————————

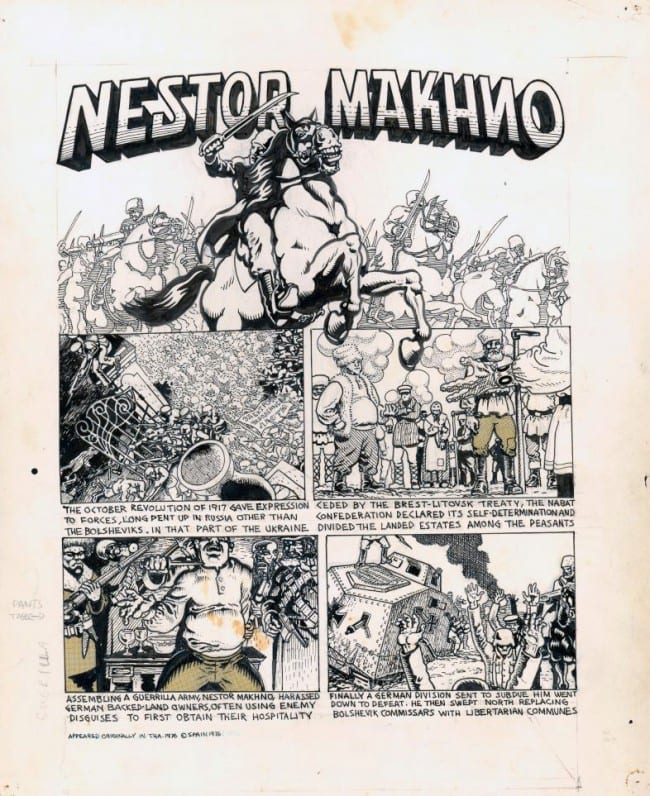

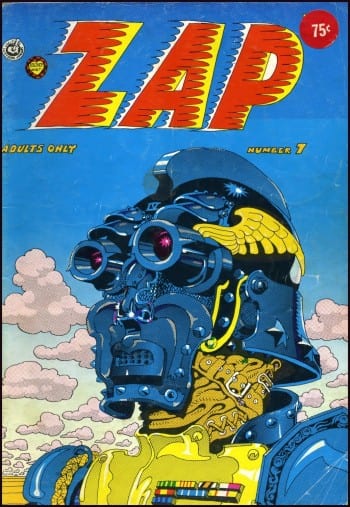

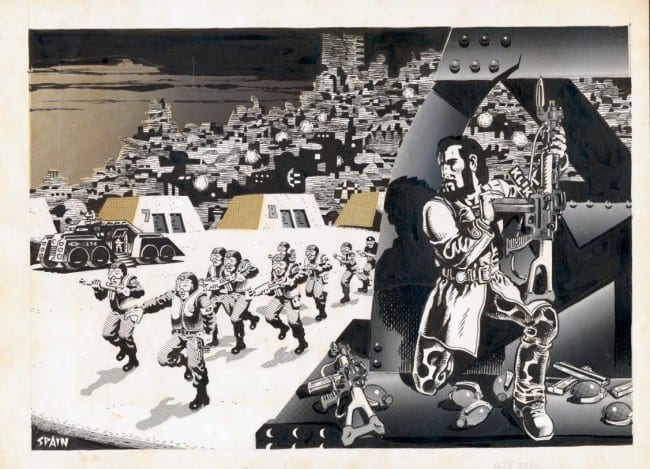

If you are lucky, a few exciting things will happen in your life that don't kill off the species. ZAP comics, which, as you know, filtered out of San Francisco in the late '60s, was one of those things--a thing one was hoping for in the void. An unprecedented (MAD didn't have dicks, vaginas, amputations, and LSD) phenomenon of defiance, audacity, pornography, bad advice, good advice, information, transport forecasts, historical ravings, a passle of approaches to cross-hatching and stylized image-making, steady or fractured or nonexistent narrative, interlocking drug-fueled collaborations, dazzling colors and shapes, references and synthesized oddments you had already been tracking like rabbit runs in the field out back. A rabbit hidey hole cubed. The few artists represented in ZAP fit like unlikely puzzle pieces somehow. It was a nitro fueled brew served in an electric phosphene hideout.

I had seen and followed Crumb from greeting cards, Williams from hot rod mags, Shelton from Wonder Wart Hog, Rick Griffin from surfing magazines, Moscoso recently from psychedelic posters, Wilson was new to me and a shocker and I had seen SPAIN's TRASHMAN in a paperback collection with Bode and Shelton. Here they were all jammed into the same projectile!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! How could this be? Jackpot.

I had seen and followed Crumb from greeting cards, Williams from hot rod mags, Shelton from Wonder Wart Hog, Rick Griffin from surfing magazines, Moscoso recently from psychedelic posters, Wilson was new to me and a shocker and I had seen SPAIN's TRASHMAN in a paperback collection with Bode and Shelton. Here they were all jammed into the same projectile!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! How could this be? Jackpot.

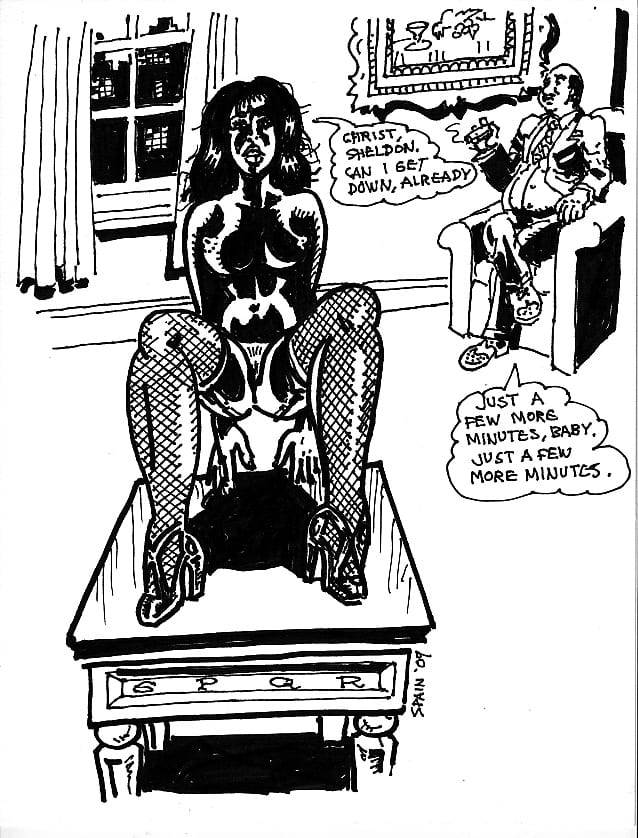

SPAIN looked to be exploring edgy scenes and choosing to do bad things and hang out with violent sociopathic folk in his comics and past at least--people that did BAAAAADD things!!! And also he was some kind of ultra left revolutionary--a bit intimidating. I was trying to be good. SPAIN was marching into bars breaking bottles over bozos. His style was Kirby-like but really only Spain-like. The other guys in ZAP were more anal. SPAIN's style was anal and precise. Yet the other guy's were even crazier than SPAIN. They made the motorcycle gang member into 'the nice one' with their tight anal approaches to putting it to the man. The other guys finished their stuff right out to the edge or the nth degree, and one got the feeling, true or not, that SPAIN might be hatching knit hose onto a hard calf or a hard center shadow onto a breast when he would drop the pen, get up, go outside, go down to the garage, grab a brew out of the fridge, get on a hawg and fuck the comics blast off down to Berdoo then come back four days later after cracking a few heads and get back to it the shadow. This is a fan's concoction--babble.

I only talked to SPAIN a few few times and he was a gentleman and solid SPAIN. The SPAIN I was hoping to meet. Courageous good people go to good places. SPAIN's art will keep making a ripple going on out.

————————

I met Spain at some comics-related event or another back in the late '80s. He was a great admirer of my brothers' work and always was encouraging me to do more stuff.

We found that we lived a couple of blocks away from each other in San Francisco and he asked me if I knew anything about cars. I told him I worked on my own vehicles some. He owned one of the most gigantic Buicks from the fifties I'd ever seen. I failed to get it going.

