Steve Ditko, the comics artist whose vision brought Spider-Man and Doctor Strange to life, passed away at his New York City home on June 29th, 2018. Stan Lee, in his credits for The Amazing Spider-Man, called the artist “Swingin’ Steve Ditko” (issue #10) and later “Scowlin’ Steve Ditko” (issue #27), but if you had to choose one adjective to attach to Ditko’s name, it might be “Uncompromising.”

Consider these facts:

- At a time when Marvel cultivated a house look based on Jack Kirby’s muscular explosiveness, Ditko stuck to his own style — all rubbery sinews and urban shadows. In an extreme version of the famous Marvel Method, Ditko said he told the stories visually, often with little or no input, inventing villains and situations, which Lee retroactively scripted. When communications broke down between the artist and writer, Ditko simply walked away without explanation.

- Ditko’s independent Mr. A comics for Wally Wood’s witzend magazine in the late 1960s expressed his objectivist philosophies in bluntly abstract scenarios, even though they had little appeal for most young comics readers and were out of sync with countercultural ideologies of the time. He continued to draw Mr. A for more than 50 years.

- When Renegade Press publisher Deni Loubert accepted an Inkpot Award on Ditko’s behalf at the 1987 San Diego Comic-Con, Ditko was reportedly outraged and insisted that she return it.

- Plans for a late 1990s comics series to be written and drawn by Ditko and published by Fantagraphics were scuttled after the first issue when Ditko took offense at a coloring mistake on the cover. Offers to make amends by printing the art with the correct coloring in a later issue were rejected by Ditko, who refused to do any further issues.

- In 2007, a BBC documentary, In Search of Steve Ditko, tracked Ditko down to his New York office but could not coax him to appear on camera or be interviewed. Although Spider-Man co-creator Lee made a career of being in the public eye, Ditko gave no interviews after 1968, turning down even a request from his hero, Will Eisner.

- He declined to cooperate with Blake Bell’s 2008 Ditko biography Strange and Stranger: The World of Steve Ditko, calling the book, sight unseen, a “poison sandwich,” and turned the biographer away from his door, as he had many journalists over the years.

- When prominent novelist Jonathan Lethem asked to include a Ditko story in the 2015 volume of The Best American Comics, Ditko turned him down.

- Despite living a Spartan existence eking out a meager living his final years, he refused to sell his original art, which would have been worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. Small-press publisher Greg Theakston told of finding the artist using original Ditko art from 1958 as a cutting board.

To describe Ditko as uncompromising is not to deny his willingness to hire himself out as an artist to just about any publisher who was prepared to sign a paycheck. As a result, whereas Lee worked for one employer his whole life, Ditko turned up all over the comics-industry map, nomadically drifting between comics publishers large and small. But when Ditko inked his own pencils, whether he was working on a co-created character like Doctor Strange as part of the Marvel bullpen or turning in a fill-in, for-hire job like a Get Smart story for Dell or a romance tale for Daring Love, the quality rarely varied. Ditko’s influences can be traced to artists like Mort Meskin and Joe Kubert, but his pacing, his compositions, his expressive faces, his choreographed character movements, his organic environments, even the way clothing draped his figures, were instantly recognizable as uniquely Ditko.

For Ditko, his art was all his public needed to know of him. Just before he stopped giving interviews, he told Mike Howell’s Marvel Main fanzine, “When I do a job, it’s not my personality that I’m offering the readers, but my artwork. It’s not what I’m like that counts [but] what I did and how well it was done.” Even his most personal comics — his Ayn Rand-themed Mr. A stories — were less a conversation with the reader than an expression of his philosophical values through his art. Ditko the Artist and Ditko the Objectivist were always there for examination. But Ditko the Person remained an enigma — a recurring theme in his character designs (see The Question, The Missing Man, the shadow-shrouded Mocker, the faceless Mr. A).

Ditko, the flesh-and-blood person, was born Nov. 2, 1927, in Johnstown, Pennsylvania. His father, Stephen, worked as a master carpenter in a steel mill and his mother, Ann, was a homemaker and seamstress. Young Steve was an only child for his first seven years, but was eventually joined by two brothers and two sisters. In high school, he was a member of the science club and a club devoted to carving model planes to aid in the training of enemy-plane spotters. Upon graduating in 1945, he did a stint in the Army, during which he was stationed in postwar Germany, drawing cartoons for the military newspaper. During this time, he produced a monthly comic book and mailed it to an audience of one: his brother Pat.

