Gray Morrow was the legend that should’ve been, one of those rare and amazing artist’s artists who slipped between the cracks of popularity in the comics industry, his work imbibed imbued with the same magic that graced old Flash Gordon strips. Gray was a child of the Depression, his head constantly in the daily comic strips and movie serials, and that 1930s visual influence showed in all of his work.

Not only did Gray work for both Marvel and DC, but the cherry on top was his eighteen year stint drawing a character near and dear to him: Tarzan. Getting to draw one of his childhood favorites didn’t get Morrow the industry-wide recognition the comics industry had denied him, but it was a dream job that went away when his health became nightmarish.

I never met Gray Morrow.

The time I did meet Gray? November, 2000, in his A-frame cabin in the woods of Pennsylvania, at his “Scottish Wake”. Pocho, his widow, had welcomed me into her home to celebrate Gray’s life with a cabin full of cigarette (and pipe) smoke, drinks, and plenty of cartoonist pals of Gray’s. Angelo Torres was there, as was Alan Weiss, Larry Hama, Ernie Colon, Don Kraar, and Frank Cho. Even Jim Steranko was there, decked out in his trademark pompadour and black clothing.

Gray’s ashes were placed in a Scotch decanter, his favorite pipe tobacco stuffed in the bottom by Pocho. That’s the closest I came to meeting him in a physical sense, the rest was through his friends and (especially) Pocho while writing a tribute article for Comic Book Artist magazine.

Dwight Graydon Morrow was born in Indiana in 1934, and was the perfect age to embrace the tail end of the movie swashbucklers, radio shows, and serial heroes. His father was a veterinarian who also owned a riding academy, allowing Gray to live out his cowboy dreams while working as a teenager for $13 a week.

After graduation high school in the ‘50s, Gray made his way to Chicago and then New York, where he became friendly with several of the best cartoonists of the time—Wally Wood, Roy Krenkel, Frank Robbins, and his close friend Angelo Torres. When Gray’s stint in Korea ended in 1958, he broke in through Cracked magazine, Classics Illustrated, and some Western stories at Atlas Comics (the future Marvel).

It was a tragic matter of too little, too late, as Gray came in right at the tail end of things, missing his chance to firmly establish himself in the now dying industry. Comics were not only suffering from a post-war sales slump, but were also under attack by parental groups and Senator Estes Kefauver. With psychiatrist Fredric Wertham (who had written an inflammatory book on comics’ effect on children called Seduction of the Innocent) fanning the flames, Kefauver’s televised Senate hearings on comics were the final nail in the industry’s collective coffin. With publishers and distributors dropping like flies, there were less places for Morrow to exercise his illustrative chops.

Had Morrow popped up just a matter of years earlier, there’s a chance we’d now speak of him as a contemporary of the EC crowd—along with Jack Davis, Harvey Kurtzman, Bernie Krigstein, and Johnny Craig. As it was, Gray Morrow has become an “artist’s artist,” known mainly to the finer comic artists, as well as those more versed in comics history than the average fan.

Morrow did manage to find work outside of the comics industry, illustrating science fiction paperback covers, as well as B-movie posters. In the ‘60s, he worked alongside animator Ralph Bakshi on the Spider-Man cartoon as art director for the schmaltzy animated translation of the comic. Morrow also contributed heavily to the Warren line of horror magazines Eerie and Creepy, giving a glimpse of what a Morrow working on the EC horror line might have been.

Publisher James Warren, a fan of the defunct EC Comics line of horror books from the prior decade (including Tales from the Crypt), decided to bring that horror sentiment back to comics. In order to avoid the Comics Code censorship codes imposed on comic books at the time (which blatantly killed the horror genre for comics), he opted for a black and white magazine format—one that allowed him to feature mature material.

The gray-toned stories were rife with atmosphere, violence, and sex, giving Morrow and company free reign to create horror stories that were allowed to push the envelope in terms of both content and craftsmanship.

By the ‘70s, his comic book art was everywhere—from Marvel’s horror to DC’s supernatural Western El Diablo (about a ghostly masked gunfighter on a black horse, written by Robert Kanigher) to Archie Comics’ Red Circle horror line, which Gray also edited as the genre was welcome back in the comics industry due to a Code revision. The Red Circle line is another best-kept secret: Morrow recruited talent like Alex Toth and Angelo Torres to contribute relatively safe, yet still effective, horror stories.

One story in particular, embraces Morrow’s love of the pulps, as an author is possessed by the spirit of a murderous pulp vigilante clearly based off of the gun-toting Spider character of the 1930s and 1940s. In the last panel, the protagonist is about to take the only way out of his dilemma, as he pushes the nozzle muzzle of a pistol to his temple. Discovering the story in light of Morrow’s final fate makes the story even more chilling.

Although short-lived, the Red Circle books, Red Circle Sorcery and Mad House, are worth digging out of back issue bins.