We became good buds after that. He and his terrific wife Susan were fairly frequent guests at each others houses for barbeques and stuff.

He gave me and my wife an original Trashman page for our wedding that I treasure. He was very generous and I loved to go to his place where he would show me all sorts of things he was working on, comics, paintings (a really cool painting of an Aztec warrior battle still sticks in my mind), and all the amazing stuff he did for movies and things.

We would often discuss history of all kinds, both of us being history buffs and fans of EC stuff like Two-Fisted Tales and such.

The last time we were together was at The Latino Comics Expo at the Cartoon Art Museum in SF. I had moved out of our old neighborhood and we only saw each other at different cons. We were being interviewed together and were asked what our dream project was and we both came up with a new Two-Fisted Tales type book that we both had talked about for years. I am glad to keep that happy memory.

The guy was a giant of a talent, and to paraphrase Maynard G. Krebs, "A real human being."

————————

I grew up with my Dad being into Underground comics. He's into Gilbert Shelton's Furry Freak Brothers, S. Clay Wilson's Captain Pissgums and Trashman by Spain Rodriguez. He told me a story once about a friend of his taking him to meet Spain and them waiting outside of Spain's apartment for hours and him never showing up. As uneventful as it sounds it was my Dad's brush with underground comics.

Years later I got my first short comic published in Donna Barr's Ersatz Peach anthology and Spain was in there too. I got to brag to my Dad about how I got closer to Spain than him.

I also like his work. His comics are great, I like how unique to him they feel, I like how he drew cars and sounds. His work feels to me like he was showing his freedom and what he could get away with.

————————

By 1982, I'd outgrown the superhero comics I'd read steadily through my teen years. To fill the void, I was buying all the undergrounds I could find at various long-lost quirky NYC comic shops like Soho Zat. As is typical, Crumb was the gateway drug. Fritz the Cat led quickly to Zap Comix, and while I loved nearly everything I saw between Zap's covers, I was particularly drawn to Spain Rodriguez's bold pages that looked as if they'd been drawn by Wally Wood on four hits of blotter acid. Spain was sketching a world I desperately wanted to visit: brutally violent, brazenly sexy and relentlessly hip. Spain's vision is a paranoid sci-fi fever dream where insidious corruption trickles down from the hidden seats of power, while leather-clad culture warriors fight that power in the name of the people's revolution. Good stuff.

Roughly a decade and a half later, in the midst of a notorious legal jam, I found myself reaching out to many "big name" cartoonists in the hope that I'd score contributions for my benefit book. I was struck by the generosity of Spiegelman, Crumb, Robt. Williams, Kim Deitch, and some of the other underground greats, but again, I was especially touched by the kind spirit of Spain Rodriguez. During a visit to San Francisco, Spain graciously spent most of a morning driving me around town in his vintage auto, sharing stories about the city he loved, his underground comix collaborators, and other anecdotes from the kind of life that would make any sane person green with envy. From the Road Vultures to the '68 Democratic Convention and the Mitchell Brothers' O'Farrell Theater, this was a man who'd been given a front row seat to the spectacle of mid-Twentieth Century America in transformation. Luckily for his readers, Spain had both the intelligence to understand what he was looking at, and the skill to share his insights with us in ways that were both moving and beautiful. In this instance at least, the cliched caveat that one should never meet one's heroes was entirely wrong.

————————

Jim Blanchard:

What strikes me about Spain was how calm, soft-spoken, and patient he was-- Hard to equate that with the ass-stomping biker he was early in life-- Maybe he got all his violent ya-yas out when he was young, I dunno-- I saw him maybe a dozen times in the last 25 years and he was always kind, and genuinely interested-- I remember being intimidated about calling him and asking him to contribute to a card set I was assembling in 1990, but he readily agreed and never mentioned money-- We spoke for 30 minutes about EC comix, undergrounds, and weird Topps sets like Mars Attacks and Civil War News-- His 60s and 70s work was an inspiration and influence on me as a young wise-guy artist in the 1980s, particularly his unique thick line graphic style and tough guy subject matter-- Also his beautiful, hand-separated color covers-- Big dot zip-a-tone was never employed better than by Spain-- Spain was a real life Working Class Hero whose art will live forever-- He will be missed!

————————

In 1967, Walter Bowart, editor of the New York underground paper The East Village Other (EVO), showed me the new comic they were running, "Zodiac Mindwarp", drawn by a guy named Spain. I liked the art -- it was strong, and you could tell he knew how to draw -- but the story was incomprehensible and awful. Shortly after that I met Spain and found out from him that he hadn't written the damn thing -- the writer had been Walter Bowart. I also found out we were both big Wally Wood fans, and thus began our friendship.

We didn't always get along. In 1968, when a bunch of us were crashing at the EVO loft, Spain threatened to hang my cat, and in 1970, when most of the New York underground cartoonists relocated to San Francisco, and I had become a full-fledged feminist, Spain believed that the sole purpose of the Women's Liberation movement was to turn women into Lesbians. But we remained friends through it all (I knew he wouldn't really hang my cat!) and in fact, during my very lonely first years of the '70s, when none of the other guys in the underground wanted anything to do with me, Spain stayed my friend.

In 1977, Steve Leialoha and I ran into Spain with Susan Stern at a movie theater, and I said to Steve, "Omigod, Spain has changed! Susan Stern is a strong feminist and she would never date Spain if he was still sexist!"

Spain's art was always excellent, his recent graphic novels are already classics, and he had high standards. I won't mention some of the things he said to me about certain other cartoonists! I collected the terrific posters he did for the SF Mime Trooup every year, and I have a great flyer he did for Earth Day that he signed, "For comrade Trina."

And here's something he drew in 1969.

I'll miss him terribly.

————————

Glenn Bray:

[Glenn sent along some little-seen Spain original art from his collection]

————————

The news came in via Ron Turner's email yesterday afternoon. My husband Justin Green was out running errands, so I called him from the house. It went like this: "Justin, pull over." "What?!" "PULL OVER NOW." "I'm in an intersection. you'll have to wait two minutes." I was glad for that gap of time because I knew what I had to tell him would be devastating.

For those who don't know, Justin and Spain were roommates for about a decade during the '70s/'80s. I remember visiting their place on Coso Avenue in 1982. Try to imagine a San Francisco bohemian-style bachelor pad, complete with a months-old turkey carcass in the refrigerator, nasty towels in the bathroom, and walls filled with great artwork and posters. I loved it.

They had been friends since the early days of the Undergrounds. And even after Justin moved out, they maintained the connection. Over the years, it's been funny to watch how much they grew to look alike as older gents, with their full heads of matching gray hair.

OK, so now the two minutes were up and I read the email aloud to Justin. He let out this agony-from the-depth-of-the-soul sound, like I've never heard before. Heartbreaking. And since then, quiet.

Except for last night. He recalled the time "when Dave Sheridan died. Spain got together all his toy soldiers, came in to my room and set them up there on the floor. I was at the drawing table and he was on the floor playing. We were just there together and neither one of us said a word."

Our best wishes go out to Susan and Nora.

————————

I have long admired Spain Rodriguez’s work. There is something so visceral about his drawings. They are not perfectly precise, but full of glorious life and dynamism. His work seemed rooted in the real and bigger world. I responded to his subject matter and his anti-establishment views. I was lucky to get a chance to work with him. I was in the middle of Safe Area Gorazde and broke. An opportunity came up to work with Spain on a multi-part Internet story about the Balkans through the writer and comics editor Bob Callahan. Bob’s story was a mess, but I needed the money, and I liked the idea of collaborating with Spain. I flew down to San Francisco to sort out our working relationship. Spain was a gentle and sweet man. I remember a display case in his house full of toy soldiers. I met him only that one time. We basically mailed strips back and forth and drew on the same panels. We were on the phone fairly often discussing scenes and dividing up the work. Early on, I called up to ask when the first batch of strips would arrive as they were quite late. “I’m blazing away on them,” he told me, but he hadn’t seemed to come that far next time I called up to inquire. He was still “blazing away”. I was beginning to panic. Then suddenly a whole mess of strips arrived. He seemed to have done them overnight, or that’s how it seemed to me. His parts were beautifully rendered. I’m thankful for that working experience with Spain even if the results can’t be counted among our best work. Spain was one of the great solid anchors of the underground comics scene. I loved his work.

