It's my general policy not to comment on the textual front and back matter of comic strip collections, though it often irritates me. In the first place, next to nobody reads it. In the second place, for those few who do read it, it has next to no potential to spoil the book. You're reading the book for comics. The supplemental material might slightly enhance the experience, but if not it's merely forgotten. It is at most an appetizer, and most of the time I leave it for last lest it spoil my appetite. However, I found Thomas Andrae's hors d'oeuvre to Walt Kelly's Pogo The Complete Dell Comics: Volume One (Hermes Press) went down so poorly that I feel the need for a belch.

The analysis of racist content is to our chagrin a necessary component of writing about old comics. In interrogating this particular text Andrae has adopted the maximalist standard that can condemn a work that materially advanced the abolition of slavery as racist. You want to ask these people that if Harriet Beecher Stowe was being racist when she sentimentalized Uncle Tom, what was Charles Dickens doing when he sentimentalized Little Nell and Tiny Tim? Or you would if you were writing about Uncle Tom's Cabin. As applied to Walt Kelly by Thomas Andrae these standards yield conclusions that are completely wrongheaded.

At the outset, we must presume that Walt Kelly was more enlightened than Thomas Andrae, or you, or me. This is because unlike Walt Kelly's, our enlightenment is socially assisted. Walt Kelly had to come upon his all on his own. Now, any of us might have been one of the enlightened people in those days, and all of us think we would have been one of the enlightened persons in those days, but the odds say otherwise, and in the actual event Kelly was. We simply embrace the conventional wisdom of our time. Kelly swam against the tide. To have a non-stereotypical black child as the identification character of a comic strip was practically unheard of. This was Bumbazine, who initially played a kind of Christopher Robin role among Kelly's creatures of the swamp. For our hanging judge, however, being sui generis is not nearly enough.

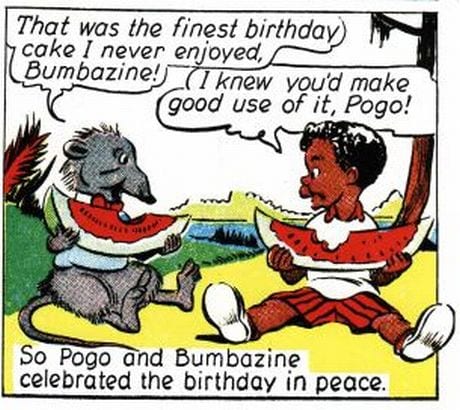

While Andrae does acknowledge Kelly's enlightened tendencies, this knowledge doesn't lead him to anything like generosity. Bumbazine is, according to Andrae, "a regular boy in some panels but in others he had bulging lips and saucer eyes, and he spoke in rural Southern dialect like the animals, reinforcing reductionist images of blacks as uneducated and intellectually inferior." This is simply false. While Bumbazine's lips will at time tend to the liverish, he is invariably well-dressed and is the most well-spoken character anywhere in the strip. Andrae goes on, "in the last panel of Animal Comics #1 he drew Bumbazine and Pogo celebrating Pogo's birthday by gleefully eating large slices of watermelon, recycling the racist imagery of Little Black Sambo and other black stereotypes." Leaving aside that Little Black Sambo is not set in the United States but in India, does not involve anyone of African descent, and does not employ any stereotypes involving watermelon, this is still a complete misrepresentation of Kelly's story. Rather than a tale of depraved watermelon-mongering, it is the story of how Bumbazine spends the whole day trying to bake Pogo a birthday cake and keep it out of the hands of Albert the Alligator. In the end, after the heavy confection has dragged Albert to the bottom of the swamp, thus getting him out of the way, Pogo and Bumbazine settle down to the simpler pleasures of watermelon, which doesn't require preparation. Bear witness to this scene of racist horror:

This is ultimately a failure to understand what the watermelon stereotype actually entails. Surely you realize that there's nothing intrinsically degrading in liking to eat watermelon. Watermelon was one of the props in a general stereotype of the African American as filled with infantile enthusiasm, easily distracted and reduced to paroxysms of delight at the rattling of dice, the smell of fried chicken, or the sight of a watermelon. This is not what's happening in Kelly's story at all. But then, Andrae hardly seems to have an idea of his own on this subject at all. Rather, he has a grab bag of received notions, incompletely understood and haphazardly applied. Watermelon equals racism, that is all you know and all you need to know.

