Alan Grant wrote comics. He wrote lots of comics. He wrote Judge Dredd; Anderson, Psi Division; Batman; Lobo; Outcasts; Robo-Hunter; Blackhawk (the British one from the '70s); Tharg's Future Shocks; Doomlord; Mazeworld; The Bogie Man; Doctor Who; and many more. He wrote comics for American and British publications. He wrote them solo or (often) with longtime creative partner John Wagner. He wrote science fiction, fantasy, comedy, mystery, superheroes, historical drama and even a bit of romance. He wrote stories that were bad, stories that were good, and stories that were great. He wrote 'em straightforward and esoteric. He wrote so many stories that the people in charge had to demand he write under several assumed names so the readers wouldn’t know so many of their favorite works came from him. When he died, aged 73, he left behind a towering legacy as a comics writer.

“Rather than being a successful writer, I’m a failed artist.” That’s how Grant described himself in a 2008 recollection with David Bishop for the Judge Dredd Megazine (#266-268). “I became a writer by default, because I couldn’t draw.” Perhaps this explains how perfectly fitted he was to the medium of comics. It’s not that he couldn’t write other things–he had some scripting credits in television and movies–but his work only ever felt fully expressive when combining words and pictures. Alan Grant was made for comics, and comics was made for Alan Grant.

Born in 1949 in Bristol, but moving early on to Scotland with his family, Grant was seemingly unhappy with any other career but writing. Various failed endeavors in banking and accounting led him to answer an ad placed by Dundee-based publisher DC Thomson. Beginning as a sub-editor in the mid 1960s while still a teenager, Grant quickly found himself fulfilling whatever task the editor above him needed, including horoscope writing... not that he ever believed in that stuff. “I used to try to feel what people would like me to say,” Grant told interviewer Frank Plowright in The Comics Journal #122 (June 1988), "but by the time I’d been at DC Thomson for six months I was writing stuff calculated to keep people in their homes—like 'Do not go outside today, this is an exceptionally unlucky day for you. A relative has probably died, and if not will die soon.'” He would edit and rewrite novels for serialization, compose stories based on torn-out pictures from American publications, and dabble in short romantic prose. While not necessarily the best of times, creatively speaking, Grant would credit that period with teaching him the craft of writing. “It’s a brilliant way of making you discover your own imagination,” he remarked to Bishop, "I came to really enjoy these exercises [the editor] was giving us.”

The journey of discovery came to end in 1968, when Grant discovered LSD and was promptly busted for possession; apparently no one in the city of Dundee had ever been arrested for that particular drug before, so he was sentenced to three months in prison (with one off for good behavior). That experience seems to have really changed the young writer, whose future work would become extremely justice-minded and suspicious of all authority figures (especially those with the power to lock people up). He moved to London in the 1970s, seeking work with rival publisher IPC, which put him to work on encyclopedias, photo-comic magazines and the popular teen monthly Honey. After a short period as a writer and sub-editor on the abortive weekly comic Starlord, Grant (along with much of Starlord's content) was folded into the red-hot science fiction sensation of British comics: 2000 AD, for which his first published work appeared in early 1979.

After a stint editing at the magazine–indeed, after having quit the magazine following a fight over the budgeting of a Judge Dredd Annual–Grant hit the big time when longtime pal and Dredd co-creator John Wagner, whom he had met at DC Thomson, fell ill and needed help with all the stories he had to write. Starting with the long-running “The Judge Child” storyline in 1980, the two would form one of the most fruitful writing partnerships in comics, with hundreds of scripts to their collective name. Aside from Judge Dredd, already the brightest (commercial) star in 2000 AD, the two also collaborated on Anderson, Psi Division (a spin-off), Strontium Dog (brought along from Starlord), Ace Trucking Co. and Robo-Hunter. So prolific was their partnership they had to become inventive with aliases: “I think there are several times when we ended up writing all the stories in 2000 AD between us… so we started the nom de plumes. At last count we had about 14.”1 The pair’s joint work is responsible for what would many would term ‘the golden age’ of 2000 AD, including the ever-popular Judge Dredd storyline “The Apocalypse War” (1982), and the Strontium Dog classics “Portrait of a Mutant” (1981) and “Rage” (1986) - the latter two credited only to Grant, but actually the result of the Grant/Wagner partnership.