————————

It was 1994, and La Luz de Jesus Gallery had a show for the upcoming Zap Comix artists. Everyone was there: Moscoso, Robert Crumb, S. Clay Wilson, Gilbert Shelton, and Spain. Juxtapoz just came out and they had an article about the Zap guys, so I got everyone to sign my copy of the magazine. When Spain signed mine, I asked him, "Hey, is it true that Moscoso will ask me for money to get his signature?" "Well, if he does, tell him I'll kick his ass," Spain replied with a twinkle in his eye.

So I go up to Moscoso, and say, "Hey mister, I want you to sign my magazine, and if you want money, Spain says he'll kick your ass if you do."

"Oh YEAH?" says Moscoso. "Gimme that pen!"

Moscoso then proceeded to sign HIS name in huge script over every other Zap guy who'd signed my magazine.

You just gotta love guys like that.

————————

“But he was alive just yesterday,” protested the youth.

That Spain’s passing was felt in a visceral way by so many is testimony to the greatness of his heart and spirit. I won’t add “soul” because that might touch off an argument with him. Like others who knew him well, we’ll be hearing his voice for the rest of our days and even as I tap out these words I can feel him peering over my shoulder. What a wonderfully explosive laugh he had!

On the evening of his death day, the full moon loomed low over the horizon in downtown Cincinnati. I was driving through the old city and the crumbling facades were evoking Spain’s architectural studies of Buffalo--those stark buildings which provided such compelling backdrops for those ink-noir Road Vultures scenarios. It is the rarest of artists who can enter our eyeballs, so that we apprehend visual reality through their aesthetic sensibilities. Now those sensational saucy sagas are finite in number. Had he lived until 2040, there would be countless more because his youth was a constant fount of inspiration. He had a phenomenal memory (going back to ‘42, when he was two). Now that body of work can be parsed and footnoted, as it

well deserves to be.

Who was the character that realized he had strong feelings for the dame who had been the plaything of the entire Road Vultures motorcycle gang? At a weekly meeting he testified of his devotional love to all fellow members, threatening that he would no longer tolerate disrespectful remarks directed at her. Does he show up in other episodes? Or what about those pizza proprietors in the African American neighborhood who wore holstered pistols while they served their dripping pies? You can’t make this kind of stuff up. Spain may have majored in art and minored in writing, but I believe the authentic social commentary and character development so pervasive in his work qualify it as true literature. More Beat than Hippie, he often coined phrases as he spoke with an effortless vernacular delivery that was uniquely his own (for example, Stalin “marshaled his ass-kicking forces.”)

Incredible as it might now seem, until the ‘80s you couldn’t write for publication without a typographer getting in your business; nor could you render oversize artwork for print unless it got processed by a photostat worker. In ‘75 Spain and I were the stragglers for a non-negotiable Arcade deadline. We had to bring our finished pages to a South-of-Market typographer and then hand deliver them to the printer. He arrived at my Noe Valley digs at dawn in his ‘53 black Buick. Though exhausted from the all-nighter, I was honored to ride shotgun in a mentor’s classy car that was vintage even then. He suggested that we take a detour through the financial district. As we wheeled slowly through the priciest real estate in town he spoke like a jaded tour guide, “This is the best time of day to check out chicks. They are totally buffed out in their finest clothes, fresh out of the shower. You can almost smell the shampoo.” I surveyed the local fauna with newly appreciative, yet bloodshot, eyes. Then, onward to the photostat place.

While we were waiting to have our work reduced to print size, I heard one of the clerks critique my “Gates Of Purgatory” panorama: “This guy is a faker.” I would normally have let the remark go and brooded about it for ten days, but in the presence of the great Spain, I was emboldened to defend my work. “Oh yeah?” I heard myself bellowing, “I’m a faker, huh? That’s why I’m out here and you’re in there!”

When I had to turn to sign painting for the survival of my new family Spain never abandoned me as a peer. In fact, he appreciated the art form. After the divorce, at the nadir of my life, he took me in as his roomie. I was lucky enough to have had a Japanese girlfriend for a couple seasons. We had major language difficulties, but she was capable of zingers. My favorite was “Room mate is happy man.” That was absolutely spot on.

Fully engaged in his work, his community of friends and fellow travelers, he was the polar opposite of me, a tormented religious nut with OCD and major relationship problems. Our dynamic was replicated in our drawing styles. He would be ensconced in an easy chair in front of a day/night TV, dashing off authoritative and bold ink lines from minimum penciling. If I wasn’t painting a sign, I’d be hunched over a standard drawing table. My preliminary pencil drawings would be the pretext for halting tentative ink lines that would require additional cross-hatching and a fair amount of white-out. In the years of working near him, I made a quantum leap in skill because I gained some of his pen command through osmosis. He was a cartoon Zen master. You’d have to have some skin in the game to understand the courage it takes to slash bare white space with a bold inking technique. And it also takes a lot of guts to draw the title/splash panel first, then come up with the story later, but once in awhile, he did just that.

Back then, the only mouse in our house was a real one. Everything was hand-made, even Lost Dog notices. We didn’t think of ourselves as “content providers,” though in the new computer age we would all gather under that umbrella. It still surprises me that he was one of few original Underground artists able to transition to the computer, while still maintaining the integrity of his traditional craftsmanship. But long before he became a master of Photoshop we had parted ways.

I never knew him as a family man, either. By the time I moved, his roving eye became locked on a certain beautiful and talented woman who would later bear his child. I started a new family, too. Large chunks of time passed between our visits or calls. But when we connected, it was effortless. His lively intelligence and political awareness revealed that his zest for life had only increased. His output continued to be prodigious and showed no signs of faltering. His taking on the Che project when well into his ‘60s is the crowning achievement of a career that never faltered. He was productive to the very harsh end of his life. More importantly, he remained kind and conscious, forever to be beloved by friends and family.

————————

So, the great Spain is dead, gone from this world. His troubles are over. He had a full life. He was a working class hero, the only person I ever knew who was a bona fide card-carrying Communist, a rank-and-file member of the Communist party. His hatred of bourgeois values never dimmed, never diminished. You could count on it. He was crystal clear about it. It wasn’t just an abstract stance with him, it was a visceral, abiding hatred. Spain had strong sympathies for the Soviet Union and a rare level of knowledge of its history, its inner workings, its culture. I suspect that it was to some extent a posture of defiance, a way to give the finger to American bourgeois capitalism. You can read all about it in his many comic stories. His proletarian origins and youthful rebellion are well-documented in his work. The stories of his youth in Buffalo are a unique graphic glimpse into blue collar American life.

I first met Spain in New York in the fall of 1968. He was living with Kim Deitch and doing a one-page strip for a weekly “underground” paper called The East Village Other. Kim was also doing a weekly strip for this paper. Spain had left Buffalo for good, left the world of outlaw bikers behind and embraced the East Village hippie scene, though there was a lot about the hippies that Spain didn’t like. “I ain’t no hippie,” he used to say. His allegiance to radical left-wing politics and his proletarian class identity were stronger and clearer than most of the youths in the hippie subculture, the “counter-culture,” as it was called. His politics were driven by genuine, authentic class anger, class hatred. I liked that about him. It was always clarifying, bracing, to discuss politics, social and cultural issues with him. Plus, he had a sharp sense of humor which leavened that anger. He was not your typical “humor-impaired” leftist, nor was he a dogmatic Marxist, spouting slogans or left-wing terminology. I appreciated those discussions with him, as he helped clarify certain things for me, politics, economics, history. He was well-read, self-educated in these areas.

Spain was an atheist. He despised religion. He even had contempt for Eastern religions and viewed the fascination with Hinduism and Buddhism as bourgeois decadence. He also had a certain contempt for the animal rights activists. “I’m at the top of the food chain and I’m proud of it,” he once said.

He also could make some great lasagna. Now that I think about it, geez, I’ll never again be able to go to his house and have that delicious lasagna of his. Wow... he’s really gone. It’s starting to sink in...

