What I find impressive about many of the recently emergent small-press and boutique publishers is their rate of output. Rather than just put out a book or two a year, some of them have been quadrupling that publishing rate, releasing three books per season. Some of them serve as a sort of regional publishing hub for talented local artists looking for support, while others scoop up talented younger artists who are either working digitally or via mini-comics. Let's take a look at some recent releases from a variety of these publishers.

Koyama Press

Anne Koyama is an indefatigable champion of young cartoonists and Canadian cartoonists who need a venue for publishing. Her taste as a publisher is all over the place, from the cute and cartoony work of Chris "Elio" Eliopolus to the morbidly droll cartooning of Michael DeForge. The latest set of comics that I've seen from Koyama is most definitely on the dense, poetic and even opaque side. The most approachable of the set is Jesse Jacobs' By This Shall You Know Him, a duo-tone work of myth in a vein similar to Jesse Moynihan's Forming. Unlike the latter work, which explains a highly complicated series of origin myths for the planet Earth as essentially a by-product of alien trade wars, Jacobs' comic posits life on Earth as the result of a sort of aesthetics contest held by a group of higher beings.

Like Moynihan's work, this comic is earthy, visceral, occasionally bawdy, and frequently disgusting. The higher beings are often petty, obtuse, and easily amused, as the rivalry between gentle Ablavar and prickly Zantek (both of whom have a certain Kirby-esque touch in their character design, especially Zantek, who looks like Arnim Zola the Bio-Fanatic) turns into a deadly and tragic affair. Ablavar's desire to keep the earth nice and cuddly with his animals is subverted by Zantek's creation of mankind, though his Adam is a grunting, defecating simpleton. There's a lot of self-consciously "cosmic" imagery in this comic, reflecting a kind of navel-gazing on the part of the godlike beings that manifests in intricate, dense patterns of small blocks and interlocking shapes. These interludes serve no purpose in the narrative other than to get the reader to slow down, reflect, and look at the world in the way its characters might. The comic plays out with a couple of twists, as the identity of the First Murderer is a surprise though the overall fall of the reign of animals and the ascendancy of man (here played as a tragedy) are both inevitable.

Tin Can Forest's (aka Pat Shewchuk and Marek Colek) Wax Cross is a far more difficult comic to parse. There is no question, however, that this fable is astonishingly beautiful and visually exciting in a different way in each of its twelve two-page chapters. It's a classic fairy tale journey across time, place and concepts, reaching deep into the past with its tropes of witches and monsters but touching on the present and future with its references to electricity, technology, devastation, pollution and ruin. Visually, the chapters' styles range from photorealism to children's book illustrations to mimicked stained glass and various points in-between. The colors are rich but muted, as though the book was being viewed on an ancient newsreel or perhaps was found as an ancient artifact. The look of the book is actually a bit on the Fauvist side, with a preponderance of sharp lines containing the widely varied color schemes. The sixth chapter contains some of those photorealist images, except they mimic old, washed-out photos, or perhaps the strange light one sees during twilight, reminiscent of certain Al Columbia comics. The eleventh chapter is notable because it's entirely devoid of color, as this chapter about death takes place in a dreamy, wintry world. Wax Cross feels as much like an incantation as a narrative; it's a looping, recursive journey that begins with a prayer against the ills of the post-apocalyptic world (radiation, disease, poison) that seems to be as much for the reader as it is for its narrator-protagonist. It's a book that rewards multiple readings.

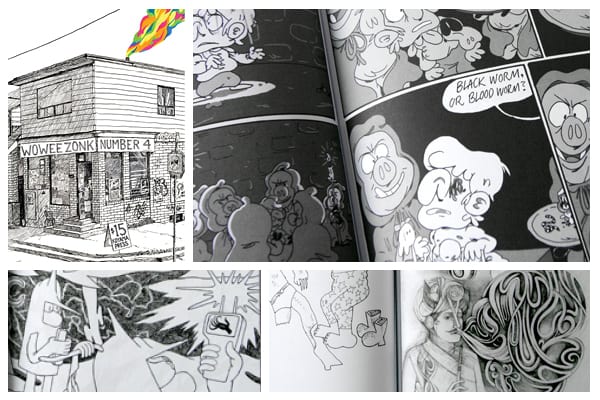

Koyama is also providing a home for pre-existing series like the anthology Wowee Zonk, whose fourth issue is the biggest and most ambitious ever for this series. It's sort of Canada's answer to Kramer's Ergot: an anthology with widely varied, personal, and idiosyncratic material that often skates on the borders of narrative. Edited by Ginette LaPalme, Chris Kuzma, and Patrick Kyle, Wowee Zonk features artists who were mostly unfamiliar to me in terms of name but quite familiar in terms of approach. Donald Dixon, Benjamin Hettinga, and Mark Connery's strips are all variations of Gary Panter by way of Ben Jones: crude but expressive images, frequently dopey gags punctuated by the power of the individual images, and a kind of hyperstylized & nonsensical use of language. Kyle's work is more in the vein of trippy, Fort Thunder-esque adventure comics that emphasize movement and exploration, while LaPalme's story is more elliptical and delicate, immersing the reader in her poetic worldview.

