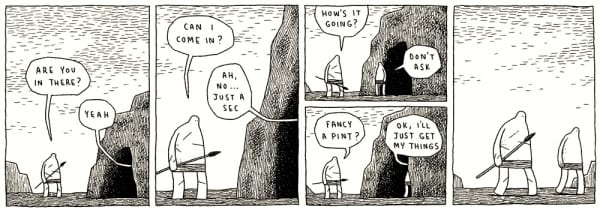

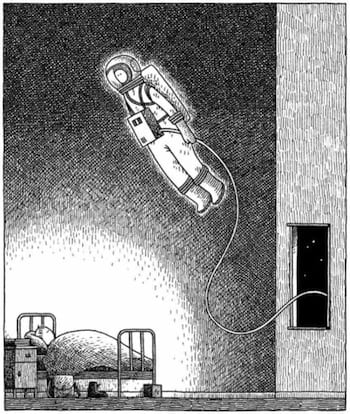

Nobody does silence like Tom Gauld. It sits heavy on his lonely lunar landscapes, dismantled robots and dilapidated moonbases; it pulls his tiny mute figures even further away from us as they wave proudly at the top of their doomed enterprises. Pages of perfectly paced silence make the few deadpan words he does use weightier, perfectly economised, no more or less than you’ll ever need. It isn’t just the absence of speech: Chris Ware does it too but it feels different, like the silence is in two different keys.

Gauld’s atmospheric world is bleak and lonely but totally funny and full of heart. He mixes heroic events and ideas with small human ordinariness: astronauts bickering on the moon, massive epic journeys in which nothing ever happens except conversations about lunch, and most recently a biblical giant doing the King’s bidding when he’d much rather be doing admin. His books are so human they make you like other humans. There are very few books I will give people and insist they read it on the spot, over dinner, while I sit there quietly monitoring their facial expressions. But Gauld's books ignite that kind of enthusiasm, and there’s something in them — a sweetness, maybe — that brings you closer to the guy on the train, the people on the street, makes you ache for more of that boring human ordinariness, our innate optimism, and all of our doomed enterprises.

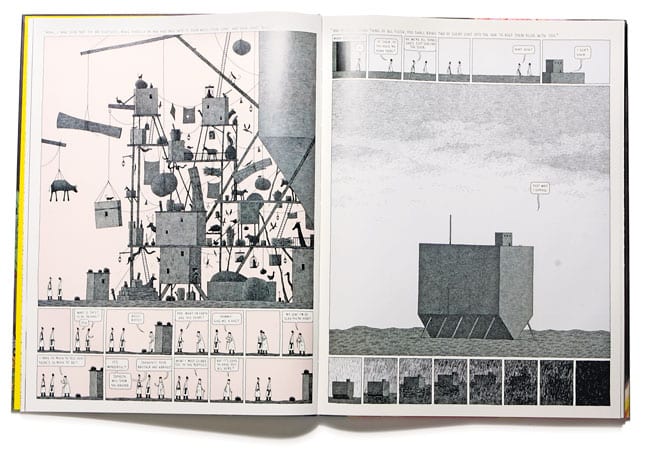

In Goliath, his first long book from Drawn & Quarterly, Gauld retells the story of the biblical character who was largely missing from the original version. Most of the story happens while nothing is happening. It’s Goliath and his sword-bearer — a small boy appointed to wait with him and carry around a pointless bit of armor — sitting on a rock, waiting. Somehow in reading it you forget you know how the tale ends and when it does it winds you. It’s one of my favorite things to come out in years.

The following interview was done by me in my pajamas in a room in East London, and a jet-lagged Gauld on trains, planes, phones and computers during his North American tour. He was very nice about letting me bother him when he was so busy.

HAYLEY CAMPBELL: You’ve drawn more astronauts, space stations and robots that any other cartoonist I can think of. Did you always want to be a cartoonist when you grew up, or are you mourning an unreachable jet pack?

HAYLEY CAMPBELL: You’ve drawn more astronauts, space stations and robots that any other cartoonist I can think of. Did you always want to be a cartoonist when you grew up, or are you mourning an unreachable jet pack?