This is ultimately a failure to understand what the watermelon stereotype actually entails. Surely you realize that there's nothing intrinsically degrading in liking to eat watermelon. Watermelon was one of the props in a general stereotype of the African American as filled with infantile enthusiasm, easily distracted and reduced to paroxysms of delight at the rattling of dice, the smell of fried chicken, or the sight of a watermelon. This is not what's happening in Kelly's story at all. But then, Andrae hardly seems to have an idea of his own on this subject at all. Rather, he has a grab bag of received notions, incompletely understood and haphazardly applied. Watermelon equals racism, that is all you know and all you need to know.

Andrae is on firmer ground in denouncing the characterizations in the story from Animal Comics #5. Once again, however, he is sloppy in characterizing them as "derisive minstrelsy stereotypes." The conventions of the minstrel show were as formalized as the Harlequinade, and the characters in the story at hand don't fit them. Further, I believe a more sophisticated and context-conscious reading would come to a different conclusion. Feeling ostracized after having once again ruined everyone's good time, Albert leaves the swamp and finds himself in what must be the little railroad town Bumbazine comes from. Andrae can see this town as nothing but a plague of derogatory stereotypes. In this he fails to see the forest for the trees. In popular entertainment the African American had only one role -- a menial one. A maid, a janitor, a porter, a shoeshine boy -- these are the positions they are fit for, while the whites do all the important work. In Kelly's little swampside town black people fill every role -- the station master, the ticket taker, the engineer of the train, which they get to ride. The only white people pictured are a couple of hillbilly layabouts getting drunk under a tree. This is all nearly as unheard of at the time as, well, a comic strip with an unstereotyped black boy as a reader identification character.

Andrae's hanging judge predilections oversimplify a vexed and complicated question: Where is the line between a humorous depiction and a merely derogatory one? To my mind there are some basic questions to ask in determining this. Is there any malice in the depiction of the characters? Are the characters primarily held up to ridicule? Is the pleasure the work affords in large part a feeling of superiority? When you're talking about black characters in a vintage comic strip, does the cartoonist abandon his normal style for a simplified golliwog treatment, as you would see for example in Wash Tubbs or Moon Mullins?

On the last point I would say that you can give Kelly a clean bill. Each character is depicted with care and individuality, and without any malice that I can see. In the story Albert leaves the swamp hoping to be better appreciated in civilization. After being initially startled by this huge predator in their midst, the townspeople soon realize the commercial potential of a talking alligator, and begin to fight amongst themselves over who has the right to this bounty. Albert takes the opportunity steal the train and make his escape after a slapstick chase. Could this be taken as ridicule of the townspeople, and intended to make the reader feel superior? Well, you could take it that way, and Thomas Andrae does, but to me it seems like he's treating the black characters the same way as he does every other character. He considers them human enough to represent humanity.

As Andrae acknowledges, though not in such a way as to give the man much credit, Kelly himself came to the conclusion that the well had become so poisoned with derogatory images that he couldn't treat black characters without being taken the wrong way. To be beyond the possibility of misinterpretation requires not equal treatment but overcompensation, a condition under which humor can't exist. Once Bumbazine makes his exit no character openly suggestive of African descent will be seen in Pogo again. Mazel tov.

The railway sequence was merely one example of the restless experimentation that marked the early years of the strip. Pogo had an extraordinarily long period of gestation. The first story appears at the end of 1942 and the character designs are still evolving in the first year or so of the comic strip seven years later. Indeed, comparing the covers with the rather slapdash art of the stories you have to wonder if working in comic books impeded his development. The Complete Dell Comics is thus more for the Kelly aficionado than the general reader. Aside from losing the first two pages of one story to a production error, the effect is generally pleasing. This being Hermes Press the stock is coated, but the gloss in unobtrusive, and the stories are reproduced in near-publication size, with every corresponding cover, by Kelly or not. Even the error is inadvertently revealing. It illustrates that by the third page of these stories the plot premise is undetectable, and all has descended into anarchy.

