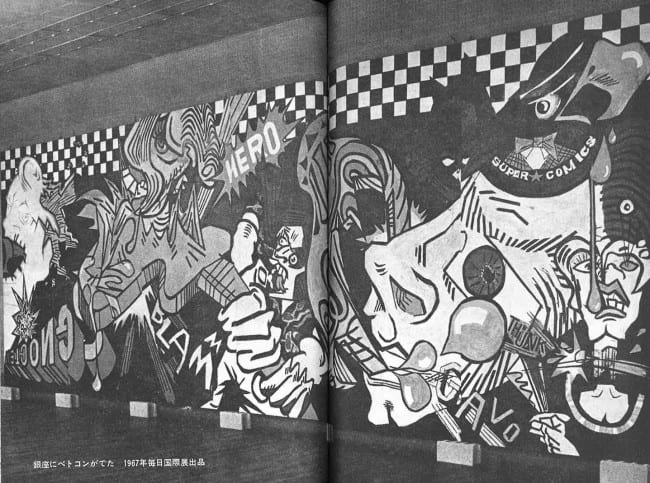

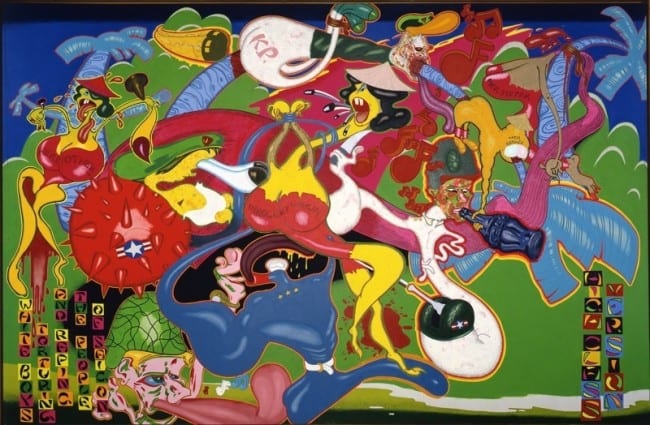

Around the same time as “VietCongs,” Shinohara created the mural-sized painting The VietCongs Do the Ginza (Ginza ni betokon ga deta) for the 1967 Tokyo Biennale. Though the work was subsequently destroyed, a black and white photograph in The Avant-Garde Road shows it installed at the Biennale propped on cinder blocks.

Its composition marks a real departure for the artist. Previously, Shinohara’s figurative work was characterized by a high degree of flatness. His Edo Pop paintings and prints of the years just preceding were either primitivizing in their rendering of form and evacuation of space (The Twenty-Eight Notorious Murderers or Okichi Story, both 1965) or they obediently followed recent trends in abstraction and designs with a decorative emphasis on surface pattern (the neon yakusha-e paintings and silkscreens of 1966-68). This earlier work can be flamboyant, but energies tend to move laterally across the picture plane, rather than outward at the viewer, as is the case with the heaving masses, bombastic pop-outs, and bulging 3D fonts of The VietCongs Do the Ginza.

What finally turned him on to this bigger stage for “action” within figuration? Most likely American comics, and it seems specifically DC Comics. Conventional sound effects like “BLAM” could have come from anywhere. But the racing check that runs along the top of The VietCongs Do the Ginza is the same that decorated the covers of DC Comics in these years (1966-67). “Don’t hesitate – choose . . . the mags with the go-go checks,” urged one in-house ad. “For the most in thrills, go-go-go,” went another promoting Superman titles. Considering the peppy verbiage bouncing across both of the VietCong works, as well as their musical setting, did the term “Go-Go” behind the checkered stripe register for Shinohara? A similar racing check, by the way, appears decorating the stage of Nikkatsu’s Youth a Go-Go, so this wasn’t an esoteric motif.