After returning to civilian life, Ditko enrolled in New York’s Cartoonists and Illustrators School (today known as the School of Visual Arts), where he studied under Batman artist Jerry Robinson. One of his classmates was future bondage cartoonist and photographer Eric Stanton, with whom Ditko would share a studio from 1958 to 1968.

In 1953, Key Publications hired Ditko to draw a Bruce Hamilton story called “Stretching Things.” It was his first professional comics work, though it was resold by Key to Ajax-Farrell, which published it in Fantastic Fears #5 only after a second story for Key, “Paper Romance!,” had seen print in Daring Love #1 (published by Key imprint Gilmore Publications).

With his foot in the door of the comics industry, he was employed the same year by Jack Kirby and Joe Simon’s studio. There he worked alongside Mort Meskin (Sheena, Johnny Quick) drawing a story for Black Magic and doing backgrounds for Captain 3-D. The 3-D gimmick failed to catch on, and Ditko was let go after only three months.

He immediately found work at Charlton Comics, beginning a relationship that would continue off and on until Charlton finally shut down three decades later. Charlton was a prolific, though notoriously cheap, bottom-of-the-barrel comics publisher, but Ditko was able to crank out pages largely free from editorial direction. In less than a year, Ditko drew 170 pages and 19 covers for Charlton, with a concentration on pre-Comics Code horror comics. He accomplished this in spite of suffering from the onset of tuberculosis, which brought his work to a halt in 1954.

Under the care of his mother, Ditko recovered by the following year, but while he was recuperating, Charlton was knocked out of operation by a hurricane. In 1956, unable to return to Charlton, he signed on at Marvel, then called Atlas Comics, where he drew stories for titles such as Journey into Mystery, Spellbound, and World of Suspense. For the next several years, Ditko would oscillate between Marvel/Atlas and Charlton, the two publishers for which he did the bulk of his most significant work.

When Marvel downsized in 1957, he went back to Charlton, which had recovered from its hurricane damage. But a year later, he accepted Stan Lee’s invitation to draw for Marvel again. This game of musical chairs allowed Ditko to be in on the creation, with Joe Gill, of the long-running Captain Atom character for Charlton (first appearance: 1960) and put him in the right place at the right time when Lee and Marvel publisher Martin Goodman decided to experiment with its Amazing Fantasy anthology title in 1962 by adding a superhero character.

The first 38 issues of The Amazing Spider-Man proved to be Ditko’s most enduring success. Even today, Spider-Man movies and comics are still trying to find their way back to the combination of elements that Ditko instilled in the series: the youthful exhilaration and aerial ballet of Peter Parker giving vent to his web-swinging powers, the down-to-earth subjective point of view of a troubled adolescent, the smoothly paced storytelling. How much of the character can be attributed to Ditko and how much to Lee has been the subject of endless debate. Even Jack Kirby had a claim, having drawn the first cover and an earlier unused Spider-Man character design and partial story at Lee’s direction. But it was undeniably Ditko who established the look and feel of the series as it was published. The Marvel Method gave him considerable leeway to develop characters and storylines, and this was especially true as Lee gradually abandoned his pre-penciling story conferences with Ditko.

When Lee later referred to himself in interviews as Spider-Man’s creator, Ditko objected. In Sean Howe’s Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, Lee recounted a conversation in which Ditko told him, “Having an idea is nothing, because until it becomes a physical thing, it’s just an idea.’” Lee responded by arguing that “the person who has the idea is the person who creates it.” Unless you believe that what made the first Spider-Man comics great was that they were about a kid who gets bitten by a radioactive spider and gains arachnid powers, then Ditko’s point seems valid. We readers didn’t fall in love with a synopsis; we were captivated by the way Lee and Ditko brought the idea to life.

