(Continued from Part One)

INFLUENCES

Blood of the Virgin feels like a very unusual comic in some ways, but it's hard to pinpoint exactly how. Maybe it's partly the way you use a lot of classic comics symbols and body language and apply them to a serious realistic story.

Dave McKean wasn't available to draw it for me.

The Hernandez brothers do something similar, especially Jaime, and I'm sure there are others I'm not thinking of...

Chester Brown.

Oh yeah, of course he does that.

I was reading Mary Wept Over the Feet of Jesus, and I was struck all over again by his drawing. He has this cartoon style that's like Frank King silhouettes, very nice, billowy, simple silhouettes, and then he goes in with that didactic shading. There's are a couple people whose work is cartoony but grounded, but also the stories have very complex characters and relationships. Those are people I look up to and aspire to.

Mostly though, it is still looking at old comics. There's two big oversized Tintin volumes that came out when the movie came out. I've never really read Tintin, I can't really read it, but at that size I can really look at it. That, looking at Gasoline Alley, and looking at Roy Crane. I don't hold the books open to study when I work, but it stays with me, it's a guiding principle. To this day, that is still the biggest inspiration. If I look at a Frank King Sunday page, I am floored by the tone of it, the language of the lines. You can't put it into words with great comics like that. There's something that's undefinable, but in my mind, and I think other people feel this, it feels humble, it feels modest. The lines are very thin and uniform, so it feels almost casual and considered all at once. He’s putting all this detail and care into how someone's coat will flap open when they're walking and it's just right.

It makes you really think of those details about lived experience. I think Chris Ware is really interested in that, and he's really good at that. He'll play with scale to make you realize how really weird something is. Frank King is doing the same thing by just drawing a fence being smashed and having each fencepost spread a certain way. It's very deeply felt. These characters, the emotion of it is so strong, you just think, god, he has mastered this and it's 1919. There are pages in Gasoline Alley where he's drawing water and the way he's mastered the spray of water ... That's something artists today haven't figured out, how to draw water [laughs] spraying outwards or how to draw a beach. It's so hard, and he figured it out a hundred years ago and so if I could just harness that and take some of that energy and bring that into another kind of story, I feel that would be cool. Obviously, of course, there's something very disturbing about being so enamored by something that almost nobody cares about.

How so? Why is that disturbing?

Because who wants that? [Hodler laughs] Besides you, who wants that? How many people know about that stuff? I guess Russ Cochran and people on his mailing list, but they're not going to read Blood of the Virgin. I'm not even as good as Frank King [laughs] so there is no point. and so this is just how deep you can go into this well of thinking, where you go, this is a bad idea! What is this impulse to spend years and years on something like this?

Well, there's the commercial element, but artistically, if it works it works, whether or not people know who Frank King is. If you're able to tap into what he's doing on any level, then people will respond to that when they read it, whether they know Gasoline Alley or not.

Right. Fair enough. Hopefully, you end up with a good comic. In 2014, I started realizing that drawing is not so much about drawing realistically or right, it's just design. It's purely this shape which is conveyed as a hand and this shape which is conveyed as a head. Just make it look nice, so when something is not working in a drawing, it's not because it's not "right," it's just that the design is wrong. The line needs to be thicker or thinner or whatever it is. I started looking at a lot of Gil Kane in that way and it was very inspiring. The guy who drew Hägar the Horrible, I forget his name. Dik—

Dik Browne.

Dik Browne! I got some issues of Nemo in Australia. There was some article in Nemo about early Dik Browne stuff, and I thought it was similar to Gahan Wilson. It kind of opened my eyes a little bit to drawing as form, as shape. All that sort of stuff. When you don't have any distractions, you can just think about drawing, like what is it that you're doing? I'd never really thought about it. You're just intuitively working when you're younger, you're intuitively just trying to figure it out, and you just know when it's right. You don't know whats causing it to be right, but when something's wrong, you don't know what's making it wrong, you just know it's not right. With writing, I started being able to see what was wrong, and i would know how to fix it, and it would just be a matter of finding the solution. I would just need to go for a walk and I'll solve it. Drawing was more difficult. It is only in the last two years that I started realizing what drawing is, and it's become easier.

KRAMERS 9

I should ask about Kramers 9 because I'm taking up so much of your time. Is this the first issue that doesn't include any of your own drawings?

I think so. Yes. I'm not in it at all, which is great.

Does it feel as personal a book to you despite that, or does it feel different?

I don't even think about it. This is the first issue I'm really proud of.

Really?

I had done two issues in a row where the format was decided beforehand, where I had a thematic idea and i wanted stuff to fit within that. With the big book, it's large, things have to work at this size, but what happens is that as you work on it the book evolves inevitably, and you can either roll with that and course correct or you can be stubborn and you end up with a book that isn't what you wanted. Kramers 8 was small, and I wanted a certain kind of tone and certain kinds of stories so that was difficult, too. I like the book. I like them all fine, but with 9 I didn’t set the dimensions from the outset, I didn’t decide if it would be a hardcover or a softcover. I let the work dictate everything. I would tell artists to submit but I don't know the exact size. I wanted it to be a size where I can look at the art as artwork, where you can study it as drawings, but I also want it to be a good reading size. If it's only 90 pages, then 11 by 15 is fine. That's a nice size, because it's thin, but if it ends up being a big book, then you'll have to shrink it down because it would be too heavy to read in bed or on the bathroom toilet. So I basically slowly just started asking people to send me stuff with little info. "I'm not sure about the size but it's going to roughly be somewhere between here and here."

The other thing was I decided I would tell people if I wanted changes to their strip. I learned from previous issues where I thought, "I don't love this thing, but it will be fine when the book comes out. I will forget about my problems with it and it will be fine." But it never is. [Hodler laughs] Five years, ten years go by, you look through the book and go why the fuck is that in there? So I told people to submit, I'm not sure what the format is, and also there's no guarantee of inclusion. I think that's good because i think it puts a bit of a fire in people, it puts a bit of a competitive spirit in people. And it gave me the opportunity to take more chances on asking people. There are artists in Kramers 9 who I maybe wouldn't ask if I was definitely giving them a spot, because I'd only want stuff to be great. With this I could take more chances. And some people were rejected and they would submit again or other people would submit and I'd say I really like it, but the ending doesn't feel like an ending, so that conversation might lead to me thumbnailing something for them, and then them either feeling it or not. With other people, it was just talking to them about the story itself, if they wanted to. Some people like sending you stuff as they're working on it and getting feedback and some people want to send you finished stuff. Regardless I tried to treat it like it was my own work, which I think is a good way of treating stuff when you are an editor. You want to run stuff that you can stand behind like it's your own. I think they know that I respect them, so it was all good.

