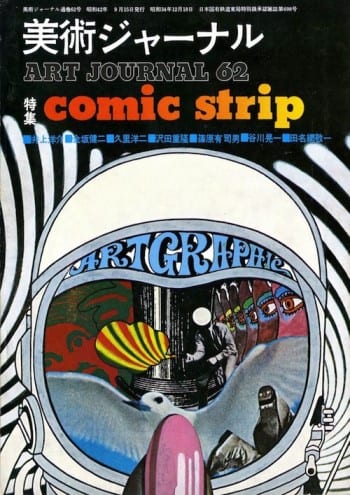

That’s what I thought, and still largely do. But then, this past fall while tripping through Japan, my colleague and grad school pal Hiroko Ikegami (with Reiko Tomii, co-curator of Shinohara Pops!, the Shinohara retrospective at SUNY New Paltz in 2012) blindsided me with this anomaly: Shinohara’s “VietCongs,” an experimental, 10-page comic for the magazine Bijutsu Journal (Art Journal), dated September 1967.

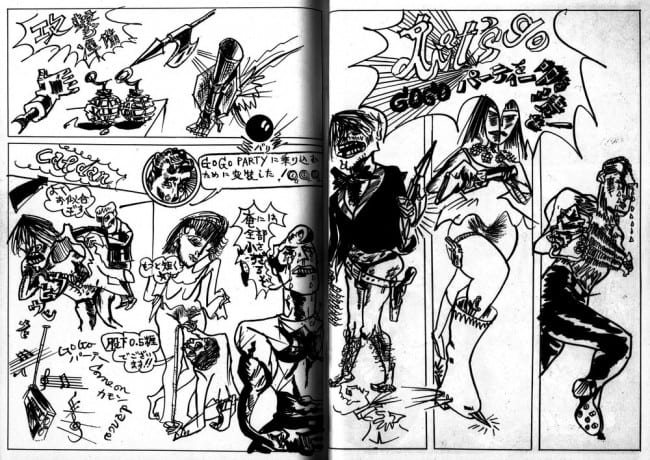

Luxuriate over the image. Does it not change the chronology of comics form? It has certainly made an impression on me. Shinohara’s paneled exercise in visual profanity really resembles nothing in Japanese comics until the advent of hetauma in the mid 1970s. There is certainly nothing like this in contemporary Garo, which despite its reputation for experimentation, generally steered away in the '60s from what was known at the time as “zen’ei manga,” avant-garde comics, what would probably be called today in English “experimental comics” or “art comics” versus the broader “alternative comics.” Whatever their challenges to conventions of graphic narrative, Sasaki Maki and Hayashi Seiichi (early Garo’s cutting edge in terms of aesthetic form) generally respected the standard multi-frame of the comics page, drawing craft, and the legibility of individual panels and figures. The closest thing in time and look might be Akatsuka Fujio’s graffiti gags in Tensai Bakabon circa 1970, or Tanioka Yasuji’s crass Metta meta gakidō kōza for Shōnen Magazine between 1970 and 1971. But those are rough approximations.

As I said, “VietCongs” was published in the September 1967 issue of Bijutsu Journal (Art Journal), commissioned for a special issue titled “Comic Strip.” One of the guest editors for this issue was Tana’ami Keiichi (b. 1936), the now-famous graphic designer, a friend of Shinohara’s since college and with whom he had been rooming since 1965. Though Shinohara was already attuned to youth culture, it’s likely that Tana’ami turned him on to comics, and particularly American comics.

Aside from reading Norakuro and Sazae san as a kid, Shinohara claims not to have been much interested in comics of any sort until the mid-late '60s. Tana’ami, on the other hand, apparently considered comics part of his personal identity. His debut book from 1966, A Portrait of Tana’ami Keiichi (Tana’ami Keiichi no shōzō) is dominated by hand-drawn but schematic images of Batman and Superman, arrayed in enlarged panel frames, set against landscapes sinuous but stagey (in a cardboard cutout way), or nested inside men’s sunglasses, next to the Stars and Stripes and Union Jack both. It’s a rather benign, rather decorative (in the sense of pleasing but meaningless), and also rather British (specifically Beatles a la Heinz Edelmann) interpretation of the American superhero – Carnaby Street does Gotham City. This, Tana’ami’s Mod-ish interpretation of Pop Americana, I suspect influenced Shinohara’s work as well. Though because of Shinohara’s jazz and rockabilly background, the results could not be more different.