————————

There is no perfect time to tell someone their dearest friend has died. I learned of it moments before I planned to bathe Wilson and take him to his doctor. Not a good time. In the following two days, I couldn't reveal it right before going out on errands, leaving him alone with a caregiver. And an evening announcement would be too painful. So I settled on Saturday morning, when I knew Paul Mavrides could come over with his abundant supply of comfort and laughter. When he arrived, Wilson stretched out from where he had curled into a ball on the bed, and Paul stayed beside him for nearly two hours, swapping tales about their friend. It was exactly what perhaps they both needed.

S. Clay Wilson and Spain went out to lunch in North Beach at least once a month for the past 12 years, since I'd moved in with Wilson. But it had been their tradition long before I arrived. (When he returned, belly full, Wilson would often lie down for a nap, announcing that Spain sure could eat.) Every now and then they would invite me along, and occasionally I accepted. I never got a word in edgewise, of course, but I didn't mind, as I loved listening to their rapid-fire conversations.

When Wilson suffered a traumatic brain injury four years ago, I asked Spain to be the conservator of his estate. This was a tedious process, involving numerous trips to lawyers, Social Security, the bank, and appearances in court. I always went with Spain on these frequent (and frequently annoying) appointments. I loved riding along while he told me stories from his youth, stories about Wilson, art, politics, and heated rants about our mutual hatred of bicyclists. I grew to love Spain like a brother. He was a loyal friend to Wilson, and was gently patient with me and all the decisions that came with his care. I could depend on his counsel and support.

At Spain's house, there is a room filled with his incredible toy soldier collection. They are pristine, under plexiglass. When he visited us, he would often stand at our mantle, chatting with Wilson while meticulously cleaning the crowded collection of figures living there. You could always tell when Spain had been by, as you could see where he'd stopped dusting.

When I had a benefit at 111 Minna for Wilson in 2009, Spain sat at a table nearby, drawing. When I'd finished, I approached the table to see what he'd been doing. "Oh, I love that!" I announced. "It's not done," he said, "but you can have it." He signed it sideways, and handed it to me. I have had it framed and on the wall ever since.

I will miss his fertile mind, his biting sarcasm, his irreverence, and his sudden laugh. Mostly, though, I will miss his kindness and his company. Ride easy, dear Spain.....and keep it on one wheel.

————————

————————

Haven’t been able to put Spain’s bones to rest in my head since last Wednesday morning’s call from his wife, Susan. Ever since late May when Crumb, who’d just visited him, told me he was seriously ill I made a point of staying in more regular phone contact. Mostly Spain sounded so much like himself, and remained so fully engaged in his work, that I wasn’t braced to find out he had actually Checked Out in the middle of his still high arc. He drew til almost the end and died at home with beloved wife and daughter at his bedside—but he deserved more pain-free time, though that has nothing to do with how things work.

Shit! I remember when 72 used to seem Ancient-Egypt old!

I don’t know how to conjure up Spain’s combination of passionate engagement, curiosity, intelligence, humor, humble-but-proud self-acceptance, his fiery idealism, and his warmth... though all these attributes can somehow be found in even his most feverishly hardcore comix.

I first met him in the Lower East Side in ’67, at the beginning of the EVO days. The eight-year gap in our ages made him seem like a full-fledged and potentially dangerous grown-up, what with the leather jacket and gangbanging biker talk. But the aforementioned warmth kicked in right away and the 19-year-old insecure-and-paranoid-hippy-wimp incarnation of me found a reassuring older brother. I saw him get downright pugnacious a couple times, but the only time he raised a fist near me was to show me how to draw one so it would look less like my usual cluster of bananas. (I still haven’t gotten the hang of it, but remain grateful for the lessons and for his acceptance and interest in what I was doing even before I was sure what that might be.)

My memories overlap with so many already posted here. I remember riding on errands in his jalopy back in the Arcade days and his useful pointers about (and at) women; and I remember visiting him a few years back, sitting on his stoop so I could smoke after eating his homemade powerhouse lasagna. We’d talk for hours about art (we argued about Warhol, since there was a poster of the Marilyn print in his kitchen and Spain—for all his Marxism—had a lot more sympathy for the old huckster than I could muster) and we gassed about comics, our kids, movies, politics and all the usual. He said something wistfully positive about Stalin and I quoted Sue Coe (my only other unreconstructed Commie Friend) who’d told me: “the main thing wrong with Stalin was, he just over-purged.” Spain laughed hard but said he knew where she was coming from. In all our conversations he’d at some point veer off into a blow by blow description of a WWI or II military battle he’d been reading about or a detailed synopsis of a movie he admired and invariably lost me somewhere. But I sure enjoyed his cadences and enthusiasm.

Looking through decades of his work over the last few days, I realized that I’d sometimes get lost following the storylines of his comics as well, tho the cadence of the drawings kept me with him, and he sure got the storytelling consistently under control over recent decades in the lifelong and relentless pursuit of his craft. His drawing always reminded me of rock-solid carpentry built out of rough-hewn lumber. Despite his serious chops and his testosterone charged adventure comics influences, his art was just too quirky and filled with too much conviction to veer into the glibness that could’ve found him a comfortable home at a “mainstream” comic company. It’s what made him an underground comix star.

I remember visiting him once in the '70s while he was working on a very long story. He had piles of pages strewn all around the room. Some were ruled out and partially lettered, some boards were only lightly pencilled with intense rendering on only one or two scattered panels, some almost empty with just a car or a torso randomly inked. I was baffled and asked if he always worked that haphazardly since I’d have blown a fuse trying to get anything done that way. He said he figured as long as he kept his hand moving it would all get done eventually.

A stray memory (I apologize for the randomness of these thoughts, I just figure if I keep my keyboard moving it’ll help me get the bones to settle): Walking down Telegraph Avenue in the early '90s with Spain on one side and Bob Callahan, his collaborator and my one-time friend, on the other. Anyway, one of em on each side, both looking like versions of Jimmy Rushing’s Mister Five by Five. We needed a wider sidewalk, especially because all three of us were prone to gesticulating wildly while talking. First I’d get squeezed out of our formation, then Spain would be forced off the curb, and nobody trying to walk by us could possibly get past our moving human blockade. Sigh. In our last phone call a few weeks ago I asked Spain how he was doing and he said he’d lost a lot of weight but that he didn’t recommend this method to anyone.

Callahan died about four years ago and Spain stayed close, visiting him in the hospital right up to the end. He cajoled me to make contact with Bob when he was slipping, but some unhealed wounds kept me from doing it. Spain had plenty of reason to harbor some similar feelings, but— have I mentioned Spain’s generous spirit?

Funny to think of Spain as a Road Vulture, though he conjured up his tough guy days with great precision in his recent Cruisin' with the Hound anthology. He brought his dead-end friends to vivid life, a slice of life I’d never wanna get within miles of in the real world, but was thankful to see through his comics panels. It’s as if he escaped his “misspent youth” by finding some sort of redemption (though not the Catholic kind) by devoting himself to art—to drawing the violence rather than living it—and he matured into one of the greatest Mensches (though not the Jewish kind) that I’ve ever been lucky enough to know. As I've done for the past few days, I’ll crank up my old Russian language version of the Internationale again tonight in his honor.

————————

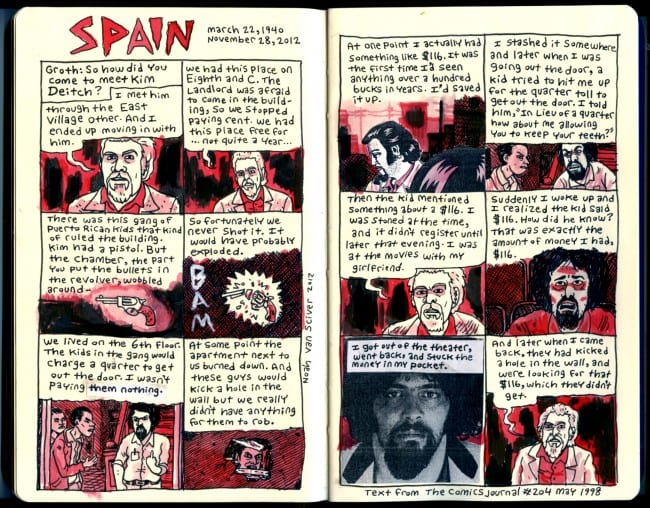

I had the privilege of publishing most of Spain’s book collections, four in all: Trashman (1989), My True Story (1994), Nightmare Alley (2003), and his last book, Cruisin’ with the Hound, earlier this year (2012). I also enjoyed spending many hours with him conducting a 50,000 word interview that appeared in The Comics Journal in 1998. So, my relationship with him was both personal and professional, and the two were essentially seamless — publishing him seemed to me an act of or an extension of our friendship — or maybe it was the other way around, it was hard to tell.