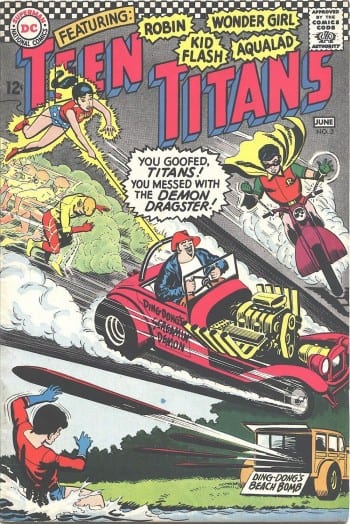

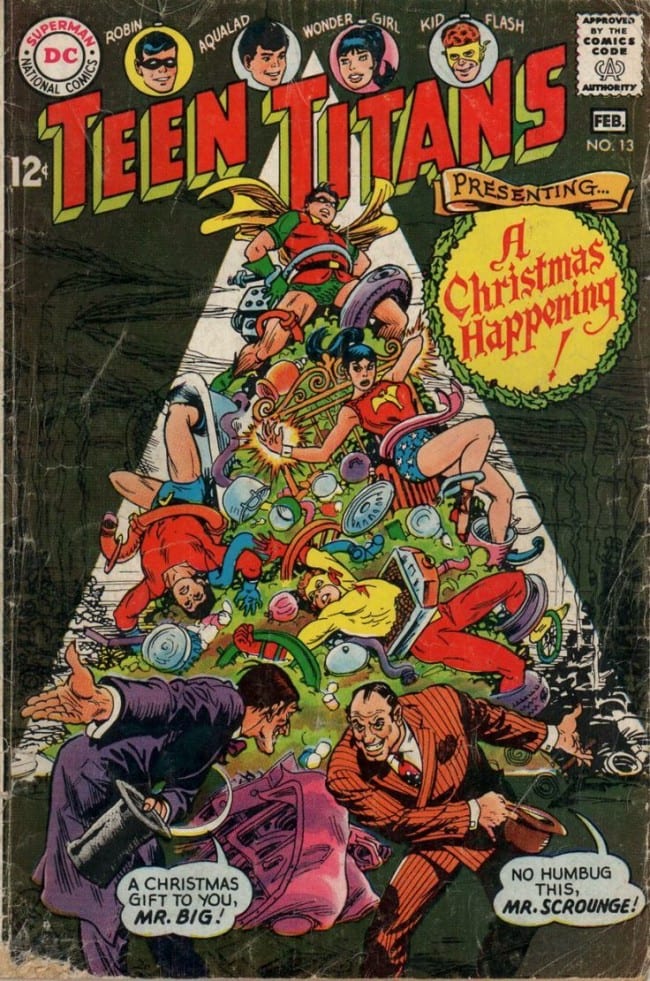

Given Shinohara’s own identification (despite his older age) as a leader of Japan’s youth brigade circa 1960, it is appropriate that the American comic book he appears to have been most attracted to was Teen Titans. The original Titans, which debuted in DC’s The Brave and the Bold in 1964, consisted of Robin the Boy Wonder, Kid Flash, and Aqua-lad, the sidekicks of Batman, Flash, and Aqua-man respectively. Joining in the third installment was Wonder Girl. The group was essentially a junior iteration of DC’s Justice League of America, the popular superhero team that included the Teen Titans’ mentors along with other DC stalwarts like Green Lantern and Superman. Not only young in age, the Teen Titans oftentimes aided American teenagers in mortal need or simply misunderstood by mom and dad. “Writer Bob Haney found just the right line between rebellion and conservatism,” notes Paul Levitz in his monumental survey of DC. The Titans “sometimes fought square adults, but just as often saluted President Johnson or took on bikers, hippies, and other rabble-rousers.” Their heroics take them into juvenile delinquency-plagued Averagetown, America, into the heart of the Inca highlands to help the Peace Corps against “reactionary” forces that oppose development, and even once to the terrorist-threatened Tokyo Olympics – but why in an issue dated 1966, two years after the games? Probably because that was the year The Beatles played Japan. References to the British Invasion are frequent in the comic book. The Titans are even nicknamed “The Fabulous Foursome.”