All of this was accomplished despite the pair’s obvious discrepancy in style and themes. Artist Arthur Ranson, who worked with both of them, once described their different approaches: “John is [a] very down to Earth, no nonsense kind of writer, it seems to me. Stuff happens and it’s so real and concrete... Alan, his head's all over the place, in far-away places.”2 One can certainly see in Wagner the more cynical type, who took on the brutal world of Judge Dredd as is, able to shift between Dredd as hero and Dredd as villain at ease. Grant was seemingly more emotional, fretting about the possible influences of writing such a fascistic character: “When we started working together it used to worry me an awful lot. We used to have severe lengthy arguments about whether what we were writing was the correct thing to present to kids for reading material.”3

Grant’s presence is especially felt in the seminal “Letter from a Democrat”, which saw Dredd ruthlessly gun down a group of activists, including a mother of two. The woman directly refers to Dredd as Hitler, leaving little doubt what the story thinks of 2000 AD’s bread and butter. You can sense the same in some of Grant’s solo Judge Dredd stories, such as “John Cassavetes is Dead”, a melancholy tale of the past being censored and destroyed. There is little humor to ease the mood, as if the writer cannot forget (and does not want the readers to forget) that Dredd's is an oppressive system; that the protagonist is a monster.

Eventually, the creative gulf grew too large. The Grant/Wagner partnership officially split at the end of the 1987-88 Judge Dredd story “Oz”,4 with Grant wanting Dredd to cement his bad-guy credentials by shooting the heroic sky surfer Chopper in the back, while Wagner wanted to keep the character alive for future stories. Unable to reach an agreement, Wagner took sole control over Judge Dredd while Grant became lead writer on the spin-off Anderson, Psi Division.5

