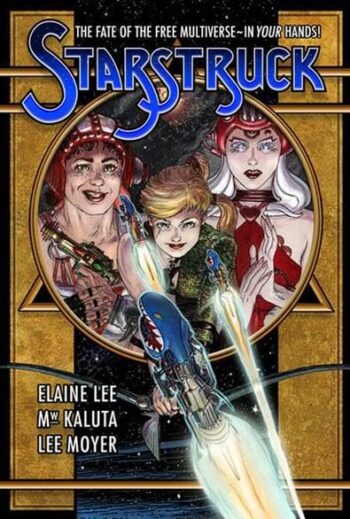

Elaine Lee and Michael Kaluta’s Starstruck had almost become the stuff of legend; now it is in print. The first page of Starstruck was published more than 30 years ago, followed by a complicated serial publishing history. The first 200 pages are now collected in one immaculate book, with an almost equal amount of excellent additional material.

From the fan’s perspective, the progress of Starstruck seemed to have stalled some time ago, forever “to be continued,” never to be definitively collected. Now it is collected, and it turns out, Lee and Kaluta have been moving forward with full development of the next two-thirds of the story. Starstruck, as we’ve known it since 1980, really is finally complete, and the rest of the story will finally be told.

Now seemed to be the ideal time to have a long conversation with Lee and Kaluta, both about the genesis and development of the book and about the intricacies of the story itself, which spans decades and is told with the ambition and complexity of Watchmen or a Faulkner novel.

My intent going into this interview was to break with the tradition of reintroducing Starstruck to the uninitiated, and instead simply talk to the creators about their work. There’s never been an extended authors’ preface to Starstruck.

But we’re not leaving those unfamiliar with the story out in the rain. Lee and Kaluta are gradually posting the IDW pages on their website, so you can start reading Starstruck right here. (The website also includes a glossary for the Starstruck universe, which has been developed far beyond the scope of the comic book pages.)

I’ll preface this first installment of the interview with only a few pieces of backstory: Starstruck started as a play, written largely by and starring Lee, who was an established television actress and emerging writer. Kaluta, one of the most interesting and elusive comic book artists of the Seventies, entered the picture at that point, having become disillusioned by the comics industry but enthralled by the idea of designing Starstruck’s costumes and sets. Before long, Starstruck crossed the event horizon into comic books, Lee becoming a regular contributor to the form, and Kaluta entering into the longest, strangest narrative of his comic-book career.

TCJ: How does it feel to have finally signed off on, and published definitively, the first 200 pages of the Starstruck?

Elaine: Wonderful! I’m very happy with it. And Lee Moyer’s beautiful color adds so much to it. Of course, as soon as it was out, I saw a few small mistakes we allowed to get past us. It always happens, I suppose. But that really is being very picky. And there will be more! As the Galactic Girl Guides might say, “Trust me.”

Michael: Having the first third of the Starstruck Story in color and published in a massive hardback gives me a “between worlds” feeling. One part of me says “can it BE?” and the rest of me is peacock proud. It’s a heck of a lot of work to have all in one place (but knowing there’s an equal amount of work already drawn, just waiting for the intervening pages to be drawn: well, again a metaphor: like watching the Amazing Sunset from one’s desert island then glancing over one’s shoulder and seeing a full-sized Saturn rising out of the Ocean behind. Yeeeeek!

TCJ: I’m not aware of any other example of graphic storytelling that was developed in quite the way the work in this volume was. The story in its present form is 200 pages long, but the first and last pages of it are the same pages that bracketed this story arc when it was half that length. After the series’ first American run with Epic (which reprinted the earliest chapters as an early graphic novel, then added six new issues), you decided to build into what you’d already published, rather than extending the story from the point where you’d left off.