Ditko’s work on Spider-Man with Lee was less a collaboration than a dialectical collision. According to Marvel writer/editor Roy Thomas, Lee and Ditko disagreed on just about everything, from aesthetics to politics. But it was a collision that made possible a uniquely affecting comic book. Lee conceived the teenage, high-school milieu but Ditko protected that world from Lee’s more fanciful, cosmic ideas, arguing that Spidey’s villains should be rooted in the streets of New York. The Amazing Spider-Man combined Ditko’s story pacing, character design and wiry movements with Lee’s self-aware dialogue, Ditko’s interiorized existential dilemmas with Lee’s trademark tension between the ordinary and the extraordinary.

Years later, in 1999, Lee issued an open letter to the press stating: “I have always considered Steve Ditko to be Spider-Man’s co-creator. … I write this to ensure that Steve Ditko receives the credit to which he is most justly entitled.” Ditko, in a 2002 essay printed in his Avenging World collection, dismissed the gesture, drawing a distinction between considering Ditko to be Spider-Man’s co-creator and avowing that Ditko is Spider-Man’s co-creator. On the face of it, Ditko’s position seems to be absurdly contrarian. But maybe Ditko understood that Lee made the statement not so much because he believed Ditko was co-creator, but because, as he said in Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, “Steve definitely felt that he was the co-creator of Spider-Man. … So I said fine, I’ll tell everybody you’re the co-creator.”

When it came to Doctor Strange, however, Lee attributed even the “idea” to Ditko. “’Twas Steve’s idea,” he wrote in a letter to The Comic Reader #16 in 1963. Strikingly different from other Marvel series of the time, the world of Doctor Strange is as far removed as possible from Peter Parker’s high-school life — and it is just as singular a vision. The sheer alien-ness of Ditko’s writhing inter-dimensional pathways, swirling ectoplasm and spells conjured as fizzing, flashing, arcing light shows threatens to disintegrate into unbounded abstraction, but the figure of Strange guides us through it all and Ditko’s sensitivity to the interaction of story and perspective maintains coherence. Strange is as straight-faced a hero as they come, but even in this title, Lee’s goofy necromantic wordplay (the Eye of Agamotto, the Seven Bands of Cyttorak) keep things from becoming too dour. It was easily the trippiest of Marvel’s titles and was affectionately embraced by the mind-exploring counterculture. Strange showed up on an early Pink Floyd album cover and was referenced in Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test as Merry Prankster Ken Kesey’s favored reading material. An early concert series organized by the Jefferson Airplane was called A Tribute to Dr. Strange. Four years before the Beatles had their minds blown by the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in 1968, Dr. Strange found his way to enlightenment and mystical powers after he journeyed to Tibet and studied at the feet of the Ancient One.

Although he was mistakenly identified by some readers as a fellow head, Ditko, ironically, had no use for the hippy movement or any other collective movement. He had by that time come under the influence of Ayn Rand’s writings and her conservative philosophical perspective had begun to creep into his work. For Rand, every individual must fight his or her own battles and should not become involved in collectively conceived actions. The cartoonish depiction of campus protesters in Ditko’s Spider-Man, therefore, presumes them to be motivated entirely by confusion and vanity rather than by political awareness.

The Incredible Hulk, which featured a star who could be seen as the ideal Rand-ian self-motivated, outsider figure made its second debut as one half of Tales to Astonish in 1964. Ditko had taken the series over from Kirby with The Incredible Hulk #6 just before its first run was aborted. Like Doctor Strange and The Human Torch in Strange Tales, the revived Incredible Hulk shared Tales to Astonish with another series (Giant-Man), which meant that Lee and Ditko, who had previously focused on short stories for anthology titles, had to adjust to telling episodic tales that continued from one cliffhanger to another. In that, they succeeded, whipping both Incredible Hulk and Doctor Strange into a compelling soap-opera momentum.

For fans, these were the golden years of Ditko’s career. They lasted until 1966, the year of Spider-Man #38, Ditko’s final Spider-Man issue before he left Marvel. He has steadfastly declined to reveal the reason for his departure, but there are theories galore in the comics community. Some say Ditko’s new objectivist philosophy clashed one too many times with the parameters of the Marvel universe. Certainly, Lee and Ditko had ceased to work together. Ditko constructed his stories visually and Lee interpreted them verbally, with neither creator consulting the other. The conflicts reportedly stemmed from Ditko’s relationship with Goodman, who Ditko felt, owed him merchandising royalties. The problems between Lee and Ditko might be attributable to the fact that each served a different master, Lee obliged to carry out Goodman’s directives and Ditko loyal to Rand and her view of the world.