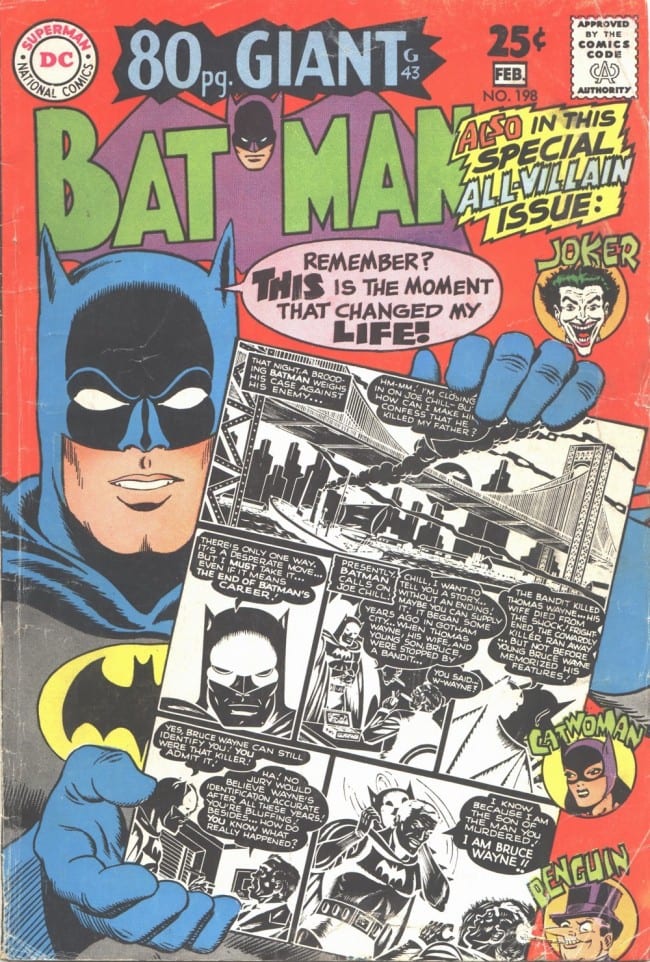

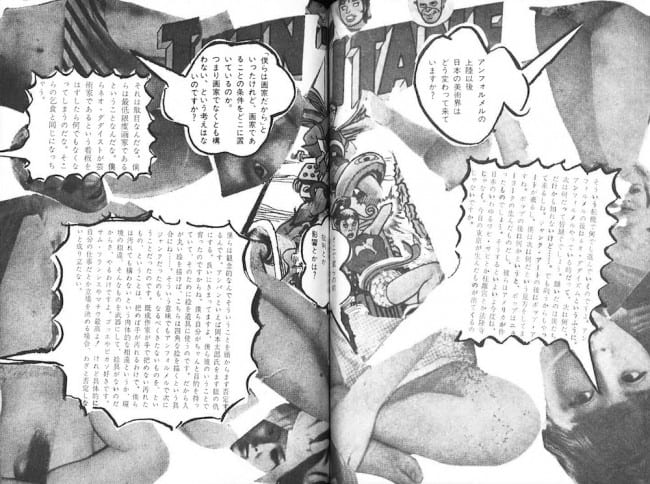

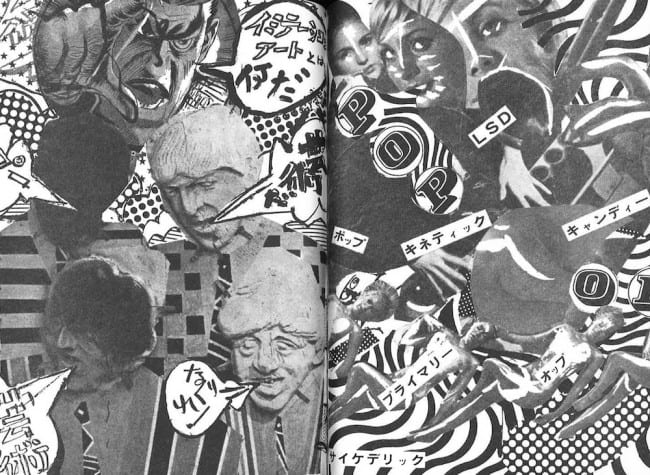

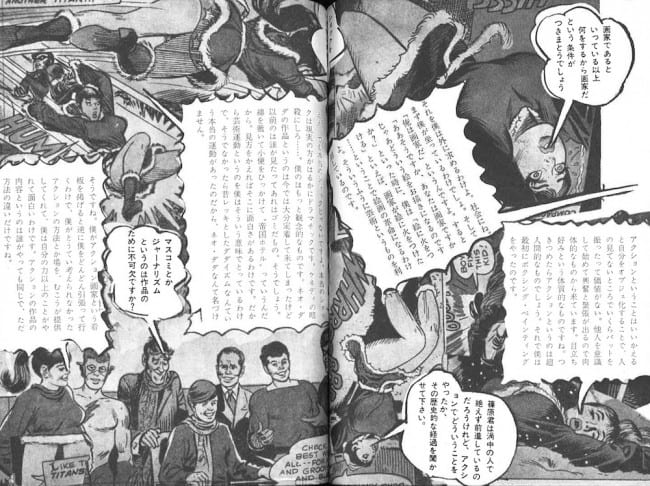

For the drawings of The Avant-Garde Road (1968), Shinohara clipped out verbiage, bodies, and heads from various comic books. There is, for example, one Batman head and one Batman hand, both from the cover of Batman no. 198 (February 1968). Gotham’s caped crusader is made to respond, as if he is Shinohara, to questions about his beginnings as an artist and the impact of Art Informel. “If that were me, I thought I could do something tougher, a performance that was over-the-top and that really moved around,” says Batman’s hand. “That was what action painting made possible and that’s what turned me on.” The female fighter from "VietCongs" appears inverted on the facing page.

Yet Shinohara does not appear to have been as interested in camp icon Batman as, say, his friend Tana’ami was. Most of the collaged comics in the book come instead from a single issue of Teen Titans, no. 13 (January-February 1968).

The story is a retelling of A Christmas Carol, with “Mr. Scrounge” involved in a strange racket of importing junk cars, motorcycles, and appliances from overseas and selling them to goons who, using a special gun, magically convert the junk into shiny new goods and sell it at high market price without paying import duties. For this issue, artist Nick Cardy draws in his best imitation of Will Eisner, for whom he had worked in the early 1940s. Perhaps the overt stylization is in homage to Eisner’s Christmas stories for the Spirit?

That doesn’t really matter for Shinohara. It doesn’t seem that he had any particular interest in the caricatural exaggerations of Cardy’s drawing style. Shinohara has cut and glued one close-up of Mr. Scrounge’s face, angry and pointing. But then he has gone over part of the image with ink, flattening it out, making it more “painterly” than cartoony.

When I first saw this face, I thought it had come from Saitō Takao’s manga. That Saitō emulated Eisner and Jack Davis is tangential to the present discussion. So is the fact that, right around this time, Shinohara began reading Shōnen Magazine, using pieces of Saitō’s Muyōnosuke and Kawasaki Noboru and Kajiwara Ikki’s The Star of the Giants in sci-fi collages made soon after The Avant-Garde Road. That’s another article, another time.

Returning to The Avant-Garde Road, most of the images he has taken from the Titans’ A Christmas Carol feature Wonder Girl being yanked through the air and slammed to the ground by a magnetic crane and then by a magnetized junk-pile Christmas tree. This tree is also depicted on the comic book’s cover, which Shinohara has also used.