Michael: The thought behind doing Starstruck as a Comic Book, back in 1980-81, was that it’d come out in a sort of bi-monthly schedule, or Monthly if in a Magazine, and the story would layer easily with the readers. As it happened, that didn’t happen, and when the story first came out in Heavy Metal, the editors often gave the story arbitrary page lengths, halting the flow in what was already meant to be a challenging storytelling approach. My philosophy at the time was: let them catch up (stolen from Robin Williams)… I knew that there were folks who craved a comic book story that could keep them engaged while entertaining them, and Elaine Lee rose to that with gusto!

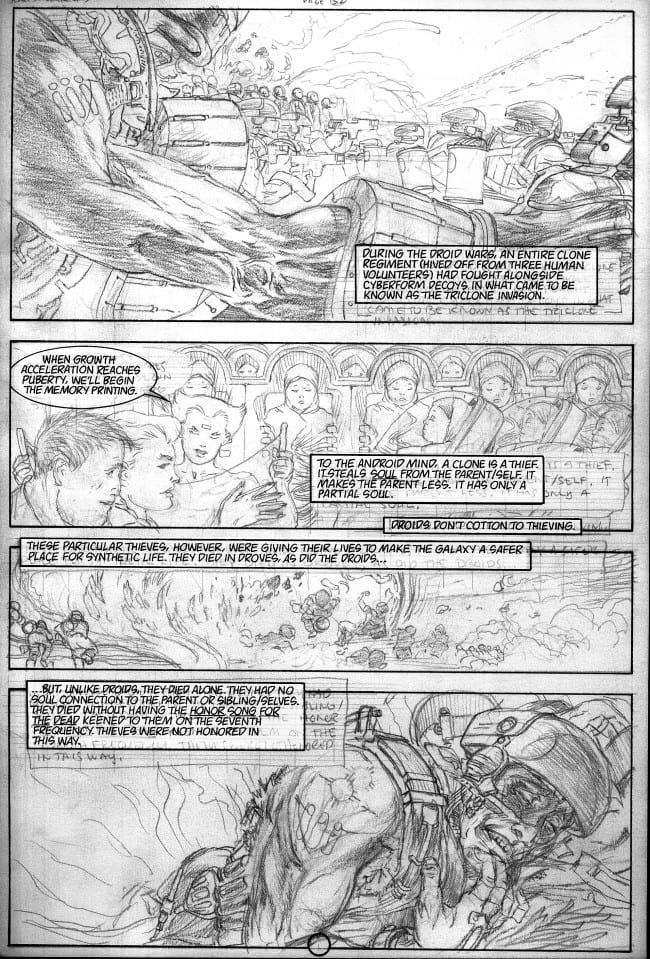

Elaine: The decision to expand the story from within was a natural one. When we first decided to do a Starstruck graphic novel, we had to decide how we wanted to do it. We knew we couldn’t do the play. It was just too “talky.” Plays are all about the dialogue. And the play detailed the confrontation between the crews of two ships that meet in space. The story was too small and not visual enough for a graphic novel, much less a comic series. But the characters in the play had each been given a monologue in which they talked about an important incident from the past. We decided to make the graphic novel a series of vignettes, based on these monologues. But, in some cases, years passed between, say, Kalif’s story and Galatia 9’s. So, there were big time jumps in the chronology. When we got the chance to do the Epic books, we started from where we’d left off and continued the story from there. We were supposed to do twelve books, but were told we were being cancelled after the first few were done. So we ended up shortening the story we had planned, so there would at least be some sort of an ending. When Dark Horse picked us up, it made sense to fill in the gaps - to let people know what certain characters had been up to, during those time jumps, and to put planned story elements back in that had been cut when we were cancelled.

Michael: When it came to expanding the stories, adding in plot lines, it turned out that my approach to my “background” characters made fitting the new material into the pacing a lot easier. Like seeing the second Back To The Future film, the expanded Starstruck was the exact same action but with a lot better omniscient viewpoint given to the reader.

TCJ: For the present edition, you’ve again revised Starstuck’s existing pages – both the storytelling and the artwork (including the expansion of each of the first 80 pages). Can you talk about what led to this revision process and how you approached it?