The other thing was I decided I would tell people if I wanted changes to their strip. I learned from previous issues where I thought, "I don't love this thing, but it will be fine when the book comes out. I will forget about my problems with it and it will be fine." But it never is. [Hodler laughs] Five years, ten years go by, you look through the book and go why the fuck is that in there? So I told people to submit, I'm not sure what the format is, and also there's no guarantee of inclusion. I think that's good because i think it puts a bit of a fire in people, it puts a bit of a competitive spirit in people. And it gave me the opportunity to take more chances on asking people. There are artists in Kramers 9 who I maybe wouldn't ask if I was definitely giving them a spot, because I'd only want stuff to be great. With this I could take more chances. And some people were rejected and they would submit again or other people would submit and I'd say I really like it, but the ending doesn't feel like an ending, so that conversation might lead to me thumbnailing something for them, and then them either feeling it or not. With other people, it was just talking to them about the story itself, if they wanted to. Some people like sending you stuff as they're working on it and getting feedback and some people want to send you finished stuff. Regardless I tried to treat it like it was my own work, which I think is a good way of treating stuff when you are an editor. You want to run stuff that you can stand behind like it's your own. I think they know that I respect them, so it was all good.

Did anyone turn in a story that needed nothing? That was just perfect?

Yes, of course. Kim Deitch. Noel Freibert's one-pagers. There were a bunch of stuff that came in and didn’t need anything from me. Most of my input was small stuff: a story not having a title and sending a list of potential titles to the artist, or suggesting a story that was sent to me in color story run in black and white. In the past I would not even suggest that to an artist. This time I did and it went fine. It was a fun project because I started working on it in 2013, and I made sure to only work on it at home. I had rented a room in an apartment to draw comics and there was no computer there, so I couldn't work on Kramers during the day. I wouldn't even work at it much at all on the weekend when I was at home. I would flip through the layout when stuff arrived and I would email people when an idea struck, but it was more like a nice hobby. Like tending a garden. It kept me really engaged with comics in a nice way while working on Blood of the Virgin. And then when it was due, I took the InDesign doc of the whole book that I had been building piece by piece and I opened up a completely new document and only put my favorites in there first, thinking I’ll add my second favorites after. But with only my favorites included, we were at 290 pages, and I was like, that's it. That's the book.

How many pages were in the other folder?

Maybe another forty? Fifty?

That's a pretty good percentage.

Yeah, and it's not like those stories wouldn't appear elsewhere. What happens is it's not that the material is bad, because like I said I was involved in all of it. I told people upfront if I could include it or not, but what happens is at some point you start getting a sense of what the tone of the book is and that idea of course-correcting was very much a part of this, not having a preconceived notion of what it should be, and from there you start seeing that some stories don't fit. There was one story—I won't say who the artist was but this poor person had sent me a story and I loved it. I told him it would go in Kramers 8. I took it out of Kramers 8 because tonally it didn't fit. Kramers 9 comes around, and I ask if I can use the story. Okay, great, it's still available. Doesn't get included. So maybe it will be in volume 10. Sometimes stories just don't fit. Sometimes you're at the mercy of the book itself.

You said this particular story didn't fit and you probably can't go into specifics about why, but is it something that you can articulate to yourself, or is it all intuitive?

At the end of the day, it's intuitive. Because it's not like there's a theme. It's intuitively going I like this and it fits well next to this thing, if you go in order. They're designed to be read in order. Obviously most people don't read it in order, but you're just going this fits here, this fits here. And then I'm getting into this habit, I don't know whether it's good or bad, but there are older comics that I like that I feel like nobody knows about, that I just want to include because no one seems to knows about it. You know Andrew Jeffrey Wright’s graffiti comic? Did you read that?

I read it in the book. I hadn't read it before this.

Right. I read that comic while on tour with Kramer's 4 in 2003. It was in a little art book zine with Andrew, Barry McGee, Ara Peterson, and Leif Goldberg. It was the only comic included and I loved it. It's been a favorite comic of mine for ten years, and I'm wondering if I can include it in Kramers. I figure I can, because for the majority of people reading it, it's going to be new, but that opens up your mind and possibilities and there's other stuff like that.

That Trevor Alixopulos strip, that's an old comic too, right? I felt like I read that somewhere before.

It ran on his website. Kevin Huizenga sent me a link and said you should read this. I was really taken with it. I didn't mind that it ran online. i just want the book to exist on its own terms. I think nowadays a lot of the stuff you're going to get, cartoonists are going to put in minicomics, they're going to put online. You can't control that too much unless you can offer them a really good page rate. So I have to be flexible when it comes to that and just think of the overall book.

I don't think it matters very much anyway, at least to a reader. So many things don't last online. They disappear.

And there's so much good material out there. Mack White is one of those guys I've been thinking a lot about. He's done such weird great comics. That reminds me of something Tom Devlin said to me many years ago, that if cartoonists don't release something on a regular basis, they kind of get forgotten. Comics readers are kind of fickle that way. Mack White is one of those guys.

Does White still draw or is he retired?

He does. He has a website that's really weird, that doesn't look like it's been redesigned since 1997. There's comics on there that are really really small, hard to read. I would absolutely run one of those comics.

Yeah, I've been to that site. There was a lot of conspiracy theory stuff when I went there.

It's true that he got more interested in prose and then the comics got very bogged down in text, but then I think of all these great stories he did that were just weird and really idiosyncratic. He would do these other comics besides the conspiracy theory stuff. Remember the homunculus comics with the little guy with the huge dick? Those were so funny. And there's other stuff. I was thinking about trying to run an entire issue of Dirty Plotte, from the cover to the back cover, running it with the cover on a cover stock, and with the insides on a regular stock, and just run it in Kramers. Maybe I'm entering into Russ Cochran territory, I don't know, but in my mind, she's one of the best cartoonists ever and that stuff doesn't exist in that form.

Does Drawn & Quarterly not keep those in print? Probably not...

I think they want to do it. I think they probably saw The Complete Eightball and were like, what the fuck? We should do that! Certainly the series is good enough for that kind of treatment.

They did Optic Nerve in that box set.

Yeah, they did that with the minis. I don’t think she has good memories of working in comics. I think the comics world was very different then. And there could be a bunch of things involved in a project like that, having to scan and put together this book. It's a lot of work, and not a lot of pay.

Most cartoonists don't have a sense of people's interest in their work or even what makes their work good. She may not think that's the best way of reading My New York Diary or her dream comics. I'm always blown away by how cartoonists—not Julie—organize their work in collections. everything is so compartmentalized. Like the dream comics are in one section, the autobio is one section, the sketchbook is in one section, it kills me. It's like The Art of Tim Sale by TwoMorrows or something. It's these weird ways of putting together a book that often has none of the enthusiasm or problem-solving of their individual comics.