Ryan Dodgson's crisply-drawn geometric shapes interacting in the space of a panel remind me a bit rhythmically of John Hankiewicz's comics. One of the sharper juxtapositions in the book comes toward the end, when stories by Adam Buttrick, Connery, and Andrei Georgescu come right in a row. Buttrick's cartoony and big-nosed but viscerally gross and disturbing story has the same sort of effect in Wowee Zonk as a Josh Simmons story might in Kramer's; it is immediately followed by Connery's silliness, including a story where he basically dumps on his own comics when he fishes for compliments at a copy store ("Almost as good as Matthew Thurber?"), only to be told, "This shit is no 1-800-MICE." Following that with Georgescu's feathery and detailed pencils in a silent, abstract story that then turns into something that looks like it was drawn by computer completes this sort of whipcrack transition that this anthology does so well. Peppering in a very funny two-pager by up-and-coming cartoonist Alex Schubert and ending it with a visually striking, rubbery adventure story by Kuzma sort of recapitulates the book as a whole. The editors trot out a line-up that makes a big impression on nearly every page. That's what makes an anthology a success.

Finally, I wanted to mention Cereal, a minicomic by Brian Fukushima. A boutique publisher has the leeway to release books in a variety of formats, especially if their goal isn't to penetrate the bookstore market or get picked up by Diamond. If they're willing to find other models and methods to sell their books (conventions, internet, word-of-mouth, etc.), that means a publisher like Koyama can publish pamphlet comics like DeForge's or minicomics like Dustin Harbin's or Brian Fukushima's. This is a silly diversion of a comic about a cartoon tiger who desperately wants to try cereal, but is thwarted at every turn. The attraction here is the clean and cute cartooning and thick lettering that's very much a part of the mini's overall effect.

Hic & Hoc

Located in New Jersey, Matt Moses' small-press concern Hic & Hoc follows a model not unlike Secret Acres: seeking out cartoonists who are self-publishers and offering them a chance to work with someone who will do all the heavy lifting. Given his niche offerings, he publishes books, pamphlets, and even hand-bound collections of comics. Unlike Secret Acres, he specializes in publishing "transcendental joke books," a vague phrase that can be parsed through his first four offerings.

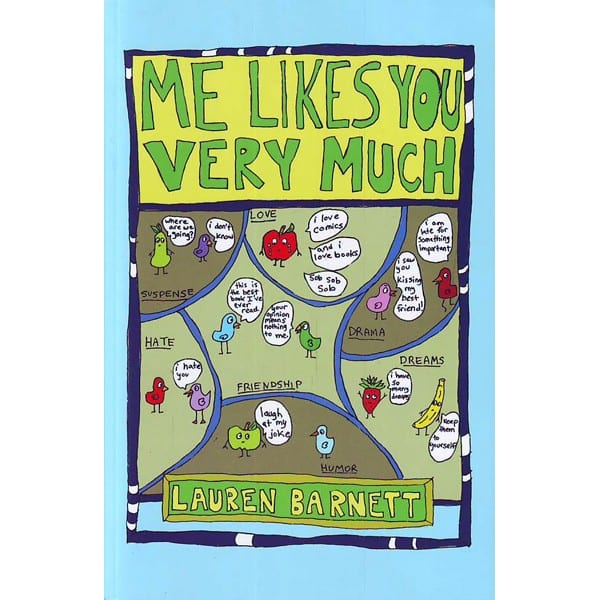

I blurbed Lauren Barnett's book with Hic & Hoc, Me Likes You Very Much, and I noted that "Barnett's comics are charming, self-deprecating and crudely enthusiastic. She has a particular talent for depicting both the absurd and quotidian, finding the essence of humor in both." Her crude drawings of anthropomorphic fruit and animals build in momentum the way that a stack of Sam Henderson gags might: getting funnier simply by virtue of having spent a great deal of time following the logic and language patterns of her dopey characters. This is the humor of non sequiturs and sheer absurdity. On the other hand, Neil "Neil Jam" Fitzpatrick's Everythingness is more on the "transcendental" end of things. Fitzpatrick is well-known to minicomics readers of the late '90s, thanks to his squat characters with huge black eyes. He's certainly become a more confident cartoonist since that time, refining his style to a smooth, clear, but cartoony array of navel-gazing characters. His comics have always felt twee, with his characters philosophizing in a fairly surface and obvious manner, and this book contains the same sort of fourth-wall breaking and musings about what it all means. Overall, this comic seemed to go over very familiar territory, both from an aesthetic and narrative standpoint.