Elaine: We’ve gone back and forth between serialized, graphic novel and comics versions of the work, so that putting it all in one big book was a challenge. The pages were of many different dimensions and, when we put them all together, double page spreads might end up not being on facing pages. So, we had to add to the length of some pages, in some cases giving more room to existing panels, in others adding panels. We added at least one new page of art and, in a couple of places, rearranged art, adding new text. We added a couple of these rearranged pages to the IDW comic series that we decided to leave out of the Deluxe Edition. We had put them in to make the design work out, but didn’t need them in the collection. All the pages will be there on the website, however, both the pages we added to the series and those we added to the collection. There’s room for everything there!

Michael: The largest part of my work on getting the Starstruck Pages ready for publication in the IDW volume was extending about 80 of the pages by 2 and ¾ inches. Given Elaine’s tight storytelling, the pacing of each monologue and dialogue, I couldn’t just put a thin panel in between others to lengthen the pages… I had to make selected panels taller, matching the rendering I did 30 years ago… for the first 20 pages it was a technical struggle: then I hit on a technique: time consuming, but near flawless: scan the art (had been done already, of course) select which panels/panels were to be lengthened: crop the top and bottom lines off the panels in Photoshop, print same (same size as the originals) then draw on the printed paper. Scan that page at the same DPI as the Art, go into the now lengthened page template and replace the previous panel with the taller one. Draw new panel borders and on to the next!

TCJ: I’m curious to hear about what it has been like to live with and to engage creatively with the same work – and your younger selves – across three decades.

Elaine: It’s been a little strange working with Starstruck over so many years. There have been characters I’ve identified with more strongly during certain periods of my life, so that those characters were given prominence within the story. When I was coming up with characters and plot for the original play, I wrote Galatia 9 for myself to play. I was about 5’ tall and weighed maybe 95 pounds at the time, but I wanted to be the Amazon Captain, so I wrote myself one. I was a big Star Trek fan as a kid, but I had hated that last episode in which Kirk switched bodies with a woman who wanted to be a star ship captain - which meant, of course, that she was insane. Kirk’s last line was, "Her life could have been as rich as any woman's. If only... if only..." (meaning, “if only she hadn’t had any ambition beyond being a Kirk-smooching, mini-skirted yeoman”). Beyond that, as an actress, I thought it would be fun to play a character that embodied exaggerated versions of all the traits that bothered me in myself. I was flat-chested, so I gave Galatia 9 a missing breast, building the other breast into one side of the costume. I had had surgery for scoliosis, which left me with scars down my back and a slight limp, which I exaggerated on stage, by putting an ankle weight inside one boot. My costume was asymmetrical and I put a big scar over one eye and down my face. Galatia is sometimes blindly idealistic, sometimes paranoid, and she enjoys her booze; traits that I share, but more so in my youth.

By the time Michael and I started working on the Marvel graphic novel, I got into Ronnie Lee’s head. In the stories, as they were printed in Ilustracion+Comix International and Heavy Metal, there was no narration from Ronnie Lee. We added that for the Marvel graphic novel. A lot of the frustration I felt, growing up as a girl in a small southern town during the '50s and '60s, went into that character. That feeling of being meant for something better than circumstances allowed.

Then, when we started doing the Epic comics, I found that I was getting tired of all the female characters and wanted to add a strong male character to the cast. Enter Harry Palmer. He had been a side character in Galatia and Brucilla’s story, but Michael and I decided to give him his own storyline. It was lovely to spend a couple of issues walking around in Harry. He may be my very favorite character. He’s certainly the most loyal, loving and stable character in the Starstruck pantheon.

