Born March 2, 1940 in Buffalo, New York

Died November 28, 2012 in San Francisco, California

Spain Rodriguez brought a unique perspective to comic art – a hard-edged outlaw’s attitude coupled with a voluptuous sensuality that also espoused class struggle and a universal quest for human dignity. His characters were die-hard individuals who ceaselessly fought the oppressor, powerful women who demanded respect – by force if necessary, and many of the real people who inhabited his life. He excelled at science fiction fantasy, gender warfare, heroic tall tales, and the dramatization of his own experiences. He also created many non-fiction works on historical figures and events, including Joseph Stalin, Che Guevara, and Lily Litvak, the Rose of Stalingrad. He was a genuine Marxist who fought fairly and with club spirit.

He had a lot of stories left to tell, he said in a recent interview for his autobiographical collection, Cruisin’ With the Hound.

“If I live long enough, I’ll do stuff about other periods, like here in San Francisco when I first got here and on the Lower East Side. They were replete with many adventures.”

Now it’s too late. Those stories went with him.

He was born and raised in Buffalo, a blue-collar city in upstate New York, where his colorful and formative upbringing provided a wealth of anecdotes and legends for his later comic stories. He picked up the nickname Spain at around 12 years old, when he heard some kids in the neighborhood bragging about their Irish ancestry. He defiantly claimed Spain was just as good as Ireland, so they began calling him that. It stuck.

“When I was a kid I wanted to be an underground cartoonist. Whatever that was. I would draw pictures of American airplanes having a dogfight with the Japs. He would say, ‘you son of a bitch.’ This was when I was about 11 or 12. That was racy stuff back then. My parents made me get rid of that one. My early forays into learning how to draw the female body came from copying Rulah of the Jungle.”

He attended Silvermine Guild School of Art for three years, punched a time clock at the Western Electric plant for five more, and rode with the Road Vultures Motorcycle Club on his own time. His artwork caught the eye of the red squad in the Buffalo police department when they discovered a mural drawn on the wall of a friend’s apartment showing cops getting run over by motorcycles and a naked Lady Bird Johnson.

He created one of the first major comic works in the nascent underground press in 1967 with the 24-page, tabloid-sized Zodiac Mindwarp, and became a staff cartoonist for the East Village Other, where he introduced Trashman, Agent of the Sixth International, an urban guerilla warrior, and designed many covers and editorial illustrations for the weekly paper.

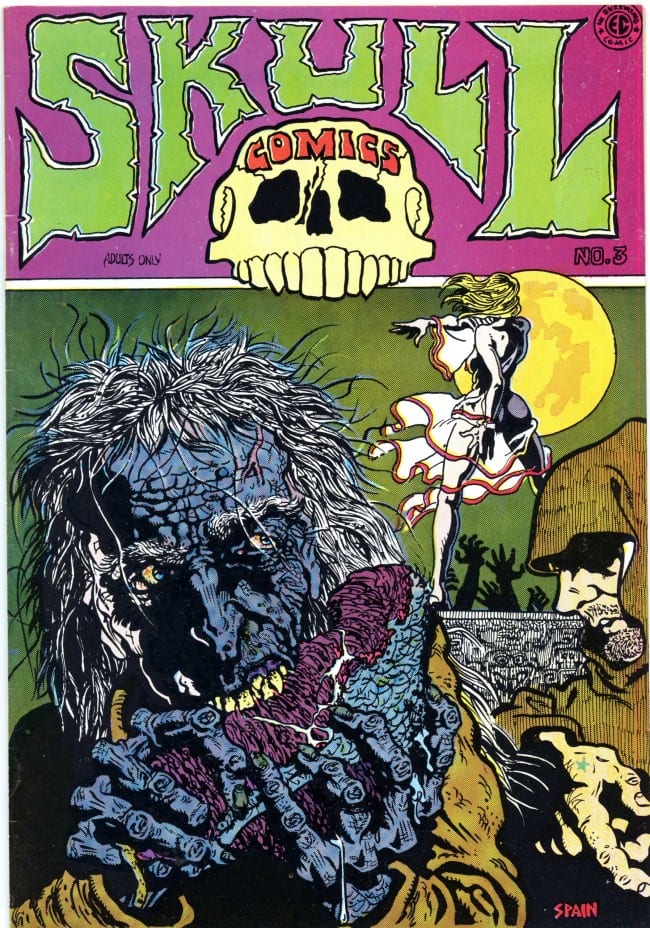

He moved to San Francisco in 1969, ground zero for the underground comix movement when he was invited into the Zap Comix Collective by Robert Crumb. He continued the saga of his best-known character, Trashman in three issues of Subvert Comics, edited three issues of Insect Fear Comics and contributed to many other underground titles during the peak years of that era, including Skull, Mean Bitch Thrills, Sleazy Scandals of the Silver Screen, Thrilling Murder, San Francisco Comic Book, and Young Lust.