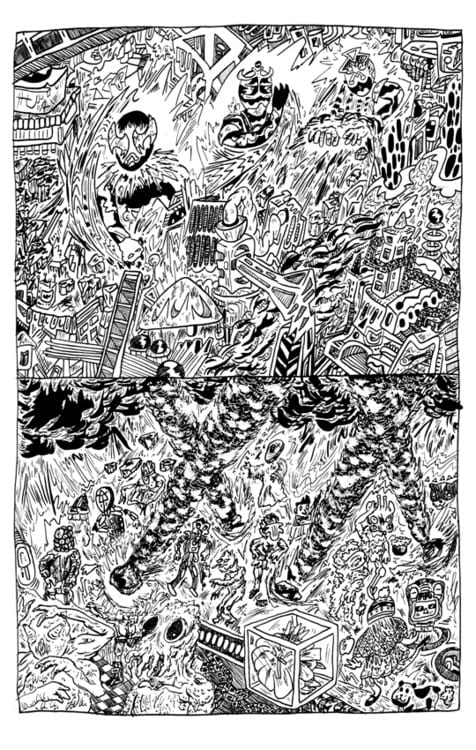

Speaking of familiar territory, Pat Aulisio's Bowman 2016 has one distinct advantage: the highly clever idea of imagining what would have happened if astronaut Dave Bowman (from 2001: A Space Odyssey) was stranded on a foreign world instead of becoming the Starchild? Aulisio's comics are practically a game of "spot the influence," as the Fort Thunder school, super-hero comics (especially Jack Kirby), and Michael DeForge's fusion ideas can all be seen here at various points, but there's a certain rollicking joyousness to this comic that makes it compelling on its own. Despite his influences, Aulisio at heart is a lowbrow artist cranking out something that's dumb, simple, and fun, even as his pages have that all-encompassing Mat Brinkman atmosphere, the frenetic nature of Brian Chippendale's scrawl, and the propulsive quality of a Brian Ralph comic. Aulisio isn't in the same league as any of these artists, but the low-fi nature of his work somehow works in a comic that's part parody, part cover version and part straightforward adventure.

The most interesting of Moses' first four offerings is Alabaster's The Complete Talamaroo. The grad of the School of Visual Arts hand-bound and silk-screened the covers of the 200 copies of this beautiful, weird little collection of minicomics. The title character is a catlike, naked, and stumpy female creature who romps about the forest, playing with bunnies, and looking for food. The art is cute but casual and not overly labored. What makes the book feel very different from something that could have gotten annoyingly twee is that there's a flock of birds who narrate the story through word balloons that appear as banners popping out of their mouths that trail them as they move. The birds urge Talamaroo to get up and kill something for food and berate her for failing at it, until she finally snaps and kills the narrators in a blind fury. It's a funny moment that's expanded upon in future chapters, where Talamaroo is tricked into taking a hallucinogenic mushroom by the birds, meets a male version of herself and gets jealous of another female of her kind when she appears on the scene. The birds are consistently the funniest and nastiest part of the book, as they initially think that Talamaroo and Talamarand (her male counterpart) are going to fight before they jump on each other and have sex. In the last story, a bunny friend of Talamaroo's uses a machine gun to kill the birds after they try to amp up her jealousy. Moses hit on a brand new talent here and has a chance to expose her to a slightly larger audience.

Moses will also be publishing new work by Dina Kelberman (an off-beat humorist whose weird style will fit in perfectly at Hic & Hoc), British cartoonist Philippa Rice, an anthology edited by the talented Emi Gennis, and a number of other projects. I like the fact that he's trying to provide a publishing space for alt-comics gag artists, humorists and other assorted and otherwise unclassifiable cartoonists. I have a sense that Moses' cartoonists will continue to largely fly under the radar, but I admire his commitment to keeping their work in the public eye and celebrating their eccentricities.

(continued)