We began doing the Expanding Universe books for Dark Horse when I was the mother of a very young child. That was when we started beefing up the character of Mary Medea (AKA Glorianna of Phoebus) and I’m sure my own motherhood played into the scenes of Mary and her mother, as well as Mary with her much younger sibling, Molly (Galatia). Mary was a behind-the-scenes manipulator of much of the action, which is sort of what you become as a mother. You are no longer the main character, but you play a large role in shaping the main character. (By the way, that baby I was tending during the Dark Horse days ended up playing Rootersnoos Ferret Jimmy the Snout in the recent Starstruck audio adaptation.)

By the time we got to the IDW series and collection, I wasn’t making too many changes to the actual pages, but I wrote forwards for the series in the voice of Dwannyun of Griivarr. Dwannyun was a main character in the play, who hadn’t had much chance to breathe in the comics. We had set up a history for him that described him as a complete failure until the time of the play. So, I took him into the future, made him a historian, and had him write a history of the events in the comics, from that future perspective. So, as the character, I was writing a history of this world we had created over several decades. In doing so, I could hint at secrets that Michael and I knew, but that had never made it into the pages.

Michael: I’d “given up” on comics a few months before meeting Elaine and her sister Susan and falling into their Gravity Well… that what they were up to when met was a play, and what they wanted was a poster (then costumes, because there would be costumed characters on the poster, then Sets) it wasn’t comic books at all! I learned what a Hot Glue Gun was. I learned that Stage Clothing/Costuming wasn’t like drawing, real life or stuff for Films: it could look slapped together up close (and generally WAS slapped together) and look like a million bucks from the audience. Never having designed costumes for folks to wear, it was twice-lucky that Elaine knew Costuming and had all the necessary arcane equipment needed to make spacy-looking stuff. (Leather Punch, Rivet Setting Tools, the Hot Glue Guns and her expertise). When set design and building came into the mix, skills I’d honed as a kid (dumpster diving it’s now called) came to the fore… and NYC is a Treasure Trove of Interesting Stuff waiting to be appropriated and redefined. I’ll not go on about how finding “things” that could “look terrific from the audience” took over my waking life: Refrigerators: the inside of their doors, turned upside down and painted silver with a bunch of tacks, Legg’s Eggs and Disposable Razors hot glued in series: Voila! An entire wall of Space Stuff! I think Elaine mentioned the Hot Wheels track.. there was a kid’s bowling toy that made a terrific console and card table legs, removed from the table and set upside down along the bottom edge of the console wall became levers Brucilla and Galatia could use to pilot The Harpy.

Elaine: Writing new Starstruck material now doesn’t feel the same as it did in the beginning. In the early days, Michael and I lived Starstruck. We worked together, writing and drawing in the same room. As time went on, each of us worked on our own more. By the time of the Dark Horse series, I was a Mom and we were working separately. Now, I’m a completely different person from the girl who had the idea for the play. But the Starstruck universe is so familiar that I can put myself back in that head pretty easily. I can write it, without being as attached to it. As the pages go up on the website, I am writing new glossary entries that link to the pages. So, it goes on.

