[Editor's note: We asked Julia Wertz to interview her friend and colleague Sarah Glidden on the occasion of the latter's recent book, Rolling Blackouts. They caught up during a car trip a few months back]

[Editor's note: We asked Julia Wertz to interview her friend and colleague Sarah Glidden on the occasion of the latter's recent book, Rolling Blackouts. They caught up during a car trip a few months back]

JULIA WERTZ: Sarah, would you summarize the book real quick for us?

SARAH GLIDDEN: Rolling Blackouts is a book about journalism, comics journalism. The idea came when I was working on my first book. Some friends of mine were in the midst of starting a non-profit multimedia journalism collective. They did most of the reporting in Seattle for different journalism organizations—NPR, Seattle Times, stuff like that. They’d get funding mostly from grants about once a year to do a bigger international reporting projects. So, when I’d go out and visit them, they would always have these great stories about all the reporting they’ve done and all the places they’ve been. It got me really interested in finding out more about how journalism worked. It also sounded really fun. I always wished that I could go with them on one of their reporting trips. I asked them if I could go with them on their next trip and shadow them while they worked and do a book about how journalism works. About how they find their stories and their sources and how they find a translator and things like that. That’s the book.

You were following Sarah and Alex—they were the journalists. Then Dan, who is the Iraq vet, came with you guys. The Globalist was there?

They were first called the Common Language Project, but they rebranded as the Seattle Globalist.

The whole book keeps asking, “What is journalism? What is the point of it?” Do you think their intentions in going to Iraq and Syria … were they naive? Were they well informed? Or maybe too optimistic in getting a story?

I don’t think they were naive. Their idea for this reporting trip was to do some stories about displacement after the war on terror and the war in Iraq. Their audience is a younger audience, and they thought they wanted to look into young Iraqis and Iraqi refugees. What is the fallout from these wars? Who are these people who have been affected by the Iraq war? I don’t think there was anything naive about that. I think they did a good job.

Sarah said that she didn’t know what type of a journalist she was. What are the different types?

I think she meant more in the abstract sense. Like what is she trying to achieve with her work.

What’s her narrative?

Sure. What kind of journalist do you want to be? Focusing on more newsy things? Clearly, they are a freelance collective, so they aren’t the type of journalists who are backed by Frontline or the New York Times. So, what does that mean? I think that all of us, cartoonists included—what kind of cartoonist are you? What kind of work are you focusing on?

Yeah, like the different genres of it. How did you friends and family feel when you told them that you’d be taking this trip?

My mom thought it was great. I think everybody was into the idea. I have some Israeli friends who thought that going to Syria would be dangerous and a big mistake. Everyone was supportive.

As your friend, I was nervous. [Laughter.] I think it’s important to point out for the readers, that this was before the …

This was in late 2010.

Before everything went to shit.

It was a very different Syria at that time. It was even a very different northern Iraq. Now there is a lot of tension. ISIS is encroaching on that territory and the Kurdish peshmerga are on the front lines with ISIS. But when were there, we’d see these peshmerga checkpoints. And we’d see military training locations, and say, “What are the peshmerga training for? There’s nothing going on right now.” We felt the same way when we were in Syria. That was very naive. Just to assume that you’re in a place and politically no conflict seems to be going it, that means it’s going to stay that way.

How did you get interested in journalism the comics way? I think we were both kind of late to comics. How old were you when you started?

I was 26, so yeah, pretty late.

Were you interested in journalism before that? How did that even come about?

I think I moved sideways into journalism from autobiography and memoir because that’s how I started. We got to know each other because we were both doing autobio comics …

Bad autobio comics. [Laughs.]

