Joe McCulloch is back again, with a review of Josh Simmons and Patrick Keck's unofficial Batman comic, Twilight of the Bat.

This is the second unauthorized Batman comic to be written by Josh Simmons, that unsparing specialist in physical, emotional and moral breakdown. The first one was a self-published minicomic printed in 2007 under the simple title of Batman and subsequently posted online; it depicted the caped crusader at his most ideologically severe, lecturing a disgusted Catwoman on how he's devised a magnificent means of permanently disfiguring criminals. Batman cannot ever kill, you see, so it's crucial that the superstitious and cowardly lot that is the criminal element be marked - to live forever with the shame of their transgressions, and to be shunned, then, by all the good people of society. On its own, this is not an original idea. Lee Falk's transitional superhero character and Batman predecessor the Phantom left the mark of a skull on the jaws of those villains he struck, while the yet-earlier pulp character the Spider stamped his brand upon the foes he felled, but Simmons' Batman is depicted with unusual intimacy: knees pressing against his chin as he curls up to dream of packed prisons and children getting blasted with fire-hoses, swooning ecstatically, high above a tottering riot of Gotham rooftops.

Meanwhile, elsewhere:

—Interviews & Profiles. Chris Ware continues to promote his backbreaking new career retrospective, Monograph, which is more or less essential reading for his enthusiasts, and may be the only person alive to appear in the same week on both Charlie Rose and Inkstuds.

At Vulture, Abraham Riesman interviews Walking Dead co-creator Robert Kirkman about his new TV documentary series, Robert Kirkman’s Secret History of Comics, focusing on the "really, really ugly history of the comic-book industry," specifically in regard to creators' rights. (Strangely, Tony Moore's name never comes up.)

Was it hard to get DC and Marvel to play ball, given that a lot of the episodes are pretty critical of them?

A little bit. DC seemed to cooperate a little more than Marvel did. We got access to [DC co-publisher] Jim Lee for the Image episode, which we’re very grateful for. They were very involved in the Milestone episode because they’re doing a Milestone relaunch. But, y’know, I think that a lot of the worst things that Marvel and DC have done in their history, hopefully, are behind them. I think that it’s different people at the helm at this point, and I think they recognize that. So, it wasn’t too terribly difficult. And it’s not like the people that work at DC don’t think that [Superman co-creators Jerry] Siegel and [Joe] Shuster were given the short end of the stick.

At Hyperallergic, Angelica Frey profiles the mysterious GG.

GG chose to publish pseudonymously, as she does not want her work and her art to be overshadowed by her personality or backstory. In fact, when she started seriously writing comics, she initially only wanted to publish online and anonymously. “I agree with Elena Ferrante, who’s stayed totally anonymous, that books don’t need their authors once they’re written — if the work has something to say, it will find the right people to hear and understand it without the author having to speak for it,” she elaborated to me. And indeed, despite GG’s austere and allegorical modes of storytelling, the theme of alienation in I’m Not Here resonates loud and clear.

And CBS Sunday Morning interviewed George Booth:

—Reviews & Commentary. Simon Willis writes about a London exhibition of Tove Jansson for the NYRB.

The popularity of the Moomins spawned an empire of television shows, films, and theme parks, as well as all manner of merchandise from plastic toys to crockery.

But over time, Jansson came to feel exhausted by the Moomins and that their success had obscured her other ambitions as an artist. In 1978, she satirized her situation in a short story titled “The Cartoonist” about a man called Stein contracted to produce a daily strip, Blubby, which has generated a Moomin-like universe of commercial paraphernalia—“Blubby curtains, Blubby jelly, Blubby clocks and Blubby socks, Blubby shirts and Blubby shorts.” “Tell me something,” another cartoonist asks Stein. “Are you one of those people who are prevented from doing Great Art because they draw comic strips?” Stein denies it, but that was precisely Jansson’s fear.

At LARB, John W.W. Zeisser writes about Peter Bagge's Fire!!

Fire!! takes its name from the short-lived literary journal [Zora Neale] Hurston co-founded and edited with other Harlem Renaissance luminaries, including her roommate Richard Bruce Nugent, Langston Hughes, Wallace Thurman, Countee Cullen, Gwendolyn Bennett, and several others.

Fire!!, which was meant as a shot across the bow of the respectable, middle-class black literary production favored by the likes of Alain Locke and W. E. B. Du Bois’s “talented tenth,” reflects Hurston’s idiosyncratic ideas and deep commitment to African-American cultural production. The journal set out to give voice to the “low” art of Harlem and address many of the taboo issues within the community, including homosexuality, interracial love, and racism. However, Hurston et al. only managed to produce one issue before their headquarters burned to the ground. As Bagge has Hurston say to Bruce Nugent upon hearing the news, “Pretty prophetic, huh?”

Yussef Cole uses the recent video game Cuphead to explore racialist caricature in early American animation and its echoes in contemporary art and culture.

After World War II, when the NAACP and other organizations ran campaigns criticizing explicitly racist caricatures in animation, the industry responded by simply ceasing to create black characters of any kind. In Christopher P. Lehman’s The Colored Cartoon he writes: “No theatrical cartoon studio created an alternative black image to the servile, crude, hyperactive clowns of the preceding half-century. The cartoon directors of the 1950s, many with animation careers dating back to the 1920s, had no experience in developing such a figure.” Studio MDHR, in interviews, is quick to point out that they avoided stereotypes in Cuphead; that they focused on “the technical, artistic merit, while leaving all the garbage behind.” The truth may be dirty, and often uncomfortable. But it’s preferable to offering up a bleached white past, while pretending nothing was lost in the process.

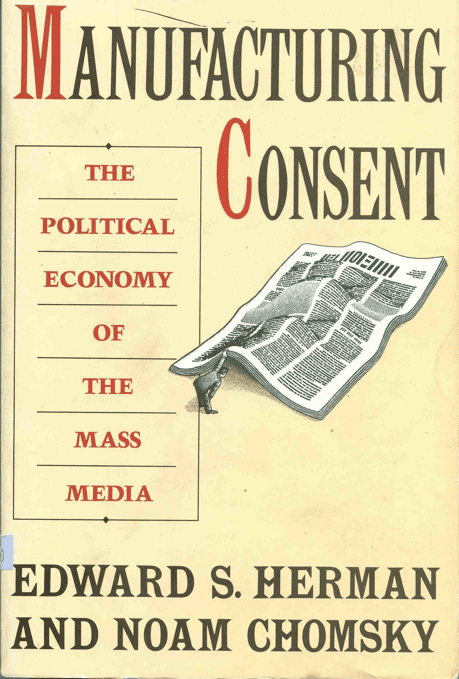

RIP Edward Herman.