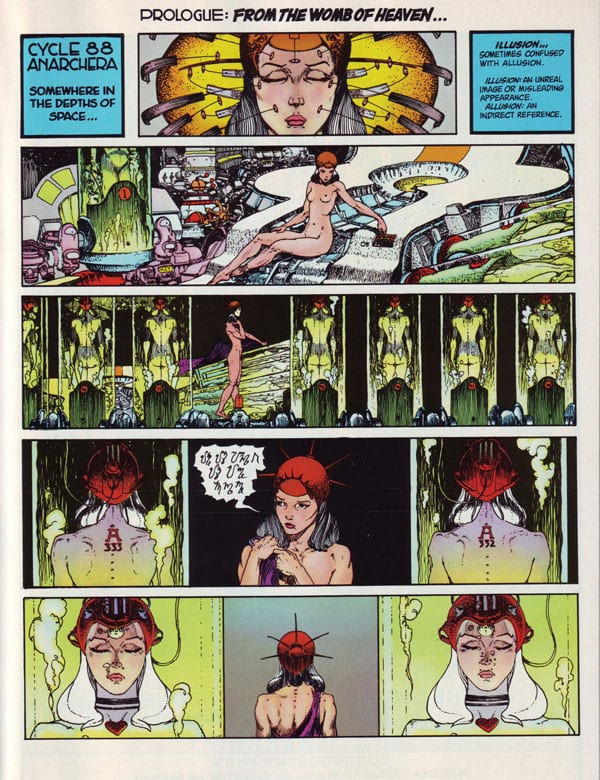

TCJ: Let’s spend some time with the first page of Starstruck, which introduces a number of narrative, structural, visual, and thematic traits of the series. Among other things, this page inaugurates Starstruck’s approach to making the reader work harder than usual to understand a comic book. For instance, there are no conventional boxes full of explanatory copy on this page or on any other page of the story.

Michael: The first page of Starstruck has always felt exactly right… it was one that adding in another panel to get the page length correct for printing almost didn’t work… still, I knew that some folks would keep that first scene in their minds as they read on and, eventually, pieces would fall together. Getting to expand the story many years later, it was like affirming to those who “felt” they knew what was happening before the expanded version that they’d been right all along.

Elaine: We weren’t really thinking of omitting or changing any comic book conventions. We were just thinking of doing a story we really liked. Hmmm… maybe we were thinking of doing a story that was fun to create. And we were as much influenced by stories from other media, like film or novels, as we were by comics. In his novel, Dune, Frank Herbert had begun his chapters with excerpts from the writings of Princess Irulan. I’m sure that was an influence, though we used the writings of many different characters to begin our Starstruck chapters. I was a big fan of movie director Robert Altman, who let his story be gradually revealed by moving you through scenes where you would pick up bits of information from the many characters in his large cast. And literary novelists, known for the dark humor of their work, like Thomas Pynchon. Joseph Heller and Kurt Vonnegut were certainly an influence. American comics were probably more of an influence on the play, than on the Starstruck comics. The play had a more straightforward story. And 50s and 60s low-budget sci-fi films and television were an influence on both.

The style of Starstruck was probably shaped by the content, as well. There were certain ideas we were interested in getting across. For instance, people lie. They are mistaken or misinformed. They may understand only part of the picture or they may not be able to see past their own agendas. We wanted a story that reflected that reality. So, you may see an episode in which one thing is happening in the narration (which might be a history, written in a later time) and another, completely different thing is being talked about in the dialogue, but when you look at the art, you see that something altogether different is happening, because neither the future historian, nor the characters living the event understand what’s really going on. Content decides style.

I remember Larry Hama telling me about some of the letters to the editor he’d gotten during his time at Marvel. One reader wrote something like, “In Conan #2, Conan says he’ll never run from a battle. Then, in issue #957, Conan runs from a battle. What gives?” That really made me laugh. So, what Michael and I are saying is: Just because Conan tells you something is true, that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s actually true. (And we might even hit Conan in the face with a giant hotdog; just to make sure he and everyone else gets the point.)

TCJ: Right out of the gate, the series announces its interest in the female body as a potentially conventional object of male desire, but in what turns out to be an unconventional plot of female empowerment. You decided to start your script with a woman hatching an elaborate political/economic power play involving mass production of sexbots. Why?

Elaine: The sexbot came first, the plot later. When coming up with characters for the play, I thought it would be fun to have a reprogrammed pleasure droid aboard the space ship, the Harpy. She would have the mind of Spock, the body of Marilyn. At the time, a lot of people in the media were writing about divisions in the women’s movement. Should women be trying to be like men, compete with men, do men’s jobs? Or should the women’s movement instead be trying to change the world, in order to make the world reflect more traditionally feminine values? The character of Brucilla the Muscle was a role reversal, a female version of every hotheaded, gung-ho, young, male space cadet in '60s sci-fi movies, or war-in-space science fiction novels. And the pleasure droid, Erotica Ann 333, was the traditionally feminine woman to the max. Erotica Ann is brilliant and almost always right, but Brucilla can’t see past her appearance and manner. Bru can’t stand Annie. Of course, the Annie 333 you see on the first page of the comic, along with her “sibling” droids and their maker, Mary Medea, is not the Annie of the play. She hasn’t begun to think independently and she hasn’t been reprogrammed to serve as a crewmember of the Harpy.