Initially, not-yet-Pogo models itself after the tales of Uncle Remus with a side order of A.A. Milne -- the misspelled signage is more Milne-and-Shepard than Harris-and-Frost -- and the first two years is a process of shedding the parts of those influences that don't look like Walt Kelly. First to go was Albert as a Br'er Fox-style villain, and along with that characterization goes the attempt to emulate A.B. Frost and his naturalistic animal characterizations. It's in the railroad town story that he truly begins to look like himself. Soon after he discards fable structure for minimal structure, and then comes to realize that human characters are superfluous his true identification character is Pogo. By the ninth installment Bumbazine is a mere walk-on and by the tenth he has walked off. From Uncle Remus he retains the dialect, and the trackless swamp remains a cousin of the Hundred Acre Wood, but his subject is the absurd dimension of the human character. The last story in Volume One is from 1947, two years before the debut of the newspaper strip, and at least some version of the main characters who Kelly would follow to the end are in place.

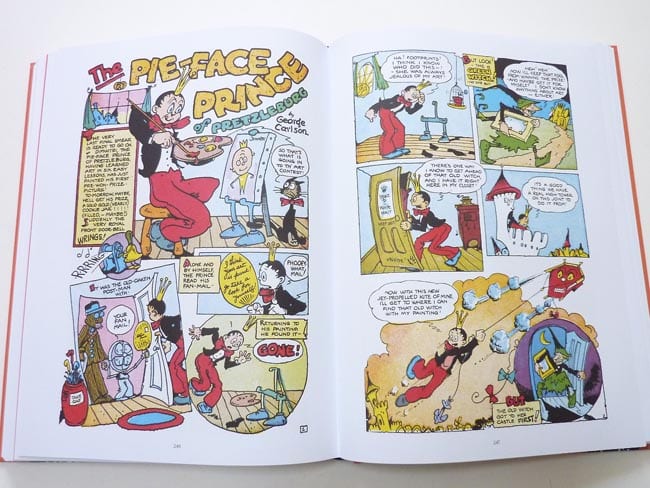

As showcased in Perfect Nonsense (Fantagraphics) George Carlson shows himself to be the missing link between Lyonel Feininger and Dr. Seuss. He was not the sort of cartoonist who was broadly influential, but the sort whose work was known to a relative few and remembered by all of them. He first makes his mark in John Martin's Book, a children's magazine for the carriage trade, some of which probably still owned carriages when it began publishing in 1913.

Carlson and his editor/collaborator John Martin were following in the footsteps of L. Frank Baum in seeking to create a uniquely American children's literature. They were collectively in rebellion against the traditional fairy tale/folk tale that formed the core of traditional children's literature. The European folk tale was escapist literature for people who had no escape. It thrived in an era of hereditary rank on a race memory that once upon a time, a common man could be lifted above his station in return for doing a service for the king. This form of imaginary upward mobility had no appeal for the entrepreneurs and go-getters of the Progressive era United States. (Recall that before the eminently practical dreamer Baum created Oz he edited a magazine for store window dressers.) Martin and Carlson's brand of children's literature eschewed moralizing and pursued education, always sweetened with pure entertainment in the form of nonsense. The strongest material in Perfect Nonsense are the comical abecedaries and verse features, written by both Martin and Carlson, which retain a remarkable freshness and bite.

As I browsed through the book, though, I found the most engaging aspect of Carlson's cartooning was its antiquated feeling. I spent a long time trying to find a way to define this quality when the right word hit me: Pre-Disney. It was ultimately Walt Disney who would not only succeed in defining the uniquely American form of children's literature, but would remake it into children's entertainment. Disney and movie animation generally would transport the imaginative world of children away from the medieval kingdom and the ancient forest to the barnyard and the big city, and most decisively into the present. Its voice would be the voice of the country bumpkin and the city slicker, the hillbilly and the cowboy, the wiseguy and the stumblebum. Even when it would venture into the world of the traditional fairy tale it would be stripped of the grotesque and the gothic, and told in American English as spoken by immigrants. Its appeal was decidedly to the streetcar trade; Woolworth's, not Wanamaker's.