Sometimes it seems like there not a lot of thought put into it. It's just this is the way it's done. I think that something people respond to in Kramers is that it's clear you're thinking about every aspect of it.

I was talking to a friend of mine about Chris Ware. Chris Ware's work has evolved a lot. His work is constantly changing. and your feelings toward his work can change, and my friend made the point that Ware gets a free pass because literally every single comic that's released by an alternative publisher looks the way it looks because of Chris Ware. When Chris Ware started publishing, it made everyone rethink the spine, the endpapers, the indicia. With that in mind, I think it's crazy for an artist not to think about all that stuff when they're working on a book. Once that door opened, it changed everyone’s perception of the mass produced book. Highwater played into that as well, the comic as an object, and D&Q is also a part of that too, but really it's Chris Ware. every aspect of the product can be an aspect of the art itself. It can further your ideas. I think thats even true of good fiction books. I've been reading these two Stephen Millhauser collections, these short stories, and they're so beautiful just as objects.

Have you ever read Alasdair Gray?

No.

He's this great Scottish writer, and he's also an artist. He does all his own covers and does all kinds of typography and design in the books too.

Is it successful?

He's a cult figure, but he's a major cult figure.

I mean visually, as an artwork? Do the covers look good, or do they look self-published?

He's weird. It's hard for me to say if it is successful or not. I don't exactly like his drawing style but I kind of love the overall vibe at the same time.

Yeah, I know what you mean. Hugh Nissenson's a really good novelist and in one of his books, the main characters is a sculptor. So he taught himself to sculpt. [laughs] He included the sculptures in the book and you're like, i don't know if this is working as sculpture, but it definitely adds something to have it included in the book.

Also, with what you were talking about, if you go back far enough, Harvey Kurtzman was thinking about a lot of that stuff. In The Jungle Book, he was hand-lettering all the indicia...

Yeah. I can do it with an anthology, no problem, but doing it with my own work is trickier. because when you've worked on a project for so long you don't understand how to create a context for it. You don't know how to pigeonhole it as a thing, what the tone of it is. There's a couple people who can do it, but one weird thing that's happened over the last twenty years is that artists feel like they have to be their own designer for their own books, and i think it's led to a lot of terrible-looking books. But the guys who do it well, certainly do it really well.

Are there any books you're willing to call out?

No, are you crazy? [Hodler laughs] All these guys are struggling, they just want to sell books. but all these publishers have designers on staff. use them. Or force your publisher to hire a designer that you like. Grab a book that you like, find out who designed it and hire them! Designers are working artists. They'll work on your book.

I had to ask.

No. Poor guys. Come on. I feel so bad for them.

Let me ask you about a couple stories in the new Kramers. You talked a little bit before about how you put a lot of thought into the sequencing. What made you decide to start with the Weissmann story "Silver Medicine Horse"?

Because I think in many ways it has all the elements of a great story. The pathos of the story is built in to the plot itself, so that nothing needs to be explicitly said. The forward momentum of the story has all these themes and ideas and elements that are very strong. It's also visually dynamic. I like that Weissman is an artist who has been drawing and publishing comics for over twenty years, but it feels almost like seeing him for the first time at that size. It feels new. It's got a little bit of a genre thing running through it. It's fun. I love that story.

Dan suggested one other question for you. I don't really agree with him on this, but I'm curious to see what you'll think. He wanted me to ask you why in this issue there's such an emphasis on black humor, and particularly black humor pieces with punchlines?

Oh, that's funny. I didn't realize that. You start seeing themes arise naturally. Stories start coming in, and you start seeing there's something in the air. There's a weird military vibe throughout the book. it's very violent, but there's a certain irreverence as well. I think the Noel Freibert stuff, when he sent me a handful of those strips, I thought these are kind of like the Greek chorus that you could scatter throughout the book. They're really dark, but they're visually playful, they're verbally playful, they're light on their feet, they're sophisticated. His drawing is very, very rich, and that was kind of a rallying cry in my mind of tone. Because it's not guided. I don't think gave people a theme. Often I'll give people little signifiers. I'll go, "Do something scary." Obviously if you're a good cartoonist, you're not going to do a stupid Creepy comic. By scary, i mean something deeply felt. That's not really a question for me, but for the artists. That's the material they gave me. But you've got to embrace that element once the tone of it is felt. That's going to decide the cover image, that's going to describe the paper stock and the format.

I thought the segues between the stories for the most part worked really well, but one that threw me—and maybe it was intentionally jarring—was the segue between the Julia Gfrörer story, "Four Thieves", which is really dark, and then you go to "A New Cruel World", where the guy commits suicide by jumping off a cliff, and these goofy birds fly out and grab his feet... [laughter]

Probably what I'm bringing to it as an editor is foregrounding the innate irreverence of the form itself. There's a bit of a playfulness and that's just a good example of that idea maybe. Sequencing is also all about what you have to work with. You just go, this here, this here... You want the story to end on a spread, or you want the story end on the left or the right. All these things come into play.

It's a very varied book. There are so many different kinds of stories, and some you might not think at first would work well together.

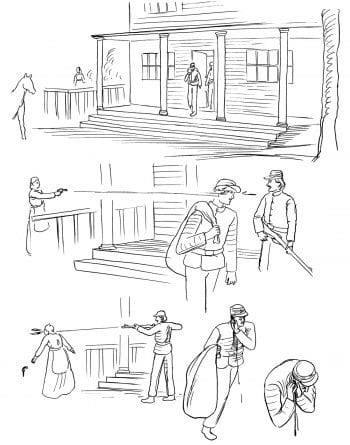

The story that I keep going back to and every time I read it, I read it differently, is the Dash Shaw excerpt.

Yeah! I was going to mention that.

That's an amazing comic. The narration I assume is from a letter that he found, because he's doing all this research for a larger Civil War book. You can read it and reread it and really think about what he's talking about.

Yeah, he's gotten so much better as he's gone on. Lately, he just kind of astounds me every time I read him.

His interests lie all over the place. His interests lie in formal things, but then at the sam time, when he wants to just focus on telling straightforward narrative, he's really, really good at it. I was totally blown away by Cosplay 1 and 2, especially the second one. Issue 2 is such an amazing melding of form and content. I don't read all his work, because he does so many different types of things—I don't know if he's even interested in having readers necessarily follow him everywhere. When he sent that I think the only suggestion I gave him was to add his name, to sign it at the end, so it feels like an ending. [Hodler laughs] It's just so good. His drawing looks great at that size. I don't know if his final book will be that size. It probably won't be, but it scaled well.