In the play, Annie has a monologue, through which she tells the story of being owned by a young Kalif Bajar. She explains that, when he realized the droids were not able to love him, he ordered that they all be melted down in a vat of acid. As she watched her sisters march, one by one, into the acid, Annie had her first independent thought. She thought, “If I stay in this line, I’ll be melted down in acid.” Annie walked away and survived, later to meet up with Galatia 9, who has her reprogrammed to serve aboard the Harpy.

As far as Mary Medea’s schemes go, I think the idea of the seductive female spy has been around for quite a while. The desirable woman who isn’t what she seems. The Annies serve as Mary’s proxies, programmed to get close to their target, then preventing the target from achieving what he might have. Because they look exactly like Mary, they also serve as cover for her. When she wants to go into a situation, she can dress like an Annie and go wherever they are. In this case, that “object of male desire” is a honey trap. He may perceive her as an object, but he is actually enthralled, her slave. Kalif’s sister throws a wrench into the works, however. By the time she’s through messing with her brother’s mind, he’s attached to the headless (thoughtless, speechless) Annie. Like many of us, men and women alike, he would rather invent a personality for his love, than deal with an actual being, even one as pliant as a pleasure droid.

Michael: Kalif gets “his” Annie back after her rebuilt head “changed” her, by echoing his father’s blowing the head off one of the droids. A telling point: the beheading is done to a completely different Anne, #72, as opposed to the original headless Anne #1. Headless, she is His Annie.

Elaine: The Annie Kalif loves is the one he imagines. As sick as this might be, it keeps him from being “guided” by Mary, through her droids. In the end, it is Ronnie who is enthralled by Mary Medea. She spends her life trying to understand and/or thwart Mary.

TCJ: Michael, in its final form, this first page is a really unorthodox, adventurous comic book page (let alone as a splash page for an entire series). It contains six panels, five of which stretch across the whole page. However, you’ve used the situation being illustrated (many identical female forms/faces) to create the illusion of more than a dozen panels on the page. And you’ve used light and dark areas to create an almost perfectly symmetrical composition.

Michael: I can’t remember my thought processes on the day I laid out the first page of Starstruck… I remember wanting to: 1) Introduce the Character. 2) visually show she was master/mistress, completely in control of the mysterious process being portrayed. 3) show there were a LOT of copies of her. 4) contrast Glorianna’s human movements against the implied mechanicalness of the androids, and 5) allude to Glorianna having a personal interest in one of the androids. Adding in the extra panel for the newest version was somewhat simpler than drawing it: Photoshop is a boon… but, although the Annies are identical, the fluid in the tanks was lowering, the bubbles rising, so there was more than just one cut, copy and paste to get the complete page. Since there were now quite a number of pages following the first page, it seemed important to add a background in the final two panels to give them a sense of belonging to the rest of the strip.

The layout of the page seemed the only way to do it: I felt it was given me in the subject matter. I owe the tracking camera approach to Goseki Kojima, the artist of Lone Wolf and Cub (and he owes that technique to Kurosawa, I’m sure!) That the first page was to be a symbolic opening, immediately followed by the Bajar Throne Room Sequence, allowed me to be more structured with it: by making it appear iconic, it contrasted nicely to the everyday madness going on in the following story.

TCJ: You had drifted away from comics before Starstruck, and you have never been particularly committed to extended comic book narratives. Can you speak to how you re-engaged long-form sequential art with Starstruck, and how your compositional approach to non-sequential art (comic book splash pages and covers, book covers and illustrations, posters, etc.) influenced your page compositions?