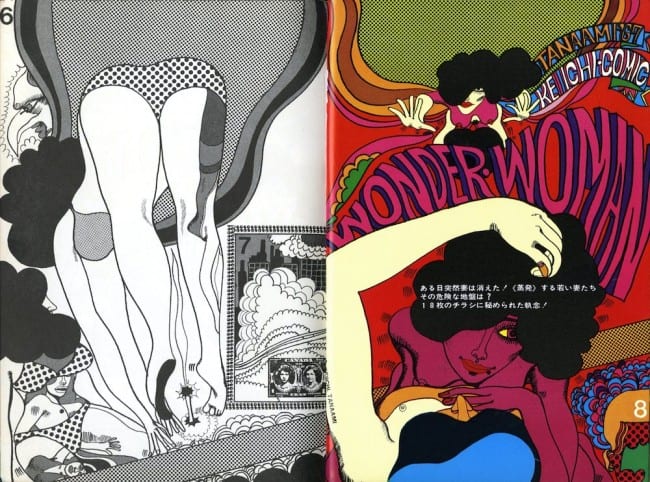

Of the contributions to the “Comic Strip” issue of Bijutsu Journal, Tana’ami’s “Wonder Woman” is probably the prettiest. Not so different from A Portrait, it stages the Amazon princess in a series of butt-up and breast-popping poses, flying and falling through the air. Batman also appears briefly. The piece is more polished than most of the rest of the magazine’s content. There are some lazy collages of kaijū and magazine ads by photographer and film critic Kanesaka Kenji, and by Inoue Yōichi and Kuri Yōji the kind of things that fell under “nonsense manga” in this era: adult humor manga and jazzy spot illustration moving in a non sequitur direction. Intriguing is (another college friend) Sawada Shigetaka’s rendition of one of Fredric Brown’s short science fiction stories, done in a wordy version of that traced photograph style exploited by the Situationists, Sasaki Maki, and other artists using comics to comment critically on mass media and entertainment in the age of television. Illustrator Tanikawa Kōichi created a quasi-narrative paneled piece depicting Pop-ified Maya gods engaged in various domestic and amorous activities.

It sure ain’t easy on the eye, but the only really stimulating work in the collection is Shinohara’s “VietCongs.” Not that there is much story to decipher anyway, but even what’s there is partially unintelligible due to the cacophony of the drawing. The stars are two guys and a girl. They can be very ugly, depending on the panel. Introduced as the “World Defense Army” (chikyū bōei gun) – a name evocative of the SDF-modeled teams in Japanese sci-fi entertainment – it is their assignment to put an end to the noise and debauchery of Japan’s Go-Go clubs (discotheques not strip clubs). “Let’s kill all those go-go shits,” says one of the Army, referring to the kids dancing and partying until they puke. To enter the club without raising a stir, the trio disguises themselves in hip clothing: one guy in thong and saloon gambler garb, the other as a bodybuilder, and she in a white dress (or is it see-through?) that fails to cover her fissioning crotch. They blam and slash their way through the club, the images get increasingly bigger and messier, the lines going from scratch to stroke to bleed. It ends with them toasting “the end of go-go and the coming of the new star trio, the VietCongs!!”

As I was casting around for a visual example of a Go-Go club from this period, Steve Ridgely came through again for me: the first Gamera (1965). Daiei’s answer to Godzilla was made a couple years before Shinohara’s comic. With pop cultural fads changing as fast as they do, it’s not a perfect match. But it provides a basic helping image. And, as Shinohara did in "VietCongs," it introduces hipsterdom only to destroy it.

The movie (go to 51:00): Gamera, a gigantic fire-breathing bipedal tortoise with tusks, has been awoken from suspended animation in the arctic by a nuclear blast. He arrives, after a time, in Japan seeking to consume, as personal fuel, the country’s energy resources. After various failed attempts to fell the beast at the country’s shoreline in the north, Gamera flies (by retracting his limbs and head and spinning in the air) and lands in Tokyo. His deafening welcoming roar bleeds into the sound of a drum beat and a close-up of a man playing guitar, running his fingers up the instrument’s neck, the heavy reverb an echo of the monster’s horrifying announcement that he has come to flatten the city. The band kicks into an instrumental surf number. On the dance floor are clean young adults in light sweaters, collared shirts, pressed slacks and skirts, and shiny leather shoes. While they bop and lurch, in through the front door of “Club Beat Beat” charge the police to tell them to evacuate. “We don’t care about our lives,” says a boy to the police. “To hell with Gamera! There’s no reason to stop the music. Dance!” To which the police chief pleads, “You should think of your family and parents!,” his voice drowned out by the music. Once the ceiling begins to collapse on their underground hang-out, only then do the kids bolt squealing.

