We have yet to appreciate Ditko the philosopher, Ditko the comedian. Many comic-book readers lament the artist’s move away from formulaic superhero stories into the uncharted terrain of the philosophical comic. “Why couldn’t he just do something like his Spider-Man or Doctor Strange comics?” wonders the bemused fan when confronted with medium-reinventing works like 1969’s “The Avenging World” or 1975’s “Premise to Consequence.” Readers puzzled by Ditko's independent work or frustrated with its Ayn Rand-based politics should take a hint from the spirit of these comics: read them with a black sense of humor.

Ditko created these works at a revolutionary moment in US comic book history, the era of Underground Comix, when counter-culture cartoonists rejected the practices of the comic-book industry—a business committed to safe stories for children—by producing and distributing visionary work in new ways. When Ditko rebelled against the corporate constraints of Marvel and DC, he created moral tales that look nothing like the sex- or drug-fueled romps of his subversive contemporaries. But Ditko shares with them a radical, almost absurdist sensibility and a dedication to reimagining the medium’s formal and political possibilities.

I. It's a Sick, Sick, Sick, Sick World

The humor of Ditko’s auteur work is not the cocktail banter of Spidey and Doc Ock mid-battle

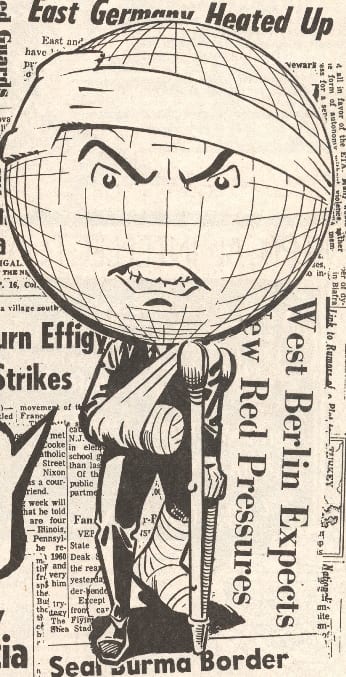

but the dark wit that’s possible only when something deadly serious is at stake.[1] Ditko is a believer—and he believes in the absurdity of ‘things as they are.’ Peter Parker worries about Mary Jane, Aunt May, and the villain of the month. But Ditko worries about The World. It’s sick, and moral sickness demands the sardonic punch of “sick humor.” With a giant bandaged globe for a head and a bunch of broken bones, the narrator of “The Avenging World” could be a mascot for much of Ditko’s independent work, and even some of his corporate comics.

but the dark wit that’s possible only when something deadly serious is at stake.[1] Ditko is a believer—and he believes in the absurdity of ‘things as they are.’ Peter Parker worries about Mary Jane, Aunt May, and the villain of the month. But Ditko worries about The World. It’s sick, and moral sickness demands the sardonic punch of “sick humor.” With a giant bandaged globe for a head and a bunch of broken bones, the narrator of “The Avenging World” could be a mascot for much of Ditko’s independent work, and even some of his corporate comics.

He’s symbolic of a world whose humor is black and whose heroes are morally (and literally) black and white: Ditko was angered when a fan diluted the purity of his hero Mr. A by printing an image of him on colored paper.

On “The Avenging World”’s opening page, the globe, with eyebrows arched and teeth clenched, looks directly at readers, chastising them and others for continuing to make his “condition . . . worse” (1).[2] Ditko creates nine portraits of those responsible for the world’s sickness that, taken together, form his “Rogues Gallery.” He replaces the fantasy menaces of, say, Spider-Man’s gallery (The Green Goblin, The Sandman, The Vulture, etc.) with caricatures of social types, such as the Middle Roader, the Humanitarian, the Neutralist, and the Enlightened, a hippie with a flower in its hair and a skull-like visage:

(This hollow face reminds us that Ditko’s jokes have death—the black humorist’s favorite subject—as their punch line.) In his rendering of these characters, Ditko revels in tropes of cartoony drawing, displaying forms of distortion, exaggeration, and excess long associated with visual comedy, all inked in a controlled, rational line that drips with contempt. Ditko’s villains often think of themselves as quite funny, and they are both funny-looking and morally grotesque. Many, such as the Neutralist, sport the grin of Dr. Seuss’s Grinch,

a facial expression that marks their villainous role in Ditko’s political masquerade.