Michael: My drifting away from comics was more like me trying to swim away from a whirlpool… at the time I met Elaine and Susan I felt my work had become very stale. And I was also not a very good Worker. The major effect Starstruck had on me was to give me a reason to draw comics: the unique approach to the story intrigued, getting to layer the visuals in service of creating a sense of place for the characters was fulfilling, and the immediate feedback from Elaine on my choices made staying with the art easier than anything I’d done since Carson of Venus (of course, Carson was mostly a 5 page monthly strip… nothing compared with the huge amount of pages to eventuate from starting and committing to Starstruck)

I’m not certain my Cover Work for other comics, nor my illustration work, gave anything major to Starstruck beyond that my ability to draw had improved through the doing. The pacing of Starstruck, the sweep, the set-ups needed to give room for developing sub-plots and surprises gave me challenge after challenge: rising to those challenges made me use everything I’d ever seen, thought, read or heard of. Ideas sparked more Ideas, problems were worked out on the spot. Having to please only myself, and the writer sitting on the couch behind me, made the art grow into the epic it has become. Had I been handed a finished, 300 page script of Starstruck at the time of starting, alone at my drawing board, I shudder to think of what I’d have done.

TCJ: Lee Moyer’s new coloring is a dramatic departure from previous treatments of Starstruck. It is also highly illustrative in its own right. Did you actively collaborate with Moyer on this dimension of the new edition? How did he become the colorist in the first place?

Elaine: Lee Moyer has been involved with Starstruck, since way before he did the color for this edition. When he was a kid, still living at home, he saw Starstruck in Heavy Metal magazine and wrote Michael a letter saying, “If there’s anything I can ever do…” Later, Michael would meet the young Mr. Moyer, when they worked together on a video for by the Alan Parsons Project song, “Don’t Answer Me.” When the Marvel/Epic comics were coming out, Lee sent us examples of android Stark Verse that he and his friends had been writing for each other. Then, when we were doing the Expanding Universe books for Dark Horse, Lee wrote the “what happened in the last issue” pieces for us, signing them as Rootersnoos Ferret, Lee Moyer. During the years that Starstruck was stuck in a holding pattern, Lee sent us three beautifully painted pages. These were pages that had never been colored, from the black and white Dark Horse books. His note said, “If you ever intend to do a digitally painted version…?” By the time we got to the IDW series, it only made sense to ask Lee to do the color. Besides being an incredible artist in his own right, he knows Starstruck inside and out. He probably knows it better than Michael and I do!

Michael: As much as I’d like to take Big Credit for Lee Moyer’s painting of the Starstruck Pages, I can in truth only claim my contribution was in giving color notes to the Spanish Artists who did the airbrush color for the pages that appeared in Heavy Metal Magazine back in ’82 and eventually in the Marvel Graphic Novel from Epic. Basically my contribution was character costume colors. All the rest is Lee! Though I gave out with a few, “Could That Be Green?” and “Maybe That Should Glow?” comments, my involvement was as a fan: I got to go WOOOOOOOO! And as any creative person can attest: if something allows one to go WOOOOOOO! over one’s own art, it is a blessing!

Oh: I DID tell Lee “Remember, there are over 200 pages of this highly detailed art: Don’t Kill Yourself with the First Pages and then have to match them for the entire 200+” … of course, he ignored me, to our benefit. As Elaine points out: Lee knew the story backward and forward: I knew he’d know what to accentuate and what to let alone… even better than me, sometimes. It was a rare day when Lee would need to know what it was he was looking at in my panels, though I’ve a suspicion there were more times he crossed his fingers and dived in (to terrific results) than he’ll ever let on. AND: Lee is FAST!!!! Once or twice I sent him line art for the covers, intending to send color notes in the following email, only to have a note arrive from Lee with the finished color cover attached. I’m still agog!

