In the interest of full disclosure, a couple of personal notes, before the obituary:

Harlan Ellison made enemies. He made them with gleeful abandon. He also made loyal friends, fans and acolytes, but the only person who comes to mind who was capable of making enemies as blithely as Ellison did is Gary Groth. Ellison and the TCJ publisher were friends and then they were, almost inevitably, enemies. Not just winking frenemies, but mutually contemptuous, financial-life-threatening legal opponents. Now the time has come for one enemy-maker to publish the obituary of its enemy-making enemy. So it’s understandable if readers may expect a less than reverential remembrance here.

Groth’s extraordinary, industry-jarring interview with Ellison was published in 1979 in TCJ #53, the first issue of The Comics Journal that I ever purchased. It was a meeting of iconoclasts, a thrilling display of discerning, dyspeptic honesty, and possibly their finest moment together. It also led to the lawsuit filed against Ellison and Groth by DC writer Michael Fleisher, who took exception to being called “bugfuck crazy” by Ellison. The interview made me a fan of both Ellison and Groth even as it planted the seeds of what would become a permanent rift between the two.

My first job in the comics media was as a writer/editor on Comics Buyer’s Guide. When I horrified many of CBG’s collector-readers by casually mentioning my willingness to roll a comic book up and stick it in my pants pocket, Ellison wrote in to defend me — even though his own comics collection was stored in a temperature-controlled vault. Thereafter, he would occasionally send clippings for my column and notes of support.

In short, however exalted a creator he may have been, however much his merciless perfectionism and mercurial ego may have bedeviled industry suits and colleagues, however much he may have frustrated, exhilarated, disappointed, delighted, disgusted or shocked friends, ex-friends, fans and haters, my memories are entirely of Harlan Ellison the Nice Guy.

Science fiction’s enfant terrible, Harlan Ellison, passed away June 27 at the age of 84. At the request of his wife, Susan, close friend Christine Valada, widow of comics writer Len Wein, announced that Ellison had died in his sleep via Twitter. The once passionate, energetic author had been in ill health for some time, suffering a stroke in 2014 that paralyzed his right side.

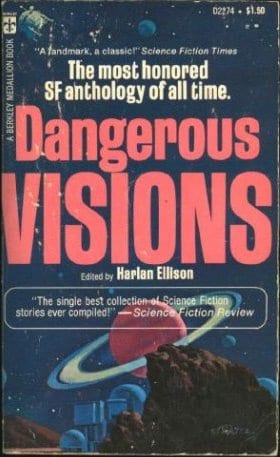

Ellison is known primarily for his work in science fiction (or speculative fiction, as he preferred to call it), including the Star Trek episode “The City on the Edge of Forever”, the novella and movie A Boy and His Dog, and his editing of two Dangerous Visions anthologies. But though he scarcely wrote any comics stories, he has long been embraced by the comics community as a kindred spirit, a challenge to the hidebound, compromised conventions of traditional entertainment. Comics fans identified with his attitude, his wide knowledge of comics mythology, and his strongly held opinions, perhaps because when it came to comics he was more fan than pro. He loved comics and he was iconoclastic enough to liberate the form from its cultural ghetto, granting comics the same respect and high standards he accorded more mainstream literature.

Ellison is known primarily for his work in science fiction (or speculative fiction, as he preferred to call it), including the Star Trek episode “The City on the Edge of Forever”, the novella and movie A Boy and His Dog, and his editing of two Dangerous Visions anthologies. But though he scarcely wrote any comics stories, he has long been embraced by the comics community as a kindred spirit, a challenge to the hidebound, compromised conventions of traditional entertainment. Comics fans identified with his attitude, his wide knowledge of comics mythology, and his strongly held opinions, perhaps because when it came to comics he was more fan than pro. He loved comics and he was iconoclastic enough to liberate the form from its cultural ghetto, granting comics the same respect and high standards he accorded more mainstream literature.

If one were to draw a graph of Ellison’s creative career, it would appear as a rapidly ascending line in the early 1950s, bulging heavenward throughout the following densely productive couple of decades until around 1975 (roughly from Ellison’s early 20s to his mid 40s), when it would seem to fall off a cliff. Beginning around 1975, Ellison all but ceased to be a working writer, becoming instead a re-packager, an introducer, a creative consultant, a master of ceremonies, a cameo voice in video games and animated TV shows, a guest of honor, a website commenter, and a lawsuit filer. The first half of his career alone, however, was fertile enough to leave most other professional biographies green with envy. Ellison had written so many stories, novels, screenplays, teleplays, movie and television reviews and essays, won so many awards and assaulted so many publishers, critics, professors and Hollywood producers in such a short period of time, that an early burnout would seem to have been inevitable. His persona — the young, vital, aesthetically righteous punk who did not hesitate to kick the ass of the stodgy, greedy entertainment establishment — was so indelible, that it was hard to imagine Harlan Ellison as an old man.