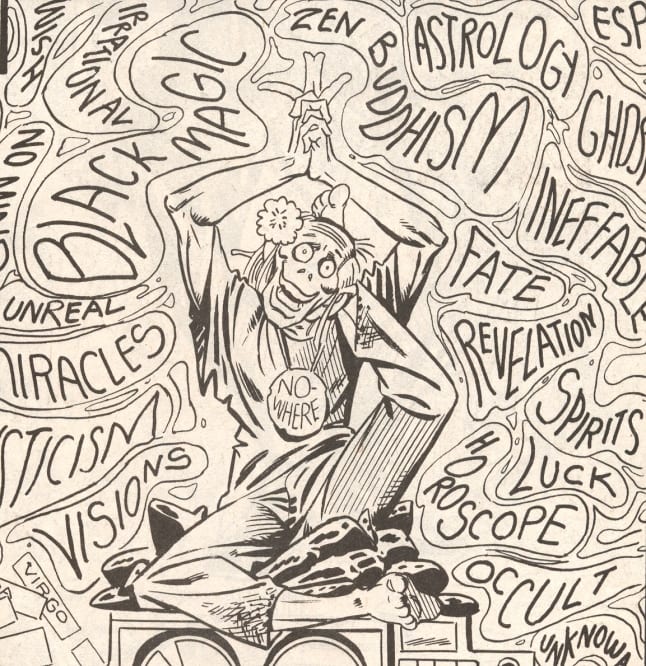

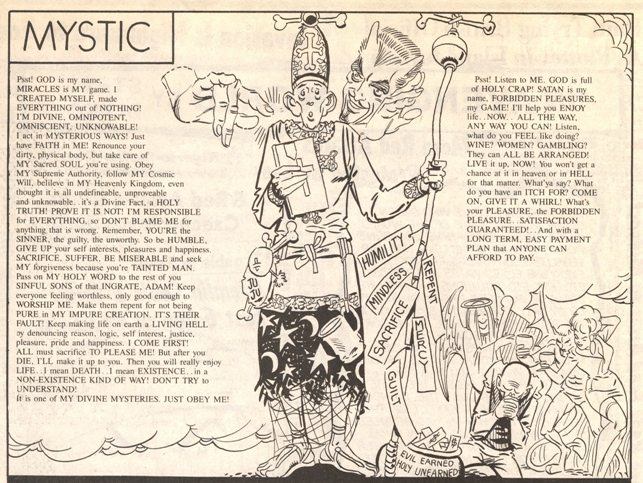

“The Avenging World”’s first satirical victim is the Mystic, a big-eared, bewildered fool who wears a motley outfit assembled from the wardrobes of the papist, pagan, and ju-ju fetishist:

Ditko’s God confesses to the Mystic that he’s a cosmic con man: “Psst. God is my name. MIRACLES is MY game” (2). Life sucks, he admits, “but after you DIE, I’ll make it up to you” (2). Even Satan sees this for what it is: “HOLY CRAP!” (2). The Mystic’s outfit is adorned with bones, perhaps the last remains of those who once believed as he does. Though he doesn’t recognize the meaning of his sartorial choices, the bones identify the Mystic as a member of what Ditko would see as a death cult, a group of believers whose philosophy is fundamentally anti-life. Religion, the cartoonist tells us, is tragedy for the living-dead, while black humor is comedy for the living.

Unlike the Mystic, the Humanitarian—a morbidly obese, relentlessly sobbing, well-dressed do-gooder—is not a super-naturalist. His flaw, though, is similar: he believes in abstractions. As unassailable proof of his sincere concern for others, his tear-soaked word balloons weep. In a panel that recalls Swift’s satirical endorsement of cannibalism in “A Modest Proposal,” the Humanitarian watches suffering people paraded into a vast “state machine,” a bureaucracy that works like a blender/meat grinder, extruding a single drop of nourishment per person:

Ultimately, the Humanitarian and all members of the rogues gallery wear symbols of the dead because their irrational beliefs, Ditko argues, are purchased at the expense of the living.