During Ditko’s time at Marvel, he often provided inking for studio mate Eric Stanton’s bondage-themed, under-the-counter comics (Sweeter Gwen, Confidential TV). Stanton told Eric Kroll (in The Art of Eric Stanton) that he would also occasionally assist on Ditko’s Spider-Man work, but denied having any significant impact on the Marvel character. For his part, Ditko never acknowledged doing any work on Stanton’s comics. When asked about Stanton by Loubert and others, Ditko would shut the conversation down. Why did Ditko, the self-made objectivist, who was so immune to the mores of the masses, balk at owning up to his contributions to a few kinky comics pages? It’s a question that touches on what may be the biggest absence in public accounts of his life. There is no indication that Ditko was ever intimately involved with another human being. No marriages. No romantic flings. (A report by Will Eisner that he had met Ditko’s “son,” was never corroborated and Eisner is generally presumed to have mistaken Ditko’s nephew for a son.) His compulsion to sweep his sexually themed work with Stanton under the rug may suggest a reticence about such matters. Or it may just stem from the severely honor-bound Ditko’s determination to be discreet about his ghost work for another artist. There was, after all, very little that Ditko wasn’t happy to sweep under the rug.

Ditko and Stanton ceased to share working space after Stanton married in 1968. By that time Ditko had left Marvel, returned to Charlton and, thanks to former EC artist Wally Wood, begun doing work for three other publishers: Tower, Warren and Wood’s own witzend zine. At Charlton, in 1966, he reunited with his Captain Atom character and revived, as a Captain Atom back-up feature, Golden Age superhero Blue Beetle, which Charlton had acquired from Fox. Blue Beetle got his own title in 1967 and, as a back-up feature to that comic, Ditko introduced a new character of his own called The Question. The Question was straight out of the Ayn Rand playbook: an individualist with unerring instincts who publically exposed corruption in his daytime identity as a crusading journalist, while anonymously punishing bad guys as a faceless vigilante. The Question made use of the police and was aided by a scientist companion named Aristotle, but essentially, he acted as a lone judge, jury and, sometimes, executioner, imposing his perfect sense of justice on the world. Charlton, however, was beginning a permanent financial decline, and The Question was soon taken out of his creator’s hands, popping up in the 1980s at DC, the new owner of Charlton’s properties. (The revived series was drawn by Denys Cowan and written by Denny O’Neil, who toned down the violent vigilantism and gave the protagonist more of a Buddhist point of view.)

But the purest expression of Ditko’s philosophical views as filtered through the superhero genre was Mr. A, a self-created, self-owned series first appearing in Wood’s witzend #3 in 1967. Unbound by the Comics Code, Mr. A meted out vigilante justice that was even more bluntly unforgiving than that of The Question. Mr. A, like The Question, confronted crime as both a journalist and as a masked champion of justice. In Mr. A’s black-and-white world, there was right and wrong and nothing in between. Wearing an emotionless steel face-plate, the implacable avenger ensured that those who were guilty of ethical compromise would pay for their crimes. Along the way, he delivered ideological monologues on how not to stray from the right path.

As editor of the newly formed Tower Comics, Wood also hired Ditko to draw stories for the line’s shared universe of titles spun off from T.H.U.N.D.E.R. Agents, which combined superheroes and international super-spy organizations. Though remembered fondly by some, Tower failed to catch on with a broad audience and folded within a couple of years. During the same period, through Wood’s connections, Ditko received assignments for Warren’s horror magazines Creepy and Eerie. From “Room with a View!” in Eerie #3, cover-dated May 1966, to “The Sands That Change!” in Creepy #16, cover-dated August 1967, Ditko turned out regular stories for Warren, often working with writer Archie Goodwin. Continuing to expand on his style, Ditko experimented with washes and charcoal effects in these black-and-white works. Goodwin left Warren in 1967, as the company was going through a difficult financial period, and Ditko shifted all his energies to Charlton, which was itself holding on by a thread.

