ROBINSON: You take us through this 200-day process of David’s limited time on Earth, and apart from that tiny “bang,” his death up on his final work could just be his time running out. But you made a point, however subtle, that his time was cut short, that human agency rather than his deal with Death is what killed him. Why was that important to you?

MCCLOUD: That’s just the mechanics of the story, really. Having Meg die on his very last day would have seemed unnecessarily schematic. Originally, she died three days before his, because I misremembered the story of the real-life Meg, the premature baby that Ivy’s sister had long ago, where I got the character’s name from for various superstitious reasons. [This story is told in the The Sculptor’s postscript.] I had remembered her as living three days, but she lived only one day. I like the idea of him realizing she had three fewer days, but made better use of them. To me, that had a rightness to it. But if that’s going to happen, if he’s going to continue to live for three days, up to his last moment, that didn’t feel right. And the idea of him giving back time, which he had seen as so precious, that worked for me. He no longer cared about his own minutes, and would risk them the way he did. That felt like the proper transition for a character who had stopped caring about so many things, himself chief among them.

He’s still working on the sculpture when he’s shot, and from what we see of it, it might not be finished. It’s all raw girders at the ground. In your mind, is it essentially complete when he dies?

He more or less finished. You can see him placing his hands in a way that indicate he’s fine-tuning. He’s not making the big strokes anymore.

You said you don’t mean for his final work to come across as a masterpiece, though it’s hard to see that from the story.

No, I don’t. Though I don’t want to say one way or another. I don’t even think it’s an interesting question. [Laughter.] How it stands up as art is completely beside the point. He’s keeping a promise, and creating something that can’t be ignored in the bargain. But almost accidentally. Almost as a proxy for her.

The proxy aspect is bothersome. It feels like David’s trying to recreate Meg, as he has at so many other points in the story, for various reasons. And his last act is looping back to this thing he’s done multiple times in the past. It feels like after all the growth he’s been through, he still hasn’t learned much.

I don’t think that’s true. I think he’s learned quite a lot. But what he chooses to make—it’s two things. It’s her, and we’ve established that he has this preternatural memory for detail, so we hope he would have the chops to do this. That was important from the get-go. But in the end, all he can do is honor his promise to her. And what he chooses as an image is something from their recent past, when she’s outside St. Patrick’s cathedral, tossing the baby in the air. But it’s also about what she said to the baby in that scene. That’s his way of also acknowledging that it’s all down here.

It’s hard for me to explain why, for me, it feels like the right image. But I think he’s learned a lot. The only problem is that he can’t apply it all. He can’t apply the acceptance he’s learned, because that’s been taken away from him. I suppose he’s going to a smaller place inside his mind, of just being with her. It’s one last communion, one last message, one last interaction with her, almost to the point where she still exists for him. She’s still there, suspended in that moment. Something he’s been doing all along is to try to stop time, to stop the clock. This time he’s just stopping it on her. He knows he can’t bring her back. He can honor a commitment, he just can’t conjure her back to life, any more than Harry could. But he can at least, in his last moments, go back to a place where she’s still there.

The first time I read the book, I saw him as trying to conjure her back, and specifically as this angelic mother figure, holding up the child they never got to have. You mentioned the Pietà earlier, and here we’ve moved to the Madonna and Child image, which seems so sentimental on his part. It wasn’t until I re-read the book that I realized the image isn’t his unborn child, it’s someone else’s baby she was holding in that specific scene. It’s something he’s seen in the past rather than imagining in a future that never happened.

This is why what she says to the baby is important. That’s the overriding message. You say she’s being reduced to a Madonna-and-child image, but it’s not necessarily a reduction. This is something she had wanted. This does all relate to the fact that Ivy and I tried for four years to have kids. For Ivy, this weighed very heavily on her for some time. So some of my personal life is creeping in there too. But it bothers me that the image might be seen as reducing her to just that. So I hope readers remember that earlier scene with the baby, and what she’s saying there, which is meant as the overriding message.

But look. I was obviously worried about that too. I just knew the image had to be simple. I knew it had to be of her. And I had a pretty small selection to work from. [Laughter.] Because it couldn’t be very specific. I mean, it could be a big sculpture of her riding a bicycle, but what would that say? It had to be a singular image. So I didn’t necessarily have a huge number of choices there, unfortunately. I know what you’re talking about, and it was a concern, and that’s why the scene in front of St. Patrick’s cathedral. But who knows whether it was enough to forestall those thoughts on the part of the reader?

You’ve talked a lot in interviews about there being parallels and Easter eggs throughout the book, like the image of Meg with the baby being a scene from the protest. Are there others that strikes you as particularly important for the readers?