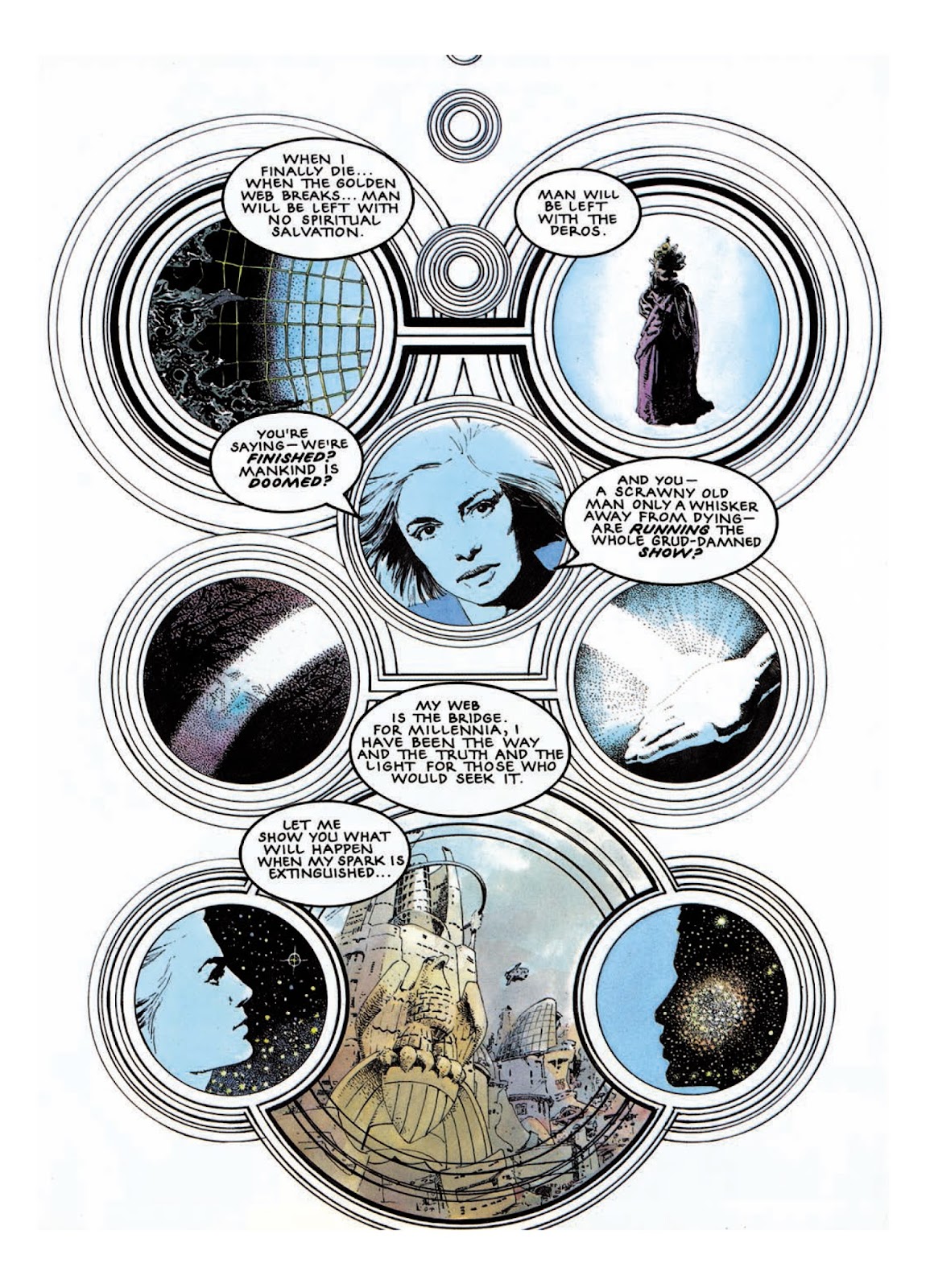

The Judge Anderson stories, focusing on a psychic Judge with a softer approach than Dredd and an affinity to the supernatural (or at least the Fortean), truly unleashed Alan Grant on the world. Where the Judge Dredd stories were often as straight as they come, Anderson proved a looser strip, focused less on action and more on the psychology and philosophy of the character (and her writer). It was both a boon and a curse. The strip could often get lost in its own fancy; the long serial “Postcards from the Edge” (1994), which droned on for ages with little satisfaction, demonstrates how Grant's approach to solo writing could fail him. However, at its height, Anderson truly was as close as the comics form (at least on the commercial genre end) could touch the sublime.

His Anderson stories with Arthur Ranson, such as “Shamballa” (1990) and “Satan” (1995) were a beautiful meld of words and pictures. These truly felt like comics from another world, seeking to elucidate big ideas and big feelings through the medium of action/SF thrills. Moving from the directly political into the metaphysical/philosophical ends of the spectrum, these stories sought to explore the human relationship to both the divine and the vile. Ranson drawing Anderson making contact with the world-mind at the zenith of “Shamballa” is something to behold, and it works not just because the drawings are lovely, but also because Grant dares to trust that the reader will follow him into the stratosphere. The same team would create the equally bold creator-owned fantasy series Mazeworld, which ran in 2000 AD until 1999, showing there’s still room for old hands to experiment and grow their style.

Grant would continue to write for 2000 AD and its sister publication, Judge Dredd Megazine, for the rest of his career; his final 2000 AD credit is a Judge Anderson story, in #2150 (Sept. 25, 2019). However, before the Grant/Wagner partnership split, they made a rather important overseas trip that would define the rest of Grant's career. As with many of his British peers, the late 1980s brought an opportunity to work in the American market. At DC, Grant & Wagner scripted the sadly uncollected-to-this-day Outcasts (1987-88) with penciller Cam Kennedy,6 while Marvel’s creator-owned imprint Epic published The Last American (1990-91), a poetic collaboration with artist Mick McMahon.7

