Joshua Cotter is hoping there’s at least one seat in the Riffe Center in Columbus, Ohio that’s completely engulfed in shadow, where he can sit to watch the stage adaptation of his comic book Skyscrapers of the Midwest without anyone there knowing that he’s him.

“There was this one time when I was a kid and I went to the circus and the clowns were doing their thing and they started looking for a ‘volunteer,’” Cotter explains. “And out of all the people in that building the clown leader actually managed to spot me hiding behind the bleachers (I was hiding from the clowns) and brought me out and humiliated me by repeatedly pitching me a cartoon-sized baseball that I would never be able to hit because the cunning fellow had tied it to a bit of elastic string.”

“So basically, I’m hoping nothing like that happens,” he says, although morbid curiosity compels him to see the performance.

Cotter probably doesn’t need to worry. There are no clowns in the original comics, and Matt Slaybaugh who researched, adapted, wrote and directed the play, stayed quite faithful to the book that inspired him to undertake the year-long project. Certainly he was faithful enough to the source material not to insert cruel clowns bent on humiliating Joshua Cotter.

Slaybaugh is the artistic director for Columbus-based Available Light Theatre, a company that specializes in creating plays based on unusual source material. While the medium he works in is theater, he’s long been a great fan of the comics medium. He grew up reading Marvel comics and “everything with capes” until about the early '90s, then went into a phase of flirting with Vertigo and Wildstorm comics until sometime in the mid-aughts, when he discovered the work of cartoonists Seth, Joe Matt and Chester Brown. Guided by his friend Max Ink, the Columbus-based cartoonist responsible for slice-of-life comic Blink, Slaybaugh started voraciously reading the likes of Kevin Huizenga, Chris Ware, Paul Hornschemeier and Dash Shaw.

“People called them ‘slice of life’ comics, and I was so grateful that people were writing about the mysteries of everyday existence in my favorite medium,” Slaybaugh says of the discovery. But despite all the great comics by great cartoonists creating stories that dealt with issues of great interest to him, there was something special about Skyscrapers for Slaybaugh.

“It’s my favorite comic ever,” he says. “That’s a bold statement, but it’s true. I think Josh is a genius in the way he uses the medium and his art is simply beautiful. It was shortly after I'd received the collection that I was thinking about the stories, and the way they fall into that gap between reality and imagination. The plays I like most do the same thing.”

There was also the fact that Cotter’s experiences seemed to mirror Slaybaugh’s own. While Cotter was raised on a farm near a tiny town in Missouri, where the comic is set, Slaybaugh was born in Cleveland and raised in Columbus, Ohio, an his family now lives in a suburb of Columbus. Not exactly the most rural part of the state, but in many ways the Midwest is still the Midwest.

“It's almost disturbing how much of the book reflects very specific instances in my life, and many of our collaborators have said the same thing,” Slaybaugh says. “It really demonstrates how universal these experiences are. And it's not just the events, but the long-term emotional effects of those events. People of certain type exit childhood with a lot of confusion, guilt, and loneliness. Aside from robots and dinosaurs, that's what Josh really wrote about, in a ruthlessly honest way, and that's why the book is so powerful.”

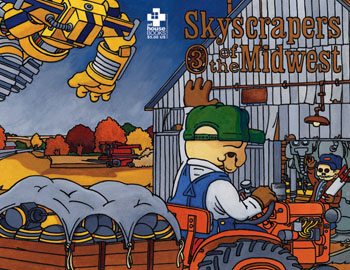

Using anthroporphic cats as human stand-ins, Cotter’s series reflected on the growing pains of a kid as he came to grips with life and experienced the growing pains of his older brother vicariously. The line between imagination and reality regularly blurring, as a giant robot serves as a sort of Midwestern god figure, space ships and a dinosaur make appearances.

Skyscrapers began as a minicomic, winning the 2004 Isotope Award for Excellence, and then became a serially published comic book from small, boutique publisher AdHouse, with four issues released between 2004 and 2007. AdHouse ultimately collected and released in 2008 as a graphic novel, and AdHouse publisher Chris Pitzer considers it one of his defining books.

The covers of the comics, populated by skeleton farmers, robots and rabbits in high-tech battle suits, and other comic book trappings like fake ads for fake cigarettes and a letter column featuring a belligerent cowboy, make it seem like a far stranger comic than even Cotter’s drifting from perceived reality to real reality.