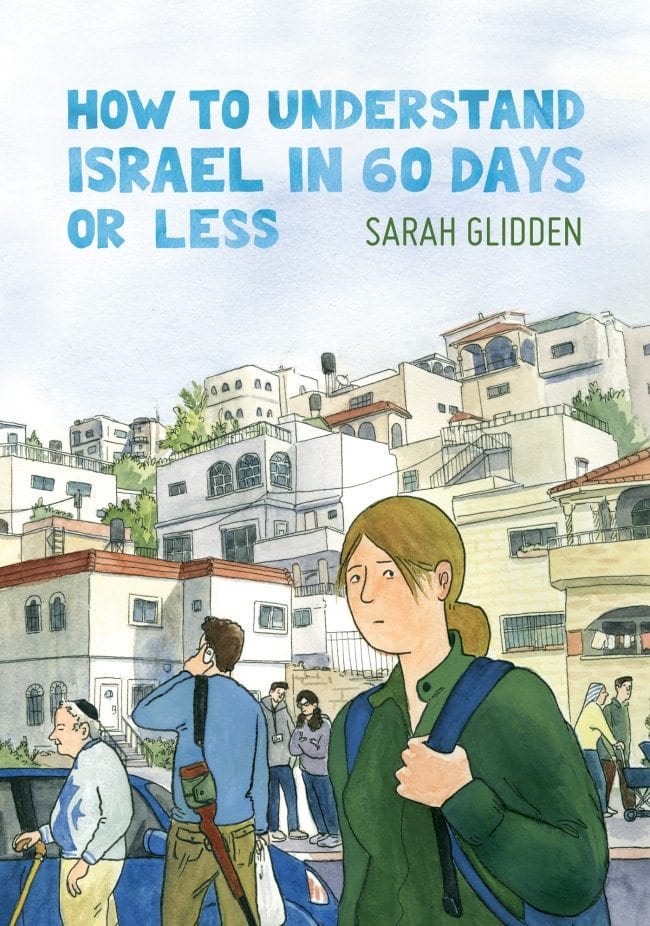

… and posting them on Flickr. I knew you through your Flickr avatar before anything else. You make autobio work about what interests you and what’s happening to you. My first book, How to Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less, was an extension of the autobio stuff I was doing. I thought I’ll go on this trip. It was a free trip, paid for in part by the state of Israel, so I thought it would be a real interesting and weird trip. Then I would just make comics as if I were doing my normal work. Comics about my experiences and what I was thinking and feeling. Lots of feelings. But that also entailed doing a lot of research into the places I was going and that’s just what I’m interested in—trying to figure out why the world is so … interesting.

You also talk about marketing stories. Her article got dropped by—who was going to do it? They said it was too dark.

Sarah had pitched a story about displaced people living in abandoned [Saddam Hussein?] barracks and prisons in northern Iraq. She pitched it to the World. I think Alex wrote the pitch, and they wrote back saying that it was too dark.

Is that a thing journalists face a lot? Having to pep up sad stories?

I don’t know. To be honest, I don’t know exactly what that email was. Sarah was paraphrasing and it would have been a creative paraphrasing. But I think that when you’re pitching a story and every part of the journalism process—the reporter and the editor—it’s the reporter’s job to try to find what they think is an interesting story, but then it’s the editor’s job … Let me put it this way: a journalist is closer to their subject and the editor is closer to their audience. Between the two of them, they are compromising on how to give the audience a story that is interesting and important.

Sure. That’s why editors always pick titles for the article.

Right. A lot of times the editor will write the headline, not the journalist, so a lot of times you end up with headlines that make journalist really upset.

You guys talk about the guy who was going to buy a heater and that brought up how journalists have the responsibility to not intervene in their subject’s life. Is that difficult? What is the downside of intervening in an interviewee’s life?

You’re talking about the scene where Sarah was interviewing a guy who was living in a displaced peoples camp and he was complaining about the cold. A friend of ours, another journalist named Kamaran who is Iraqi-Kurdish, was interpreting for us during that interview. The guy was talking about how cold it is and how it family gets so cold and all he really wants is a heater. Kamaran said he would try to get the guy some help. As American journalists, that’s kind of one of the ethical guidelines—you don’t give gifts to the people that you are interviewing because if that was something journalists did, your subjects would be influenced by the promise of gifts. You don’t pay people for interviews. That’s what that was about. But I think for Kamaran, it was like, I’m going to do whatever I can to help this guy.

Is that hard, not to help people?

Sure. Journalists have an impulse …

Especially when the intention is already there to help, to get eyes on the story.

The intention of journalism is not always going out there because you want to help that person. You’re hoping that person’s story that you’re putting out there in the world will help people understand a bigger issue. That story can stand in for something bigger than just one person, and can help them understand a phenomena like displacement or war. Sarah was always talking about making it very clear to the people she was interviewing that she doesn’t believe that this story would necessarily help them directly. That comes from an exchange. A person wants to tell their story because they want their story to be told. That’s all the journalist can offer. You can’t even promise that the story will be told because you do have to deal with the editors and you can publish something and that doesn’t mean people will read it. In the end, you have to have the faith that it’s important to put these stories out there and it’s important for people across the world to understand what people are going through somewhere.