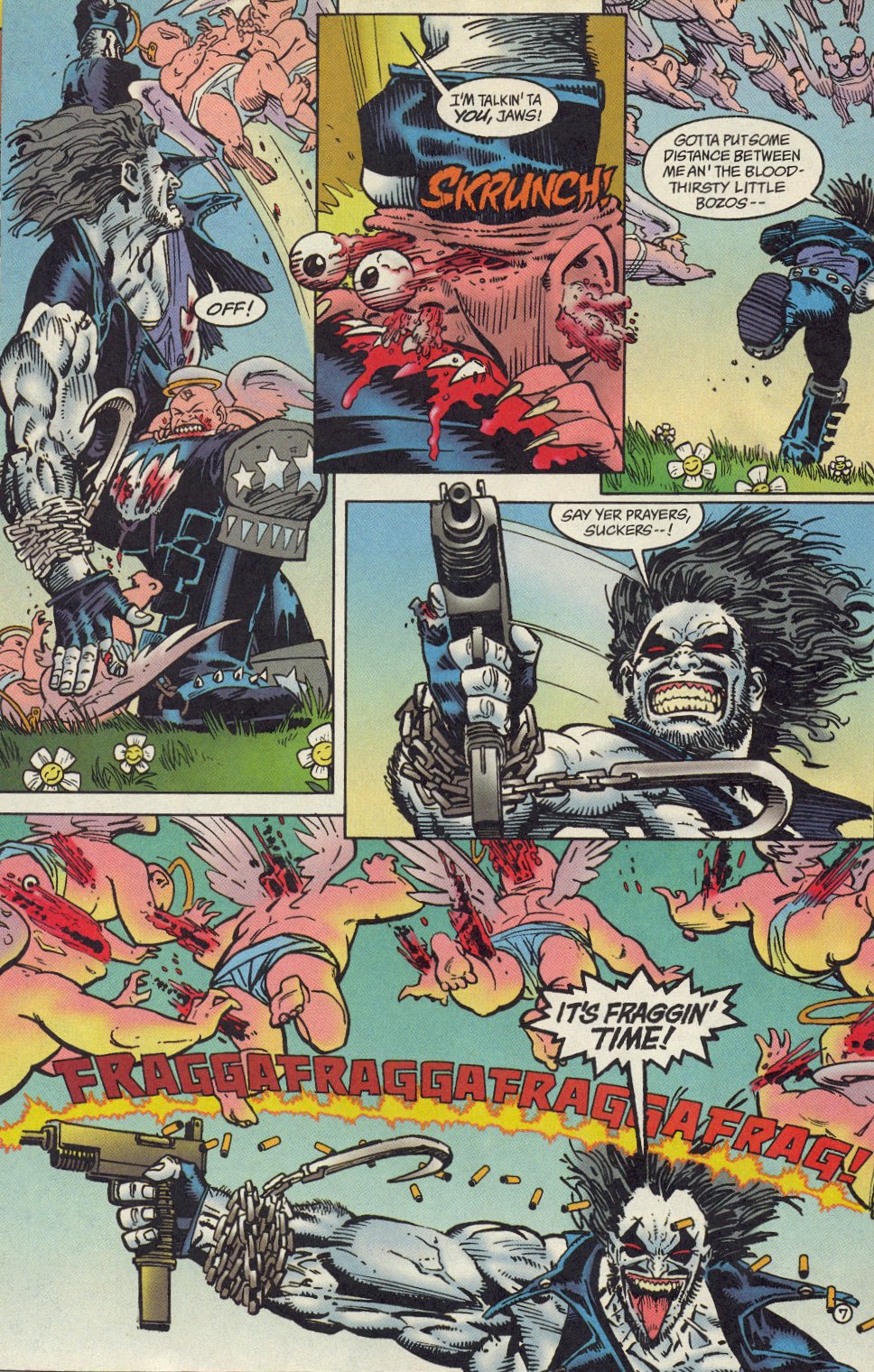

Although neither of these projects were particularly successful in the financial sense, they did help to introduce the pair to an American audience. And after the duo had split, Grant would find enormous, almost inexplicable success on two very different American comic book characters. The first was Lobo, beginning with an eponymous 1990-91 miniseries scripted by Grant from a plot by Keith Giffen, who had created the rude and crude alien bounty hunter with Roger Slifer in the early '80s. Grant would go on to write many dozens of comics starring the character, most popularly drawn by another 2000 AD expat, Simon Bisley.