Another one I was really impressed by was Gabrielle Bell's.

Beautiful story. That's an excerpt as well. So for the table of contents I suggested giving it a title of some kind. The title that we went with was "Windows". That's the one she wanted to go with, but I gave her all these other suggestions, and all of them were much more on the nose, trying to take something out of the dialogue that I felt if you separate this phrase out of the dialogue and you made it the title, it gives it this rich context to understand the story. She went with the most simple one, "Windows", and I thought, wow, she's got confidence. She's a confident artist, where she can tell a story where the emotional high point of the story is someone talking about light coming in through a window, or the potential opportunity of her daughter being able to drive her pickup around the back, and it's so emotionally felt when her mother says that. To be able to work within that subtle range and to have confidence in that is incredible.

She does so much with so little.

She really does. And she has such faith in the material and the reader. I think that's incredible. It's interesting because, with a story like that I get nervous that it's going to get lost in a book that's loud and goofy, with the layout all over the place and the sequencing all over the place, but at the end of the day, it's strong. Kevin Huizenga colored that story. It's so impressionistic, that color, but it's a nice touch.

There was one story that baffled me to the point where I just didn't understand [Harkham laughs] what happened in it.

Which one?

The Adam Buttrick one.

I don't think we'll be hurting his feelings to say it's initially confusing. When he sent me that story, I thought it might be out order. [Hodler laughs] Is this all of it? I was unsure, but the thing is that you read it once—and i may have hurt it because the green might be a little too dark, if you're not reading it under a bright light, but hopefully it's okay. Anyway, I find that when you read it once, you're like oh what the fuck? Then you go back and it's what we were talking about earlier, about not connecting all the dots for the reader, and being a little bit opaque in a good way, and then you read it again and you start finding these visual connections and you go, okay, I'm following this character, in like your third reading, just this guy. [Hodler laughs] Okay, he's in jail, he comes out of jail, there's this guy selling pencils, he gets to the dock, this thing happens. You go back. You read it again from another character's perspective. There are repeating phrases.

Yes, "Can I kiss your mother?" Variations on that, kissing mothers.

Yeah, what a phrase. and you start thinking about the form itself, which to me reminds me of Mel Lazarus.

Yeah, sure.

I keep thinking of Mel Lazarus. I keep thinking of these very innocent easy forms, and his compositions are very complex. Any single panel is a very interesting complex image. He's doing great stuff compositionally. Like I was saying earlier, I wouldn't have run it if I didn't like it, and the more I read it, the more I felt like it was speaking to me in a very deep way, in a very emotional way. But you know, I think, what's an anthology if there aren't one or two stories that you literally wish weren't in the book and you want to cut out with an Xacto knife? [laughter] That's kind of a given.

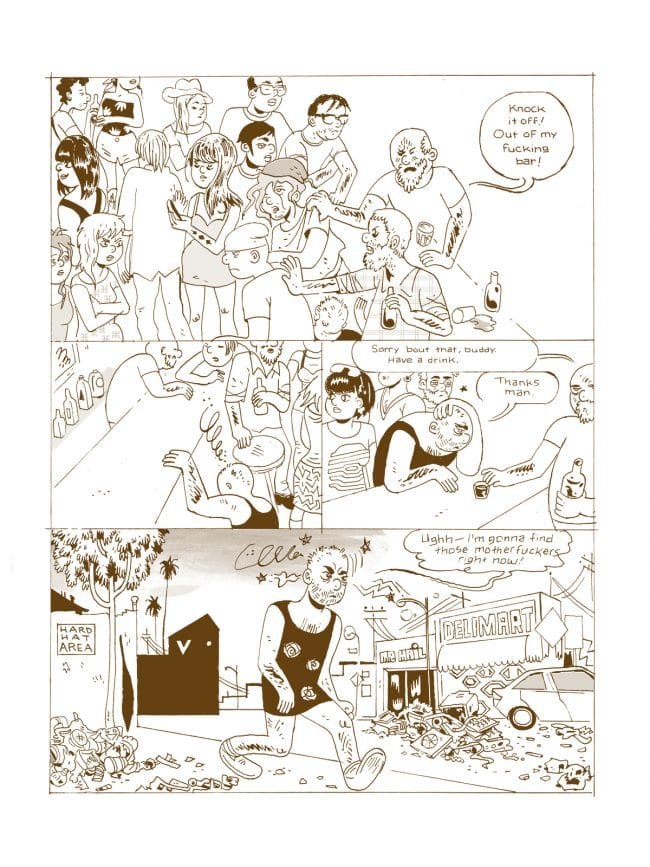

A story that I really liked but that I can easily imagine other people not liking is somewhat similar, "All Our Fucking Dead".

Oh, that's so good, though. I feel like that one gives you all the things you think you want when you go to comic shop and then totally explodes them. They’re talking in these weird cliches. The way it's typeset, it feels like it's very naive. You don't know the context it's created in, if it's ironic, if it's not. You can see it's very smart in how he chooses his buddy-cop-movie cliches, and the drawing is gorgeous, how he he goes all the way with it. I feel like he's turning that whole indie genre stuff inside out. I like it a lot.

Do you have any strategies for finding artists to include, or does it just happen organically?

No, it's just the usual thing, just reading comics and looking around. all the usual things you do in your daily life as a comics fan. The only other thing is driving down the street and getting an fan boy sort of idea, like I would love to see a full-color Tim Hensley sex comic, you know? Can I make that happen? Is that possible?

Can you make that happen?

No, I cannot make that happen. [Hodler laughs] But these are the things that get you thinking. They get your mind going. I've been trying to get Shary Flenniken. The idea of running a Trots and Bonnie section in an issue of Kramers is still an idea that motivates every new issue. but things always fall through.

Have you spoken to her about it? Has it gotten that far?

Yes, she's great. She's really nice. I think she rather wait till she gets an offer for a proper collection, because it's a lot of work getting that material back in print. I read her strip thanks to Dan. He told me about this complete National Lampoon CD-Rom set. I've never bought a CD-Rom in my life, but I bought this set, and I went through every single issue and read every single Trots and Bonnie, and I made a list of all my favorites. [laughs] I got her email from someone, and I got her phone number and we talked a lot. She's really nice, but she's got like a whole other career after cartooning. I think she became a nurse, and then made comics having to do with the health industry. I think her life is just so different that it's ... it's tricky. But you know i think that stuff is so necessary. I think it's great, and it hits that sweet spot for me of that classic cartooning style where it's really weirdly personal inappropriate material. It's so good but I'm still working on it. Debbie Dreschler is another one.

Have you spoken to her? Do you know why she stopped cartooning, or has she stopped?