A major obstacle to any biographer who wants to be true and thorough is Ellison’s natural storyteller’s tendency to self-mythologize. There are stories galore about Ellison’s life and career, most told with great relish by himself, but often the details seem just a little too perfect to be entirely factual. For example, his remembrance of escaping through his bedroom window on his seventh birthday to run through town in order to catch a showing of the Fleischer Brothers animated feature Mr. Bug Goes to Town. A remarkably beguiling story in itself, but in Ellison’s telling it doesn’t stop there: He was found by a flashlight-wielding usher and returned to his bed, only to climb out his window, run back to the theater and resume watching the movie until recaptured and brought home not once but twice more. The third and final time, he was stapled to his bed by his pajamas … or so the story goes. Later, it was pointed out that the movie had not been released until the following year and, in any case, would not have been showing at that theater on Ellison’s birthday.

A major obstacle to any biographer who wants to be true and thorough is Ellison’s natural storyteller’s tendency to self-mythologize. There are stories galore about Ellison’s life and career, most told with great relish by himself, but often the details seem just a little too perfect to be entirely factual. For example, his remembrance of escaping through his bedroom window on his seventh birthday to run through town in order to catch a showing of the Fleischer Brothers animated feature Mr. Bug Goes to Town. A remarkably beguiling story in itself, but in Ellison’s telling it doesn’t stop there: He was found by a flashlight-wielding usher and returned to his bed, only to climb out his window, run back to the theater and resume watching the movie until recaptured and brought home not once but twice more. The third and final time, he was stapled to his bed by his pajamas … or so the story goes. Later, it was pointed out that the movie had not been released until the following year and, in any case, would not have been showing at that theater on Ellison’s birthday.

Harlan Jay Ellison was born May 27, 1934 in Cleveland, Ohio. His parents were Louis, a dentist and jeweler, and Serita, a thrift-store clerk. His short stature and Jewish heritage made young Ellison a target for anti-Semitic bullies at Lathrop Elementary and East High School and he was regularly roughed up. Speaking in a 2008 documentary, Harlan Ellison: Dreams with Sharp Teeth, Ellison said, “When you’ve been made an outsider, you are always angry.”

It’s not hard to draw a line from this troubled past to certain themes in his life and work: 1) his urgent assertion of masculinity, bragging machismo and quickness to resolve conflicts via physical confrontation, and 2) his sensitivity to the alienation and oppression of minorities, which underlies much of his fiction and critical writing. It may also have led to a restless eagerness to strike out on his own at an early age. He was reportedly a frequent runaway during his childhood, and by the time he turned 18, as he told it, he had accumulated an assortment of odd jobs on his resume, including cab driver, tuna fisherman, crop picker, short-order cook, door-to-door salesman, lithographer, mobster’s assistant and actor at the Cleveland Play House. He was expelled from Ohio State University in his sophomore year after punching a writing teacher who had disparaged his work.

Ellison hit the science-fiction field running and quickly gained a reputation as an aesthetically motivated wunderkind who took his work seriously and would not tolerate the slightest compromise even when it came to writing for pulpy men’s magazines or schlocky TV shows. Except for a couple of stories for the Cleveland News, his first professional sale may have been a comics story: William Gaines and Al Feldstein had solicited story ideas for EC’s line of science fiction and horror titles, and Ellison submitted a plot that was adapted by Feldstein and Al Williamson and published in Weird Science-Fantasy #24 (1954) as “Upheaval!” The story was later recycled in prose form by Ellison under the title “Mealtime.”

In 1955, Ellison followed “Upheaval!” to New York and immersed himself in a street gang as research for a series of stories that were sold to men’s magazines like Gent and Rogue and collected in 1959 as Sex Gang under the pen name Paul Merchant. Between 1955 and 1957, he sold more than 100 stories, mostly to men’s magazines and science-fiction pulps. He was drafted into the Army in 1957, but produced his first novel, Web of the City (published in 1958), while undergoing military training.

A major career breakthrough came when Ellison’s 1961 collection Gentleman Junkie and Other Stories of the Hung-Up Generation caught the eye of literary legend Dorothy Parker, who gave it a positive review in Esquire. Bolstered by this recognition, Ellison left his editing job at Rogue in 1962 and moved to California, where he began a combative relationship with Hollywood.

