These were the kinds of limitations the museum was dealing with when it was approached by the Art Students League with an offer to transfer its collection of World War II anti-Axis propaganda cartoons to MoCCA. This “Cartoons Against the Axis” collection, which included work by Charles Addams, Peter Arno, Syd Hoff, Crockett Johnson and many others, had first toured the country in 1942 as a war-bond-boosting exhibit organized by then Art Students League Men's President Gregory d’Allessio. D’Allessio’s widow Hilda Terry, known for her Broom Hilda Teena comic strip, agreed to the collection’s acquisition by MoCCA. Sixty-three years after its first exhibition, the collection was displayed at MoCCA in a show that ran from Oct. 8, 2005 to Feb. 6, 2006. In an essay accompanying the exhibit, Art Spiegelman wrote, “As a group these drawings offer a complex and unsanitized range of cartoon art: cartoon as propaganda, as joke, as graphic design, as witness, as howl of anger, and sometimes even as Art.”

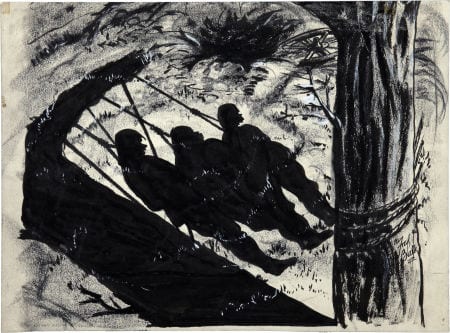

It was the last time the cartoons would appear in public as a group. Within three years of acquiring the collection, MoCCA began auctioning off pieces of the collection to the highest bidder. The cartoon that had best evoked the juncture between propaganda and art for Spiegelman was a painting by Saul Steinberg. “It shows Der Fuhrer as an unprepossessing Teutonic knight with a small Mussolini strapped to a shield pierced with arrows,” he wrote. “Hitler is mounted on a horse that wears a Nazi Helmet and a swastika-patterned blindfold. … The damned horse has some of the pathos of Spark Plug (the horse in Billy DeBeck’s 1920s Barney Google strip) but also somehow echoes the tortured equine in the world’s most memorable anti-axis cartoon: Picasso’s Guernica.” The Journal has confirmed that the Steinberg painting was sold through Heritage Auctions for $8,604 on June 5, 2008. Other pieces from the collection, including one by William Henry Cotton were part of the same auction. In 2009, eight other “Against the Axis” cartoons, including work by Ben Roth, Fred Balk, Frank Beaven and John Groth, were auctioned through Heritage.

MoCCA is chartered by the State Education Department and operates as a nonprofit art museum. In its mission statement, it pledges to “collect, preserve, educate, and display cartoon and comic art.” Breaking up a unique, historically important collection and selling it off piecemeal does not, on the face of it, seem to be in keeping with the goals of an art museum, so the Journal consulted the American Association of Museums, the Association of Art Museum Directors and the Association of Art Museum Curators. As it happens, museums had gone through a decades-long process to establish a code of ethics. In 1984, the American Association of Museum’s Commission on Museums for a New Century decided that more emphasis should be placed on public service and education and an Ethics Task Force was appointed. After several years of debate and discussion, a finalized AAM Code of Ethics for Museums was approved in 1993. An individual museum was expected to come up with its own code of ethics that would be in conformance with the AAM’s code. In relation to collections, the Code required a museum to ensure that:

Collections-related activities promote the public good rather than individual financial gain.

Collections in its custody are lawfully held, protected, secure, unencumbered, cared for and preserved.

Acquisition, disposal and loan activities are conducted in a manner that respects the protection and preservation of natural and cultural resources and discourages illicit trade in such materials.

Disposal of collections through sale, trade or research activities is solely for the advancement of the museum’s mission. Proceeds from the sale of nonliving collections are to be used consistent with the established standards of the museum’s discipline, but in no event shall they be used for anything other than acquisition or direct care of collections.

Spokespersons for the American Association of Museum Directors confirmed to the Journal that funds from “de-accessioning,” that is the sale of collection items, can be used only for the acquisition and care of other art, there can be no sales to museum administrators or staff, and all living artists or donors must be notified if their art is being de-accessioned. Also, any art in the possession of the museum must be made accessible to the public.