Well, I don’t want to spell them all out. I mentioned the crowd ring, and you’ll actually see other crowd rings throughout the book, and similar shapes. I’m interested in visual metaphors because they have a way of linking up that the cartoonist didn’t expect. For instance, the fact that Meg first enters as an angel is an inversion of Judeo-Christian mythology. The whole thing is turned around, turned on its head. And the fact that she’s wearing knee socks and a baseball jersey and a cocktail skirt becomes both very much about New York and very much about America, and how America has linked up with that brand of Judeo-Christian mythology. That wasn’t necessarily intentional. I was throwing symbols together, but the more I look at them, the more I see them reaching out to each other, and having a conversation. The fact that David’s grand-uncle Harry is based on my father-in-law, and both of my protagonists are Jewish—David has a Jewish mother, and both of Meg’s parents were Jewish—that calls to that old religion, and goes a little further back, in the sense of getting back to first principles.

I think there’s a lot of foreshadowing. I don’t want to list them all. I think it’s more fun to go find them. And I’m curious to see what people notice, and I’m also curious what hidden meanings people discover on their own that I hadn’t even contemplated. That’s the nature of symbolism. I’ve described it as like valences: Certain atoms are predisposed to link up with certain other atoms to become molecules. And that’s true of symbols, too. I couldn’t have anticipated a tenth of the compounds that these symbols might form in readers’ minds.

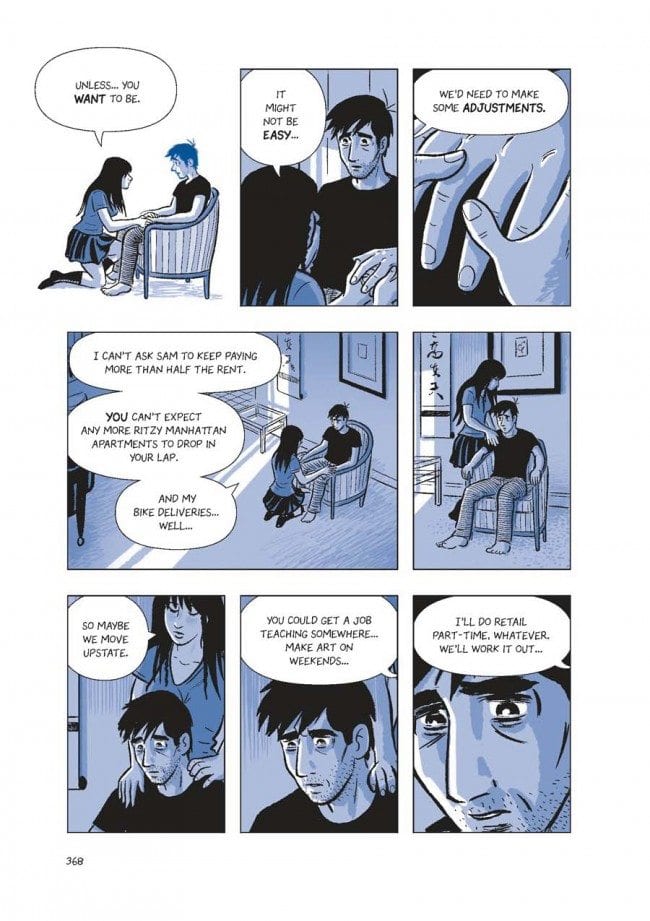

But there are a lot of little things, like Meg fastening a button on David’s shirt that she’s loaned him, from her boyfriend, and telling him, “No more talk of love, Romeo,” is an illusion to Romeo And Juliet. At that point in the book, nobody’s going to start thinking about death. But after you’ve read the book, it might have that resonance. And there are paired scenes throughout the book. I hope that’s something people will notice on later readings. Like when Meg is describing moving upstate and starting a family, that parallels Harry telling David about the life he might have. They use some of the same examples, but when Harry describes it, it sounds awful to David, and when Meg describes it, it sounds like something he might have wanted. There are a ton of themes like that that resonate with other themes.

After we’ve spent so much time watching David angst about what he’s going to create, and whether people will see it, and how they’ll take it, is part of the satisfaction of the ending just that he makes a statement that’s personal to him, and doesn’t live to see how it’s received?

He doesn’t give a shit in that moment. He honestly doesn’t even care —and yet he does. It’s a very private act, and yet a very public act. I’ve described it as my bid to have an ending that goes all the way to the ceiling and all the way to the floor. It delivers an ultimate acceptance, which we see that morning in the bed with Meg. That acceptance is still part of him, it hasn’t been forgotten. But we see him simultaneously pushing against it with all his might, and creating this massively public thing. I like the idea of the ending giving us both those messages, and this unresolved ambiguity. But not the fuzzy, wishy-washy kind of ambiguity, but this massive stalagmite and stalactite crossing each other. And rising and falling all at once, which is how a character describes David’s sculptures early on. I like the idea of an ending that seemed to rise and fall all at once.