Things started relatively slowly for him on the West Coast. The first year, he sold only a plot for a Route 66 episode and a half-hour script for Riptide, but he became part of the writing team for the Gene Barry series Burke’s Law in 1963 and saw four of his scripts produced. He went on to write episodes of The Outer Limits, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, and The Alfred Hitchcock Hour in 1964. In 1966, he was hired to write his first feature film. It was a Stephen Boyd-starring fiasco called The Oscar, which still appears on many worst-film lists and effectively nipped his movie-writing career in the bud. His original screenplay for Valley of the Dolls fared no better, and his name was removed from the credits. Just how loathsome he found Hollywood’s Philistinism became clear in a column of television criticism he wrote for The Los Angeles Free Press from late 1968 to early 1970. Collected in two volumes called The Glass Teat and The Other Glass Teat, the column was a virtuoso expression of aesthetic and political disgust at the pabulum regularly consumed by mass audiences.

Things started relatively slowly for him on the West Coast. The first year, he sold only a plot for a Route 66 episode and a half-hour script for Riptide, but he became part of the writing team for the Gene Barry series Burke’s Law in 1963 and saw four of his scripts produced. He went on to write episodes of The Outer Limits, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, and The Alfred Hitchcock Hour in 1964. In 1966, he was hired to write his first feature film. It was a Stephen Boyd-starring fiasco called The Oscar, which still appears on many worst-film lists and effectively nipped his movie-writing career in the bud. His original screenplay for Valley of the Dolls fared no better, and his name was removed from the credits. Just how loathsome he found Hollywood’s Philistinism became clear in a column of television criticism he wrote for The Los Angeles Free Press from late 1968 to early 1970. Collected in two volumes called The Glass Teat and The Other Glass Teat, the column was a virtuoso expression of aesthetic and political disgust at the pabulum regularly consumed by mass audiences.

He continued to write well-received television scripts including two for The Man from U.N.C.LE. (1966 and 1967), a Jack the Ripper-themed Cimarron Strip episode (1968), and even a Flying Nun episode (1968), but he was increasingly impatient with the manipulations his scripts underwent at the hands of commercial-minded producers. When a script was altered enough that he preferred to disown it, he insisted that the writing credit go to “Cordwainer Bird,” a brand of shame similar to the Allan Smithee credit used by dissatisfied film directors. Assigned to write an episode of The Young Lawyers, Ellison serialized the script in his Freep column and chronicled his progression from pride to contempt at the studio’s sterilization of his work. By the end of Ellison’s television-writing years, Cordwainer Bird’s list of credits had grown at least as fast as Harlan Ellison’s and included the Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea episode, the entire Starlost series (1973), two episodes of the cable series The Hunger (1998), and the Flying Nun episode. (During a Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea production meeting, Ellison leapt across the conference table, his fist colliding with producer Irwin Allen.)

Even Ellison’s crowning television achievement, Star Trek’s “The City on the Edge of Forever” (1967) which won a Writer’s Guild Award and a Hugo Award, was not sufficiently faithful to his script, and series creator Gene Roddenberry’s refusal to apply the Cordwainer Bird credit soured his relationship with Ellison.

Ellison had wanted to use his television writing to decry contemporary social ills and he often tried to address issues such as racism, the Vietnam war, drugs, anti-Semitism, gun violence and political corruption in his work. He told of joining Martin Luther King’s civil-rights march from Selma to Montgomery in 1965. While a guest of honor at the 1978 World Science Fiction Convention in Phoenix, Ariz., Ellison led a protest against the state’s failure to endorse the Equal Rights Amendment. In later years, he persuaded DC to remove BB-gun ads from its comics. When a publisher violated the author’s contract by allowing cigarette ads to be inserted in one of Ellison’s books, Ellison mailed him 213 bricks and a dead gopher.

In 1975, Ellison’s story “A Boy and His Dog” was adapted into a feature film directed by L.Q. Jones and starring Don Johnson and Jason Robards. A post-apocalyptic parable about the precariousness of boyhood innocence and coming of age in a world of Republican adults, it gradually gained a cult following.

By this point, Ellison had amassed an impressive body of fiction and nonfiction, including 14 collections of short stories, many of which had been showered with Hugo Awards and other honors. The most notable were Deathbird Stories (1975), I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream (1967), The Beast that Shouted Love at the Heart of the World (1969) and Paingod and Other Delusions (1965). In addition to the 1958 Web of the City, he had written a novel called Rockabilly (and later Spider Kiss) in 1961. Also published in 1961: a collection of essays about his experiences with a New York street gang called Memos from Purgatory, one of which was adapted into a teleplay for The Alfred Hitchcock Hour.