Once I got a decent handle on comics history (sometime in the ‘70s) I came to admire the underground comics artists, thought of them then, as I still do, as the artists who dragged the comic book out of the artistic dark ages and moved the form definitively from a commercial medium with adumbrated or compartmentalized bits of artistry to a full-blown, unified personal form of expression. However unostentatious, they thought of themselves as genuine artists, refused to compromise, committed their lives to their art, and didn’t take guff from publishers — which was a different work than mainstream comics. I made it a point to publish interviews with and reviews of underground cartoonists from the early days of The Comics Journal, despite the fact that underground comics had by then become nearly moribund. The very first “graphic novel” we published was by a compatriot of Spain’s, Jack Jackson, who, like Spain, maintained his fierce integrity until the day he died. Once Fantagraphics established some momentum publishing comics in the early ‘80s, one of my grand ideas was to republish underground cartoonists in book collections. To this end, I talked Robert Crumb into letting us publish The Complete Crumb Comics (comprising 17 volumes) in 1987, with others to follow.

I was a little too young to have experienced the underground comics in their heyday, so by the time I discovered them, they were already surrounded by myth — at least to me. I’d read enough of Spain’s comics so that the anticipation of meeting this blue-collar, ex-biker-gang-member, Marxist ass-kicker was both thrilling and intimidating. But, in fact, it turned out to be charming and low-key. I forget the exactly circumstances, but I visited Spain’s apartment in San Francisco in the mid ‘80s and he took me out to a local pub. I remember very little about it, except that he was convivial, put me at ease, and discourses at length talked about the Russian Revolution, about which he had a deep knowledge, and that we got along swell. By the time I met him, his hell-raising days were behind him, but I could still see the tough guy beneath the surface. He just channeled that energy into his political commitments, about which he never wavered. Unlike most ideologues who can be shrill and one-dimensional, Spain was firm but charming.

I kept in touch, and at my urging we assembled a collection of his Trashman comics in 1989. Five years later, we published a collection combining autobiographical stories and historical pieces under the title My True Story, which held a double meaning, of course — true in both the experiential and historical senses.

Spain was always easy to work with. Partly this is because he was incredibly unfussy. He was all about the content, let the packaging up to us, and was mercifully uncritical about it. (The design of those first two books makes me cringe a little, but they served the purpose at the time. We upped our game with the next two and I’m pleased with both. I look forward to one day seeing a more comprehensive series of Spain books.) Spain was a street-smart intellectual and a meat and potatoes artist who felt he could tell truthful stories without any frippery. He was heavily influenced by EC comics (as most of the underground cartoonists were) and Jack Kirby (as most of the underground cartoonists weren’t) and he often displayed the same puissant storytelling physicality as Kirby — Kirby’s short “Street Code” is certainly a narrative kissing cousin to Spain’s stories of youthful carousing in Buffalo. This lack of formal play was evident even in his inking, which was carved out in heavy, solid, no-nonsense lines and sensual, tactile brushstrokes, as well as in his crowded compositions, bursting at the seams and packed with information, each panel a fully realized picture. Sex and violence were constant elements in Spain’s stories, but there was almost always something else going on beneath the surface — social observation, political undercurrents, an inner life. His characters fucked and fought and bled.

I learned that Spain had cancer during the production of Cruisin’ with the Hound. I lived with this knowledge for nearly a year, during which I was lulled into a false sense of … denial. Every time I spoke to Spain, which was often during the six months or so his book was in production, his voice sounded strong and he sounded optimistic. And I wanted to believe he’d beat it. I don’t know if he was genuinely optimistic himself or putting on a false front, but he handled it with understated grace.

Mutual respect is important, of course, but comradeship is something else again, and that’s what I always felt with Spain, from practically the first time I met him, an implicit acknowledgement that we were on the same side. That meant a lot to me.

I can’t imagine two artists being any more different, but I remembered something that Richard Ellman wrote about Joyce: “The function of literature, as Joyce and his hero Stephen Dedalus both define it with unaccustomed fervor, is the eternal affirmation of the spirit of man, suffering and rollicking. We can shed what he called ‘laughtears’ as his writings confront us with this spectacle.” That’s how I see the twin pillars of Spain’s life and art — suffering and rollicking, full of ‘laughtears.’

————————

When I was about 11 or 12, there was a bookstore in my hometown where they didn't mind us not buying anything and sit around reading their comics. This would have been about 1980 or '81 or so. One day there were these other comics. They cost a lot more than the other comics, and were black and white with no ads. Even though they said “Adults Only” on their covers, the owner of the store didn't mind us reading and buying them.

One was this new magazine called Weirdo. It was put together by Crumb, but also showed the work of his contemporaries. It cost a little bit more than my allowance, so it was one that I sat in the store to read. In the second issue was a story called "Big Bitch". The last panel had something none of us kids had seen before. Big Bitch was getting her vagina licked. It was beyond anything any of us knew about. Sure, somebody had told us what blowjobs were (one kid even claimed to have gotten one), but nobody had any idea it could also be performed on women. It wasn't in any of the magazines anyone hid under their bed, so every kid in town had to see this comic. It may be debatable among the few recipients whether I was ever good at it, but I credit this comic with being the first instance of seeing the concept.

One was this new magazine called Weirdo. It was put together by Crumb, but also showed the work of his contemporaries. It cost a little bit more than my allowance, so it was one that I sat in the store to read. In the second issue was a story called "Big Bitch". The last panel had something none of us kids had seen before. Big Bitch was getting her vagina licked. It was beyond anything any of us knew about. Sure, somebody had told us what blowjobs were (one kid even claimed to have gotten one), but nobody had any idea it could also be performed on women. It wasn't in any of the magazines anyone hid under their bed, so every kid in town had to see this comic. It may be debatable among the few recipients whether I was ever good at it, but I credit this comic with being the first instance of seeing the concept.

The owner of the bookstore was able to expand his inventory of underground comics as more were going back into print. Later, I discovered Zap Comix. Of course, I recognized the slapstick antics of Gilbert Shelton and the all-around cartooning of Robert Crumb, two of the artists that stood out from the comics a couple years earlier. S. Clay Wilson and Robert Williams were too busy for me to comprehend with my still-forming brain, and Griffin and Moscoso I knew even then were trippy sixties drawings, but I remembered the work of Spain (I had no idea what his last name was) from the cunnilingus comic I had seen earlier. His work looked closest to the EC Comics my father had saved from his childhood. (When I tell friends my father saved these comics they say, “He must be so cool!” No, just a packrat.)

By then the other kids went on to other pursuits and I was still reading comics. I was now able to appreciate these comics for the art and not just because they were dirty. I had also discovered Subvert Comics and some of the more “serious” underground titles. There was a comic store now about 50 miles away I was able to visit every few months that sold comics you couldn't get at regular newsstands. They were mostly the same as newsstand comics, except with nudity. It was the '80s, before what we would call comics was considered a completely different entity from Marvel and DC. When anything that didn't have a bar code was considered “out there.” There was an anthology from a then-nascent Fantagraphics called Prime Cuts. Prime Cuts had the work of a lot of newer cartoonists, but a few of the older underground artists, one being Spain (I was finally able to find out his actual name that was "Manuel Rodriguez"). But instead of the Marxist superherodom of Trashman or the proto-feminist adventures of Big Bitch, these stories were more introspective, showing his memoirs as a delinquent greaser biker.