Abramowitz is well aware of these rules and assured the Journal that they are being followed by MoCCA. “We can’t use the money from the sale of art for any capital expenses,” she said; “we can only use it for art-related purposes.”

Given that the few acquisitions that are taken on by MoCCA tend to be donations and considering the modest size and storage facilities of its permanent collection, the Journal asked what art-related expenses MoCCA could have that would justify the sale of art. “Just installing a show is very expensive,” Abramowitz said.

Abramowitz herself takes no salary as president and chairman of MoCCA’s board of trustees. The paid museum director position was replaced a couple of years ago by a part-time museum manager (Doug Bratton) and a full-time registrar, but Scalzi was let go last year to further reduce costs, leaving only one part-time manager position on the museum’s payroll.

The splintering of the “Cartoonists Against the Axis” collection is certainly a loss to comics history, but the entire blame for it can’t necessarily be laid at the fourth-floor door of the museum. Given its limited resources and staff, MoCCA was arguably not in a position to keep the collection safe and accessible without better funding. According to Abramowitz, “We were reluctant to take it. The collection was in poor condition to begin with and we could not have taken care of it all. It was before my time so I don’t know if it was her [Terry’s] intention for us to keep it or sell it, but it was a matter of having a museum or not having a museum. It doesn’t do any good to have a collection if you don’t have a museum to display it.” Klein said donors are always given an option of indicating whether the donated art can or cannot be sold.

The Art Students League was at the limits of its own storage capacity when it proposed to donate the art to MoCCA. With comic art museums closing right and left, the tragedy of the “Cartoonists Against the Axis” collection is that it ran out of options and was facing slow ruination or homelessness.

•

Abramowitz doesn’t want to be thought of as a heartless businesswoman who has no affinity for comics and is somehow getting rich in the comic-art-museum biz. She grew up reading comics and has an educational background in art. “I went to summer camp with the Harvey brothers,” she told the Journal. “Harvey comics were passed around the camp every summer. I remember reading Harvey and Archie comics under the covers with a flashlight after ‘lights-out.’ My brother was the superhero comics fan, which he collected and traded. As I grew older, I became a fan of Mad magazine.”

She has a BFA with an emphasis on photography and worked for a time in commercial photography in the ’80 and ’90s, but it was her eight years of late-career experience in commercial real estate that made her an immediate asset to MoCCA when she met Klein in 2003. “I served as MoCCA’s commercial real estate broker,” she said, “and convinced our current landlord, Jeff Gural, the chairman of Newmark Knight Frank, to donate our current space rent-free for almost a year. Our lease is still way below the current market due to Jeff’s generosity. However, the rent does go up annually and remains our largest expense.”

Abramowitz became co-vice chairman of MoCCA’s board of trustees in 2006, then was elected chairman and president in 2008, essentially filling Klein’s former role. As a real-estate broker, she knew that a place needed to look good if it was going to attract interest and that was her initial focus. Asked what her goals were for the museum when she took the reins, she said, “My goal was to improve the museum, to give it more credibility as a museum and to improve it in appearance. I closed the museum for six months to do that. And it turned out to be very successful.”

What improvements specifically? “Mostly physical,” she said. “The cleaning of the museum. I wanted to have a stronger feel of professionalism. I wanted it to feel like a place that people would want to treat like a museum. An artist could feel comfortable loaning their work or a collector or some other people would want their work to be donated here. And the first opening we had, I was shocked because when people came in here, they were whispering. We’d go, ‘Wow. They’re looking and they’re being quiet.’ I replaced a lot of the furniture in here. I threw away a lot of things that were collected that we didn’t need and I cleaned up the place and I painted and polished the floors. I made the place feel much more sparse. I wanted to treat it professionally. You answer the phone a certain way. The volunteers wore the MoCCA T-shirt. I created systems.”

Asked what her goals for MoCCA are today, she said, “To actively fund the museum. That’s our focus. To increase our staff. To relocate to a ground-level presence.”