“Tana’ami was a big Wonder Woman fan,” Shinohara said recently. “So was I, probably just because she was a woman.” DC did just as much to sexualize her junior edition, Wonder Girl, who is often referred to in Teen Titans as “Wonder Doll” and “Wonder Chick” and the like, and who cannot go two issues without enticingly swaying her hips to music. Shinohara has caught her with her Santa’s Helper outfit flapping high above her bloomers. Through the added speech balloons, she is made to discourse with Shinohara on the relationship between “action” and what it means to be a painter. Despite distracting the heroine thus with art talk, the page manages to end, as the original comic does, happily with the Titans and Mr. Scrounge smiling around “Tiny Tom.” His original wish to all “for a swinging and groovy new year” is half obscured. Instead he asks, “Are media and journalists a necessary part of your artwork?,” referring to Shinohara’s camera-prepared action paintings of seven-eight years earlier.

What was it about Teen Titans that appealed to Shinohara? Many DC comics under the Code were heavy-handed in their moralizing, the Teen Titans especially so, designed as the title was to provide idealized mirror images for its teen readership. Pop culture was actively exploited to this end, as it was to increasing sales. The Titans often slip into forty-year-old writer Bob Haney’s pained idea of whippersnapper street talk, saying things like “dig” and “groovy” and “see you later alligator,” “cool cat,” “natch,” and so on. The Dickens adaptation is introduced as a “holiday happening.” There is nothing to suggest that Shinohara regarded Teen Titans as condescending (though some of its American readers did, judging from irritated entries in the letters page). But clearly he recognized Teen Titans as the superhero genre’s homage to contemporary youth culture, mixing its drawings as he does in The Avant-Garde Road with photographs of cute white and Japanese girls, presumably clipped from fashion magazines, embellishing some with stripes of black and white, as if decorating them in body paint.

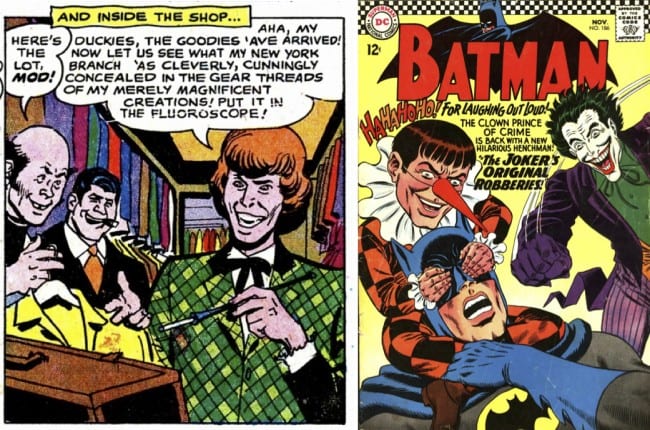

This youth culture vector comes out more clearly, and more compellingly, in the VietCong works from the previous year. For the Tokyo Biennale painting and the Bijutsu Journal comic, Teen Titans appears to have been a primary print media source. Further research would probably turn up issues of Batman or World’s Finest or Justice League of America that shaped these works. But one comic book that I know was there was Teen Titans, no. 7 (January-February 1967). That issue features the debut of “the grooviest, swingingest villain the fabulous Teen Titans have faced yet – the blitherin’ bloke they call the Mad Mod, the merchant of menace.” He is a fashion designer from the heart of Swinging London. He uses his clothes shop on Carnaby Street as a front to smuggle chemicals and jewels across international borders, hiding them deep in the weave of the spiffy outfits he designs for one of his clients, pop superstar Holley Hip.