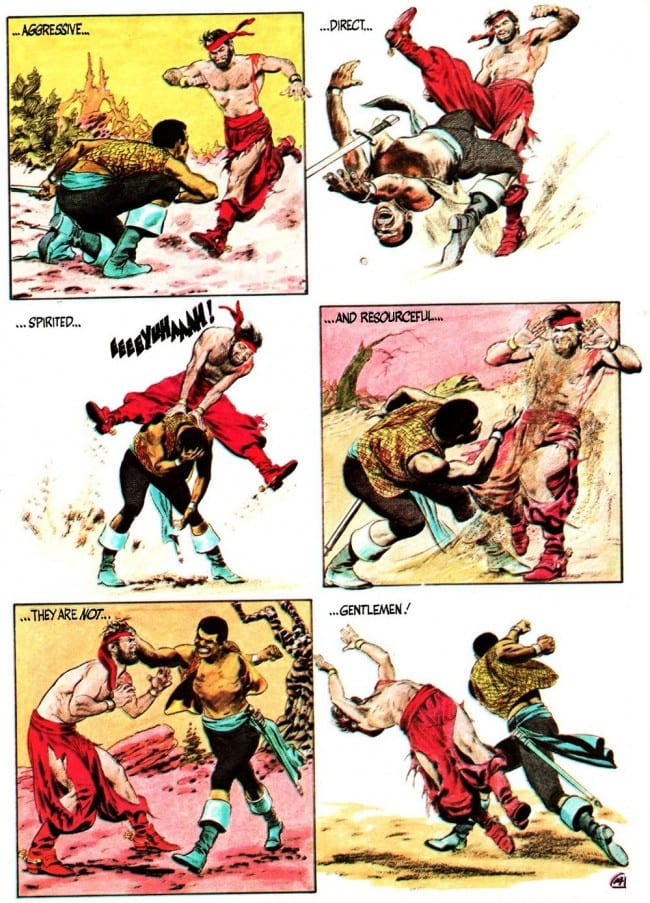

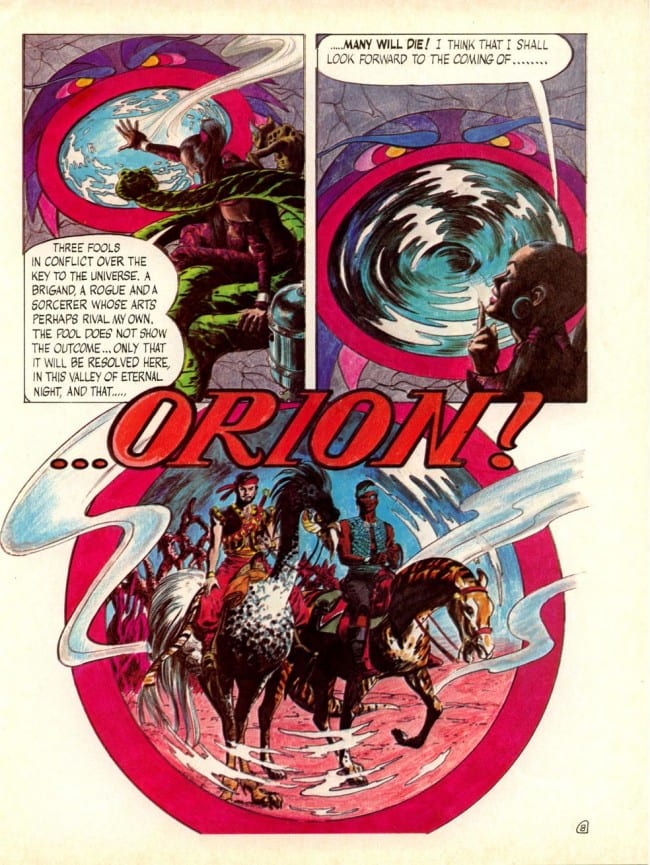

Gray Morrow’s most masterful work was Orion, a storyline that he created and published through Heavy Metal magazine in 1978, after Orion himself had debuted in 1967 issue of Wally Wood’s witzend #2. This sword-and-sorcery tale follows the quest of the rakish Orion and his enchanted sword Thorbolt, as he faces off against an evil wizard and sorceress. Fashioned in the mold of Errol Flynn, Orion is clearly Gray’s own fantasy cipher, his own escapism into fantasy, action, and beautiful women lovingly put down on paper. It wasn’t unusual for Gray to cast himself as his own protagonists: one look at the goateed El Diablo evokes images of the similar Morrow, and he was known to not only model for reference in full costume, but to even place himself (through the work of an Exacto blade and rubber cement) into stills from old Flash Gordon movie serials.

For his next creator-owned comic book, Edge of Chaos from 1983, Gray went the Steve Reeves route, creating a dashing and muscular hero modeled off the Hercules actor, rather than a swashbuckling Flynn type—one Eric Cleese, who is innocently sucked into a time not his own. The three-issue mini-series, along with Orion, is another of his most personal works.

1983 also saw the birth of what was to be a longtime association for Gray: a life-long fan of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ jungle hero, Gray started drawing the Tarzan Sunday strips.