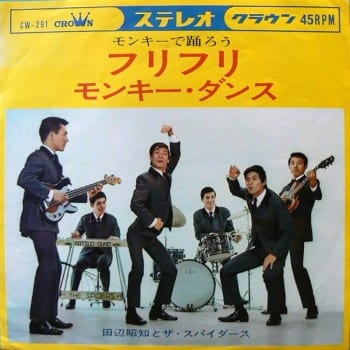

My grasp of Japanese pop music is tentative. But I believe that what is being seen in Gamera is an imitation of a band called The Blue Jeans, representatives of the so-called “Ereki buumu,” “The Electric [Guitar] Boom.” Sandwiched in between the rockabilly craze and the more ballad-oriented Group Sounds period, the Electric Boom was inspired strongly by The Ventures, infusing their surf sound with some distinct rockabilly elements. The Spiders were another popular band in this category. A number of their songs have the term “go-go” in them.

Even a Nikkatsu film was made with The Spiders in it: Youth a Go-Go (Seishun a gō gō, March 1966). Inspired by a popular battle-of-the-bands television program on Fuji TV, the movie tells the story of five former high school friends who, after seeing The Spiders perform in a jazz café, decide to start their own “ereki” band called Young and Fresh. They are hounded from practice space to practice space because of the intolerable racket they make, before finding an abandoned church in which to hone their skills. Once joined by a cute female lead singer, they compete against other bands and win the Go Go Festival ’66. The year before, Tōhō released a similar film in its Leader of the Pack (Wakadaishō) comedy series: Ereki no wakadaishō, the official English title of which was Campus A-Go-Go. The music numbers were backed by The Blue Jeans; ereki and “go-go” were a set.

By the time Shinohara created “VietCongs,” the Electric Boom had given way to Group Sounds. Groups that fall into this category were inspired generally by the new British sound with strong elements of Japanese kayōkyoku pop. When the musicians weren’t dressed neatly like Mods, they wore spangles and messy mops.

Despite the sweetness of most of the songs, there are some GS tracks with a strain of the harder and louder R&B line pursued by The Rolling Stones, The Animals, and The Who – for example, The Blue Comets’ “Blue Eyes” (“Aoi hitomi,” March 1966), which was originally released in English. When the Beatles played Tokyo in June-July 1966, The Blue Comets were amongst the opening acts. And like its British models, Group Sounds too shrugged off its share of adult disdain. There were the swooning teenage girls. There were accusations of “noise pollution” (sōon) because of the electric instruments and amplification.

Even by contemporary pop standards, however, most of the songs are sickly sweet. They exploit the usual themes of adolescent crushes and lovesickness. But as critic and former Garo columnist Ueno Kōshi (b. 1941) pointed out, looking back at Group Sounds from the 1980s, the world rendered was not only juvenile. Going as far as lyrics about cute little girls sadly clutching their dolls, the genre could be downright infantile. “Even considering that they were made primarily with teenage girls in mind,” wrote Ueno, “the songs were hopelessly childish.” This was, for Ueno, the watershed arrival of the sentiments of shōjo culture into Japanese pop music, which until then had sung almost exclusively about adult experiences. And it was no accident, added Ueno, that the ascension of Group Sounds in 1966-67 coincided with the explosion of story manga (until then primarily for kids and teens) as mass entertainment for young men and women alike. In England and the United States as well, after the mid 60s it is no longer possible to speak of pop culture independently of youth culture. Shinohara’s work from the late 60s is very much plugged into this shift.

Like Shinohara, Ueno was a rockabilly and modern jazz devotee. I mention this because I think the violence in “VietCongs” might be read, not just as an extension of Shinohara’s penchant for destructive action, but in line with the dislike expressed in Ueno’s review of Group Sounds. In Shinohara’s case, this dislike comes out as good-natured disgust.

On the title page of “VietCongs” (a simulated comic book cover that occurs three pages in), Shinohara refers, amongst an array of pop culture icons, to a famous Group Sounds single: former ereki band The Spiders’ “The Setting Sun Cries” (“Yūhi ga naiteiru,” September 1966). Nikkatsu, always eager to capitalize on youth culture, made a movie of the same name the following year. More kayōkyoku folk than an expression of the British Invasion, the first verse of “The Setting Sun Cries” goes, very slowly: “The setting sun / over the sea the setting sun / the bright red / it is the color of saying farewell / I’ve fallen in love with someone / I’ve fallen in passionate love / the setting sun cries for me.” On Shinohara’s “VietCongs” cover, the speech balloon reads, a little more emphatically, “The setting sun is crying!” Nude but for briefs, a six-string strapped to his back, his hair hacked into an ugly haystack, and decapitated heads hanging from his hands, Shinohara’s VietCong is not your typical Group Sounds star, who when they weren’t wearing acceptable street clothes (like the turtle necks on the cover of “The Setting Sun Cries” single), often dressed like British Mods or in ridiculous British Flower Power period costumes. Of course, nor is Shinohara’s gremlin your typical Vietnamese NLF soldier.