The mission of “The Avenging World” is to expose the comic absurdity—and the misery—that results from believing in anything (even humanitarianism) other than the rational self: rejecting our rational nature, we metaphorically eat each other and ourselves alive. Behind Ditko’s satire lies a utopian impulse; he’s offering a secular “revelation” of “The Truth,” of what he would simply call “the facts.” In one very anti-utopian tableau, a villain stands on a heap of anguished human forms created by ink outlines over newspaper text: we are prisoners of the words we believe:

And the philosophical comic, which exposes false beliefs, can free us. If it fails to meet this lofty goal, at least it serves up a few sick laughs.

In a 1968 story from the fanzine witzend, Mr. A diagnoses the world’s bleak and bilious moral condition: “A cancerous sore becomes too unsightly so we cover it up, hoping it will just go away while we look for some other disease to cure . . . . The hidden diseases are spreading unchecked, contaminating everything until no healthy area remains. Not in a man, not in a society!” (2). A few panels later, thugs repeatedly punch Mr. A’s alter-ego Rex Graine in the gut and kick him in the face, acts of violence that spawn a barrage of wordplay based on the metaphor of sickness. These hoods believe that violence is a “treatment” that cures the spread of heroism, and they make a threat: if Graine refuses to take their dollar “bills” he will soon have to pay some hefty doctor “bills” (3):

And criminals are not the only ones who have sick fun with words. Shortly after this scene, Mr. A delivers a little gallows humor, taking the hoods’ violence to its inevitable conclusion: death. He promises to transform a criminal’s “net of protection” into a “noose around his neck” (5).

The Mr. A stories (as well as those featuring The Question or The Mocker) show a debt to 1940s and ‘50s crime comics, which, as one of comics’ best critics Frederic Wertham has noted, are marketed on a lie. The publisher tacks a moral on the end of a story featuring fisticuffs, bondage, and decapitation (or he titles the comic Crime Does Not Pay), believing parents will assume it’s an upright tale of justice. Yet in these stories, crime does pay. The young reader is rewarded with physical sensations caused by viewing unrelenting violence that, like scarfing a bowl of sugary cereal, keeps ‘em coming back for more. The images in these comics may be sick and their plots ironic, but the irony never reaches beyond the page to prod, provoke, or punish the world. These comics don’t believe in anything.

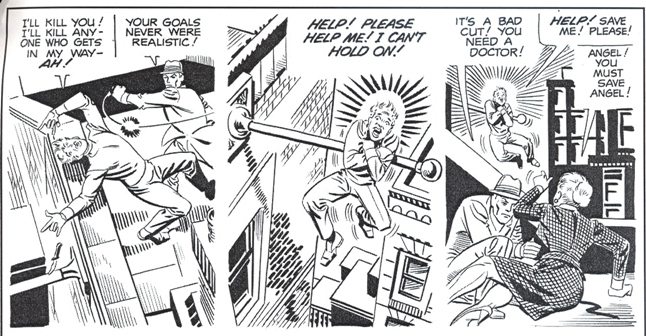

But Ditko’s comics do. They twist conceits of crime comics and morality plays into serious gags, offering an ethical critique typical of the black humorist, who wrings irony-based visual and verbal laughs out of deeply unfunny situations. Ditko’s naming practice parodies the transparency of traditional allegories, in which a character’s name tells his or her story: Faith is faithful, Temptation is tempting, etc. While many of Ditko's names signify a character’s key trait, other names are ironic, and still others are misleading in ways the cartoonist hopes will be illuminating. The crime boss Baggot, for example, acts like what his name sounds like: a maggot (his minions are metaphorical “leeches,” “parasites,” and a rodential lackey named Roden). The ironically named Purity is an Assistant DA who goes bad. And Miss Kinder is kind, but, like the Humanitarian, foolishly kinder than she should be. Blinded by a desperate desire to help others, Kinder fails to see that a thug named Angel is anything but angelic. And there’s another irony in his name: angels fly, but Angel can’t. He plummets to his death from a building’s flagpole in the final panel, the sacred home of a comic strip’s punch line. As he hangs onto the pole, the emotion lines around his head form a mock halo:

Shortly before Angel dies, Mr. A lands a punch on his jaw. The hood screams “AH,” an expression that inverts the classic cartoon laugh, “HA.” Death, laughter, and justice are siblings in Ditko’s work. If black humor transgresses taboos, what could be more transgressive in 1969 than a comic book hero watching someone he could have saved die, and then feeling pretty good about it?

II. The Creep and the Maniac

Did Mr. A laugh beneath his mask as Angel fell? [3] Ditko’s Creeper certainly would have. [4] At the end of “Menace of the Human Firefly!” the villain plunges from atop a lighthouse. At first, the Creeper “stands stunned and silent,” but quickly his mood changes: he “laughs a long chill mocking laugh” (18):

His laughter (far weirder than that of his pulp precursor The Shadow) is a bizarre reaction to a death that had just stunned him into silence: who or what is chilled by it (does it evoke the “chill” of death?); who or what is mocked? (the dead villain, life?). Most important, why does the Creeper laugh at all? Perhaps it’s hard to reconcile (to adapt a line from Lenny Bruce) “what should be”—the criminal brought to justice—with “what is”—the criminal dead. Maybe all that’s left to do is laugh.

The cackle that arises from this irreconcilability is, not surprisingly, troubled and excessive: it’s the maniac’s laugh, a mixture of elation and dread. The Creeper constantly jokes and laughs as part of his performance—it’s a way to unnerve his opponents. Yet when he laughs after The Firefly dies, there’s no crowd for the comedian to work. Mania overtakes him. He can’t reconcile comedy and tragedy. Like those who suffer from mania, the Creeper often displays an irrational and excessive enthusiasm. And, as he admits in other stories, he loses part of himself in the part he plays. He acts “the maniac,” but then becomes one. Recognizing that irony, sickness, and comedy are everywhere can turn a comedian, or a thinking superhero, into a bit of a maniac. And excessive, maniacal laughter visually dominates the Creeper stories:

In some panels Ditko hand-letters more than 40 HAs, and one story feature nearly 150. The HAs often spill out of the panel and across the gutters, violating the borders and margins that rationally order the grid of the comic page. The Creeper’s laughter literally can’t be contained.

The Creeper’s mania is often an unconscious response to a character’s death, but even when he self-consciously parodies super-heroism by adopting and exaggerating its visual and verbal conventions (a very costumey costume and lines like “Taste my vengeance, Scum!”), his rhetoric articulates a tension at the heart of black humor: contraries (like pleasure and pain) merge into a complex of meanings and sensations that the Ego can’t assimilate. The Creeper threatens a villain with a punishment he would never dish out, but the villain is certain he will: “I’m going to make sure you experience such extreme pleasure that you’ll die laughing” (“The Disruptor” 8):

This line comes straight from the repertoire of 1940s and ‘50s horror comics, but filtered through Ditko’s imagination, such familiar tropes get a philosophical makeover. Horrified by the thought of the paradoxical “laughing death,” the villain flees, screaming for help from a criminal Ditko mocked in “The Avenging World”: “Oh, God!” (8). The Creeper’s comedy shows his audience that death, and the thought of it, can be creepy and funny—if you’re in on the joke at God’s expense.