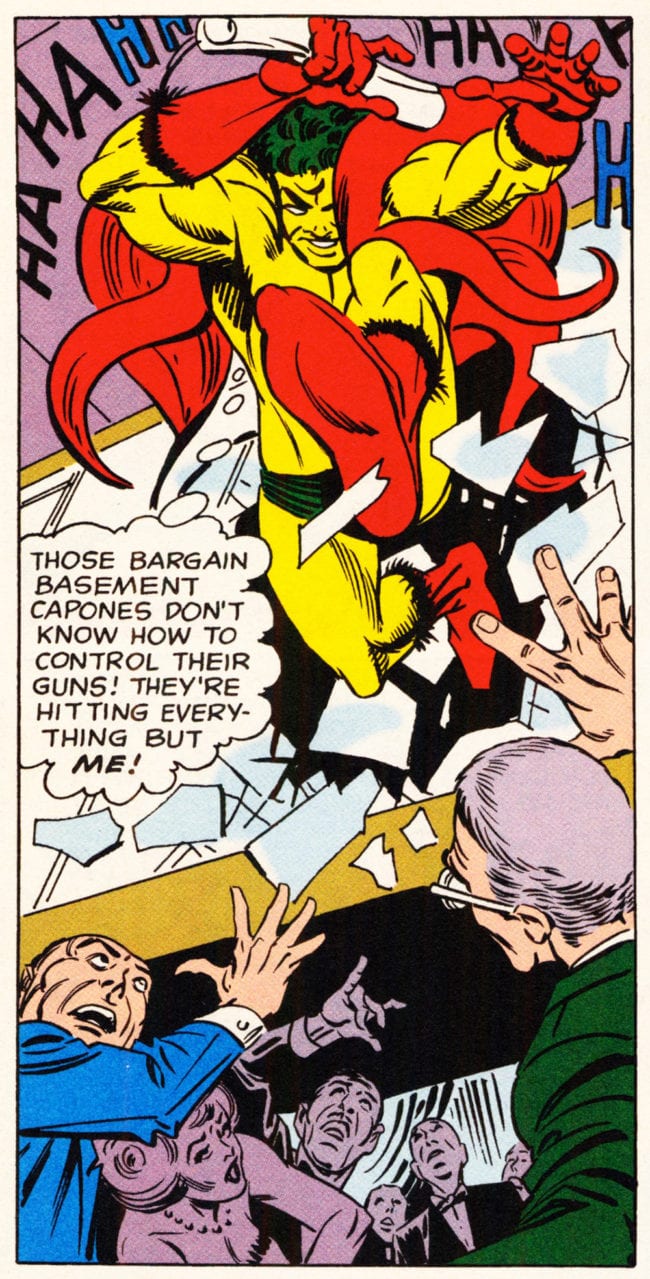

Ditko finally came to the other big superhero publisher in 1968, creating the eccentric Creeper for a DC Showcase tryout. The Showcase run was followed by a series (written by Denny O’Neil) that lasted six issues. As with The Question and Mr. A, The Creeper’s civilian identity was a media figure, but unlike virtually every other Ditko character, The Creeper’s powers also rendered him irrational and psychotically unpredictable. Working with writer Steve Skeates, Ditko’s second 1968 Showcase creation for DC was equally unconventional, introducing a pair of super-heroic brothers known as Hawk and Dove. The series’ clever concept was to have the duo’s teamwork emerge from the dialectics of their opposing psychologies: One brother was a pacifist and the other was bluntly forceful. Because their divergent approaches reflected the nation’s ideological split over the Vietnam war, it was naturally a difficult narrative tightrope to walk, especially given Ditko’s own distinct leanings. Both O’Neil and Skeates clashed philosophically with Ditko’s interpretations. Ditko characters’ allegiance to a belief system that starkly divided the world into good and evil led them to casually cause or allow the deaths of anyone they considered to be on the wrong side of the ethical border. By contrast, when a villain would meet a violent end, O’Neil would insert a degree of empathy and regret into the story. When Skeates would have Dove commit an act of bravery, Ditko would object that such acts went against the conceptual integrity of the character. Nevertheless, the artist tolerated these changes with what O’Neil described as thorough professionalism. When Ditko left Hawk and Dove after only two issues, it was because the tuberculosis he had kicked in 1954 had come back.

