In the fall of 2012, I spent some time doing research at the Gordon W. Prange Collection at the University of Maryland, College Park, near where my mother lives and where I passed my teenage years. As you may know, this is the largest collection of printed matter from the Allied Occupation of Japan anywhere in the world.

Dr. Prange was a professor of Japanese history at UMD and author of best-selling books on World War II. His study of Pearl Harbor, for example, was adapted into the Hollywood movie Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970). Between 1945 and 1951, for almost the entire duration of the Occupation, Prange was stationed in Japan. From 1946 to 1951, he led MacArthur’s large historical staff, and focused on preparing the General’s multi-volume report on the Pacific War. When the Civil Censorship Detachment ceased operations in September 1949, Prange recognized the importance of their files – ostensibly a copy of every book, magazine, newspaper, and press photograph published in postwar Japan between 1945 and 1949 – and was given permission to ship the entire collection (500 large wooden crates) to his home institution in College Park.

For anyone studying the Occupation, the Prange Collection is an inexhaustible treasure trove. For me, interested in the impact of American culture on Japanese manga, I cannot imagine research without this resource. There are reportedly 8000 children’s books in the collection, 2069 of which are manga. This does not include the manga in magazines (children’s or adult), which are a separate category. Some of the background research on Sugiura Shigeru for The Last of the Mohicans was conducted at UMD (two of the images in the essay are from the Prange). There are a couple of Sugiura titles at the Prange that do not even appear in the master list in the Mitaka City Catalogue (2002), the most complete resource on the artist.

For The Mysterious Underground Men essay, I used the Prange to learn more about the era’s science fiction. Actually, the original intention had been to use the copy of The Mysterious Underground Men at the Prange to make our archival edition, since all the children’s books have been scanned at publication-quality resolution. It was thus a surprise to be told that the Prange did not own that specific title. Not only that title, they also do not own two other major Tezuka books, New Treasure Island (1947) and King Kong (1947). They are also missing Hello Manga (1946-47), the Sakai Shichima-edited magazine that published some of Tezuka’s first strips. Other books by the same publisher from the same year are there, but why not these? Did publishers find a way to circumvent the CCD? Did books get lost accidentally during packing, shipping, and storage?

This article is actually about a different omission. When I first started using the Prange, I was asked to watch a tutorial video about the collection. There were some clips from the Occupation period. One of them shows a Japanese boy and a Japanese man, if I remember correctly, reading an American comic book while sitting on the curb. The footage, I am told, came from the National Archives, also located in College Park. I have not bothered yet to hunt it down, though some day I will. The Prange has an amazing collection of press photographs, and I assumed that they must have similar images. But the curators could recall no such item, and within the subject categories under which the photographs are listed, there is no entry for comic books. Look at any twelve manga in the Prange collection and you are likely to find concrete evidence of the influence of American comics. But how great it would be to have an image of Japanese actually reading them!

Research works in mysterious ways. Mom wanted me to go with her to visit an old friend near Baltimore, who had spent some time working in Japan during the Occupation. Her name is Leora Smith. She goes by Lee. She is a sharp 92-year old. I grumbled on the ride up, pouting because I had better things to do. But how glad I am that I went. Lee wanted me to look at some of the art d’objets she had picked up in Japan, tell her a bit about their history, and estimate their worth. The Tsuchiya Kōitsu prints from the 1920s-40s were quite nice, but only curators and dealers can really discern between tourist curio and genuine antique when it comes to ceramics, dolls, and ivory and jade jewelry. Then she showed me some photographs she took while stationed in Japan, the first time between 1947-48 in Yokohama, the second time in Kure (near Hiroshima) between 1950-51. Under the title Memories of Japan: 1947-1951, she has published a selection of the photographs as a print-on-demand book through Apple.

There are landscape shots, cityscapes, images of the Fujiya Hotel in Hakone, farmers, itinerant performers, schoolrooms, crowded trains, playing children, cottage industries, and so on. Lee was trained as a photographer in art school in the 1940s, so the composition and printing are quite nice. Some of the pictures, like the one above with a boy passing a repaired shop window in Odawara, I can imagine appearing in Ars Camera or other photography magazines of the early postwar period with robust amateur sections. The tones and the semi-abstraction of the dotted line of white tape – almost like an animated insert – reward repeated viewing. Behind the boy, interestingly, are the kinds of objects expats were likely to buy, as if Lee herself, with her small collection, was reflected figuratively in that patched pane. Meanwhile, the average historian might be intrigued by the few cityscapes and depictions of education and industry in Lee’s book. This one, shot near Hiroshima, would be fine gracing the cover of a book about popular entertainments.