III. The Comedic Silent Narrator

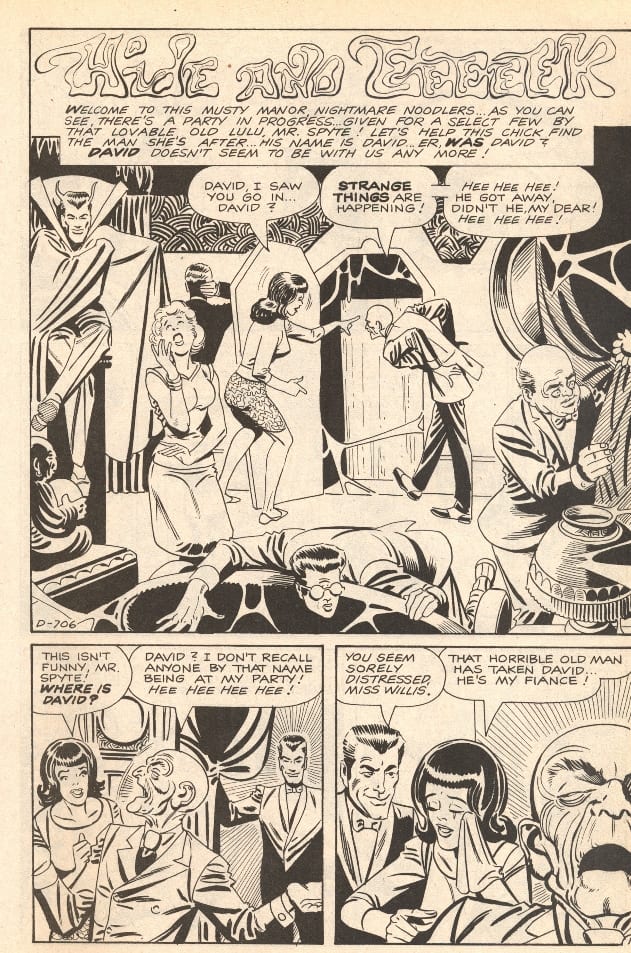

The stories Ditko drew for Charlton Comics in the 1960s and ‘70s feature conventional plots of haunting and murder, but the cartoonist makes things strange by giving the familiar “horror host” a philosophical and comedic makeover. [5] Typically, this character’s role was limited to cracking a joke or two when introducing and concluding a story. Ditko had expanded the host’s role in his 1950s “Mysterious Traveler” stories and elsewhere by drawing the Traveler throughout the tale: he appears in gutters between panels, in the background of images, or even as the panel in which the scene takes place. He’s both inside and outside of the narrative, a character with god-like, third-person omniscience and omnipresence. The Mysterious Traveler typically doesn’t laugh; rather he looks disinterested, concerned, or angry.

Ditko’s later horror narrators share these expressions, but they grin, smirk, and laugh—even maniacally. Physically positioned within and above the story, the narrators become Black Comedians who see the humor we miss. Though the Charlton horror comics lack the political content of the Objectivist-inspired work, they dramatize new ways of looking—and laughing—at violence and death.

“Someone Else is Here!,” scripted by frequent Ditko collaborator Joe Gill, travels common ground. Newlyweds move into a house haunted by a beautiful ghost, and with each consecutive scene, the malicious wife grows more devious and the passive husband more frustrated, making the end fairly predictable: the wife gets “replaced” by the spirit. But to see this through the pantomime of the narrator, Mr. Dedd, is to see a story (and an approach to narrative and page layout) that’s stranger than the plot would suggest. The narrator’s visual “intrusions” function as extradiegetic reaction shots, in which his responses bear a curious relationship to the scene he’s viewing:

Ditko chooses expressions and gestures that echo, magnify, obscure, and sometimes contradict the violent and emotional content of the story panel. Dedd smiles at moments that, at first, don’t seem all that funny. Then he grins almost demonically, looking uncomfortably like the evil wife. When he watches a scene that should evoke emotion—the unhappy husband wandering alone—his face shows no expression.

In other intrusions, Ditko reveals more than just the narrator’s face: we see him with fists clenched or cape raised to obscure his expression (what’s he hiding?), or posed in gestures that intensify the emotional tone of the action. Near the end of the story a two-faced Dedd looks apprehensively to the left (into the narrative past) and grins intensely toward the right (into the future), a facial transformation that resembles the Creeper’s turn from sober reflection to maniacal laughter at the end of the Firefly story. No matter the expression, there’s just something funny about having a mysterious omniscient narrator pop up and shake his fists at a character or cover his face because he finds a scene too horrifying to watch. With all of these gestures, Ditko asks us to consider the ways that serious moments and themes—abuse, violence, death, and justice—can be strangely comedic.