Ditko’s health returned, but his career was at a low ebb, surviving on his fallback Charlton assignments as the 1970s began — though his work was continually being rediscovered in reprint. In 1975, Ditko penciled, Wood inked and future DC President Paul Levitz wrote Stalker, a short-lived sword-and-sorcery series for DC. Because he had walked away from his seminal Marvel work and because the other longstanding characters that he was associated with were part of the floundering Charlton line, Ditko was generally given assignments on start-up series, which rarely lasted. His style was so distinct that for him to take over a Batman or Superman series would have been jarring for longtime fans.

Whatever differences Ditko may have had with Martin Goodman and/or Stan Lee, he was willing to work on the Destructor start-up series edited by Lee’s brother Larry Lieber for Atlas/Seaboard, Goodman’s imitation-Marvel line. Ditko created the series with Archie Goodwin in 1975, and Wood again supplied the inking, but the title lasted only four issues, the Atlas line itself expiring within the year.

Working for DC from 1977 to 1979, Ditko created Shade the Changing Man, another start-up, and both wrote and drew an eight-page back-up feature in World’s Finest that revived the Creeper. Though scripted by Michael Fleisher, Shade, an alien hero with a protective vest that distorted his appearance in response to the mental states of those around him, was fundamentally the product of Ditko’s imagination. The artist had long-term plans for the character, plotting the stories 17 issues ahead, and the title found an appreciative audience in the burgeoning comic-shop market among fans looking for something different. Unfortunately, Ditko fell prey to the 1978 DC implosion, in which the publisher ended a period of expansion by canceling most of its recently launched titles, including Shade with issue #8. The Creeper back-up series ended a few months later, at the beginning of 1979.

Ditko made a return to Marvel in 1979 to relaunch Jack Kirby’s Machine Man with writer Marv Wolfman. He continued to work on Marvel titles through the 1980s and, perhaps because of the didacticism that had become entrenched in his characterizations, Marvel editors apparently felt he was best suited to work on mechanized and other nonhuman heroes — a far cry from the high-school-rooted Peter Parker. His assignments after his return to Marvel included toy-based series like Rom the Space Knight, a Transformers coloring book, a couple of fill-in Micronauts stories and the Micronauts spin-off Captain Universe. Ditko had often supplied much of the detail in his art at the inking stage and that was even more true of his later mainstream work. Ditko inked his own work on Machine Man, but after that, he settled into a pattern of providing an economically sketched layout for other inkers to finish. Blake Bell observed that this is similar to a strategy employed by Rand’s Atlas Shrugged character, John Galt, who did work for hire, but reserved his creative energies for his own projects.

Ditko’s creation (with writer Tom DeFalco) of Speedball in 1988 stood out from his other 1980s Marvel work. Though he continued to leave the inking to others, Ditko plotted the series, with scripting mostly done by Roger Stern. The character was introduced in a Spider-Man annual before getting his own title, emerging from a Spider-Man-esque origin that involved another teenager running afoul of another lab mishap. The look of the character, however, was distinct and his powers manifested through the flash and pop of a giddily visible cartoon physics. The series lasted 10 issues, ending in 1989. The character was later revived by other creators and recruited into The New Warriors in 2014.

In addition to his Marvel work and several stories for Archie’s Red Circle superhero line, Ditko tirelessly sought out venues among the many newly launched indy publishers in the 1980s. Identified as part of the old guard of superhero artists, Ditko was given back-up series in Kirby’s Captain Victory and the Galactic Rangers and Silver Star for Pacific Comics. Ditko intended The Mocker, about a vigilante who terrorized criminals with his power over darkness, as a black-and-white series, but it appeared in the back of the second issue of the color Silver Star title before disappearing again into the darkness. The Missing Man, created with Mark Evanier, made several appearances in the back of Captain Victory and in Pacific Presents. The character exercised one of the more impractical powers in the history of superheroes — the ability to partially disappear, leaving behind, Cheshire-Cat-like, partially sketched facial features and rubbery stick-figure limbs — but he had considerable visual flair, with comic elements reminiscent of Will Eisner or Jack Cole. The Faceless Ones, done for First Comics with writer Jack Harris, lasted only three episodes in the back of Warp. Static, initially published by Eclipse, was a rare case of a character created and owned by Ditko. The character, who fought super-villains with the help of a hazardous force-field-generating suit, appeared in Eclipse Monthly #1–3 in 1983. Ditko took the series with him to Charlton in 1985 and finally to Renegade Press, which published three issues of Ditko’s World featuring Static in 1986.