Elaine: I worked very closely with Lee on the “extras” pages for the IDW comics and Deluxe Edition. Michael did new art for many of these pages, but Lee also did some of the art, a few of the mission patches, the Space Brigade poster, and the brochure for the Garuda – the ship that eventually becomes the Harpy. He repurposed and expanded existing art, for the Personalities of AnarchEra cards, as well as posters for the Ramscoop Lounge and the Aguacade. Lee did the design for the inside cover pages. In some cases I would send Lee text and he would design the page, in others we would chat, he would do the page, leaving room for text. Lee and I we worked together on the Book Design for the Deluxe Edition. Besides being incredibly talented, Lee is the consummate professional and very entertaining, and I would work with him again in a heartbeat.

TCJ: Jean Moebius passed away on March 10, 2012. What was his influence on Starstruck?

Elaine: Quite simply, there would have been no Starstruck, if there had been no Moebius. As a kid, I had been a voracious reader of comics, but had given them up as I entered my teen years. Then, in my early twenties, I discovered Heavy Metal and the European comics artists. Moebius was my favorite. At the time, I was living in Manhattan and working as an actress, but was also taking a playwriting class at The New School… a really bad playwriting class! I was given an assignment to write a scene about two people fighting over an object. The two women in my scene were the prototypes for Galatia 9 and her sister Verloona and they were fighting over a box, contents undisclosed. My ex-husband read the scene and said, “This is just like something from Heavy Metal!” I dropped the class, but kept working on the idea.

Now, I’ll tell a story at Mr. Kaluta’s expense. While working on Starstruck, Michael went through a bad patch of artist’s block. Every time I dropped in on him, he was either sleeping or reading and I was starting to get cranky about it. I asked him what the heck was going on. Michael’s answer? “I’ve started to worry too much about whether or not Moebius will like it.”

So, from my point of view, Moebius was both the inspiration for, and almost the end of Starstruck!

Michael: I met Moebius as Jean Giraud when Jean-Pierre Dionnet came over to the USA with a gang of Top Flight French Comic Strip Artists (including Jean-Claude Forest: Barbarella, and the astounding Philippe Druillet). JP Dionnet became our Translator, being able to speak both languages, and brother did he hop from one to another. The first meeting was in the coffee room at the DC Comics/Independent News offices: a smallish room, now full of Frenchmen and Americans, all Comic Book Artists, all wanting to communicate to each other… On our side (if there were sides) there was Neal Adams, Alan Weiss, Berni Wrightson, etc. I can still see Howard Chaykin over my shoulder waving his hand toward Dionnet to come and help his conversation, while I had a hand on Dionnet’s chest, holding him in check until he could speak for me. We all traded drawings.

The Art of Moebius is the benchmark for Brilliant Comic Book Drawing, as well as being a high water mark in the design and characterization areas. I knew when I began Starstruck whatever I’d absorbed reading and studying his work would come out in anything I did that was “sci-fi”, but I did make it a rule not to look at his art while drawing: Moebius had so many elegant solutions to artistic and story-telling hurdles that his work would overwhelm anyone not careful to channel his being while staying clear of copying his results.

One of my quirks: when I draw a subject, my art tends to reflect that subject: hence one not studied in my work would think one of my Tolkien Calendar Illustrations done by someone entirely different than the artist responsible for Starstruck. Because Elaine’s Starstruck story covered (on purpose, note) so many different people, places, things and situations, my work, though uniform in the overall presentation, adjusted to different scenes by, say, softening when we are on New Wyoming (the Arizona Highways World), or hardening when Harry Palmer walks the Voidfront. Of course, the signature of an Elaine Lee Story is: you never get just what’s expected, so, in the Hardware-Driven Brucilla Story, Moebius-like machinery gets to meld with Spin and Marty high jinx, and the art followed suit. When discussing the various stories during the working process, it was often a reference shared from a 50’s TV show, commercial, joke from Boys Life or “something I heard once” that’d imbue an otherwise mundane artifact or scenario with the feeling “Hey, I’ve SEEN that… but where???”

Luckily, the fun we had doing it translated into fun for everyone!