What are the challenges between a freelance journalist doing what you guys did versus someone from the New York Times doing what you guys did?

New York Times and other papers like that used to have foreign bureaus all over the place, but those have been shutting down a lot more. It is a lot harder for someone who’s posted overseas to make the connections and understand the region a little bit better. You end up having freelance reporters going and dropping into places that are new to them. Obviously having that kind of institutional support and the money to send reporters to these places and keep them there for a long time is better. What also happens when you have someone abroad like that is that they might end up going to the same people all the time. They might end up having sources that are closer to the government and that are going to give a certain point of view that a freelance reporter, just by not having those connections, might have to talk to people who are closer to the “everyman.” The people who are actually living in these places and not in control of it. I think both are necessary, but it’s distressing how there’s less and less institutional support for international journalism now at a time we really need to understand the rest of the world a whole lot more than we actually do.

One of my favorite parts of the book is seeing behind the scenes of journalism. When Sam, the guy who was being interviewed, pretended to wake up and go about his routine. You just don’t see that. And also, I liked the part where the little Turkish kids run up and you think they’re asking you for money, but they give you guys candy. Were there any other misconceptions that you or other people had about the people there? Things that turned out different?

Sure. I think you go into a story or a place or a person with some idea of what you think you’re going to get. Finding something different makes it more interesting, but you have to have a baseline to evaluate things off of. I shouldn’t have been surprised, but I was surprised by how much anger the older Iraqi refugees had.

Directed at you guys. It was harsh at times.

It shouldn’t have been surprising, but it’s not something you get to see very much with the journalism coming out of the Middle East. You hear about Iraqis being angry, but those are militant taking up weapons against American soldiers. But these are average people. Not particularly political. A lot of anger. You would be angry if some foreign government came in and turned your world upside down. I think it was good for us. I really wanted to include that in the book because I think it’s not a side of things we usually get to see. Often, when someone’s a refugee, it’s tempting to just view them as a victim. Someone who has been wronged. But people who’ve been wronged are allowed to have feelings about it and be angry. And to ask questions back to the journalists like, “Why did your government do this?” It shouldn’t have been surprising, and it really wasn’t, but it’s something we hadn’t been able to hear before.

Yeah, most reporters don’t include that. I thought it was interesting because it made me feel like Americans are so narcissistic. Personally, I didn’t think about that aspect or that the average citizen over there being really mad about Americans coming in. But, of course, they are. Later when you guys are at [The Refugee Processing Center] when she yells at you. I feel like most journalists would cut that. But you actually see the dialogue. When you have them speaking in their native language and then you have the translation of it, how did you decide to do that visually? Their word bubble is behind the translators. How did you decide to do it that way? There are other options.

All the other options seemed to be bad. I thought of putting what the person is saying in Arabic or in Kurdish and then doing what the interpreter in the same panel, but my panels are already pretty text heavy as it is.

That would be laborious.

I stole the idea from documentaries and from radio pieces where somebody is speaking in their original language and it’s overdubbed by the translator or interpreter’s speech. It’s their world balloon and you can kind of see some of the letters of what they’re saying in their original language, then the interpreter’s balloon is on top of it to show that they are translating. There are some moments that aren’t translated because the interpreter wasn’t translating what they were saying, so I just kept everything there.

Walk me through a day of making the book.

For a long time, I was just writing it. I had to transcribe everything. So, all of the dialogue is actual dialogue. I had this digital recorder that was on almost all the time—in the interviews, but also when we were in between the interviews, walking through these towns we were in, having breakfast. And so, I had to transcribe all of that. Probably, I didn’t have to transcribe all of it, but I wanted to. I just wanted to have everything in front of me so I could see what I had to work with.

How long did it take to transcribe everything?

It was about a year of transcribing but I was working on other things. I was working on some short projects, and things like that—and traveling a lot. Writing is the thing that takes longest for me: just deciding what scenes I want to use, and how to edit down a three-hour long conversation to something that won’t last more than five or six pages of people sitting around and talking.