As I browsed through the book, though, I found the most engaging aspect of Carlson's cartooning was its antiquated feeling. I spent a long time trying to find a way to define this quality when the right word hit me: Pre-Disney. It was ultimately Walt Disney who would not only succeed in defining the uniquely American form of children's literature, but would remake it into children's entertainment. Disney and movie animation generally would transport the imaginative world of children away from the medieval kingdom and the ancient forest to the barnyard and the big city, and most decisively into the present. Its voice would be the voice of the country bumpkin and the city slicker, the hillbilly and the cowboy, the wiseguy and the stumblebum. Even when it would venture into the world of the traditional fairy tale it would be stripped of the grotesque and the gothic, and told in American English as spoken by immigrants. Its appeal was decidedly to the streetcar trade; Woolworth's, not Wanamaker's.

The house style of Disney would be the look of children's entertainment, not only because Disney was so popular but also because a great deal of the drawing would be done by moonlighting Disneyites. Or Disney refugees like Walt Kelly. The development of his mature style is practically a journey back to the ways of Disney. The evolution of Pogo looks like nothing so much as the development of Jiminy Cricket. When Ward Kimball started to design Jiminy he found that anything that looked like an actual cricket would be rather awful, and the character ultimately saw the light of celluloid as a little man with a grasshopper head. Kelly initially modeled Pogo on the opossum, a creature that makes a rat look friendly, and eventually wound up with a bipedal puppy.

George Carlson takes us back to a visual environment where Disney doesn't exist, and thus his work has the fascination of the unfamiliar. Nor would his work ever be contaminated by the Post-Disney idiom. It evokes olden times rather than embracing the present. Particularly in the John Martin's Book portions it is an environment where children are well-dressed and well-behaved, in contrast to the animated cartoon which embraces misbehavior, even if order is restored in the end.

Reading the selections from Jingle Jangle Tales leaves me with the same mixed feelings I've had from earlier fragmentary reprints: Disappointed that a more complete collection doesn't exist while suspecting that once you've seen one you've seen them all. Carlson had neither the satirical impulse of Baum or Lewis Carroll nor the feel for character of a Walt Kelly. They have some of the growl of the Simplicissimus cartoonists but not the bite. Like Edward Lear, his nonsense is satisfied with being nonsensical. Still, I'll be one the first in line for a complete collection when it comes out.

When I first encountered her work in the National Lampoon my reaction to M.K. Brown was a mild irritation, arising I think from a failed attempt to get it. It wasn't until I encountered it again in Rick Meyerowitz's National Lampoon anthology Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead that I realized what an extraordinary cartoonist she is. Thus the career retrospective Stranger Than Life (Fantagraphics) was something I've been anticipating like Christmas. When she submits to the constraints of less indulgent markets her work is merely funny, but when allowed to roam free her mind was clearly getting telegrams in code from the same people who used to communicate with George Herriman. Like Herriman she was fortunate to find a venue that would give her free rein. Its hard to imagine if she could have thrived if there had not been a magazine like the National Lampoon that would adopt as a credo "Making people laugh is the lowest form of humor." Perhaps the essence of her humor is encapsulated in the following cartoon:

What my deficiently imaginative younger self failed to realize is that there's nothing to "get" here. There is absolutely nothing that can be called a joke. The humor is in the absolute otherworldliness of this character, and that she or he or it would claim regular existence on this plain of being at all. It is a living emanation of forgotten advertising art come to life.

Even if it wasn't one of those rare books where the writer of the afterword denounces the work of the writer of the foreword, Stranger Than Life would be guaranteed to be unlike anything else on your bookshelf, where it ought to be.

My earliest memory of a particular comic strip comes from when my grandparents came back from a visit to the Old Country, which is to say New York City, with a copy one of the New York Sunday papers. I don't know which, but whatever one had Terry and the Pirates, that's what it was. I'd never seen a comic strip that looked so grim and foreboding; I don't think the Los Angeles papers even had ink that dark. Other than that impression the only specific thing I recall is that endlessly intriguing title -- who the hell was Terry and weren't pirates those guys with cutlasses and parrots on ships in the olden days? I didn't know from Milton Caniff or George Wunder or any cartoonist except for maybe Charles Schulz, but it must have been Wunder's Terry I was looking at.