TOM GAULD: Growing up I always (except for occasional ideas I'd be a soldier or doctor and, on one occasion, the Pope) wanted to do something creative which mainly involved drawing: an artist, an animator, a cartoonist, a model maker. Thinking back, I never wanted to be an astronaut, in fact I had very little interest in the reality of space, I was interested in science fiction. I was obsessed by the Star Wars films, toys and comics and I think these influenced the things I like to draw to this day. There is something which interests me about the gulf between our reality now and the optimistic science fiction (and speculative non-fiction) which I saw as a child: space travel, jet packs, flying cars etc. Living on the moon, for example, seems a quaintly old-fashioned idea to me now.

CAMPBELL: Arf! Seriously? The Pope? Why?

GAULD: I can't remember why, I was quite young. He'd been on TV and I imagine I liked his popemobile. We weren't Catholics, hardly religious at all really.

CAMPBELL: In some respects I think that would make it easier to adapt a biblical story. I was dragged through Catholic school for the whole stretch and now — even though some of the stories are the most amazing and gruesome and strange stories there are — I just can’t face them. They immediately make me feel like I’m wearing an uncomfortably scratchy uniform and shifting awkwardly in a pew while the priest drones on and on.

GAULD: Yes, I think that's true. I don't have a religious faith, but I'm interested in the Bible because the stories are such well-known, common parts of our culture. A few years ago I did a version of the story of Noah (for Kramers Ergot 7) and I liked that I could rely on the reader's knowledge of the story, and play with their expectations. That story was one of the things which led me to do Goliath. I didn't want my book to be anti-religious, or even to paint David as a fraud or a villain, but the God (or maybe just strong religious faith) which makes David so powerful is definitely not there for Goliath.

CAMPBELL: I remember the giant being just a fleeting mention in the actual story — hardly top billing. Is that why you picked him?

GAULD: In the Bible version he's hardly a character at all. He's more of a list of measurements: How tall he is, how long his spear is, how much his armor weighs. If the story had been more even-handed, or given more detail and character to Goliath, I doubt I'd have been interested in adapting it. I feel that the story was so one-sided that it almost begged for another view. One thing I realized while making the book is that we usually think of the story as "Boy vs Giant," but it's actually "Boy and Supremely Powerful Creator of the Entire Universe vs Giant," and seen like that, you can't help having a bit of sympathy for Goliath.

CAMPBELL: In this (and a lot of your work) I get the sense that you’re very aware of gaps. I mean, your whole version the Goliath myth takes place in the gap between two verses of someone else’s version. And then the most important bits of your story are happening in the gap, in the unspoken bit. It all seems to happen in the waiting, and the dialogue is so everyday and normal that the big heartbreaking bits are busily breaking your heart in the background.

GAULD: I find that I really enjoy it when an artist leaves me to make a bit of a leap from one thing to the next, rather than leading me along every step of the way. I try to do this in my stories, to leave gaps which the reader can fill in, but not so big that they feel confused. To put it another way, Billy Wilder said that in screenwriting if you "Let the audience add up two plus two. They’ll love you forever."

I like deadpan comedy, flat dialogue, things happening offstage and inexpressive characters, there's probably some deep psychological reason for this, but another reason goes back to not wanting to lead the reader by the nose by signposting "THIS IS FUNNY!" or "HOW TERRIBLY SAD!" and allowing some of it to happen in the reader's mind.

CAMPBELL: You zoom in and focus on one tiny aspect of some great epic, like Roz Chast including the dog’s flea in the family tree. In a lot of articles about you the writer is always quick to liken you to Edward Gorey, and from the cross-hatching you’re evidently a great fan, but I’ve always identified an element of Chast in there.

GAULD: I used to see Chast's cartoons in The New Yorker occasionally but it wasn't until I bought her big retrospective book Theories of Everything a few years ago that I realized how great she is. So she wasn't a major early influence but more recently she's inspired me (particularly on the cartoons I do for The Guardian). Also we both like to do diagrams and lists and there's some similarity in tone.

CAMPBELL: My favorite thing by you that I’ve seen recently is The Triumph of Death strip that you did for Art Review magazine (above), in which you do just that — you take two (essentially binmen) bit-players and put them center-stage. A painting like Bruegel’s is so cartoony and detailed that every time you look at it you see a new guy, a new tiny tragedy. I interviewed Anders Nilsen when he was in London, and he said you took him to the John Soane Museum to see the Hogarths. As an artist, what is it you like so much about that kind of stuff?