Grant's work on Lobo was as far away from sensitive Judge Anderson as possible. It was violent, exaggerated, ridiculous, stupid, offensive - everything louder than everything else. Lobo tries to kill Santa Claus. Lobo murders his own children. Lobo is sent to a comics convention. It was as perfect a series as a typical 13-year old could hope for, seemingly made entirely of id, with no room for self-reflection.

But while Lobo was fun for what it was, Grant's 1990s stardom in the American market came from another significant character: Batman. Starting on Detective Comics #583 (Feb. 1988, in collaboration with Wagner), Grant would go on to write many Batman stories throughout the decade, working on every major title: Batman; Detective Comics; Legends of the Dark Knight; and especially Shadow of the Bat, which he wrote for over seven years.

Grant had the good fortune of coming on just as Tim Burton’s Batman film launched a second wave of Bat-mania, but re-reading his comics (mostly through the Dark Knight Detective trade series, which collects his and other issues of Detective Comics) proves they've stood the test of time. Usually drawn by Norm Breyfogle, these, to me, are the definitive Batman stories. While one may point to singular works which transcend what Grant and Breyfogle did, on the whole that run remains unmatched. But you can pick up any random Batman comic written by Alan Grant and it is more than likely that you'll have a winner, and a winner that often wraps up in a single issue. Check out Shadow of the Bat #10, which manages to balance out a thriller plot involving hostages, some possible death traps and a giant enemy mook with a personal tale about dealing with loss and overcoming grief.

Throughout his work on the various Batman titles, Grant would co-create characters such as the Ventriloquist, Ratcatcher, Victor Zsaz and Anarky, which would go on to become recurring figures in Batman stories in various forms of media. Anarky, in particular, was formed for as a vehicle for Grant to explore his developing political philosophy, often in a rather rambling manner (albeit befitting a teenage character). Obviously Grant thought first in terms of a writing an exciting story for his audience, but he never stopped trying to make these stories personal reflections of what he believed. It didn’t always work–attempts at giving Anarky a solo series disappointed seemingly everyone, including the creators–but he never stopped trying, never became just another cog in the machine.

All of that and I’ve seemingly only scratched the surface. Hardly any room left for the surrealistic Tattered Banners (DC/Vertigo, 1998-99), his revival of Kirby’s The Demon in 1990, his stint on IPC's relaunched action magazine Eagle in the 1980s, his late '00s run of classic novel adaptations with Cam Kennedy… there’s too much to his life’s work than can be summed up in a single article. Hardly even room to discuss how he helped many future creators to find a place in the industry, including the time he received a story submission from a young Alan Moore… he asked Moore to make it less wordy.

Alan Grant wrote comics. He did it for more than four decades. He is as much the lifeblood of this medium as the many characters and stories he created. He will be missed. He will not be forgotten.

* * *

- The Comics Journal #122.

- 2000 AD Thrill-Cast, “Arthur Ranson, Part Two”. In the same episode, interviewer Michael Molcher states that Ranson once described the pair as “mythic” and “non-mythic” in style.

- The Comics Journal #122.

- David Bishop, Thrill-Power Overload, page 124.

- Note, however, that the pair would still collaborate occasionally in the following years, such as the indie SF/sports series Rok of the Reds in the 2010s.

- As Chloe Maveal of NeoText notes: a pretty obvious attempt to import the ‘mood’ of 2000 AD as a whole into an American monthly format.

- Thankfully reprinted by 2000 AD's current publisher, Rebellion, in 2017. Some of the best work by everyone involved in it. All the usual elements of post-apocalyptic fiction turned inwards; a mournful lament.