As the story opens, Wonder Girl is cooing over a poster of Holley. The Titan boys naturally find him too much. So it’s with conflicting emotions that the group responds to a request from the U.S. Government to go on tour with Holley officially as part of “Uncle Sam’s Good Neighbor cultural exchange program.” Actually their task is to investigate Holley’s suspected role in trans-Atlantic smuggling – which turns out to be true, though unbeknownst to the pop star, who tours the world outfitted in the Mad Mod’s laced garments. The Titans head off on their mission with a salute to an oversize portrait of JFK captioned with the President’s immortal slogan – which rang shrill once conscription for the Vietnam War began – “Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.”

At the top right of The VietCongs Do the Ginza, there is a headless checkered suit. It is set within a broken roundel captioned “Super Comics,” adapted from the DC Comics logo that reads “Superman” and “National Comics” around its circumference. The suit itself is probably that worn by the Mad Mod, though at one point Holley Hip also dons this kind of checked item with large lapels. The bowtie is more Penguin-esque, as the Mad Mod usually wears a ribbon bowtie and Holley Hip a Windsor knot. Whatever the case, it is indicative of Cardy and Haney’s breezy handling of contemporary youth culture that the Mad Mod dresses (maybe I am revealing my own ignorance here) not like a Mod so much as a Teddy Boy, though I realize the styles were not always distinct in practice or in mass media coverage of London. Perhaps the history of fashion in DC Comics itself has contributed to the slippage. For the Mad Mod’s outfit (like his broad devilish grin) resembles no-one’s so much as the Joker’s, whose zoot suits and ribbon ties came from the same Chicago gangsters and American jazzmen and rockers whose look the Teddy’s partially emulated. The Joker of course was Batman’s nemesis, and the Titans are led by Robin. And though it’s hard to make out in the photograph, one can distinctly see Batman’s pointed ears and the crown of his head silhouetted against the “go-go” stripe next to the Mad Mod roundel.

Given Shinohara’s lack of English-reading ability, perhaps this was unintentional, or rooted in nothing more than a pedestrian association of American superheroes with American righteousness. It is, regardless, amusing that Shinohara would take these Peace Corps-promoting heroes and reinterpret them as a boy-girl-boy killing squad called the VietCong. Key is their contrasting relationship to youth pop culture. While the VietCongs set out to simply annihilate Electric Boom-Group Sounds headquarters, the Titans keep on good terms with starry-eyed fans and hippies as long as they remain decent junior citizens. Certainly the Titans combatted bad influences in youth pop culture, but these were usually figured as aberrations. Youth culture in itself was not only tolerated, it was embraced. As I mentioned before, Wonder Girl likes to shake her thang before or after missions, joined sometimes by the superboys. Pop music can even be the answer to problems. In one episode, “The Astounding Separated Man” (The Brave and the Bold, no. 60, June-July 1965), the titular purple monster is repelled by adolescents playing The Beatles’ “I Want to Hold Your Hand” loudly in unison on their transistor radios.

Likely this visualization of pop music mania was one aspect that drew Shinohara, the former “rockabilly painter,” to Teen Titans. I have not been able to identify any specific motifs appropriated from Teen Titans in the “VietCongs” comic, but the blonde with the wavy hairdo inside the circular panel on the page where the Cong gear up might be Kid Flash, who reappears on the same page, bottom right, crying "All the outfits are too small for me!" The English line “Blimey! He’s got blinkin’ metal hands!” does not appear in Teen Titans from these years, and “I was not only a circus India rubber man like you” sounds more like a song lyric. Yet it is possible if not probable that the messy shoot-up sequences in “VietCongs” was inspired in part by Nick Cardy’s panels depicting the Titans finally crashing the Mad Mod’s gig.

Why do I think that? Not simply because the scene’s irregular layouts and zooming speed lines seem precisely like the kind of things that would have nabbed Shinohara’s action-sensitive attention. There’s a specific swipe: the climatic image of Holley Hip smashing the Mad Mod over the head with his guitar serves as the organizing centerpiece of The Vietcongs Do the Ginza, much enlarged and dramatized.