Can’t you always say about art that it’s a private act and a public one at the same time, that there’s a perpetual tension there?

It’s not a deliberate statement about art. But I think that’s a valid way to look at it.

There’s a similar tension between the idea that he’s finally gotten his audience, and he’s given up on caring.

Just as we’re left without any judgment as to the worth of this thing he made, we’re not even sure it will last. I could imagine on the very next page, the girders start to bend, the structure is unsound, and the whole thing comes crashing down. Like Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty. Is this just a temporary moment? Yeah, people will remember it, especially because they’ll never know why any of it happened. But is it really permanent? Is it really going to last?

The material is also a couple of buildings that are either just going up or just going down. There’s a feeling that the city could bulldoze the piece. Certainly with it being a female nude, there are going to be calls that it’s inappropriate, and that the city should get rid of it.

As a matter of fact—I didn’t get around to it, but in that last conversation with Meg in bed, the flashback to that morning, one of my ideas was to have David talking about his night sculptures, how some of them were already being bulldozed over, and that it was already happening to him, just like it happened to his family. But I was pushing 500 pages at that point, and people were getting nervous.

So does the ending have any larger message about not trying to make a statement with art, about prioritizing the personal?

There’s a philosophy of art that says you should have no philosophy, and you really shouldn’t care. You shouldn’t be trying to send a message, persuade people, or do anything. That the only valid reason to create art is because you have a need to make it. And if you give a shit what anyone else thinks, you’re doomed from the start. I don’t know if that’s true or not, but it certainly describes one of David’s problems, that he cares too much what people think, and it gets him in trouble.

I have this character of the critic at one point, who steps in like a stage villain, with his fingers tented, and an arrogant smirk. But like all such characters, it doesn’t matter whether he’s a prick. He can still be right. When David overhears him talking to some friends about how some artists are always looking over their shoulders to see what other people think, David knows on some level he’s right. And it’s ironic, because that’s exactly what David is doing—he’s listening to the guy, he’s giving his opinion the time of day.

You’re always so critical of your own work, your drafting and layout skills, your ability to communicate what you intended. Even in this conversation, you’ve belittled yourself. You seem to be your own worst critic. But apart from your self-criticism, have you reached a point yet where you can stop looking over your shoulder and worrying about what other people think?

No, because I don’t have that as a personal philosophy. Because what I’m doing is part art, but it’s also part storytelling, which is a little different. Storytelling by its nature is a creature of its audience. If you honestly don’t give a shit what anyone thinks, and you’re a storyteller, you’re probably a pretty bad storyteller. [Laughter.]

I like a lot of the things I’ve done. I’m very fond of a lot of things I’ve done, this book included. This book and Understanding Comics are probably my favorite things I’ve ever done. And I might like this one a little more than Understanding. But the only reason I was able to get to this point is by working hard to understand my own shortcomings. And that can take years. It can take a long time to bring your own work into focus enough to see the parameters of its failures, and try your best to work through them.

I knew from the beginning that my figure drawing was not great, but it took a long time to understand the ways in which it wasn’t great, and to develop strategies for overcoming that. I mean, I wrote a whole fucking book, trying to teach myself to draw better figures and faces. That’s why that chapter is so long in Making Comics. I was doing my homework. And then I went out and got some actual real humans to pose for me, and that helped. Now I kind of like the figures and faces in this book. I can still open to any spread of this book and see problems. I look at this book now and know, I’m confident, that this is the best book I was capable of creating at this point in my life. And that’s not always true. Usually I can look at my books and think, “Well, if only I had more time. If I wasn’t rushed, this thing here would be better.” That wasn’t the case here. I had as much time as I needed to make it the very best book that I could. Thanks to First Second, and a very understanding editor, I took those five years and I got it as right as I could. If I was a little less critical of myself, I think at this point I would just suck more. Doesn’t that stand to reason? [Laughter.]

You’ve got to remember, I’m an engineer’s son. That’s a very big deal for me. I tried to take a much more intuitive approach to this story, and not try to be formalist and diagrammatic, and point out techniques. I wanted that stuff buried. But there’s still this analytical side. And one of the things that characterizes artists like me is that it’s all information. Any kind of feedback at all is just data. If somebody hates the thing, I’m going to see if I can figure out why and then work on that. It’s not personal, it’s just what the work does out in the world. It makes these people happy, it makes these people sad, it makes these people angry. Let’s see if we can figure out why that is.

Tasha Robinson is the Senior Editor at The Dissolve, Pitchfork Media’s dedicated film review and commentary site. She also writes about books and comics for NPR Books. She is on Twitter as, predictably enough, TashaRobinson.