CAMPBELL: My favorite thing by you that I’ve seen recently is The Triumph of Death strip that you did for Art Review magazine (above), in which you do just that — you take two (essentially binmen) bit-players and put them center-stage. A painting like Bruegel’s is so cartoony and detailed that every time you look at it you see a new guy, a new tiny tragedy. I interviewed Anders Nilsen when he was in London, and he said you took him to the John Soane Museum to see the Hogarths. As an artist, what is it you like so much about that kind of stuff?

GAULD: Thanks, I'm glad you liked that strip. Earlier this year I went to Avantcomic, a comics conference in Madrid and I also went to see The Triumph of Death at the Prado, it's in the same room as The Garden of Earthly Delights which I love too. I looked at it for ages, there's so much going on, such a weird atmosphere and so many stories being hinted at and I decided then that I'd write a story about the two skeletons on the horse and cart. I went to see the Goya black paintings there too, and they are like the really bleak visions of a depressed man, whereas The Triumph of Death is dark, but it's also funny and Breugel is clearly having such fun painting all these skeletons and crazy atrocities. It's a bit like Where's Wally (Waldo) with skeletons.

CAMPBELL: Years ago I became kind of obsessed with Hans Holbein’s Dance of Death stuff. It’s just so nuts and cartoony with the skeletons mocking whoever they’re dragging down by prancing around in the guy’s hat or cape or whatever. Then there’s someone else trying to bribe the skeleton while he nonchalantly looks the other way, or the skeleton tipping a gallon of booze into the collapsed drunk’s mouth. And that’s just the tiny illuminated alphabet. The actual Dance of Death set is even madder. Death taking an ancient old man to see a physician and then handing the guy a urine sample (presumably) as if it’s some kind of challenge.

As for Bosch, I’ve never seen The Garden of Earthly Delights in real life, but they’ve got one of three known sixteenth-century copies of the central panel at the Wellcome Collection. I was staring at it just a week ago. After much thought I decided the best bit is the man sticking a bunch of flowers in the lady’s bottom.

GAULD: I didn't realize that the Wellcome had a copy of earthly delights, I'll have to go and see it.

I love Hogarth's series such as The Rake's Progress, partly for the lovely drawing and engraving (I prefer his prints to his paintings) and also for the stories. It takes a bit of work to read the story in The Rake but I think that's the fun: noticing the details, comparing each plate to the next, filling in the gaps.

CAMPBELL: I prefer the prints too. Everyone seems craggier and they pull better faces. Anders said he liked how nuts the Hogarths were, with the crazy unexpected details (“Like pigs tied to people’s heads and stuff,” he said). London’s obviously full of great old prints and drawings — are there any others you like to show visiting cartoonists?

GAULD: I also took Anders to the prints and drawings collection at the British Museum, they have some really great shows there and even though we only had about 15 minuted before they closed we dashed round a German romantic prints show which was full of super-crosshatchy forests and things. I like the British museum generally, I started going quite often as it was opposite Gosh, so I could buy some comics, look at some old etchings (or pots or whatever) then sit in a cafe and doodle.

CAMPBELL: Now, getting back to Gorey for a bit. Sometimes your strips (particularly your older ones) are not really about much but they have an overwhelming sense of atmosphere, which is something Gorey always excelled in too. Is there anyone (in comics or otherwise) who you regard as a master of atmosphere?

GAULD: I do love the atmosphere in Gorey's work, I suppose atmosphere is a big part of his work. I must admit that much as I love Gorey and think he is an amazing genius, I do sometimes wish there was a bit more depth and heart to his work. I think that Jason's comics have a wonderfully idiosyncratic atmosphere to them. I think his stories get better all the time, and the colours that Hubert does for him are so perfect, I think they really add a lot to the stories. Mike Mignola is great at atmosphere too, he's made a really interesting world in his comics, seemingly by just sticking together all the cool things he likes to draw. Dave Stewart’s colours in that are really good too. I guess with all three of these artists I feel that all their work comes from a distinct, invented place, and I really like it when artists make up their own worlds.

CAMPBELL: I remember reading, years ago, that you were a fan of Ben Katchor and his particularly New York atmosphere in Julius Knipl, Real-Estate Photographer. Michael Chabon wrote a piece — I read it in a collection of his essays but I think it was originally the introduction to Julius Knipl — in which he said Katchor is “more – far more – than a simple archaeologist of out-moded technologies and abandoned pastimes. In fact he often plays a kind of involuted Borgesian game with the entire notion of nostalgia itself, proving that one can feel nostalgia not only for times before one’s own but, surprisingly, for things that never existed.”