I think if you read the interview in The Comics Journal you get the sense that she got everything that she wanted out of her system and now she really enjoys nature drawing and doing drawings for illustration for pay. And maybe her relationship with comics was purely exorcising her demons. That stuff is so dark. I think Nowhere is one of the best teenage strips ever. it's right up there with I Never Liked You, it's so good ... and it's rough, man.

Yeah, I couldn't imagine making something like her comics. It would be very hard.

It's heartbreaking stuff. And I think in Nowhere, there's no sexual abuse, but just the way the teenagers treat each other, it's rough. Tough stuff. I don't know how got on this tangent, how did we start talking about this?

I was asking about how you find artists for Kramers.

Oh yeah. A lot of it is getting excited about an idea. That goes all over the place and some of that may not fit. I'd love to get Sergio Aragones to do something. He lived in Spain in a very interesting time. He's been involved in comics for so long in the American market and he's a very gregarious guy, I feel he would be down to do something for a small anthology where he has free rein.

I really loved that you ended on that Tux Dog strip, actually that spread of the Johnny Negron and the Tux Dog. [Harkham laughs] That was a funny way to end an anthology.

Well, you know the funny thing is I kind of put that in the back because after going to shows for years you realize that when people pick up a book on the table and flip through it they go from the back.

Oh.

I realized that will be the first thing people will see. But it's not as aggressive as it would be if it literally was the first thing people would see across from the title page. The Ben Jones comic is so nice because Ben has such a crazy career and he's a good friend of mine so I forget that he even draws. I forget that he's good at that. That comic was in a pile in his office, drawn with a Uniball on shitty paper and it was a goof. He just does it. He's got those natural skills. He's very good at comics. Johnny Ryan's another one. They're just naturally so built for comics, and yet they have no nostalgic affinity. They don't care. If they never drew another comic in their life ever again, they're kind of okay with that. [laughs]

Oh wait, I thought that was the last story, but there's actually a Sof' Boy story right after that. Is that a new Archer Prewitt?

Yeah, it's new. I was putting the finishing touches on the book, and I thought wouldn't it be nice if there was a Sof' Boy comic that ends this book. Because it's such a dark, nutty book, and Sof' Boy is the epitome of that. Every single Sof' Boy story runs that line. I hadn't emailed Archer in many, many years, but I found his email and I asked him, do you want to do a Sof' Boy comic? He said, "Yeah, sure, great!” Wow, that was easy. For some people, that's all it takes. Just ask and they'll do it. Because these guys aren't lifers for comics, but it's fun for them every once in a while. Ben, Johnny, Archer—and he's so good. You look at his skill set and it's just super impressive. He's one of those guys who sends you the file, and it's perfect. You don't need to nudge it. It literally sits on the page perfectly. a lot of the younger artists are the opposite-they send you 200 dpi art, and the line art and the color are in one file. They have no idea how to prep their work for print. I sent Jordan Crane's reproduction guide from 2001 to a bunch of the contributors. Have you ever seen that guide?

No.

This is in the Highwater days, and they were all living in Massachusetts. They released a pdf on Xeroxing written by Ron Regé, how to make a minicomic and steal your copies from Kinko's. Brian Ralph did a chapter on silkscreening, and Jordan did this guide to offset printing. I send that guide to so many people. Because so so many people are just used to printing online.

Archer Prewitt is an interesting artist to me, because he kind of hits the same note all of the time, or a lot of the time, but it always works somehow.

It's just so charming. It's like the Ramones. You know what you're going to get, but it's good.

THE BLOOD OF THE VIRGIN

So let's talk some more about Crickets 5. One thing I noticed in the three installments so far is that the first two each start with one of two different members of the marriage masturbating, and in this issue, near the end, they have sex, though they seem to be mostly asleep, if I'm reading that right.

Yeah, you're reading that right. I hadn't noticed it was a triptych of sexual experience.

It felt very intentionally structured that way to me. Earlier you talked about how you didn't want to story to be cinematic, and I know what you mean, but at the same time when I read the initial two-page spread in this issue, it reminds me of a movie.

One of the things I'm always struggling with is, I don't use narration, and my stories are very much like people in a room talking, so you can end up falling back on cinematic qualities. I don't necessarily think that they're exclusively cinematic. Cinema doesn't have to own them. Then there's cartooning techniques that you can sort of play with subtly that are distinctly cartoony. I don't actively try to make it cinematic, a lot of that to me is more rhythmic.

It reminds me a little of Eric Rohmer. I'm not even talking about their cinematic qualities. Some people don't even consider his movies to be cinematic, because so much of them is just people talking, but in a way, by keeping things that ostensibly simple, he's spotlighting what cinema does at its essence in ways that other people aren’t.

Absolutely. It makes me think of Powr Mastrs and how CF will go from the most elaborate beautiful drawing to a panel of two crude heads in profile talking. It's a beautiful use of the form. That’s always the challenge. If you do a comic where 99% of it is people talking, it's a matter of coming up with visual ways of making that dynamic and play to the form's strengths. So for me, it's pleasurable to watch a character light a cigar off a candle in the center of a table, and watch him smoke the entire thing, and ash it. I figure that's a pleasurable thing to read. Those are the things that are nice in a comic, that you can break down a sequence. I think in Jimmy Corrigan, you have that great sequence of the dad playing with a lid of a can of soda. That’s a really nice sort of move. Just things like that. I remember as a teenager reading Yummy Fur, where there would be whole issues of Chester waking up, putting on the radio, picking his nose and eating it. [laughs] These are the simple pleasures of the form to me.

It also puts an emphasis on things you might not notice—like the character flipping down the mirror above the dashboard—in a way that's kind of subtle and doesn't draw attention to itself.

It's up to you where you put the emphasis. It's a nice thing, because you make everything sort of meaningful in some sort of way, just by the act of drawing someone opening up a mirror in a car, checking their eyes, closing it, opening a window, her hair moving. You're calling attention to all these small minor details that hopefully creates something that feels alive. but hopefully you are not honing in on those sort of emotional details, they are just happening peripherally.

How do you approach composition? Is it intuitive or is there more of a considered method?

It starts for me with the tone of a scene and trying to find the right composition that conveys that tone. I don't think of my art as being very expressive, so if I want something that feels oppressive or sympathetic, it's all about where we're seeing it from, and the number of panels, how large the image is. I have a lot of pages where if you flip the originals over, it's the exact same page penciled a little differently, where it wasn’t feeling right. One that comes to mind is in issue 4, after the whole Palm Springs sequence. Seymour goes to his boss's house and his boss is by the pool. It was such a subtle thing in my mind of wanting Seymour to feel like he's not really welcome in this situation. Where he's slightly not at ease, and it's almost by design of his boss. His boss is trying to put him in the position of insecurity. So besides dialogue and story, you try to do that literally in the framing. I'm not going to do anything dramatic like put a spotlight on him or have like giant letters over his head. I'm not going to do anything formal, because I don't want to get in the way of the storytelling. But it should just read a certain way.