Anyone who does comics not for hire owes their existence to the first generation of underground cartoonists. They were the first not only in being uninhibited (and not doing heroic fantasy); they were also DIY pioneers long before the punk movement. Such a thing may not have even occurred to anyone before. Now even though what they do might still be “kid stuff” in some circles, it's taken for granted you don't have to answer to “the Man.” Nobody says “you can't do that in a comic book” anymore. I may bemoan the literary and high art aesthetic in comics today, but I'm glad it can be done without question. Independent comics would not have basically melded into underground comics. There wouldn't be additional venues. “Comics aren't just for kids any more” would still be the opening line of every article that mentioned comics, not just the magazine for the proverbial “old lady in Dubuque.”

Spain Rodriguez is not the first of the original generation of underground cartoonists to go, but his passing reminds us now that many of them are in their sixties and seventies and facing mortality themselves. He did his first comics in his late twenties, a reminder that it's never too late for anyone to start. Soon all will have left us. Not only will we not be able to see new work by the artists we grew up with and watched mature, but how will pre-adolescents get their kicks?

Godspeed, Spain Rodriguez.

————————

Impact was the title of an EC comics series, one best remembered for featuring Bernie Krigstein’s immensely influential “Master Race” story in its first issue. I’ve always loved Impact as a title because its so suggestive of the aesthetic that EC Comics both pioneered and passed on to young readers like Spain Rodriguez. The best EC stories left a mark on readers, they possessed a fervent intensity in their image-making that was hard to forget. The chief lesson that Spain learned from EC, one that never left him, was that comics have the power to make a difference, to have an impact. Like the comics he loved as a kid, Spain’s best work wasn’t cerebral, cool, detached, abstract, or disinterested; rather it was in-your-face, blunt, abrasive, visceral, partisan, raucous, and incendiary.

Impactism, if we think of it as a philosophy, had implications for life as well as art. Since his death, many have testified to the impact that Spain the man had on them. These memoirs uniformly testify to a warm, hearty, lively, engaged, and earthy man, a man who even in pursuing the relatively reclusive or hermetic life of an artist still managed to leave an impression on all those who met him.

Unlike those who knew Spain, my encounters with him were second hand, mediated through print and also the passage of time. I was a mere babe in arms when Zap Comix #1 came out in 1968 and ignited the underground comics movement, so I encountered Spain’s pivotal early work many years after they were first published. I first saw Spain’s comics when I was 11 when I came across Comix: A History of the Comic Book in America (1971) in the library. Rather remarkably, this book reprinted some key underground works, albeit PG stories rather than the genuine X-rated stuff. It was in Daniels' book that I first read Crumb’s “Meatballs”, Kim Deitch’s “Doc Destiny”, and Spain’s Manning the cop (a two-fisted satire on police brutality). It took another few years before I encountered more of Spain’s work when I finally found a store that sold old copies of Zap and Arcade.

The 1980s of Reagan and Thatcher was a very different time than the 1960s and early 1970s. Yet despite the passage of time, the best underground comics had lost none of their urgency, none of their punch, none of their impact. This was especially true of Crumb, Deitch, and Justin Green but also of Spain, who belongs with those three on the small list of my favorite underground cartoonists.

Aside from Chris Mautner, I’m not sure if anyone has noted how versatile Spain was in the number of genres he work in. As Mautner noted, Spain did “just about everything – sci-fi, noir, literary adaptions, satire, political gags, sometime all rolled into one.” The underground movement was divided in various camps but Spain managed to straddle these differences and do work with both the angsty intellectuals (the historical strips he did for Spiegelman and Griffith’s Arcade) and the more lowbrow genre-inflected entertainers (the EC-influenced artists of Slow Death Funnies). Spain is perhaps the only cartoonist who could usefully be compared to Spiegelman, Harvey Pekar, Wally Wood, Jack Jackson, and Jack Kirby.

Mautner also went on to note that Spain’s best work was his autobiographical stories, a judgement I share although I would expand it to include his historical work. The series of stories about the Road Vulture Motorcycle Club that appeared in Zap deserve to be singled out for their ferocious unapologetic honesty. As far as I know, no one else has ever described the world of a biker gang with such intimacy and accuracy. What united Spain’s autobiographical stories with his historical studies was his fierce and unforgiving class consciousness, a property which is incredibly rare in modern North American culture. His plebeian defiance was the source of his artistic energy, the fire that drove him to fill countless pages with impassioned drawings.

Spain’s work had an impact on me and countless other readers. He will not soon be forgotten.

————————

Sharon Rudahl:

I remember reading Trashman in the East Village Other and being blown away, at a time art in New York meant all black canvases and featureless steel cubes. Visiting Spain's home in Bernal Heights as a beginner cartoonist, I felt welcomed and treated with respect. I recently participated in a 40th anniversary of Wimmen's Comix show in San Francisco, and several women agreed that Spain was unique among the male cartoonists. Not only was he not a jerk who came on to us or patronised us, he actually volunteered useful graphic tips.

Many times over the decades, when I have doubted if there was any point in continuing to draw comics that aspired to more than crude entertainment or shallow shtick, "Spain" was always the name that came to mind. Spain kept to his own high standard all these years, kept working for peanuts or nothing to support worthy causes, kept pushing himself to share his vision.

There's so much more press about assorted comix artistes, with one eye on their navels and the other firmly on the bottom line. Spain was the real thing. It was an honor to know him.

————————

I don’t know where to begin. I’ve been reading all the great posts here all week. I’m glad they’re here. He won’t be forgotten. That is crystal clear.

All my life I’ve been pretty lucky. I have work I enjoy doing. I stumbled into a vocation that I love and it keeps me going. I had the great fortune to be in the right place at the right time to get in on the ground floor of an exciting art movement. A major part of that good luck was rooming with Spain for a key year and change of that early time. It wasn’t like we had a lot in common. Spain wasn’t really a hippy although I think he was more so at that time than some may remember. I didn’t see much in his political point of view. By the time I’d left home I’d had a bellyful of left wing politics and was just getting over a few years of considering myself a Republican when I first met Spain. Parental rebellion takes curious roads sometimes.

More to the point I was younger than Spain and far less accomplished than him as an artist at that time, and even considerably less accomplished as an adult human being. He knew it and showed a lot of patience toward me. He was a true friend to me in every sense of the word. I learned from him.

The first thing I learned was pretty superficial. Spain always had a way with the ladies. I studied him in action and almost overnight got to be twice as good at picking up women myself; but I digress.

He was tough on me over my lack of drawing chops, as well he should have been. He gave me a much clearer idea of what it was going to take if I ever expected to get anywhere as an artist. I didn’t always realize it at the time but this was a priceless gift.

We had all kinds of crazy adventures. These are yarns I could dine out on for the rest of my life if I had nothing better to do and, frankly, I’m glad others have brought some of that stuff up in this forum so I can pass over it.

He was an amazing artist. I can’t think of another artist that I have known, Crumb excepted, who had a better stockpile of drawing chops at the beck and call of his drawing hand than Spain did. It was quite astonishing and a little daunting sometimes too. It seemed to be almost beyond his complete control. What I mean is, it came out anywhere and everywhere. There were virtually no digs where Spain spent any amount of time that didn’t seem to have an ongoing mural by Spain on it in progress. Archeologists will probably be unearthing these in various states of completion for years to come. And as many more will probably be lost forever. That’s just the tip of the iceberg. He left little pieces of his monumental artistic talent virtually everywhere he went. I remember one time that I was visiting Spain, and there was a porno paperback lying around. I picked it up and in the large space on the page at the end of every chapter was and anatomically correct drawing of some activity that the chapter covered, a beautiful spontaneous Spain original. Where is that book today? Where so many other similarly wonderful pieces of art that Spain produced on his journey through life?

————————

I feel a bit sheepish about submitting one of these tributes to Spain, because I never met the man, although I’m a long-time reader and admirer of his comics. After his passing, I found myself especially curious about Spain’s life before he began his career as an underground cartoonist (as Sam Henderson notes, he “did his first comics in his late twenties”), in part because we were both born and lived our formative years in Buffalo, New York. I decided to contact some fellow Buffaloians to see what they could tell us about young Spain.