She expressed surprise when the Journal suggested that building MoCCA’s permanent collection did not seem to be a high priority. “We get offers of art donations,” she said. “The permanent collection is growing. We have not been idle on it. But being able to exist is our first priority. It’s really hard to fund a museum in New York and to build a permanent collection. That’s the reality. If we were in Iowa, we would have a much bigger space and I would have four or five people. We desperately need to hire more people.”

The Catch-22 that museums labor under, as Mort Walker discovered, is that you can afford fine facilities in the wilds of Florida, but you don’t have access to the kind of community interest and funding possibilities that a publishing Mecca like New York offers. “I don’t have access to very much funding,” Abramowitz corrected the Journal. “The city doesn’t have it. The publishers don’t have it. The artists don’t have it. But I think having a museum in New York is really a special thing. I think it has an appeal to visitors and I think it has a great appeal to artists.”

Above all, Abramowitz wants you to know that, despite its longevity, MoCCA is not rolling in money. It continues to have to claw its way into existence day after day. Without more funding, it can’t afford a larger space and without a larger space it can’t expand or display a permanent collection. Under the circumstances, the imaginary contest-entry museum we considered earlier begins to look like a cruel joke.

•

In the fall of 2010, MoCCA was approached by prominent webzine SuckerPunch with an idea that would seem to promise much potential publicity and fundraising possibilities. SuckerPunch would challenge architects to design a new site for MoCCA, with the winning designs to be awarded cash prizes totaling $2,500 and publication on the SuckerPunch site. Abramowitz agreed to sit on the jury and provide a set of requirements for the project, including a 20,000-square-foot, flexible, modular museum space, four offices, two classrooms, a café, a store, a theater and a lecture hall. SuckerPunch announced the competition, even selecting an empty lot at the corner of Norfolk and Delancey Streets in the Lower East Side, noting, however, that the site was not owned by either SuckerPunch or MoCCA.

The contest drew eye-popping, utopian site and floor plans from individual architects and architectural firms from all over the world. The extravagant designs, with names like BLOP!!..POW!!..WIZZZZZZZ and Bubble Art Display, reflected both an aggrandized and a degraded view of what a comic art museum would be. The First Place entry by Volkan Alkanoglu, who was awarded $1,200, appears to have been an attempt to design a 20,000-square-foot Batmobile.

If you’re not a regular SuckerPunch visitor, it’s understandable if you’ve never heard of these proposed MoCCA designs or this contest. MoCCA did little to promote the event and no specific effort was made to raise funds to realize any of the architectural designs. “They were fantasies,” said Abramowitz. “It was fun for us, but we didn’t take it too seriously.” After years of dealing with New York real estate, Abramowitz has apparently learned not to think too big. It will be a long wait for that alternate-universe museum to “take shape.”

•

Now consider a third alternate-reality cartoon-art museum: This one has a permanent collection of more than 7,000 items, including etchings dating back to the 1700s, animation cels, and original strip art. Two of the museum’s five gallery spaces — 800 square feet out of a total of 3,200 square feet — are dedicated to showcasing the permanent collection, with one gallery set aside for animation and the other for everything else, including comic books, strips, editorial cartoons, undergrounds, etc. Archives not on display are kept in a second-floor collections room. Another three galleries totaling 2,400 square feet are devoted to nonpermanent exhibits. The museum also houses second-floor offices and a bookstore and offers educational workshops, lectures and after-school programs.

This museum, the Cartoon Art Museum, exists in the alternate universe that is San Francisco. Like MoCCA, CAM is a survivor. Founded by Malcolm Whyte, it began in 1984 as a moveable “museum without walls” setting up exhibitions wherever space became available, then acquired a permanent residence in the Yerba Buena Gardens cultural center in 1987 with the help of a Charles Schulz endowment. The building is not owned by CAM or by the city, however. Half of CAM’s annual budget goes to pay rent.

Much of CAM’s permanent collection was acquired during its first five years. According to CAM Curator Andrew Farago, “With that as the foundation, the collection has been building itself ever since.” Asked about the museum’s policy on selling donated art, Farago said, “We only sell artwork that is donated for that express purpose. If an artist donates a piece for one of our auctions, we’ll sell it, but anything that’s intended for the collection stays in our archives.”