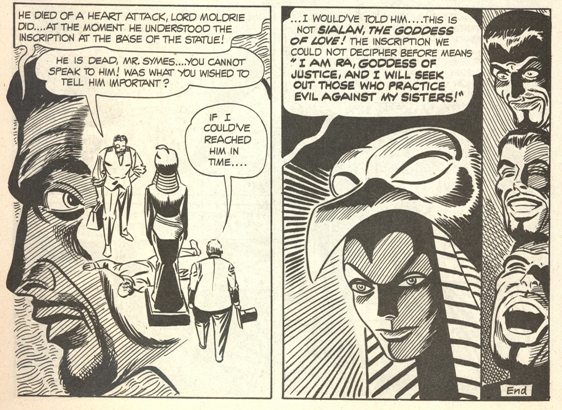

Dr. Graves, another Charlton host, haunts “An Ancient Wrong,” drawing our attention to the humor and pathos in the story by making a joke out of a dark situation, and by appearing, like Mr. Dedd, where we least expect him. The tale’s villain, Lord Moldrie, makes a fundamental mistake. He believes he has stolen the magical statue of the Egyptian Goddess of Love but has actually boosted the Goddess of Justice. Moldrie is a hate-filled criminal, yet Ditko shows us his desperation as he looks for what most of us seek: love. In scenes pathetically funny, he sleeps in a mummy’s coffin placed at the goddess’s feet and later “tended . . . lovingly” to the lifeless statue (6). As Ditko scoffed at the Mystic for believing in god, he ridicules Moldrie for worshiping the dead. Graves doesn’t crack one-liners, rather he reveals, almost solely by facial gestures, what’s inherently farcical in the story and in the world—the absurdity and irony that envelopes us, but often goes unnoticed. Near the tale’s end, Moldrie looks into the eyes of Justice and, realizing his mistake, dies instantly. In the final panel, Ditko draws three faces in which Graves’s grin transforms into a full-blown, Creeper-esque maniacal laugh, with mouth fully open, eyes closed, and head tilted back:

The narrator’s faces slightly overlap, forming a kind of montage, which visually represents the complexities and contradictions present in his reactions to the story’s themes. The other characters find Moldrie’s death a somber occasion, but not our host, who knows what they don’t: the weirdly funny way the tale mixes, but never quite reconciles, love and longing, justice and death.

[A three-face inter-panel sequence: from "The 9th Life"]

Ditko’s Charlton stories, like his independent comics, have a philosophical aspect: they want us to recognize that things are not always what they seem, that seemingly familiar plots can be strikingly strange. Ditko disrupts the plots with visual intrusions to remind readers to pay attention to, and see black humor in, the story’s bleak scenes. On the cover of a collection of his Charlton stories, Ditko highlights their formal inventiveness, calling them “an experience in . . . story/art techniques.” One of the few photos of the cartoonist shows him at work, near a sign that says only “Think.” The narrators’ gestures can be seen as Ditko’s advice to readers to think about the effects of his formal choices. He wants us to realize that Graves’s and Dedd’s approach to watching the plot unfold is not that of a child reading for stimulation, but an adult deliberately looking, leering, and laughing at tales of death.

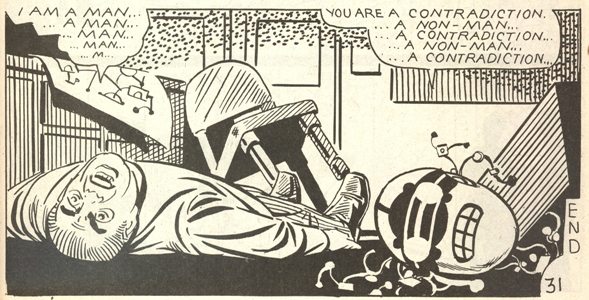

IV. Conclusion / Contradiction

Throughout Ditko’s Charlton stories, his auteur work for DC, and his black and white comics, he dramatizes an abiding concern with the psychological effects of contradiction.