By this point, Ellison had amassed an impressive body of fiction and nonfiction, including 14 collections of short stories, many of which had been showered with Hugo Awards and other honors. The most notable were Deathbird Stories (1975), I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream (1967), The Beast that Shouted Love at the Heart of the World (1969) and Paingod and Other Delusions (1965). In addition to the 1958 Web of the City, he had written a novel called Rockabilly (and later Spider Kiss) in 1961. Also published in 1961: a collection of essays about his experiences with a New York street gang called Memos from Purgatory, one of which was adapted into a teleplay for The Alfred Hitchcock Hour.

In what may have been a greater contribution to the science-fiction field than any of his stories, Ellison edited a 1967 anthology of stories called Dangerous Visions, which captured and embodied the writers and sensibilities that made up the genre’s new wave. It was a seminal book and was followed in 1972 by a second anthology, Again, Dangerous Visions.

And then the cliff. Which is a bit of an exaggeration, since Ellison’s output after 1975 would have been sufficiently respectable from most other writers. But compared to the continuous flow of fiction in the first half of his career, his later years seem like a half-hearted trickle. He continued to produce occasional collections of short stories (notably 1980's Shatterday), but they met diminishing returns on the awards circuit and the ratio of new, original stories to recycled ones began to favor the reprints. Harlan Ellison’s Watching, published in 1989, was a strong collection of acerbic film criticism, but consisted primarily of pieces written and originally published in the 1960s and 1970s. Most controversially, a third Ellison-edited anthology, The Last Dangerous Visions, was scheduled for publication in 1973 but never appeared, despite assurances on the part of Ellison, who had collected stories from at least 150 authors. In 1994, Fantagraphics published The Book on the Edge of Forever, in which writer Christopher Priest documented Ellison’s obfuscations and false promises related to the phantom Dangerous Visions volume. Eventually the book’s contributors began to die off without ever seeing their submissions in print.

Ellison can no longer tell us the reasons he sat on the final Dangerous Visions book for the last 45 years of his life or why his own writing began to dry up. Maybe after decades of frenzied inspiration, he simply ran out of things to say. Maybe he became distracted by the many accessory obligations of being a celebrity author — the public appearances, the endorsements, the controversial feuds. Certainly, he devoted a great deal of time and energy to litigation. In 1980, Ellison won a $337,000 judgment against ABC and Paramount for copyright infringement. In 1984, he threatened to sue the makers of the Terminator film for allegedly stealing the basic concept and opening sequence of his “Soldier” script for The Outer Limits. The dispute was settled out of court by payment of compensation to Ellison and the addition of an “acknowledgement” of Ellison’s work to the film’s credits. In 2006, Ellison sued Fantagraphics for defamation, claiming to have been damaged by remarks made on the Fantagraphics website. The suit was dropped after Fantagraphics agreed to remove the offending statements. In 2009, he sued CBS Paramount Television for a share in merchandising profits from the “City on the Edge of Forever” episode he had disavowed. An undisclosed settlement was reached. He regularly went after anyone who posted his writings on the Web without his permission, even filing suit against AOL in 2000 for allowing such posts to happen. An undisclosed settlement was reached with AOL.

He may have been tired, after living up to his prolific, contentious, seductive persona for so long. Ellison was short and carried a chip on his shoulder, but he was also handsome and famous, a combination that may have added a degree of volatility to his relationships with women, if one can believe the stories. He was, as they say, hard-living and hard-loving, and he could be both charming and cruelly un-charming. Between 1956 and 1976, he went through four wives before marrying Susan Toth in 1986. That partnership lasted the rest of his life. But he was still capable, while onstage at the 2006 Hugo Awards ceremony, of grabbing author Connie Willis’ breast and detonating a divisive controversy among fans.

Maybe he came to feel that his visions were not that dangerous any more. Former president of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America John Scalzi wrote in the June 28 Los Angeles Times about Ellison, in ill health, breaking down during a 2011 phone call and expressing doubts about whether his writing still mattered to readers. Creeping fear of irrelevance must have been a bitter pill to swallow for a man who had made a name for himself in speculative fiction as an angry young harbinger of the old sf’s new wave.

We have rushed through Ellison’s productive years here. Episodes from a life lived in a hurried Tasmanian Devil blur, they were too full of incidents and accomplishments to be adequately reported by a site focused on comics, a field where he did little more than dabble. But having arrived at the relatively fallow and unfocused years of Ellison’s final decades, we will linger just a little bit longer than most Ellison obituaries. Because even dormant, even ghostly, Ellison was never less than a powerful presence, and that presence continues to loom as large as ever over the fandom he had inspired.