In addition to publishing Static, Eclipse co-founder Dean Mullaney and his wife, Eclipse editor cat yronwode, proposed to do a retrospective of Ditko’s work called The Art of Steve Ditko. The original author dropped out of the project, but Mullaney and yronwode pursued the project with increasing enthusiasm after they tracked down biographical material using Ditko’s high school yearbook and made contact with one of Ditko’s brothers. Ditko had given his approval until he discovered that the scope of the book had expanded to include this biographical information. He angrily broke off his relationship with Eclipse, taking Static with him, and refused to cooperate any further on The Art of Steve Ditko. As fate would have it, the biography never saw the light of day. All the material gathered for the book was washed away without a trace in 1986 when a massive flood hit the town of Guerneville, California, and destroyed the Eclipse offices. Cue The Mocker laughing as he fades to black.

As the 1990s began, Jim Shooter, who was running Valiant Comics after being ousted as Marvel’s editor-in-chief, became a steady source of work for Ditko. Between 1991 and 1992, Ditko worked on Valiant’s Shadowman, World Wrestling Federation, Magnus: Robot Fighter, Solar and X-O Manowar. Valiant dropped both Shooter and Ditko in 1993, but Shooter launched another line, which he named Defiant, in 1994. Ditko was invited to work on the new line, but produced art for only a single issue of Dark Dominion before walking away from the company. As Shooter has explained it, Ditko objected that the premise of the Defiant world was “Platonic” in its assumption that ideal or phantasmal forms exist behind the surface of the real world, whereas Ditko considered himself Aristotelian, in that he believed the real-world surface is all there is. He took a similar stand when offered work by editor Ron Fontes on an indy anthology title featuring a vampire. The creator of Doctor Strange and artist on countless Marvel, Charlton and Warren horror stories cited objectivist principles in his refusal to work on any story that featured supernatural elements.

In 1993, between the two Shooter engagements, Ditko produced a 29-page comic for Dark Horse called The Safest Place in the World. The story, involving a menace-exposing microfilm protected by heroic individuals in the face of evil Eastern European security forces, incorporated many of Ditko’s habitual themes and was essentially a one-man project. It was owned by Ditko and later reprinted in black white by Ditko and Robin Snyder.

In 1994, working with scripter Roy Thomas, Ditko penciled and inked issues #1–4 of Jack Kirby’s Secret City Saga (absent only from issue #0) for Topps, as well as the first and only issue of Captain Glory. Both titles were based on concepts invented by Kirby. Ditko also inked Batton Lash’s pencils on a Wolff and Byrd story in Satan’s Six #1. The following year, Ditko penciled all four issues of Marvel’s Phantom 2040, an adaptation, with writer Peter Quinones, of the animated series. A couple of filler stories featuring, respectively, Iron Man and Sub-Mariner in 1998 were his last work for Marvel. Ditko produced two issues of material toward a projected ongoing series called Steve Ditko’s Strange Avenging Tales to be published by Fantagraphics in 1997, but only the first issue appeared before the project ran afoul of a production error and Ditko’s unforgiving nature.

The 1990s and the new century were a period in which Ditko gradually disappeared from mainstream comics. He continued to draw, but his work was harder and harder to find, reaching only an increasingly rarefied audience. He was like The Missing Man: there and yet not there. He was in the phone book for anybody to call, but a closed book to any fan, journalist or historian who tried to shine a light on him. In a sense, he had ceased to interact with us for a long time. The world he drew didn’t look like the world we were living in. Even into the 21st century, his characters, with their fedoras and bobby sox, continued to dress and groom themselves as if they still inhabited the world of Ditko’s youth. Even Peter Parker in 1962 had looked like he belonged to an earlier era. It was as if Ditko had locked himself in his studio in the 1950s and continued to draw from memory alone.

There’s nothing unusual, of course, about an artist withdrawing from the marketplace in his senior years. Ditko was after all, in his 70s when the century turned. The remarkable thing was how much he continued to apply himself to his art, still conjuring up new characters and using them as conduits for philosophical expression, even as he approached his 90s.