Before I begin with these first-hand testimonies, however, I should talk about the political and social climate in Buffalo during the 1960s—especially at the State University of New York at Buffalo, a school typically called “UB,” the University of Buffalo, by locals. In the 1960s, UB was a campus in full counter-culture bloom. In his book High Hopes: The Rise and Decline of Buffalo, New York (1983), urban studies scholar Mark Goldman described UB’s 1960s energy in these terms:

Enrollment had grown rapidly and steadily since 1962, not only increasing the size but dramatically changing the character of the student population. An increased number of New York Jews—the children of cab drivers, high school teachers, and civil servants who now could for the first time afford to go to college—now poured into Buffalo, bringing with them the excitement, color, and creative dynamism of their culture and their city. By 1967 UB had become the most stimulating and avant-garde cultural showplace in all of Western New York. (252-3)

UB students also participated in the leftist political activism that characterized the late 1960s, often provoked by events specific to Buffalo politics. In April 1964, for instance, the members of the House Un-American Activities Committee traveled to Buffalo for hearings designed to ferret out “communist activities” in the community and the UB faculty. The Buffalo left—a loose and not-always harmonious assembly of students, community organizers and union leaders—responded by organizing successful, highly publicized protests against HUAC’s presence in the city.

One of the men I contacted about Buffalo’s 1960s counter-culture history was William Sherman, a prolific and well-regarded poet with several chapbooks (among them Heart Attack & Spanish Songs [1981] and Tahitian Journals [1990]) to his credit. According to Bill, Spain “was a huge presence on the scene, but I wasn't ‘close’ to him (or to Cindy [Spain’s sister], though I remember we went out once). In fact, it wasn't all that long after meeting Spain that I finished my doctorate and taught film that summer, and then headed off to England where I had been offered a university lectureship.” When Bill heard about Spain’s death, he wrote a poem on his blog about Spain’s role in the HUAC protests, presented here with Bill’s permission:

Spain: Buffalo DaysHunched in an old felt green armchair at 1001 Lafayette Ave.

Must have been Jeremy Taylor introduced us all

Because of the demonstrations against HUAC.Hunched over a small acoustic guitar,

He played in the classical style

Almost painfully sweet these melodies he was inventing

Moreso coming from a man of such power.He had drawn the cover of Landscape of Contemporary Cinema

My first published book, co-authored with Leon Lewis.

His work even then defined Iconic.

And Cindy, writing short stories under the name N. Howard.Riding security with the Road Vultures.

Protecting by this act many young undergrads

Otherwise might have been beaten that day

During the protest at the McCarthy-era Committee's

Leaving D.C.'s confines first time in years....

Given the keys to the city, Buffalo, 1964.Around the monument across from City Hall they rode

Spain in the lead, holding aloft

(Was it in his right hand, or his left?)

The black anarchist flag

Of the Spanish Civil War.It was truly a sight to behold!

As stated in the poem, while in Buffalo Bill co-wrote a book, Landscape of Contemporary Cinema (Buffalo Spectrum Press, 1967), with Leon Lewis, then a graduate student in English at UB. (Leon is now my colleague at Appalachian State University in North Carolina, and it’s thanks to Leon that I’ve been able to connect with the Buffaloians who remember Spain.) Leon told me that many people called Spain “Manny” back then (Spain’s given name was Manuel Rodriguez), and that Spain and the Road Vultures actively participated in the era’s protests and events. Leon also said that he also didn’t know “Manny” too well, although he loved Spain’s illustration for the cover of Landscape:

Also mentioned in Bill’s poem is Jeremy Taylor, a 1960s Buffalo activist that I also contacted. (Jeremy is now a Unitarian Universalist minister and dream interpreter.) Like Bill and Leon, Jeremy cautioned me that his encounters with Spain weren’t intimate: “I need to tell you that I had virtually no face-to-face contact with him other than in relatively large, public venues, where we acknowledged each other's presence in a very friendly fashion, but seldom even talked directly with one another.” Still, they collaborated on at least one project:

My most satisfying and intimate connection with him was when I was Editor of the SUNY at Buffalo student newspaper The Spectrum. I introduced a comic strip called Suny Daze which I wrote and drew myself at the beginning, and when it was threatening to become the tail that wagged the dog of my journalistic life, I prevailed on Spain to draw it from my scripts—which, I think, makes me the first person to collaborate with him as comics artist, as well as the first to offer Spain a regular outlet in a periodical (weekly) for his work.

Even when he was doing the art work for my scripts, we seldom talked! His vision and mine meshed so smoothly, I had no reason to do anything but congratulate him and thank him each week when and even more brilliantly drawn strip than the week before appeared in The Spectrum!

I haven’t been able to find any samples of Suny Daze, though I would love to read some. Likewise, in an e-mail to me, Jeremy also mentioned Spain’s sister Cindy: “I did have two fairly deep political/cultural conversations with [Spain’s] sister, in which she mentioned her brother's views as having a great influence on her own. From those conversations, I gathered that ‘Manny’ was more of a Marxist than I ever was, although we shared a hero-worshipping interest in Buenaventura Durriti, and some of the other populist anarchists.” Is anyone currently in touch with Cindy? I would love to read a tribute from her.

The messages that Jeremy sent to me also address the Buffalo biker culture that he and Spain shared. Let me quote extensively from an e-mail from Jeremy:

The local (Buffalo Police) “red squad” regularly harassed us both. They were convinced that Spain and I were “co-conspirators,” mainly because we both rode motorcycles, (without ever noticing that we never rode together!). All that stuff about the “Road Vultures” in Spain's comix is true, at least to the extent that they describe events and attitudes, some of which I experienced directly, and most of which I heard about second-hand. They really were bad asses, just as Spain described.

I knew the Road Vulture “fellow traveler” Tom Bell (see page 19 of My True Story [1994]) in some ways better than Spain himself, because, although he was also loosely affiliated with the Vultures, Tom preferred riding Triumph motorcycles to Harleys (a detail that shows up in Spain's affectionate portrait). Tom would occasionally show up riding solo at some of the same bars and other hang-outs that I also frequented occasionally, and he and I would talk—often about Spain, the comic strip, and Buffalo police/mafia gossip generally.

Later in Jeremy’s message, a note of uncertainly and critique about Spain’s involvement with the Road Vultures creeps in:

I confess that I have always wondered why Spain worked so hard to neutralize the Vultures’ notorious and inescapable racist bullshit. In retrospect, I realize that it was a stunning achievement, one that Spain must have taken some considerable pleasure in! His full, public membership in the “club” was, as far as I could see at the time, a direct result of what a brilliant, talented, uncompromisingly cheerful and tough guy Spain was. It always seemed to me that that the Vultures made a special exception, in his case, for him alone. I always wondered, why—and even how—he managed himself when their racist crap erupted in confrontation with others when Spain was physically present. I never heard any stories about that, not even from Tom Bell, whom I actually asked about it…

The main problem from my point of view was that I had no taste for the brawls and other drunken bullshit that the RVs regularly engaged in, to the extent that the few times when they showed up en masse at the same locations that I was already at, I usually saddled up, waved cheerfully to Spain (who waved back, also cheerfully), and then I rode off, only to hear days later about the fights and police actions that almost always followed.

Spain was a deeply “affiliated” biker, and I was deeply “an independent.” He rode Harleys, and I rode BMWs. He wore black leather, and I wore brown. He didn’t wear a helmet, and I did (even before it was legally mandated in New York State). We never rode together, or talked politics face-to-face, always beginning “in the middle” with the shared assumption of our mutual distaste for “fascism” in all its serpentine permutations.

I’m very grateful to Bill, Leon and Jeremy for sharing their memories, and I’m especially struck by Jeremy’s aversion to the Road Vultures—it’s easier to read about their exploits in My True Story than it was to be the real-life target of their anger and prejudice. Yet I also discovered information that made me respect Spain more than ever, especially Spain the rebel, Spain the Road Vulture who protected the HUAC protesters from the police, Spain the man who stood against The Man in my hometown.