He was born in advance of the boomer tide, but in a sense, Ellison was the voice — or a voice — of that generation, especially in his embrace of perpetual adolescence. Even his hyperbolic writing style, a cross between the fury of a Hunter Thompson and the winking pop excesses of a Stephen King, fit comfortably into the era. A victim of the prejudices of the 1940s and ’50s, a military vet, a politically and sexually awakened and enraged young man of the 1960s, a cynic of the 1970s, his life was our life — and he spoke to no one more clearly than that generation’s sf and comics readers.

A visit to the Grand Comics Database will turn up numerous writer entries for Ellison, but a closer look reveals that almost all are adaptations by comics creators of Ellison’s prose stories. “Upheaval!” in Weird Science-Fantasy was a rare case of a story initially written and proposed by Ellison for the comics medium. “Rock God” published in Creepy #32 in 1970, was also instigated by Ellison, who offered to write a story around the next Warren cover painting by Frank Frazetta. Artist Neal Adams adapted Ellison’s rough script into a 13-page comics story. The plot was a variation on an Ellison prose story. Adams also adapted Ellison’s Twilight Zone episode “Crazy as a Soup Sandwich” for the first issue of Now’s Twilight Zone comic book (1991). The 15-page Batman story “The Night of Thanks But No Thanks” was ostensibly written by Ellison for Detective Comics #567 (1986), but editor Len Wein and artist Gene Colan were probably heavily involved in adapting the story to comics form. “N.I.M.B.Y.” in The Shadow #2 (2010) was a 10-page collaboration between Ellison and artist Kyle Baker. Ellison also provided plots for titles such as Marvel’s The Avengers, The Hulk, and Daredevil. In 1995, Dark Horse published a series of Ellison adaptations in Harlan Ellison’s Dream Corridor, with an introduction to each story provided by Ellison. Beyond comics adaptations and collaborations, Ellison and his work were often referenced by Marvel writer Roy Thomas and other comics creators. Even if Ellison never wrote a single word of a proper comics script, his attitude, style, humor and imagination infiltrated a generation of comics creators.

A visit to the Grand Comics Database will turn up numerous writer entries for Ellison, but a closer look reveals that almost all are adaptations by comics creators of Ellison’s prose stories. “Upheaval!” in Weird Science-Fantasy was a rare case of a story initially written and proposed by Ellison for the comics medium. “Rock God” published in Creepy #32 in 1970, was also instigated by Ellison, who offered to write a story around the next Warren cover painting by Frank Frazetta. Artist Neal Adams adapted Ellison’s rough script into a 13-page comics story. The plot was a variation on an Ellison prose story. Adams also adapted Ellison’s Twilight Zone episode “Crazy as a Soup Sandwich” for the first issue of Now’s Twilight Zone comic book (1991). The 15-page Batman story “The Night of Thanks But No Thanks” was ostensibly written by Ellison for Detective Comics #567 (1986), but editor Len Wein and artist Gene Colan were probably heavily involved in adapting the story to comics form. “N.I.M.B.Y.” in The Shadow #2 (2010) was a 10-page collaboration between Ellison and artist Kyle Baker. Ellison also provided plots for titles such as Marvel’s The Avengers, The Hulk, and Daredevil. In 1995, Dark Horse published a series of Ellison adaptations in Harlan Ellison’s Dream Corridor, with an introduction to each story provided by Ellison. Beyond comics adaptations and collaborations, Ellison and his work were often referenced by Marvel writer Roy Thomas and other comics creators. Even if Ellison never wrote a single word of a proper comics script, his attitude, style, humor and imagination infiltrated a generation of comics creators.

His impact — sometimes energizing, sometimes destructive — was so great that the victims of his legal, physical, and verbal attacks formed a commiserating club called Enemies of Ellison, even distributing a newsletter. In response, his loyal disciples formed a club of their own — Friends of Ellison — to better spread the gospel of Harlan. A line was drawn and there were real differences, but also, as with Ellison and Groth, there were was a striking resemblance.

Whether he was provoking them, intriguing them, insulting them or punching them in the face, comics-reading boomers, enemy and friend alike, recognized that Ellison had been tailor-made to be their kind of scolding antihero. Ellison may have experienced that bond with his public as a mutual choke-hoId. In his introduction to the 1974 collection Approaching Oblivion, Ellison wrote what might as well have been his still-angry parting words: “I’m stuck on this spinning place with you, and I don’t want to go, and you’ve killed me, and I resent it, and the best I can do is tell my little tomorrow stores and keep laughing as the whirlwind whips the dirt in the playground at Lathrop grade school into an ominous dust-devil.”

Ellison is survived by his wife Susan.