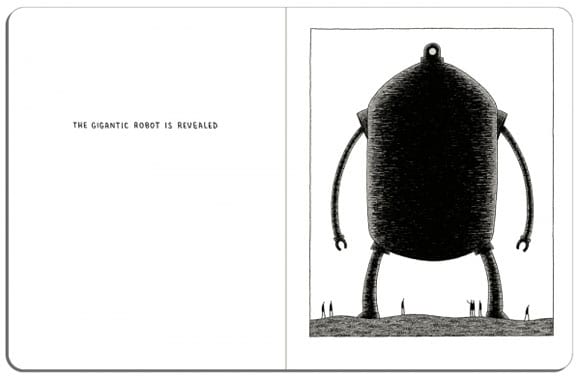

I feel the same way about your moon stuff, or The Gigantic Robot. There’s nothing lonelier than a space station but you go one further and do abandoned space stations or moon dwellings. A piece of yours that always stuck in my memory was actually a mistake: the Lost Robot, where you had meant to scan just the robot but ended up with the entire scanner bed thus placing the little guy on the most bleak lunar landscape. There’s a nostalgia there — or at least a sense of the optimism of the past that you mentioned earlier — for a thing that never existed.

GAULD: That's interesting, I've been a fan of Katchor's work for a long time now, I wrote my MA dissertation (admittedly a short art school dissertation) about his work. I hadn't seen that connection before but now you mention it I can see it. I think you can feel, upon seeing my robots or technology (or maybe even everything I draw) that things will probably go wrong at some point.

I don't think I'm saying that life was better in the past, or now, or even in the future. My characters are often just clumsily trying to make the best of things, wherever they are.

CAMPBELL: I was down the pub with Andy Riley the other night and we got onto the subject of your Hunter & Painter. Andy was adamant that it would make a brilliant Aardman short film and I wholeheartedly agree. I know Matt Abbiss has animated your work in the past [a subtitled version exists on YouTube here]. Would you do it again?

GAULD: I've worked on animations for commercial jobs and it was fun to see what Matt did with Invasion, but I'd definitely like to work on an original animation one day. When I was at college in Edinburgh, I did some animation in my first year but when I specialized I chose illustration as animation seemed too meticulous. Comics are a lot of work but animation (especially in those less digital times) was too much. I'm wary of, and also excited by, the idea of collaboration. I like that I have almost complete control of my comics but I couldn't make a film on my own, so it would have to be with the right people.

CAMPBELL: The more I learn about the process of filmmaking the more astounded I am that any good ones ever get made.

Andy would also like to know if you ever break loose and draw something huge. He is a man who has just realized that having bought his own house he can now paint cartoons on the walls if he wants to (and has done so).

GAULD: I never draw things big. Even if something needs to be big, I'd still draw it small and scale it up. I like to draw small (my drawings are not much bigger than the finished, printed comics) as it reigns in perfectionism, and I get a bit of natural wobble and error into the drawings. One problem with digital is that you can zoom in and in forever: but with a pen, the width of the line gives a natural end.

CAMPBELL: So what are you working on now? Did you like the process of doing a longer work and would you do it again?

GAULD: Making a longer book was really hard, but in the end very rewarding. Working on Goliath there were a lot of wrong turns and failed experiments but I learned from it. I'm just starting to work on a new book which I think will be longer than Goliath and am also working on a collection of the short, weekly strips I do for the Guardian.

CAMPBELL: Can you tell us what it is yet or will we have to wait and see?

GAULD: I can't really. I have a couple of ideas at at such early stages I may scrap them and do something else. But whatever I do I'd like it to be a bit longer than Goliath was. My next published book will be the Guardian strips collection.

CAMPBELL: Will you ever collect your Time Out strip, Move To the City? I wasn’t in England when it was appearing in the magazine and I never saw it.

GAULD: I think it'll reprint one day, but not right away. I have mixed feelings about it. It was a great job to get: a paid, weekly comic strip when I was only few months out of college, but the weekly deadline, the fact that I hadn't drawn many comics before, and was really busy with other things mean that it's quite uneven. I enjoyed it, experimented with it and learned a lot from it, but I'll wait till I have a few other things in print before I revisit it. It did come out in French from the Swiss publisher Bulb (and actually appeared as a daily strip in a Geneva newspaper) but that was because Nicolas Robel, the publisher, was very enthusiastic and talked me into it.