————————

Charles Dallas:

Barely twenty years old, I arrived in San Francisco in 1972 with little more than a portfolio of comics I had drawn and the desire to become an underground cartoonist. My first stop was Gary Arlington’s San Francisco Comic Book Company in the Mission District. Gary must have seen something that he liked in my amateurish efforts and suggested I pay a visit to Jack Jackson. Jaxon became a generous and helpful friend and mentor, and at some point introduced me to Spain Rodriguez. Spain was a little intimidating, not because he was brilliant, opinionated, and incredibly talented; he was all those things, but always remained down to earth and was a genuinely nice guy. He was intimidating because he was one rough dude you would not want to mess with. But he was also very friendly and eager to help me develop as a cartoonist. I was just a kid, not on his talent level at all, but he was kind and supportive and eventually invited me to submit a story for his great horror anthology, Insect Fear. I remember when I showed him the artwork, he said, “Yeah, this is ok, but you have to make it more scabrous.” I had to go home and look up "scabrous" in the dictionary. Of course he was right, and he was definitely the expert when it came to making things look scabrous.

One time we sat on a panel discussion together at a small comic book convention in Cotati, California. Someone asked if it was necessary to study anatomy to draw comics. I said yes, you need that background and training before you can take off on your own. Spain said no, just do your thing. For him, that worked. He had so much talent that he did not need that reference point. Drawing for him was easy and natural and the images flowed like water from his mind’s eye, through his hand and out onto the paper. I remember being at his house and marveling at how he could sit on the floor cross-legged with a drawing board on his lap and just draw, undeterred by whatever commotion was going on around him. No preparations or fancy equipment were needed, no rituals were performed; he barely even sketched in pencil before inking. He just drew and he was the Zen master of his art.

I once mentioned to Spain how depressing it was to be between projects, unfocused and unsure of what to do next. He somewhat incredulously replied that he never had that problem, that he always had a million story ideas and couldn’t wait to finish one and move on to the next. Judging from the body of work he produced, he never lost that enthusiasm and creativity.

I hope someday he gets the credit he deserves as one of the greatest artists to ever pick up pen, brush, and ink. It was an honor to have known him. Thank you, Spain.

————————

M.K. Brown:

I first met Spain (he was Rod Rodriguez then) at Silvermine Guild, a small art school in Connecticut. We were about 19 and exploring what we were meant to do as artists. Neither of us actually graduated, but we certainly benefited from the variety of media and teachers the school offered. My future husband, B. Kliban, also attended Silvermine Guild, which is strange, given the school's limited size and non-interest in cartooning at that time.

We didn't meet again until the early ‘70s at a party in Victor Moscoso's garden. I was introduced to a fellow named Spain, recognized his smile, and realized this bearded biker guy was Rod Rodriguez. What a happy shock! We spent a lot of time talking about art school and catching up.

Over the years, we kept in contact—at Bill Griffith and Diane Noomin's house when Arcade Comics was forming, at comics cons, and going for a few drives in his huge Buick with zebra seat covers. He became my touchstone, someone to confer with about comics and politics and always the days at art school. We laughed about having a Silvermine Guild alumni show: Spain, M.K. Brown and B. Kliban and we actually gave it a bit of thought.

The last time we talked, a month or so ago, I thanked him for sending his latest book, Cruisin' With the Hound. His inscription in the frontispiece was, "Hey, what are you doing in my book?" and my first reaction was, "Uh, oh." But it was a typically generous mention in his interview with Gary Groth. He was always encouraging and supportive to other artists.

He made characters like Fred Tooté and Fissure human. They were real and stylized at the same time. The element of danger was always there which sharpened the humor of the hoods fussing with their ducktails in store windows, grousing about food. He said he had lots more stories to tell from that time.

Before we said goodbye, I invited him to come out with Susan and Nora for lunch and a walk. He said he didn't walk much. He also said, "Susan takes good care of me." These comments made sense later, of course, when I realized how ill he was, something he never mentioned.

I'm grateful that this lovely man had a peaceful home with Susan and Nora, of whom he was so proud, and that we have his work to remind us of his spirit. But I sure hate to really say goodbye.

————————

Jay Kinney:

If I’m late with my tribute to Spain, it is largely due to my having been preoccupied with finishing off two of Spain’s art jobs that had been left uncompleted when he took to bed for the last week of his life. Both were on tight deadlines and Spain kept hoping he could complete them, but rather suddenly it became clear that he was just too ill to continue.

According to Spain’s wife Susan, I was the only artist he’d approve of to do the job, which was simultaneously a great honor and a nearly impossible and intimidating task. So I spent the weekend before and the two weekends after his death being, in effect, Spain’s ghost.

The only way I could cope with what amounted to severe stage fright was to perform a kind of mind-meld with Spain and just barrel on through, working at a pace that allowed very little looking back. It was an oddly intimate way to mourn his departure, and one side effect was that it postponed it from really sinking in. Only now am I beginning to fully feel the enormous gap that he’s left behind.

I first met Spain in the fall of 1969 at the offices of the East Village Other on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. I’d just transferred to Pratt Institute from a small college in Ohio, and at the top of my list of priorities was meeting the EVO cartoonists, who were already legendary, as far as I was concerned. I took the subway from Brooklyn to the Astor Place stop, walked the block and a half to EVO’s offices above the old Fillmore East, and asked after Spain. “Oh yeah, he’s in the darkroom,” someone told me, so I penetrated that spooky space, lit only by a dim red light, and gave him my greetings. He was at the tail end of developing a Photostat and told me he’d be out in a minute or two.

When he emerged, I was confronted by an imposing figure clad in his Road Vultures colors, looking for all the world like Trashman minus the trench coat. He was gruff, but friendly, knew my work from Bijou Funnies and the Gothic Blimp Works, and gestured over at the shelves of EVO back issues and graciously told me to take what I wanted. I subsequently hauled an enormous stack of tabloids back to my art school dorm room, and reveled in all the comix that Spain, Kim Deitch, and Trina had drawn for the paper. Alas, I only saw the EVO artists a time or two that fall before they pulled up stakes and drove ’cross country to San Francisco to join the burgeoning underground comix scene. I followed the migration in 1972 and have had the privilege of friendship with Spain ever since.

I always felt that Spain was like the older brother I never had, and as the years went by, I thought of him as my best friend. I’m not sure how many others shared that notion, but he was certainly a loyal and enthusiastic friend to many of us. As a cartoonist, I earned his respect, in part, by being able to draw “good looking chicks.” Even after I largely left cartooning behind to concentrate on editing and writing, he was still supportive of my work, and there was no diminishment in our friendship.

Spain’s work ethic was second to none. He loved to draw and it’s fair to say that he lived to draw. Every time I’d stop by his place, he’d be working on a new comic story or poster or illustration job. In my opinion, he was woefully underpaid for most of these, but he was so prolific and hard-working that he somehow managed to make a living at what he loved most.

We once decided to collaborate on a story for Young Lust #7 (1990), “Slave of Ishtar”, a puckish meditation on our forays together over to the Mitchell Brothers’ Theatre, where we got to do ample “research” on female anatomy, strictly for Art’s sake, mind you. But I soon discovered that collaborating with Spain was not an easy task.

While I had envisioned inking Spain’s penciling and him inking mine, I discovered that Spain didn’t really do pencils. He did the roughest of sketchy penciling and then did all the tight detailing as he inked. His art was all in his head — full-blown — and I was mostly relegated to co-authoring the story, lettering it, pacing and layouts, and some background detailing. Spain had no problem working from others’ scripts or layouts, but his real pleasure was in carving out his stylish universe with pen and brush. In the end, it was difficult to distinguish between our collaborative strip and a solo Spain strip. Spain’s artistic vision was constant, unwavering, and dominant. Imagine trying to collaborate with Niagara Falls, and you’ll get the picture.

Spain was, when all was said and done, an unrepentant Stalinist who believed in the need for “strong leaders” in revolutionary situations. At the same time, he was not dogmatic about it and was open-minded toward competing left currents, particularly anarchism. When I came up with the idea for Anarchy Comics c. 1978, he was a strong supporter of the project and perhaps the most consistent mainstay of the comix series.

When Anarchy Comics: The Complete Collection (PM Press) finally came out this late fall, the publisher brought over printed copies on Nov. 28th. My first impulse was to rush a copy over to Spain, by now confined to his bed. It was only then that I found out that he’d died that same morning at 7 AM.

So long, my brother. We’re all missing you, like you can’t believe. It was an honor and a privilege to have you as a friend. If, by some fluke, there is an afterlife, I fully expect to see you again, still drawing comics for the underground press in Heaven, and still challenging God to strike you down if He really exists.