight to twelve. These kids work jobs, drive trucks, and get in fights against armored goons — but the thing that makes them still children, and not just tiny adults, is that in Sears’ comics, and in the real world, children are a separate class with a sense of solidarity between them. They exist in conflict against real estate developers, rich teenagers; this closes the gap between those genre conventions that would feature adults, and ones that feature kids, and makes for adventure stories that are effectively all-ages but nonetheless have a solid and coherent politics to them. Young Shadow gets in fights with corrupt cops, like Batman, but there’s also a running joke added where everyone he talks to hates cops on principle. A group of children not unlike the kid gangs in Jack Kirby comics are analogized to a mutual aid group, an alternative to police that helps people without using guns.

“I had the whole thing finished before I had a publisher so I could do whatever I wanted and not have to worry about, ‘Maybe you should tone down the cop hate.’ Like, you know, I think in this one it’s just gonna be there. Because it’s the state of the world, how could you not hate cops right now? That could get me in trouble, but I think it’s worth talking about, especially in an all-ages comic.”

House of the Black Spot, the last Plus Man book published at Koyama Press, featured real estate development as a major plot point, as motivation for the story’s villains. This isn’t new ground for children’s entertainment; Who Framed Roger Rabbit was released in 1988 and covers it as well.

Ben Sears was born in 1988, and since then he’s been a lifelong resident of Louisville, Kentucky. When protests against police violence were widespread nationwide in 2020 -- with Minneapolis a particular flashpoint for the death of George Floyd -- Louisville was the subject of outrage following the death of Breonna Taylor, shot in her home by plainclothes officers after a no-knock raid. I had read a few people stating that the targeted violence of low-income housing was part of a broader scheme to develop Louisville, and asked Sears about the ongoing gentrification of the city. “People don’t want to live in the suburbs, they want to live closer to the city now. Of course that’s where lower-income people live. So it’s like, we have to get these people out, so we can have single-family homes that are jacked up 400%. I don’t know all the specifics of that because the situation is so evil and stupid and complicated, but yeah, she got murdered because of some eviction scheme for development.”

At the end of May, 2020, Sears designed a graphic suitable for protest signage, and printed t-shirts of it that sold in higher volume than anticipated. Sears was able to sell a thousand “We Can See You” t-shirts in the space of two days, and raised $19,000.00 for bail funds with the proceeds. He and his girlfriend then spent all of June shipping the shirts out. “It was nice to be able to mobilize like that, but it sucks that we have to.”

One of the major ideals behind the anarchist concepts of mutual aid that underlie the movement to defund the police, is that communities of neighbors invested in one another create a strong system, inherently. Beyond the action and gags, one of the things that makes Sears’ comics so likable is how gentle the characters are towards one another. The “we keep us safe” value system isn’t just morally instructive to kids, but is also coherent enough to be reassuring to adults. “Typically you see books like ‘You need to go on this quest and grow into your power.’ Like, no, sometimes things just suck and you have to live in this system that’s not fair, but you can be good to the people in your immediate life and hope that that spreads out a little bit.”