And for the manga historian, especially for the manga historian looking for pictures of Japanese reading American comics during the Occupation, there is this wonderful surprise present from Christmas 1950, showing a kid from Hiroshima intently reading a copy of the premier “true crime” comic, Crime Does Not Pay.

Click on the image for a closer look.

When historians find old photographs that seem useful for illustrative purposes, they are often handicapped by lack of data concerning their shooting. But here was the photographer herself sitting next to me, who despite being a nonagenarian recalls her time in Japan sixty-plus years ago in lucid detail. Between 1950-51, her second stint in the country, Lee worked as a secretary for the Public Health and Welfare Section of the US Army Civil Affairs Division. Her team was stationed in Kure, a major naval seaport with extensive shipbuilding facilities (the battleship Yamato was built in Kure) some 10-15 miles down the coast from Hiroshima. As elsewhere in Japan, the primary health concern in the region was tuberculosis. Japanese hospitals had no nurses, recalls Lee. As a result, there was no choice but for TB patients to convalesce at home – a disastrous situation for families and crowded communities due to the contagiousness of the disease. Lee’s team was charged with caring for the sick and for public education about the disease, culminating in a major handbook on tuberculosis in Japanese, authored by one Dr. Barrett.

A cartoon-worthy aside: the veterinarian on their crew aided the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission, the controversial ABCC, which was tasked with studying the effects of radiation on atomic bomb survivors. The veterinarian’s assignment was to study Hiroshima’s animals. Lee recalls being told that chickens survived the holocaust (if they weren’t killed by the blast, of course) reportedly because they lack lymph nodes. True or not, it’s strange even as fiction.

As for the comic book photograph: Public Health and Welfare was involved in various activities of a less medical sort. This photograph was shot at a Christmas party held in Kure for kids from an orphanage in Hiroshima. The exact location, Lee thinks, was the mess hall at Kure or one of the CAD staff houses. In her book, she includes the following in the caption: “Popcorn and Coke were treats they enjoyed and comic books were a source of great entertainment.” Witness the famed “chewing gum and chocolate” in action, but not out of the back of a jeep. Were Christmas parties and comic books also tools in that goodwill mission? Lee herself did not participate in the organization of the depicted event. The photograph, shot on a 4x5 Graflex Speed Graphic, was taken for her own amusement, not on assignment. Asked whether she recalls if comic books were handed out on other occasions, she says no. She thinks even this copy of Crime Does Not Pay was probably just something that a CAD staff member or a GI had left sitting in the room in which the party was held.

It’s ironic, nonetheless, that of all the comics in circulation, the boy should be reading this one, especially at a function designed to uplift orphans’ lives (even if just for a day) and introduce them to the delights of American affluence. For Crime Does Not Pay, the industry’s best-selling title in the forties (in the vicinity of three million copies a month), was, as far as mainstream blueblood America was concerned, the very worst kind of comic book. Not that the public knew this, but it was run by some shady alcoholic characters and distributed by mobsters. The founding publisher, Lev Gleason, was brought before the House Un-American Activities Commission in 1946 for his anti-fascist and leftist associations. Much worse, the magazine was filled with drugs, sex, and violence. Despite its ostensible anti-crime stance, it was the kind of title that anti-comics crusaders like Fredric Wertham condemned as a major cause of juvenile delinquency. In Seduction of the Innocent, published in 1954 but based on articles written since the late 40s, Wertham wrote, after singling out Crime Does not Pay by name: “Children know that in quite a number of crime comic books there is in the title some reference to punishment. But they also know that just as that very reference is in small letters and inconspicuous color, the parts of the title that really count are in huge, eye-catching type and clear sharp colors: CRIME; CRIMINALS; MURDER; LAW BREAKERS; GUNS; etc. The result of this is, of course, that when comic books are on display only the crime and not the punishment is visible.”