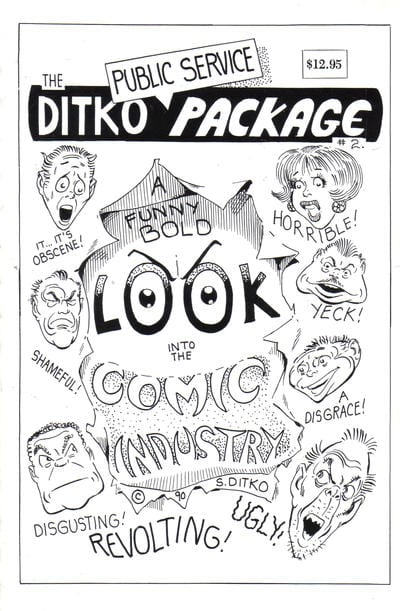

In editor/writer Robin Snyder, Ditko found what may have been his closest and most enduring relationship since his studio-sharing days with Eric Stanton. Their professional connection went back to 1983, when Snyder edited Ditko’s work on Archie Red Circle titles like The Fly and The Mighty Crusaders. In 1985, when Ditko left Eclipse for Charlton, Snyder again edited Ditko’s stories in Charlton Action featuring Static. And after Charlton shut its doors for good, Snyder oversaw Ditko’s transition to Renegade Press, working with the artist on titles like Revolver, Murder and Static. Their rapport was great enough that when Renegade suspended publication in 1988, Snyder and Ditko decided to self-publish a black-and-white collection of Ditko’s Static stories. This was followed in 1989 and 1990 by more cheap, black-and-white trade paperbacks mixing repackaged reprints with new material, including The Ditko Public Service Package, a 112-page slash-and-burn commentary on the comics industry mostly in comics form. And when mainstream venues finally dried up for Ditko at the end of the century, these Ditko/Snyder-published collections were the format he returned to.

By this time, most of Ditko’s 1950s-era contemporaries in the comics field had died or retired, but for the next couple of decades, Ditko, with Snyder, continued to issue regular “packages” of new and old work — approximately 20 more titles as of 2017. With little or no distribution to comics shops, the books were sold by direct mail order and eventually Kickstarter was used to raise funds and connect with readers. The creator-owned character he returned to most frequently was Mr. A, who had been spelling out Ditko’s ethical principles since 1967. In a sense, Mr. A, with his merciless, cocksure enforcement of an absolute moral code, fit right in with such contemporary antiheroes as Judge Dredd, Marshal Law and Frank Miller’s Batman. (Miller had proposed to collaborate on a Mr. A series with Ditko in the early 1990s, but Ditko had declined.) Except that Ditko didn’t consider the character to be an antihero. To Ditko, Mr. A was a rare pure hero in an age of moral wimps and super-powered alcoholics.

Interviewed in the documentary In Search of Steve Ditko, writer Alan Moore described the character of Rorschach in Watchmen: “Even if his politics are completely mad, he has this ferocious moral integrity … that was my take on Steve Ditko.” Moore, whose original proposal for Watchmen would have essentially killed off the Charlton superheroes, told interviewer Jon B. Cooke in Comic Book Artist #9, “I have to say I found Ayn Rand’s philosophy laughable. It was a ‘white supremacist dream of the master race’ burnt in an early 20th-century form. … I at least felt that, though Steve Ditko’s political agenda was very different to mine, Steve Ditko had a political agenda, and that in some ways set him above most of his contemporaries.”

Ditko would seem to have been as faithful a follower of Randian philosophy as Rand could have wished for. It’s not hard to find contradictions in Ditko’s logic, but he could never be accused of hypocrisy. When movies based on characters he had been instrumental in creating began earning millions of dollars for their corporate owners, he made no attempt to claim a share in the profits. He even declined to support the campaign for Marvel to return Jack Kirby’s original art. He seemed to have little interest in fame or wealth, asking only that be allowed to practice his art in his own way.

As fans, we think we’re entitled to know everything about our heroes, but Ditko had nothing but disdain for this hunger. If he had no time for us, it may have been because he believed, perhaps rightly, that we were a distraction from his work. But still he kept reaching out to us, to anyone who was still listening, through his art. Now that Steve Ditko, the man, is gone, his life’s work is what we have left: just the way he always wanted it.