In my long-ago youth, Sheldon Mayer was one of my favorite cartoonists. I was aware that he was also an editor of All-American Comics, Flash comics, and All-Star comics. This latter title introduced the first superhero team, the Justice Society. It included the likes of the Flash, the Green Lantern, the Spectre, etc.

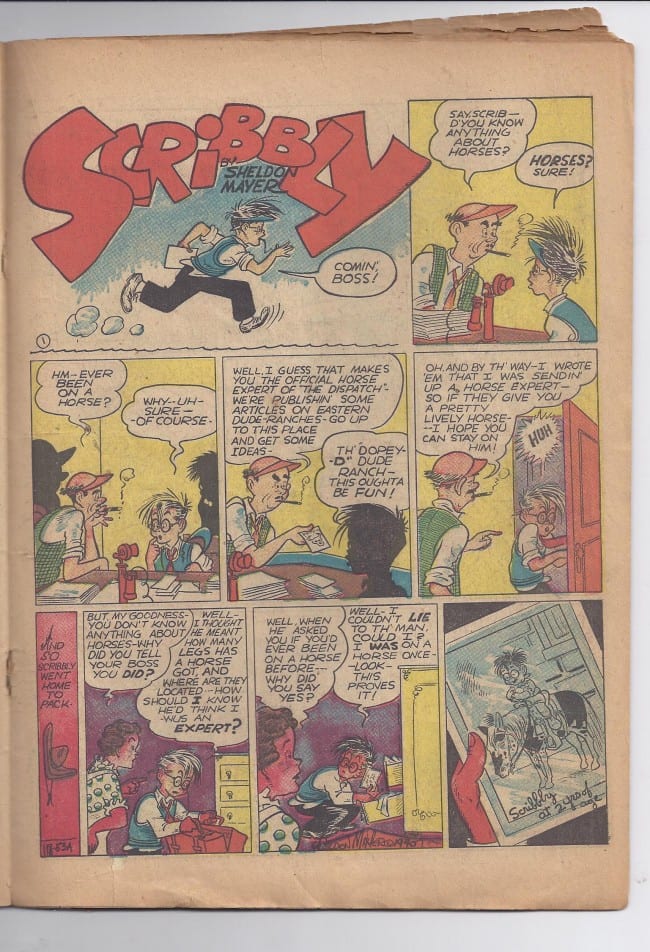

But I was most enthusiastic about Scribbly, the feature he drew for All-American. Scribbly Jibbet was a boy cartoonist, as was Mayer, who’d working professionally since his teens. Born in East Harlem in 1917, “a rough, tough neighborhood in those days,” he wanted to get out of there as soon as he could and cartooning was the way he chose. Scribbly, then, was his way of escaping. Mayer maintained that the strip was a blend of autobiography and fantasy, and the elements that seemed most true were the most unreal.

Mayer drew in a style that was appealing, quirky, exuberant, and, yes, scribbly. It also betrayed his fondness for some of the newspaper cartoonists of his youth, particularly Billy DeBeck and Rube Goldberg. I had been a boy cartoonist since about the age of 4, so I figured I had a lot in common with him. Therefore, in the middle 1940s, I wrote him a fan letter. I requested only his autograph, but I was hoping he’d toss in an original of Scribbly. But Mayer never answered me, and I never got a letter from him until 1974.

Mayer drew in a style that was appealing, quirky, exuberant, and, yes, scribbly. It also betrayed his fondness for some of the newspaper cartoonists of his youth, particularly Billy DeBeck and Rube Goldberg. I had been a boy cartoonist since about the age of 4, so I figured I had a lot in common with him. Therefore, in the middle 1940s, I wrote him a fan letter. I requested only his autograph, but I was hoping he’d toss in an original of Scribbly. But Mayer never answered me, and I never got a letter from him until 1974.

That letter, which appears below, he sent when I was collecting information for my nonfiction book on comic strips in the 1930s, The Adventurous Decade. I’d asked him about the period in the late ’30s when he ghosted George Storm’s Bobby Thatcher newspaper strip. I was not simply a fanboy anymore, and Mayer, no longer editing, had mellowed some. He gives considerable information about working for Storm and about his own early career.

I later ran into Mayer at a couple of comics conventions, and we became pen-pals. He was doing Sugar and Spike for DC and seemingly enjoying himself a good deal. He was having fun with the Sugar and Spike comic book and reaching an audience of very young readers and also their parents, some of whom may’ve been old Scribbly buffs. In the late 1970s I started writing a science-fiction strip called Star Hawks for NEA. The artist was my Connecticut then-neighbor Gil Kane. Mayer had hired Gil when he was still in his teens, and when the strip started appearing in Mayer’s upstate New York local paper, he’d phone me and talk, in his gravely tough-guy voice, about the feature. Always an editor at heart, Mayer would give me advice for Gil, mostly about his interpretation of my copy. Then we’d get to talking about his days with M.C. Gaines and DC. He’d talk about staff members, about the ones who gave him a pain in the ass, about some long-ago secrets. A few times, about ten minutes after hanging up, he’d call back and say, “About that business I was talking about, don’t use it in any of your books. I don’t want to jeopardize my pension.”

A very good cartoonist and a very good editor, Sheldon Mayer died in 1991.