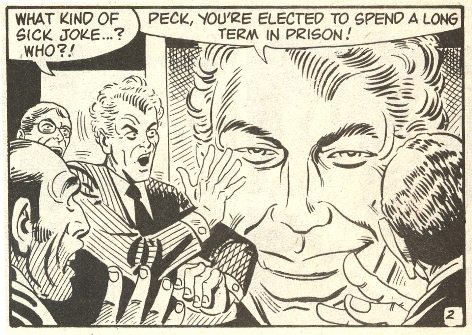

He insists that the slightest inconsistency in philosophical beliefs is destructive to the believer. Yet he also knows that our inconsistencies are endlessly productive: they’re the polluted spring that feeds the comedy of the black humorist. It might seem odd to mention Steve Ditko alongside of R. Crumb or Lenny Bruce, two figures whose counter-cultural views are anathema to the man who created Mr. A, the black and white embodiment of moral perfection and philosophical consistency. But like them, Ditko attacks the status quo, ridicules government and religion, exposes hypocrisy, and, most importantly, sees irony and humor wherever he looks. Early in his graphic novel The Mocker, a giant poster with a politician’s face appears to laugh: “HA! HA! HA! HA! HA! HA!” Shocked by the laughter, a character yells, “What kind of sick joke . . . ? Who?!” (2). It’s Ditko, the mocker.

He insists that the slightest inconsistency in philosophical beliefs is destructive to the believer. Yet he also knows that our inconsistencies are endlessly productive: they’re the polluted spring that feeds the comedy of the black humorist. It might seem odd to mention Steve Ditko alongside of R. Crumb or Lenny Bruce, two figures whose counter-cultural views are anathema to the man who created Mr. A, the black and white embodiment of moral perfection and philosophical consistency. But like them, Ditko attacks the status quo, ridicules government and religion, exposes hypocrisy, and, most importantly, sees irony and humor wherever he looks. Early in his graphic novel The Mocker, a giant poster with a politician’s face appears to laugh: “HA! HA! HA! HA! HA! HA!” Shocked by the laughter, a character yells, “What kind of sick joke . . . ? Who?!” (2). It’s Ditko, the mocker.

_______________________________________________________________________

A slightly different version of this essay, without images, first appeared in

Ryan Standfest's anthology Black Eye.

Works by Steve Ditko Discussed:

“An Ancient Wrong.” The Many Ghosts of Doctor Graves #20 (1970). Reprinted in Steve

Ditko’s 160-Page Package (1999).

“The Avenging World” (1969). Reprinted in Avenging World (2002).

“The Disruptor.” World’s Finest Comics #251 (1979). Reprinted in The Creeper (2010).

“Menace of the Human Firefly!” First Issue Special #7, 1975. Reprinted in The Creeper

(2010).

The Mocker, 1989.

“Mr. A.” witzend #3 (1967).

“Mr. A.” witzend #4 (1968).

“Premise to Consequence.” ..Wha..!? (1974). Reprinted in Avenging World, 2002.

“Someone Else is Here!” Ghostly Tales #86 (1971). Reprinted in Steve Ditko’s 160-Page

Package (1999).

___________________________________________________________________

[2] “The Avenging World” was first published in 1969, and Ditko has added new sections and revised it a number of times since then. It is a vastly underappreciated and historically significant achievement in comics formalism, combining narrative and non-narrative sequences with diagrams, elaborate splash pages, detailed and abstract figuration, extended text passages, and collages.

[3] Baggot, Roden, and Purity appear in “Mr. A,” from witzend #4 (1968); Miss Kinder and Angel appear in a story also titled “Mr. A,” from witzend #3 (1967).

[4] Ditko created the Creeper for DC in 1968, around the time he began to publish Objectivist-based philosophical comics such as the Mr. A stories and “The Avenging World.”

[5] The Charlton stories I discuss were published in the early 1970s, shortly after Beware the Creeper ended in 1969 after six issues.