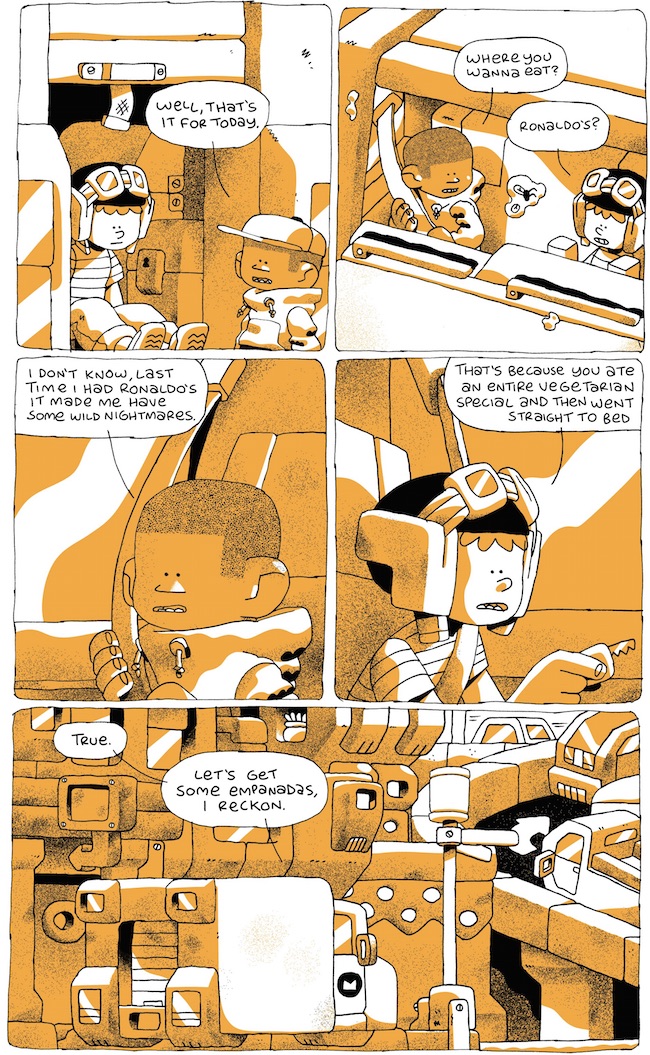

Longstanding superhero serials that apply a “good vs. evil” framework to large casts of characters forever in conflict devolve into brightly colored spectacle. Despite corporate marketing’s best attempts to gussy military propaganda up as modern mythology, all that their self-importance has succeeded in doing is making for a product that’s frequently joyless, and generally too expensive for the lower middle class to access. Sears’ comics remain focused on their characters’ thoughts of what food to eat next.

“Having the people in the comic eat and almost base their activity around what they’re gonna eat later, that’s what people do in real life. It gives people a way to relate to it even if they don’t connect to the fantastical elements of a story. It’s like 'This guy is just trying to get lunch.' In Miyazaki movies, any time they’re eating [something], you can imagine exactly what it’s like to eat that. I’m not drawing it as hyperdetailed visual ASMR as he does, but I feel like cartoon food always looks good.”

What’s next for Sears is a comic called Empanada, which he’s serializing on his Patreon, with new pages up every week. In conversation with me, Sears said, “It’s way different from anything I’ve worked on before, because I’m making it up as I go along, and there’s no end in sight. Usually before I start drawing [a comic] I’ve broken it down into panels and meticulously mapped it out. I try to make them as dense as possible so a lot of things get compressed, and there’s maybe not as much breathing room as I would like to give them. This thing I’m working on now is super-decompressed and just kind of going gently into wherever it’s going to end up.” A recent tweet registered the implications of this new approach: “25 pages in and someone’s finally getting an empanada, eaten off panel unfortunately.”

Something that came up a few times in my conversation with Sears was his belief that his stories flowed naturally from him if he didn’t get hung up on questions of precise detail, like the exact ages of his characters, or world-building. “I like to think of it as being Earth, but not recognizable at all. The backstory is not really fleshed out. It’s one of those things where if I think about it too much it starts becoming about the lore of it, rather than the immediate situation the characters are in, which is more what I’m interested in looking at. It’s something I should probably flesh out a little bit, it would probably help with the big publishers.”

While Sears is comfortable self-publishing his work, to me he seems like an artist any book publisher looking to expand their roster of graphic novels for young readers would want to work with. The characters in the Koyama Press titles have been likable across a series of books, but now that Koyama Press is closed down, their exploits are without a home. “I’ve pitched a couple things and they’ve all been rejected for various reasons. I think because I’m not really willing to dumb things down. Which is unfortunate, because I think kids are pretty smart. They can pick up on a lot of things, more than adults give them credit for.”

I asked if there was a sense, among larger publishers, that his work was too political.

“Not political in the sense of 'Oh we won’t publish something with these views,' but political within 'Kids are not going to understand this.' Which again is one of the frustrating things, because kids hear you listening to the news, all this stuff is happening around them anyway. It might as well be in a book they’re reading as well.”