It's funny that you don't think of yourself as an expressive artist, because that's not what I would have said about your work. I mean, this is the most reductive level, but your characters often have very intense facial expressions.

They do, but how they communicate, their body language, all that stuff, I try to suggest things their body language or words are betraying. It’s that Bressonian method of casting. [Robert] Bresson never called his actors actors; he called them models. The idea being that the way someone looks and the way they deliver a line, that's what they are, and you're not trying to bend them into something else. and that becomes the springboard for anything else that character does. I don't know how much this comes through, but there's an element of trying to play with this idea of typecasting, where a certain kind of disposition and manner will imbue everything with a subtext. So even if they're saying stuff thats totally in opposition to how they look or how they honestly feel, it creates a nice sort of tension.

Are there any panels or pages you can think of that do that?

Well, I'm thinking of the scene where they're at the hot dog stand and Seymour's with his wife and then Joy shows up. Bresson never wanted his actors even to emote, just say the line and the emotion of it will create a good tension with the acting style so its not overblown. So with character acting in comics, so much of it is literally if they're saying their lines in their natural way, one of those girls is more happy-go-lucky and easy-going, so even if she's being threatened, you don't have her show that on her face or start clenching her fists... It's basically like life. When I'm lying to you, I'm not making all these grimaces on the side. I'm keeping things completely straight and lying to you. That's how it is. Somebody like Seymour is always frowning, his natural face is always frowning, so even if he's saying to his wife, "I love you, I'm going to miss you," his expression is the same if he tells someone he hates them or that he's upset. To me, that was kind of a breakthrough in how characters work. That's how cinema is useful, because you see how someone like Stanley Kubrick was totally committed to that in regards to character, even if all his characters are over the top in other ways. He liked the James Cagney school of acting. Think of Jack Torrance in The Shining. You can just sort of stay there physically, and emotionally play with it in the content. Does that make sense?

Yeah, totally.

The other big influence on this is Gabrielle Bell.

I was just thinking of her work.

Gabrielle has totally mastered that. She doesn't need her characters to flail their arms around. Blood of the Virgin has a lot of slapstick, and a lot of falling and silly stuff, but usually it's never emotional histrionics, unless it calls for that level of exposed, embarrassing naked emotion. I feel like everyone is always holding their cards close to their chest most of the time.

A couple of days ago—I can't remember who it was but I read an interview with a filmmaker, and they were discussing screenwriting, and he said that one of the ways to build an emotional response in an audience is to have something really devastating happen to a character, but have the character not cry when they should be crying.

Yes. That was written about by Alexander MacKendrick. The cartoonist turned filmmaker. I was reading a good interview with Bertrand Tavernier and he was talking about the first screenwriter he worked with, a screenwriter who worked on all these great classic french films, and he said, if you want to show a lonely person, show him in the middle of a party—and he's the most gregarious person, and counterpoint that with him at home. What happens with comics is that you think to make something emotionally complex it has to be conveyed in the face, but the language of cartooning, it's like two dots for eyes, a mouth, maybe the eyebrows, and certain codified things that we all understand. And when you're younger, you try to break that, because you're trying to do something complex without any understanding of the medium, because really the best thing you can do is keep it simple, and the complexity comes in the accumulation of simple easy-to-read images in relation to each other. I think any great comics show that, if you really study them. It's not any one panel that shows an emotional complexity. This goes back to Kubrick and Bresson; it's very simple, clear, easy-to-read actions but they're placed in an order that fucks with your mind. The complexity comes with the accumulation of the images.

Another thing struck me about The Blood of the Virgin so far, and this may be related to what you said earlier about how you don't plan too much. There are a lot of gaps that the reader has to fill in, about who people are talking about, why things happened, etc. I think that works really well in involving the reader.

I know what you mean. I basically realized while working on the first part of the story that regardless of what I felt the story needed in regards to exposition, I couldn’t draw a scene if I wasn’t invested in it. So I would fold the exposition in to the scenes I was interested in. I don’t want any scene to feel better than any other. Ideally it's all good. I don’t want the reader to think I drew a whole chapter because there was only one scene I really wanted to do. I think it's more fun for the reader because they can sense you're into it and its all working equally well.

I think by leaving things out, it sort of expands the story in a way, too.

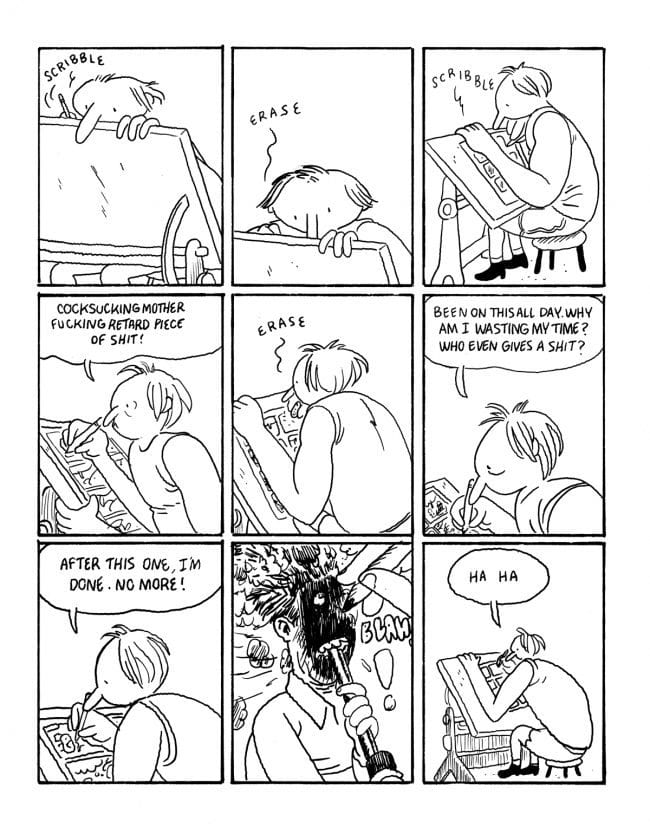

Yeah for sure. It's like that classic Charles Schulz thing. Everyone sees themselves in Charlie Brown. Characters need to be specific enough and they need to be opaque enough. I think from the writer's perspective, they always feel too opaque. It's very gratifying if somebody says "I really felt that" or "I really understood that character, that was a really good detail," because those are the things where you always feel you are being too subtle. The whole nature of doing creative work is that you're doing something that no one has done. There's an element of not knowing if something is going to work, because you've never seen it. [laughs] I don't know if this is going to work. It's a constant thing. It's like fuck—is this readable? Literally, can you read it?