Gray was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in the late 1990s, which caused tremors in his hands that left him unable to draw. By 2001, he had lost his job drawing Tarzan after eighteen years behind the board.

On the morning of November 6, Pocho left Gray while she ran her usual errands (which often included a stop at a used bookstore to grab a stack of paperbacks for him). He was dressed up, and she told him he looked set for a date. He told her, yes, he did have a date.

When she came home a bit later, he had left a note for her, detailing his not wanting to burden her with having to take care of him and written in clean block type. It was probably the result of him painstakingly controlling the hand tremors that had ruined his career. After leaving it, Gray had gone into his bedroom, and shot himself through the temple with a revolver.

Morrow was a physical man, raised riding horses with plans of once becoming a movie cowboy (passing it up to become a comic book artist instead); he was also a dreamer, photographing himself in science fiction costumes and placing himself in stills from serials like Flash Gordon. Being a man’s man, and then losing the work he lived vicariously through, and needing to rely on his wife to take care of him, must have been devastating to his pride.

Pocho tells of the first time she went over to fix a “broken” light in Gray’s apartment: he hadn’t realized that it simply needed a new bulb. Before the Parkinson’s, she took care of him in so many ways, from changing more light bulbs to cooking his meals to buying him used books to read. Without the steady stream of work coming in (and the inability to further pursue the only thing he was professionally good at), on top of his illness taking away a chunk of his independence, Gray must have felt he’d let her down as both a husband and a man.

On a creative level, he must have felt crippled.

I wrote the article for CBA, and consider it a turning point in my career and my life as a writer. For the first time writing about comics, I was writing about an honest-to-God person, the enigmatic Gray Morrow – cartoonist, pipe smoker, Scotch drinker (his preference was for Dewar’s with slices of apple on the side)– and I did it all with a lump in my throat and an emotional drain by the end. The hardest part, the one I couldn’t write about then but can now, was imagining the emotional toll Pocho had gone through in losing her husband.

But luckily for Pocho Morrow, she’s a tough bird. A year after Gray’s death, she had to sell their fourteen-acre home (which they’d dubbed “Camelot”), and move into a much smaller house with her numerous cats and dog. It took her months to pack up everything from the house and studio, most of which went into storage.

Things, since then, have gotten progressively tougher for Pocho. She’s often had to sell Gray’s artwork off to pay her debts, and has literally been scraping by, working a series of jobs in the tiny village of Kunkletown. Despite all her hardships, she loves life, whether it’s a sunset, a grandson, or a glass of red wine.

And I both admire and love her for it.

We’ve talked about doing a book about Gray’s life (about before, and after, his death) for years. While Gray lacks a mainstream following, he is definitely the artist’s artist, his mastery of line and composition features a fluid subtlety that only an artist can really, truly acknowledge.

It was one of those instances where Pocho pulled out Gray’s artwork that we came across most of the original art for Orion. Hand-colored, the Orion originals are even more breathtaking in real life than they were in old issues of Heavy Metal, and we took them to Hermes Press to reprint in a new edition. Most of the pages were shot off of that original art, with the missing pages pulled from the well-printed Heavy Metal issues themselves.

Also included is Edge of Chaos; they’re two very different sides of the same coin, visually speaking—Orion is reflective of Gray’s more classical approach to inking, while Edge of Chaos is when he started to use a thinner ink line in his work—but both meet the same high watermark.

But even content-wise, as well, they differ: Orion is straightforward sword and sorcery, as Orion himself goes on a journey to defeat an evil sorcerer. Edge of Chaos features the time-displaced Eric Cleese as he takes down his own evil sorcerer for the Greek Gods (who are really just aliens living on the Earth of the past…very Chariots of the Gods type stuff), but amidst a mixing of odd Kirby-esque technology. Of the two, I prefer Orion, as it was done at the height of Morrow’s ability while Chaos has spontaneity to it that smacks of being done between projects.

The best description that I can think of is that Orion is like a Ray Harryhausen movie with topless women, while Edge of Chaos is what happens when He-Man gains an R rating.

Both stories are a glimpse into the influences and craft of comics’ own forgotten man, a masterful storyteller whose craft elevated whatever project he was working on, a man who is more than just a historical figure to me now, but the enigmatic ghost of a long-lost relative lost right before I came into the picture.

NOTE: This essay started as an introduction to that Hermes Press reprint edition that combines both Orion and Edge of Chaos, on sale now. I personally drove the Orion artwork several hours across Pennsylvania from Pocho’s small house to Hermes Press’ offices after selling them on this long-desired collection.

Hermes Press decided to not use my essay while still advertising its inclusion on their website, instead replacing it with one written by publisher Daniel Herman himself.They did, at least, give me an acknowledgement for introducing them to Pocho within the book, and I’m looking forward to them sending me a copy of the collection.

I strongly urge you to pick the paperback edition up: Hermes had the best art to shoot off of for reproduction, and a portion of the proceeds are slated to go to Pocho Morrow. It is also the first chance in thirty years to own what is, in my opinion, the long-forgotten work of a mostly forgotten master.