Presumably this Hiroshima boy was not able to read English, so he would have been spared the mixed messages on the comic book’s cover. But still he had eyes, and while I don't think it wise to read too much into snapshot expressions, one can safely describe this one as “glued.” What exactly is he looking at? I am having trouble positively identifying the specific issue, but I think (considering the light-colored title, the star at left beneath the seductively big C, and the pale area in the top right of the graphic) that it’s Crime Does Not Pay no. 93 (November 1950). The date would be just right, of course, given that this is a photo from Christmas 1950 – which would also mean that American comics got to Japan very quickly after their release in the United States. Unfortunately the Digital Comics Museum doesn’t have this one archived . . . anyone? I want to see what that kid sees. Presumably it is something that fits the following description, lodged by a comics-hating doctor with the Canadian House of Commons, and cited by Wertham: “the kind of magazine, forty or fifty pages of which portray nothing but scenes illustrating the commission of crimes of violence with every kind of horror that the mind of man can conceive.”

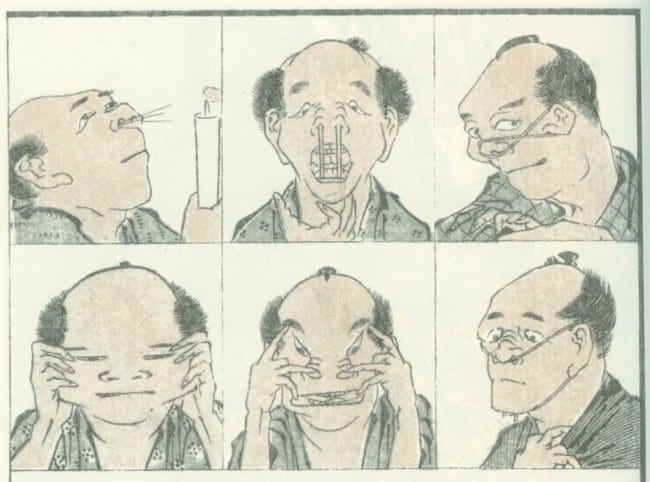

What makes Lee’s photograph more than a valuable historical document is what's bubbling around the comic book. Here are these orphans, five years after the war, being pumped full of sugar by their American families-for-the-day. The range of expressions is superb. On one end of the couch, a kid is immersed in a trashy comic book. On the other end, an older boy looks a little sickly and decidedly unbuoyed by the festivities. And in the middle – how fantastic for a photograph with a comic book – the youngest boy entertains himself with a string, maybe from the cellophane-wrapped Christmas goodies on the table, positioning it as if he is about to crane his nose upward into a snout . . . as if he had read Hokusai Manga!

What makes Lee’s photograph more than a valuable historical document is what's bubbling around the comic book. Here are these orphans, five years after the war, being pumped full of sugar by their American families-for-the-day. The range of expressions is superb. On one end of the couch, a kid is immersed in a trashy comic book. On the other end, an older boy looks a little sickly and decidedly unbuoyed by the festivities. And in the middle – how fantastic for a photograph with a comic book – the youngest boy entertains himself with a string, maybe from the cellophane-wrapped Christmas goodies on the table, positioning it as if he is about to crane his nose upward into a snout . . . as if he had read Hokusai Manga!

That’s a joke. But I wonder if this photograph and the contrast between the two kids’ demeanors can’t be exploited as a cipher for changes taking place in Japanese comics culture at the time. The anti-comics movement in Japan, while making loud noises since the 1930s, did not really take off until 1955. That’s not the history I am thinking about. Instead, in my mind are how entertainment was redefined in comics immediately before and soon after the end of the Occupation, and what those changes entailed in terms of the relationship between work and reader – whether comics were more likely to make them laugh or fret.