There are moments in the story -- and this might be leading to something later so it's possible this is actually not a good example-- like when Joy has that scar that she doesn't want to talk about it. So much is implied by that, or could be implied by that.

Yeah, thanks. And no, it's not a plot point. I've actually forgotten to draw her scar. I don't know if i've even drawn her wrist again. I've completely forgotten about that.

Well, I reminded you.

Hopefully, you're working on a story and it just comes alive. It starts breathing. I think in the first chapter when she's doing cartwheels and she says, "Go Reds!" or something. I cant remember where she's from, but I knew she was from a certain place, and I looked up all the local high school teams. The characters start becoming very real. Once that happens, it starts informing itself. You're on a roll and the characters just start breathing and hopefully the scar thing doesn't feel fake, it feels real.

Jaime Hernandez does something similar often, too. He'll start a story and even though I'll have read every previous issue, I'll feel like I've missed an issue, because he won't have said how something happened, and there's some new lead character in the middle of some situation.

It's amazing. He's so good. I did a pinup for the Love and Rockets Free Comic Book Day comic, so i was looking at how to draw the characters and really looking at it. This guy, he'll do a scene where it's a bunch of characters in a car just driving together and the dynamics between all these people are so well worked out, it's incredible. That guy just really knows how to tap into it. That stuff you're talking about kept me away from reading his work for so long, because i would try to pick something up and I would go fuck, I don't know what's going on. Eventually you realize that's part of the pleasure. Every time you're going to be dropped in and wonder who's that guy? What's their relationship? And then realize it doesn't really matter. It's nice if you can piece out this person slept with this person, that one is this guy's cousin, but it's not necessary because you kind of get swept up in it.

I don't know if Jaime is trying to replicate this experience, but it's somewhat like if you read Spider-Man #232, and you've never read any other Spider-Mans. There are all these things and past events that are referenced, and they have these little editorial notes that say see issue #131. Just take those boxes out and it makes you feel like there's this whole world that you don't know about. A whole universe.

Yeah, and he doesn't even have to make that joke, because he's now living it. He's now done enough Love and Rockets that you're always going to feel like there's some sort of gap. He's really incredible. I'm so thankful that I didn't read his work so much in my twenties, because now when I read his stories i think this is exactly the sort of thing i want to do. There are so many great stories of his that work as standalone short stories, where there's such a great balance of cartooniness and specific detail. It's very offhand the way he gives information and the way the emotion is felt. He never hits you over the head with anything. I still don't know if anybody ever has made a comic as emotionally satisfying as the end of Love Bunglers. Literally that comic made me tear up, and that had never happened to me before while reading a comic. it was like a new high-it felt like everybody was talking about it.

That is not the first Jaime comic that my wife had read, but it was close to it, and it had that effect on her too.

It's incredible. And then there's other stuff in the issue. There's that great story where all the narration is letters from Maggie's friend and then it ends with her getting into a car crash. It's so deeply felt. It doesn't feel manipulative at all. Thats where years and years of drawing comics can make you so good. It's the equivalent in my mind of like how Schulz doing Peanuts every day, and they're all good and then every once in an while he comes out with such a whopper. You only get there by doing it so much.

Have you ever been tempted to do something like that, where you just keep the same characters going for the rest of your career?

Well, it looks like Blood of the Virgin is never going to fucking end. [laughter] Without realizing it, I am just going to draw this one book. No, usually the thing that excites me about a story is the setting. I get excited about a time and place, like doing a World War I comic or drawing a Western, because it's exciting to learn to draw that stuff and do the research and study it. What's nice in comics is there's all this untaped material in terms of genres, and I say genres not in terms of story structures, because I don't really care about that but just settings. I don't know if I've read a great comic book Western.

I don't know if they're great, but the Blueberry—

I can't even read those. I love Moebius, but for one, his art style is a little bit hacky when he's Jean Girard. Occasionally he'll draw a great panel, but it's so dense and wordy. I want twenty pages of a showdown and a chase. Why can't it be that?

I love the way Jack Davis draws Western comics, but most of those stories aren't really that great.

There's a lot of great stuff to look at visually. There's Tex. Tex is drawn by Joe Kubert or a guy who draws like Kubert, I can't remember. There's a lot of the EC stuff. There's Jack Jackson.

Oh yeah, that's good.

That stuff's really interesting, but I feel like there's space there to explore.

You could always have the characters from Blood of the Virgin pull a Dick Tracy and go to the moon. [Harkham laughs] They could get a time machine and go to the Wild West. There's all kinds of things.

Well, I've had them act in movies that I wanted to draw. I've gotten to put a lot of melting heads in Blood of the Virgin. So that itch always gets scratched. But in Blood of the Virgin so far there aren't many instances of violence, and comics are fun for violence. It's very pleasurable.

Oh yeah, I was going to mention this earlier. A friend of ours came over earlier. She's a poet and she's very literarily sophisticated, but she doesn't know much about comics. And she picked up Kramers 9 and [Harkham laughs] and I was curious about what her reaction would be. She said, "There's a lot of gore and sex in this. I guess more people are interested in this kind of comic than I realized." [Harkham laughs]

That's disheartening on a certain level because the work I am most attracted to are comics that feel like they are using the medium in way distinct to the medium. It's not illustration or animation, it feels like comics. The language of it, the vernacular of the cartooning feels like the medium is being used to get a mainline connection to the inside of a cartoonist’s brain. That's something comics can do better than any medium. That's what attracted me to alternative comics. You get a very intense vision. And those are the best comics. And so while Kramers may be full of work that doesn’t have the veneer of sophistication, I think the work is incredibly sophisticated-they use the medium like masters. If people can’t get past the cartoony vulgar veneer, it's on them, and in fact it's something to embrace, as its something that creates a context connecting new work to the history of the medium. I think Clowes has talked about this, how he's always loved the idea of making a comic that he'd put all his heart and soul into it and he liked that it was embarrassing to read on the bus. I absolutely relate to that idea.

Do you read comics on the bus?

Yeah, always. I always have, but I'm not trying to get laid on the bus. I'm not trying to make friends on the bus.

I know this comic is not really autobiographical, but there's the part where they have movie night and Seymour projects all the movies.

Oh yeah.

For some reason, that seemed to me like something you might have experienced.

Are you insane? [Hodler laughs] Like 8mm twenty-minute versions of Bride of Frankenstein? No! Again, you're trying to know what a scene needs. What’s what is in 1971.