In recent years, Shinohara has been making large-scale paintings based on collages of panels xeroxed from popular manga like One Piece, Great Detective Conan (a.k.a. Case Closed), and Pro Golfer Saru. The roots of that practice would appear to be here, with the reinterpretation of the shifting scale, fractured space, and bombastic action of the American superhero comic in terms of a photomontage-like overlapping of emphatic text and heroic pictorial elements at varying scales. The result is a far cry from the cerebral appropriation of comics by Warhol or Lichtenstein, or the dispassionate superhero paintings of Mel Ramos. It is much closer to the exuberant and actively creative elaboration of cartoon bodies and supplementary visuals in the work of painters like Peter Saul and Tateishi Tiger.

Speaking of Peter Saul: he might be useful for comparison of another sort. Between 1966 and 1968, Saul was making large-scale, cartoony paintings about the Vietnam War, in his case viciously satirical, outwardly directed at American activities in Indochina rather than inwardly, like Shinohara, toward the bubbling counterculture at home. Most of Saul’s works on the subject show slobbering white and black G.I.’s chewing on sexually caricatured Vietnamese girls. The titles set the images in Saigon and Hanoi, but for some reason a couple have Fuji looming in the background. Even if Shinohara wasn’t in direct conversation with Saul’s work (though given his reading of American art magazines, there’s a remote chance that he was), the two were inhabiting a similar imaginative landscape.

Or were they? The VietCong works are a good example of why we cannot speak of Shinohara’s interest and participation in youth culture as subcultural or countercultural. Granted, dubbing an action team the VietCongs is a cheeky move in 1967, two years after the commencement of Rolling Thunder, sorties which were launched if not directly from American bases in Okinawa then often from American aircraft carriers whose home port was in Japan. The local anti-Vietnam War movement had become, by this point, a major presence in the street and in the media. But when I asked Shinohara recently if he cared about the Vietnam War, he responded, “Not all, I had no interest in politics. I was a late bloomer when it came to that.” Asked if this painting was some kind of commentary on the contradiction between American superheroes as representatives of world justice and what the United States was doing in Vietnam, he simply said, “That kind of interpretation was probably beyond me,” and then quickly changed the topic to his New York drawings of people boozing up and smashing bottles in Downtown dive bars, as if that – the party site, the hang-out, the place where the guy with unconventional clothes and hair accrues social cred – was what mattered in the VietCong works.

Wrapping up: I complained earlier that Shinohara’s work was plagued by explosive outbursts that leave little of value at the end. Given “VietCongs,” it would seem that Shinohara had at least explored a better energy policy after all. One might call it by the general name “figuration,” but we can be more specific: “cartooning,” a mode of figurative drawing that is able to store and release animated energies through hand-drawn lines, moving bodies, and narrative picture sequences. I am not saying Shinohara was a “cartoonist” in the professional sense, nor was he an amazing dabbler. The tranquilizing restraints of modernist abstraction sometimes got the better of his ability to animate, while his background as a painter and a performance artist kept him from sustaining narrative and figuration for anything longer than a spurt.

Nonetheless, throughout his Tokyo period, the varied recurrence of forms of expressive narrative drawing suggest that cartooning not only represented something abstractly to the artist – the image of American pop culture, for example, or the image of bombastic action, or emotive cliché – but that cartooning was itself courted as a technique capable of accessing pop culture while also channeling the energies of youthfulness in a more productive way. He did play, like the Pop artists, with the silliness and histrionics of comics, but so did most professional cartoonists by the mid-late '60s. Yet cartooning was also what Shinohara did, and what he still does. Or at least it is what he tried and still tries to do, despite the anarchic actionist in his genes. The result is something we might simply call “action cartooning,” a name that captures the two art historical currents that underwrite Shinohara’s figurative work, as well as the tension between explosive but dissipating action versus contained but driving figuration that sometimes makes his work sizzle and sometimes makes it fizzle.