As with Abramowitz and MoCCA, fundraising is a constant battle for CAM. “We’re always fundraising,” said Farago. “Always. I don’t think a week passes that we aren’t scheduling events, writing grants, meeting with funders or brainstorming with cartoonists or our board of directors about ways to generate additional income for the museum. We’re in the same boat as pretty much every other arts nonprofit right now, in that every year we’re still around is a good one. We’ve always operated on a tight budget, and that’s allowed us to adapt whenever we face downturns in the economy. Larger museums spend on a single show what I spend in two or three years assembling our exhibitions. We know what we’re doing, how to do it and how to operate within our means, and that’s been the key to surviving everything that’s come our way since 1984.”

Paid staff at CAM includes a curator, an executive director and a full-time bookstore manager, plus regular contractors: a skeleton crew that MoCCA would nevertheless envy. One advantage that has helped CAM get to its current position is the patronage of the Schulz family. “Jeannie Schulz is still one of our biggest supporters,” Farago said, “and I can’t imagine where we’d be without her ongoing efforts on our behalf.”

CAM struggles, but at the end of the day, it has accomplished much that we would want in a comic art museum, even if it isn’t shaped like the Batmobile. That is not to say that it is a shining beacon. In the broad spectrum of art museums in the U.S., CAM is not a top-tier institution. It still inhabits the ghetto reserved for mass-culture-themed museums.

Such museums face a unique set of challenges. One is the cultural glass ceiling that ensures that museums like MoCCA or CAM are never going to reach the same level of social respectability as a museum of high art (and are therefore not going to be high on the radar of most big-money donors). Another obstacle, however, is self-imposed: It is the way that mass-culture museums have allowed themselves to become inextricable from the commercial industry that owns many of the properties that make up the art form.

The high recognition quotient of properties like Batman and Archie is the ace up the sleeve of comic-art museums and they can’t resist playing it over and over. CAM is no different from MoCCA in this regard: It uses crowd-pleasing shows like its recent Image Comics retrospective and Art of Puss ’n’ Boots exhibit to subsidize shows built around edgier fare like editorial cartoonist KAL or LGBTQ cartoonists. Of course, art done for hire is still art, and there is every justification for an exhibition of art by, say, Dan DeCarlo or Steve Ditko. Unfortunately, the artists don’t have the same recognition quotient or nostalgic glow as the characters they worked on, so comic art museums tend to develop such shows around the properties rather than the artists.

Even major institutions like the Museum of Modern Art or the Brooklyn Museum are not above popular-culture exhibitions on subjects like Star Wars. But MoMA has the space to offer such shows while still displaying the permanent collections on which its reputation has been founded. Which brings us full-circle back to the problems of real estate and money.

•

When the Journal approached Abramowitz about doing a 10th anniversary assessment of the museum, it sparked a panicked exchange of internal correspondence at MoCCA wondering what sort of hatchet job the Journal had in mind and planning how best to stall the proposed article. (The Journal has seen the e-mails.) Abramowitz was not available when the Journal visited the museum and for the better part of a year, she kept the Journal at bay, pleading ill health and a busy schedule. All of which suggests a guilty conscience. But when the Journal looks at MoCCA — and it has had many months to look while striving to interview Abramowitz — it sees a worthy institution fighting an uphill battle to give comic art the respect it ought to have. Could Abramowitz and the board of trustees be doing a better job of generating public attention and financial support for the museum? Maybe. Certainly, it seems as though the SuckerPunch contest could have been better used to create publicity and inspire concrete funding proposals, and there are better ways to work media like the Journal than hiding from them. Nor is she particularly beloved by all of the museum’s various volunteers and curators, more than one of whom reported butting heads with her. But let’s face it. Abramowitz doesn’t receive a paycheck for what she does. She suffers the anxieties of a shoestring budget and harassing phone calls from journalists because she wants New York to have a decent museum of comic and cartoon art.

We know a comic-art museum with a viable permanent collection is possible, because CAM and San Francisco have made one. But ultimately, the only way that MoCCA will grow the way that it needs to is if the comics community holds the museum to high standards, supports the achievement of those standards and makes the City of New York show respect for its native son: the comic art form. Right now, MoCCA is a long way from putting a crack in the cultural glass ceiling, but the worst that we can say about it — and the best that we can say — is that we will have the comic-art museum that we deserve.