I don't believe you. I still think that's something you do.

[Harkham laughs] The equivalent is me putting on TCM and just not turning it off as much as my wife wants to watch something else-no, we're finishing this terrible Jimmy Durante movie.

At the end of the issue, Seymour goes to a strip club. Is that --

That was real place called the Onyx Club. In the '70s they didn't have what we'd consider today strip clubs. What was cool about the Onyx Club, and I couldn't convey this, because my original pages aren't big enough for these details, but you could see in reference pictures that there's a lot of framed artwork on the walls. All the art is reproductions of famous erotic art. It's like a classy place exotic club. I think I showed one painting behind Carl Barks's head—

[Hodler laughs] Is that Carl Barks? I didn't realize that.

Carl Barks is in the comic. Seymour gets dissed by the stripper because she's hanging out with Carl Barks and Gil Kane.

Whoa! I did not make that connection, but now it's unmistakable.

Are you looking at it right now? Doesn't it look like Carl Barks?

Nice amulet, too.

They're in town for a comic book convention. They had a meeting at Ruby-Spears earlier in the day. Some of the best things for research in the early '70s are French filmmakers making movies in Los Angeles. Just unbelievable, because these guys would come to L.A. to make a movie, and they would get into making everything geographical correct. Like someone gets in a car on Wilshire, they're going to turn right on La Cienaga, they're gonna hit Sunset. There's this really good Roy Scheider movie called Straight Man.

I haven't heard of that.

I couldn't even find a copy of it in English. It's about a French hitman who goes to LA. It's amazing, because of all these real unadorned locations shot in 1971. Beautiful. There's a movie called Model Shop by Jacques Demy, and in this movie the character is driving his car, and I recognized the street. He turns on another street and he pulls up in front of this house and I liked the house. That would make a great house for Val, the boss, because it was in the neo-French retro style, it's a very specific style of Napoleonic and Modern that exists in LA at that time. I thought it was perfect. And I watched the movie and I drove around and I found the house.

Wow.

I followed the directions in the movie and I found the house and I used it for the house in the comic. Luckily so many old movies are made in Los Angeles, and shows like Adam-12 are really good. Columbo is really good. There's all this stuff to pull from. I would say 99% of the time every background in the comic, every setting is a real setting. That makes it more fun to work on. We were talking earlier about the talking heads. One of the ways to make it dynamic, part of that is going like, oh, there's dinner. Well, where? And what is something that will infuse it with history or connect to the theme, something real.

Do you ever do it the other way around, where there's a setting you want to use so much that you think of an excuse to have the story go there?

There's stuff I want to use, and I just have it in the back of my mind, waiting for the right scene for that location. The story takes place in 1971. America was in a very interesting spot in 1971. In many ways I think that our decline as a country started at the end of the '60s. I like that Seymour is trying to make his way in a world that in my mind has already passed. Everything that he wants is already over. Trying to find locations and spaces that can play that up in subtle ways is ideal.

That was the end of the 2016 interview. A few weeks ago, Sammy and I updated our conversation with a brief question-and-answer session via email.

Obviously, a lot of things have changed in the year since we last spoke, not least the political situation. I don't know what your politics are, or even if you're a political person, but I was wondering what it is like to be in the middle of such a long-term artistic project during a time like this. You said you don't want to make any other comics until you've finished Blood of the Virgin. Is it a comfort or a burden or something else to be working on a major project unrelated to the Trump era right now? (Obviously there are a few political signs in the comic: the illustration on the letters page, the upside down flag on the back cover.)

Blood of the Virgin takes place in a very tumultuous time in America, so if I want to talk politics in the strip I have the thematic room to do so. Nixon getting elected after the liberal gains made by Johnson was a huge blow to the left, and reading about that time in America has been useful for the comic and a kind of salve for dealing with today. I hate art that pats its readers on the back, that serves to soothe and confirm their most generic self satisfied opinions about themselves-I genuinely don’t see the point-so while I don’t ignore politics creeping into the work, if they do, my aim is to dig deeper into the issues, making whatever I have to say maybe less topical, but still relevant.

As to my politics, as I get older and get to know more and more successful and rich people, I believe less and less in free market capitalism. I believe less and less in the nobility of humanity-people will demand blood and destruction and strive for power despite their liberal educations or religion, or desire for social justice. everything can be bent to suit whatever feeling is in the air. Since the election, I am trying to focus my attention on the local, the community around me. Fifty states, if you really think about it, is too many for a country. America, since its founding, has always been in a state of violent tension between multiple interests. The last eight years made a lot of people feel like things were turning, evolving to a new normal, which made the Trump victory so much more painful, but I think if we think about america with any honesty, it's always been a well-intentioned, at one point necessary, democratic idea that has never sailed smoothly (and in fact, has likely done more harm than good to the world). Again, reading more and more american history after the election was and is a great way for me to wrap my head around today.

In our previous interview, you mentioned never using narration in your comics. Why not?

I don’t have a stance against narration, it simply hasn’t organically jumped up at me as an element to incorporate.

You have some personal experience with filmmaking ("Hang Loose" is available for viewing online). How, if at all, did those experiences influence Blood of the Virgin?

The short film was made while working on Blood of the Virgin and no matter what regrets I have with the film I can always look at it as, at the very least, useful research for the comic. It gave me insight and help with every single element of the comic strip.

You said you wished there was more room for violence in Blood of the Virgin because comics are so good a medium for depicting it. In this issue, we get a real fight scene, but it's short, quick, and, uh, unspectacular. Any reason for that besides realism?

I should clarify that it is not that I want more violence in the strip-the strip is what it is and I am committed to seeing it through on its own terms. I meant merely that violence plays well in comics, generally. The fight scene in the comic, if it is a fight scene, is what it is for that specific context.

Sex, too, continues to be a joyless affair in this story, as does alcohol and debauchery in general, almost a reversal of the way such things (including violence, of course) are typically depicted in '70s genre films. Are you pushing conservative family values? Ha ha.

I disagree. I think there are numerous instances of people enjoying fucking and drinking and having a good time. Maybe on the periphery, but it's there.

You open this issue with a dream sequence, notoriously tricky material to handle convincingly. Do you have any particular philosophy regarding dreams in art?

Dreams in stories feel incredibly wrong to me until you are literally working on a story and you realize a dream is exactly right. The reason they feel wrong conceptually, just from the stance of armchair pontification, is because a story already works like a dream, both in its emotional structure and the willful ignorance a reader brings when they open a book up. They know the whole thing is a construct, a space to temporarily live in another person’s shoes, so a dream sequence can feel doubly redundant-until it actually makes sense to do it!