The covers of the comics, populated by skeleton farmers, robots and rabbits in high-tech battle suits, and other comic book trappings like fake ads for fake cigarettes and a letter column featuring a belligerent cowboy, make it seem like a far stranger comic than even Cotter’s drifting from perceived reality to real reality.

Slaybaugh knew there were easier comics to try adapting to the stage, but he liked the challenge Cotter’s fantasy sequences provided, so he tracked down Cotter online and then sent him an email to gauge his interest.

Cotter says he was mostly intrigued. “I honestly don’t know much about ‘the stage,’ as we call it in ‘the biz,’ but once I did some research on Matt’s Available Light company and came out convinced of their ability, I figured it might be interesting to see what they come up with.”

Well, that and the flattery. “Flattery will get one everywhere with me.”

In addition to reading the book about 20 times in a row, taking notes, and trying to figure out how to stage the scenes in his head and how the scenes all related to one another, Slaybaugh functioned a little like a reporter.

In December of 2010, Cotter’s Chicago apartment caught fire and the artist moved back to Missouri with his parents while a new place was being built—“To strengthen what one might consider to be my street cred, I'm living with my parents (In the basement!),” Cotter said—and so Slaybaugh ended up visiting the artist and staying in his childhood home.

“In his childhood bed, as a matter of fact,” Slaybaugh said. “I met his family, who are central to the book. He took me to all the places in the stories. It was a wonderful few days. I came home with a much, much deeper understanding of what the book is about. I don't like to use the word, but it is appropriate to say that it was fairly surreal. Rex, a big character in the book, was on the dresser in the room I slept in.”

He also spent about six hours in front of a fireplace, just talking to Cotter and recording the results. This lead to dramatic change between the comic and the stage play—the adult Cotter is actually a character in the play, appearing between scenes taken from the book to give an adult perspective, culled from those conversations, and adding a second coming of age story to the narrative.

Cotter’s version of Slaybaugh’s visit is a little different: “We fed him head cheese nearly every meal and made him sleep in the old barn with an abnormally feisty and large family of raccoons, but only because he was insistent on ‘keeping it real’. We did a lot of talking/interviewing while trudging around on the back 80 through waist deep mounds of snow.”

Aside from making Slaybaugh’s research sound a lot more dramatic, Cotter’s been as hands off with the adaptation as possible. “If I maintain a hands-on approach, things usually turn out a lot worse than you or anybody could possibly ever imagine,” Cotter explains.

Slaybaugh’s fellow company members were quite hands-on however; Dave Wallingford, Brant Jones, Tony Auseon and Michelle Whited were all heavily involved in brainstorming how to “stage the imagination,” and then in pulling it off.

The result involved what Slaybaugh calls a poor man’s blue screen effect, with actors in front of a rear-projection screen on-stage and Jones, the video designer, visible on-stage filming the scene, which is then being projected onto a larger screen above the stage.

The hoped-for effect is that of the scene being created right before the audience, which parallels the thing Slaybaugh likes most about slice-of-life comics, and Cotter’s in particular—the awareness that human hands drew them and, seemingly, drew them just for the individual reader.

Not that Cotter made Skyscrapers specifically for Slaybaugh, of course. Although that’s not actually too far off from the audience he had in mind.

“I write and draw what I would like see more of out there in the comic/art world,” Cotter said of his imagined audience when making comics. His follow-up to Skyscapers, 2009’s Driven By Lemons, a bizarre, barely-narrative, stream-of-conscious “sketchbook replica” is a pretty good demonstration of that.

“And I assume/hope that out of 6.75 billion people, there might at least be a couple who share some common interests with me and connect with whatever it is I happen to be writing or drawing,” Cotter says.

Obviously, more than a couple connected with Skyscrapers of the Midwest, and, if Slaybaugh and Available Light’s adaptation finds a wider audience than curious comics fans, it will be connecting with many more over the course of its two-week run.

Both creators are already looking forward to more work in one another’s medium. Slaybaugh says he’s looking forward to picking Available Light’s next comics adaptation, and is interested in exploring how Huizenga mixes fiction and non-fiction, or how Jeffrey Brown’s rough aesthetic could be stage.

And as for Cotter? “As a challenge for Matt, or any playwright, for that matter,” Cotter says, “Lets see what you can do with Driven By Lemons. As a musical.”

All performances:

Riffe Center Studio Two Theatre

77 South High St.

Columbus, OH

See a map and get directions.

Performance Schedule:

Thursday, April 21 @ 8pm + TALKBACK

Friday, April 22 + TALKBACK

Saturday, April 23 @ 8pm