I have a general disdain for zombie strips, but I have always wondered about Wunder. I was mildly intrigued by the fragmentary examples of his work I'd seen here and there, and the way he made his characters look like depraved marionettes. I had gotten the impression that Wunder was an even more dedicated Cold Warrior than Caniff, but I honestly don't recall where I'd gotten that impression and I've been mildly interested in testing it. Terry and the Pirates: The George Wunder Years Volume One (Hermes Press) was an opportunity to satisfy one of those curiosities. As this volume ends in 1948, before Mao took power in China and things began to look really dire, Terry and company are on their way to give the White Man's Burden a test hoist in the still-French Indochina. It's Hermes Press, so once again with the coated stock, which once again doesn't spoil it for me, though I would say that on the color pages particularly the feeling is more like looking at a photograph of a comic strip than a comic strip. The book design could be charitably described as undistinguished (did I say it was Hermes Press?) but it is an agreeably wide-screen experience. It would be nice to see the Caniff Terry at this size.

I have a general disdain for zombie strips, but I have always wondered about Wunder. I was mildly intrigued by the fragmentary examples of his work I'd seen here and there, and the way he made his characters look like depraved marionettes. I had gotten the impression that Wunder was an even more dedicated Cold Warrior than Caniff, but I honestly don't recall where I'd gotten that impression and I've been mildly interested in testing it. Terry and the Pirates: The George Wunder Years Volume One (Hermes Press) was an opportunity to satisfy one of those curiosities. As this volume ends in 1948, before Mao took power in China and things began to look really dire, Terry and company are on their way to give the White Man's Burden a test hoist in the still-French Indochina. It's Hermes Press, so once again with the coated stock, which once again doesn't spoil it for me, though I would say that on the color pages particularly the feeling is more like looking at a photograph of a comic strip than a comic strip. The book design could be charitably described as undistinguished (did I say it was Hermes Press?) but it is an agreeably wide-screen experience. It would be nice to see the Caniff Terry at this size.

To my mind the question is not so much is it worth preserving as, should we let it go to waste? I don't know how many volumes beyond this I'd like to go but I didn't feel it was time wasted. When you endeavor to take over a successful strip rather than creating your own you're looking for a sinecure, not self expression. Still, Wunder handles it like a seasoned professional. It bears the same relationship to Caniff's strip as Beatlemania has to the Beatles, but the fringe benefit to that it retains the theme of freebooting soldiers of fortune in exotic places. Efforts are made to bring the pre-war band back together, which must have seemed a little odd at the time since Caniff had just made the grand tour of all his old mainstays before he left. Connie doesn't come back because even in 1946 you couldn't get away with that shit anymore, but Big Stoop has a cameo. Pat Ryan comes back, who I always liked better than grown-up Terry Lee, but only long enough to demonstrate that with a grown-up Terry Lee fronting the strip there's nothing for him to do. And of course the Dragon Lady is on the cover.

Wunder's Terry made me want to remind myself why I'd stopped reading Steve Canyon before Kitchen Sink stopped sending me review copies, so I pulled down Damma Exile, the 25th volume in the Kitchen Sink Press Steve Canyon series (including magazine format issues), whose cover I'd never cracked before. The first thing I notice is, sure Wunder is okay, but in comparison Caniff is the cartoonist from Planet Krypton. The eyes of all his characters are alive where Wunder eyes suggest taxidermy. The second thing I notice is that by this time (a couple of years past the most recent Library of American Comics installment) it has ceased to be an adventure strip. In a short, informative introduction Pete Poplaski informs us that the biggest hits of the time in the dramatic category were On Stage and The Heart of Juliet Jones. Caniff, now an owner and not just an employee, felt bound to take notice. He had also become intrigued with Little Orphan Annie. The first half of the book is taken up with a real Harold Gray plot: PoteetCanyon, Steve's orphaned cousin, is coaching the kids from the high school of the bedraggled mining town near Steve's Air Force base to make a bid in the state basketball championship. This goes on for months. It demonstrates mostly that Harold Gray's métier was not Caniff's. In the second half of the book there's something that's almost like international intrigue as the State Department sends Steve to thwart a privately funded Chinese Bay of Pigs invasion figureheaded by an exiled Asian princess whose fondest wish is not to liberate her country but to become an ordinary American housewife, and it all begins to seem like the finals of the World's Biggest Square contest.

It's a curious thing that when the disaffected youth of the 1960s tried to forge an identity they looked to the movies and pulp magazines and comic books that their disaffecting parents had created or consumed before World War II. I listen to the records those kids made and wonder if a younger generation had ever before been that young. I compare what their parents created before that war and what they created after it and wonder if there ever was an older generation that became that old.