I will move on to the many comic book elements on the cover of “VietCongs” in a moment. But staying with the musical references: the cartouche on the right includes amongst the comics’ stars The Walker Brothers and P.P.M. – Peter, Paul, and Mary, presumably. The Walker Brothers did some mod rock standards, like “Land of a Thousand Dances,” which was also released in Japan. But generally they, like Peter, Paul, and Mary, represent a sweeter sound that is quite in contrast to Shinohara’s angry drawing, but within the range of the softer Group Sounds numbers.

The Walker Brothers, following in the footsteps of other foreign bands, had played in Japan in 1966 (and would so again in 1968). Peter, Paul, and Mary visited in 1967, so Shinohara’s listing of them could be topical. The Spiders were an all male seven-piece. But the two American groups named were both trios, like Shinohara’s VietCongs. P.P.M. were male-male-female, like the VietCongs. There were Group Sounds bands with animalistic names: the Tigers, The Jaguars, The Tempters, The Wild Ones. Shinohara has gone them a couple of steps further, hitting on what a band like The Fugs had already discovered, and what punk and no-wave bands like The Sex Pistols, Dead Kennedys, and Teenage Jesus and the Jerks would later exploit to no end: the uncouth group name as an immediate and overstated symbol of social dissent.

If this is counterculture, however, it is of a very limited kind. As I will argue below, if pop youth cultures defined themselves by converting “revolt into style,” so Shinohara is likewise turning the Vietnam War and the American superhero comic into an artwork that might be visually edgy but of zero political import. This is why I thought it relevant to mention that Ueno Kōshi, like Shinohara, was a rockabilly and “danmo” fan. What we might be seeing in “VietCongs” is the expression of that characteristic phenomenon of fandom: the symbolic trashing of one phase of taste by another. Or perhaps, given the changing gender coordinates of pop music at the time, “VietCongs” depicts a macho rock and hard bop attack upon on the shōjo-friendly Group Sounds. Or, given the same, it offers an ironic depiction of a Group Sounds band, imagined with a name more aggressive than a record company would ever allow, fueled by a spirit of violent direct action when the music was about nothing more threatening than heartthrobs, heartbreaks, and dancing.

Or are the VietCongs a righteous superhero squad called on to cleanse the country of juvenile delinquents? That is, after all, how they are introduced into the comic, and remember that Gamera had already used a similar conceit. “Cleanse the world of these anarchic go-go parties,” they are ordered by a godly voice in the beginning. Let’s not forget to factor in American comics. With its panel frames, speech balloons, and recognizable narrative, “VietCongs” is the most comic book-like contribution to the “Comic Strip” issue of Bijutsu Journal. Reference to American comics is overt. Batman’s logo appears on the faux cover, as does a flying (and burning) Superman, inscribed with Shinohara’s name. At left, a rainbow wheel of circles is captioned “Bat phone.” In the comic itself, American sound effects are many. The rendering of Japanese onomatopoeia (“GABO,” the sound of barfing) in the same Americanese is touching.

Of course, given Pop Art and Pop Design’s inclinations, none of this is particularly original. Professional manga authors had regularly cited American comic book effects since the Occupation. The joke had more or less worn off by the late 50s, when the influence of Pop camp provided it a restricted second life. But graphically, “VietCongs” is truly unique. It has the fast-action drawing that Shinohara would later use in The Avant-Garde Road, but without the Neo Dada and Pop collage elements that flesh out the compositions. The chaotic line-work seems a natural extension of his degenerated jazz imagery of the late 50s, and more recently (though I cannot go into this period of his career here) his messy renditions of late Edo woodblock prints and kabuki from the mid 60s. Still, with “VietCongs,” Shinohara has pushed deskilling (he was an art student, he knew how to draw) over the line, past primitivism, breaking with his rubbery Beat and Hard Bop past, and prophesizing punk and hetauma aesthetics a decade before their time.

What to call this style without being anachronistic? It’s certainly not Pop Art, though – in honor of Shinohara’s love of music and Ikegami and Tomii’s Shinohara Pops! – one might regard it a kind of “Pops Art.” Electric guitars appear aplenty in “VietCongs,” including on the comic’s pseudo-cover. The entire thing is set in a music club. The base drawing style itself has musical associations, or at least did so originally in the 50s. How about Mod Comics? Given the noise-flirting amplification of music clubs at this time, how about Ereki Manga? Electric Guitar Comics? Fuzz Comics? Sōon (Noise Pollution) Manga? Given Shinohara’s energetic personality, Go-Go Comics would seem workable if the connotations of the name were scruffier.

(cont'd)