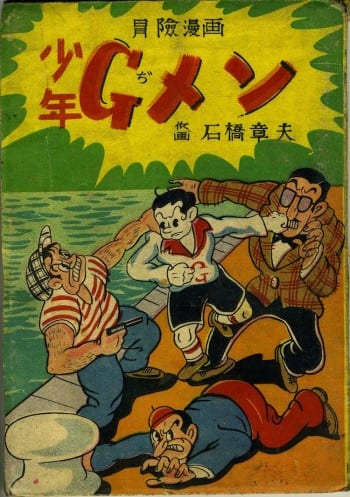

The rule of laughter over children’s manga, which was almost total even when it came to titles dealing with ostensibly heavy subjects like war or the adaptation of history and literary classics, was rapidly being usurped by adventure and mystery comics focused more on action and suspense. These latter were heavily influenced by American superhero, crime, and horror comics brought to Japan by the Occupation. There were figures like Sugiura Shigeru, a best-selling author in the 1950s, who absorbed that new wave through parodic citation and spoof. Tezuka Osamu represented the inverse. He integrated the older humor model (which itself was partially rooted in American cartooning, movies, and animation) within the new action and suspense mode, which he himself helped polish and popularize through his akahon of the postwar 40s.

Tezuka’s first magazine serials appeared in 1950, not long before Lee took her photograph. This marked not only Tezuka’s personal arrival into the mainstream of children’s publishing in Tokyo, but also that of a new comics reading experience. His work instituted a method of captivating the child through a combination of multidimensional characterization, speedy narrative development, dynamic breakdowns, explosive physical action, soaring fantasy – but also laughter. The two kids together – furrowed brow plus silly snout – thus figure Tezuka. The photograph, as I said, was taken in the artist’s coming-out year.

The comics-reader alone, meanwhile, represents the seed of developments that would transform manga so completely in the following years that even Tezuka feared obsolescence. The action and suspense mode that became known in the mid 50s as gekiga was rooted, in many of Tezuka’s techniques for sure, but more directly in the judo manga of Fukui Ei’ichi, earnestly focused on the psychological tension and physical dynamism of the martial arts contest. In the mid 50s, Matsumoto Masahiko would adapt Fukui’s aesthetic to locked-room mysteries. Tatsumi, partially under the influence of American comics, would further elaborate Matsumoto’s aesthetic in the direction of fast-paced action and expressive drawing, away from crime detection and towards thrillers. Already by the late 50s, Tatsumi was claiming in writing that gekiga – the name he coined for this new style – intentionally set out to break with the dominance of humor and especially slapstick in manga. The expulsion (which was not always complete in practice) aimed to clear room not only for more serious and gritty content, but also for intensified feelings of excitement, suspense, and horror. Accordingly, one of gekiga’s leitmotifs was the wide-open eye: witnessing a crime, anxiously awaiting death, attentively watching a threat. It presumed a reader that was similarly transfixed. (I recently published an article in IJOCA (Fall 2013) on this topic, if you are interested.)

The impression Crime Does Not Pay made on this Hiroshima boy might have lasted no more than a few seconds. But the kind of material he was reading would eventually find its way into the hands of impressionable young wannabe artists like Tatsumi, Saitō Takao, and their colleague at Hinomaru Bunko and later in the Gekiga Studio, Yamamori Susumu – as well as their elder peer in Tokyo, Mizuki Shigeru – and help guide them in creating comics designed specifically to engender the type of engrossed and disconcerting reading experience that one glimpses in Lee’s photograph. This kid might thus be seen as the proto-gekiga reader, some five-six years before the style’s maturation. And, as the gekiga artists would eschew slapstick for suspense and horror, so too our prophetic orphan is too mesmerized by scintillating depictions of crime to notice the classical cartoon by his side . . . or so a reading might go if we burden the photograph with maybe more history than it contains.

I close with classifieds: Do you have family that was stationed in Japan during the Occupation or after the Occupation in the 50s, and do they have any photographs showing American comics? Also, not related to this post: Do you have family that was stationed in Japan during the Occupation and had their portrait drawn by local artists, and if so is the portrait signed? Many painters and cartoonists did this to make a living. They talk about it in their reminisces, but few physical examples are known. Presumably most exited the country in the luggage of their sitters, perhaps stuffed side by side with the kind of artworks and antiques Lee owns.

That was probably the trade. Bring comics and other reading material over, in order to have American comforts to soften the culture shock of your tour of duty. Then leave that trash behind to make room for neat Oriental knickknacks when you head back home. The result: American arts got a little more Japanese, and Japanese comics got a lot more American.