He drew an eight-page story about rumbling and riding with the Road Vultures Motorcycle Club for Zap #6 in 1973. “’Evening at the Country Club, which was the first Road Vultures story was a breakthrough for me. Right, that I was able to tap into my own life and use that as a source for inspiration.” He continued to illustrate RVMC adventures in Zap and Blab! and collected many of them in the 1994 compilation My True Story.

The usual suspects often criticized him for his depiction of violence and sexual activity, but he didn’t really care. “I’m just a crude dude in a lewd mood,” he would reply. Comics were his chosen medium of expression and he wielded his pen and brush with impunity.

The usual suspects often criticized him for his depiction of violence and sexual activity, but he didn’t really care. “I’m just a crude dude in a lewd mood,” he would reply. Comics were his chosen medium of expression and he wielded his pen and brush with impunity.

“It seems to refer to the core of the American vision or the democratic vision, that there’s an aspect of yourself that you owe to your society in terms of omission and commission, but there’s an aspect of your life that you don’t owe to anybody. This is something that there’s a constant fight over. In terms of underground comix they certainly broke through that fifties fantasy that conservatives are so dedicated to maintaining, despite that fact that it was a fantasy in the fifties, and now it’s an absurd charade. Comic books are really something that are part of some core of this country. And that’s the struggle. Liberty and justice for all should mean you can say what you want. Unless you can show some tangible harm I’m doing to somebody, fuck off. That’s the battle line I want to be on. I intend to remain here until they carry me away on my back. If it doesn’t sound too grandiose, I think the undergrounds were really a continuation of the American Revolution. Hell, it sounds too grandiose, but so what?”

A longtime resident of San Francisco, Spain actively participated in a variety of artistic causes and political action groups, including the Cartoon Workers of America, San Francisco Mime Troupe, and other grassroots organizations, as well as teaching comic art to school children in the Mission District. He also created posters, murals, rubber stamps, skateboard decals, movie sets, record albums and inaugurated one of the earliest on-line comic experiments, Dark Hotel for Salon magazine.

He drew covers and illustrated many books, including Boots, Alien Apocalypse 2006, Sherlock Holmes’ Strangest Cases, Nightmare Alley, Che: A Graphic Biography, and Yiddishkeit: Jewish Vernacular and the New Land.

He was recently honored with a lifetime retrospective art show at Buffalo State College’s Burchfield Penny Art Center, Spain: Rock Roll Rumbles Rebels & Revolution. It was a struggle for him to attend the event since he was weakened by his ongoing battle with cancer but it brought him a lot of satisfaction to see his whole career fully displayed in the place where it all began. It gave him hope that his work would continue to be read and appreciated by future fans.

“I get satisfaction knowing that stuff is going to be out there. Ramses the Second built these four gigantic statues to himself. One of the faces is still intact. The impulse of art is the impulse of immortality, just like those guys in the caves. At some point it must have occurred to them this stuff is going to be around. Today we have a different strategy. We can’t call upon the resources of the state to tell our tale. You do these highly vulnerable books on this paper that’s prone to rot and you hope that in time some of these will survive. You have these periods in history of outbursts of creativity and people telling the tales that would otherwise not be told. This is a factor. I think as it goes out there, somebody is going to hang onto this stuff. Someone is going to say, this is great.”

I visited Spain at his home in October. He had a doctor’s appointment that morning for another round of treatment that gave him a lot of discomfort, but he was in good spirits. He and his wife Susan and I sat around their kitchen table and had coffee and tea with scones. I asked if I could take a photo with him so we went downstairs to his unfinished wall mural and shot a few. They offered me a lift and dropped me off at 16th and Mission where we said goodbye. I’m glad I got to see him one last time. I greatly admired him as a person and an artist. He was ruthless to his enemies but generous and considerate with people he liked.

“I’ve enjoyed immensely being a Zap artist. I’ve enjoyed being an underground cartoonist. I generally wish everybody well.” - Spain Rodriguez, 2012

Spain and his fellow Zap artists Robert Crumb, Paul Mavrides, Victor Moscoso and S. Clay Wilson meet to work on the jam "Important Comics" for Zap #14 in 1998. Photo by Rebecca Gwyn Wilson.