When you got to the drawing part—

Oh, that was the easy part. Once everything was written, then I usually work two pages at a time. I pencil and ink two pages one day, and then watercolor the two pages the next day.

What watercolors did you use?

Winsor Newton.

You only use five colors, right?

Oh, well, like five, six, seven, like…I started adding some new colors as the book went on. But yeah, I use a limited palette. I’m not doing anything colorful and exciting like Lisa [Hanawalt]. [Laughs.]

But it matches the tone. It would be weird if you had a lot of hot pink panels. [Laughs.]

That’s probably true. I studied oil painting in school, so I learned how to paint by mixing my own colors out of very few tubes. So, that’s how I approach watercolor.

It looked like you had a much more complex palette of paint. You must be good at mixing it up. What’s the hardest part about painting?

Night scenes. The darker the scene is, the more paint you use, and the longer it takes. It’s really hard to put down large areas of paint and make it look good. Watercolor is better for lighter colors and for giving more air to things. Any of those night scenes, where there are a whole bunch of layers of really dark blue—and then, if you wait too long and let and edge dry, and then you need to go back into it, it will create these colors butting up against each other, and it doesn’t look very nice. Night scenes are the hardest. They’re also cool lighting challenges. I guess that’s a fun part of doing a night scene, just having to think about, what does it look like when there’s a bunch of buildings at night, and the lights are on, and the TV’s on in one window? They were the most difficult but I also had a lot of fun.

Comics journalism is kind of new, at least to the general public. What do you think of the state of it now, and who’s doing good stuff? Or stuff you like?

I think it’s great! With places like The Nib, which are devoted exclusively to comics journalism. Other websites—or even magazines—which aren’t traditionally into comics, but adding comics journalism. I think there’s a lot of people doing a lot of really good work, like Joe Sacco, who’s been doing this for so long. He’s great. And he’s done work for Harper’s, publications that aren’t prone to using comics. But there’s a lot of great new people too. I really like Sam Wallman’s work. He’s an Australian cartoonist. A lot of the stuff on The Nib I think is really interesting.

Is it still a small field? A couple of you working, or do you think it’s a lot bigger than people assume? I assume it’s small.

It’s pretty small, but comics journalism—there’s a range of stuff. Lisa does comics journalism: her restaurant reviews and her movie reviews. She’s done things like the visit to the toy show. That’s comics journalism, also. I actually use her work when I do classes. I use her work as an example of comics journalism too, because I want people to know it’s not just stories about refugees. The things that you traditionally think about are Joe Sacco-style comics journalism.

Right. Very political.

I mean, you do comics journalism. I think that, in that way, sometimes people forget that there’s more to comics journalism than The Nib. Anyone working in nonfiction—basically, the lines can blur between memoir and journalism. I think that’s where New Journalism that started in the 1970s and ’60s comes in. I think that’ lots of things can be comics journalism. I’d be interested to see more movie reviews in comics form, or just like, “Here I am, dropping in to the swap meet for a day, in a new place. What is it like?”

You think it’s more palatable, especially for younger people, to see a comic, versus seeing a textbook or an article?

I don’t know about palatable, but I think that maybe comics can make people take a second look at something. At the moment, we’re bombarded by text and photos all the time. So, drawing and images that are hand drawn are more rare. When you see a comic, maybe you’ll take notice and want to read it, just because it’s different. What will happen when there’s as many comics journalists out there as there are prose journalists, maybe then people won’t really be into it anymore. At the moment, it’s an exciting time, because it is still fairly new. I think people can pay attention.

It’s entertaining, too. I think, for kids, it’s hard to read a textbook of information, but when they can see it, it’s much more entertaining. So, a lot of the content of the book is really difficult and dark. How does that affect your daily life while reporting on it?

While reporting on it, or while writing about it?

Just dealing with the material.

That was hard. While you’re in an interview, you have to hold it together. Especially for me, I wasn’t even interviewing, I was just there, watching. So, I need to just not be intrusive at all. And that meant keeping it together when people are talking about really sad things. But writing about it is tough, and drawing it can be really difficult. That’s when you start to really internalize a lot of the things that people were telling you. Sometimes, when you’re drawing someone making a funny face, you realize that you’re making that face. So, you’ll be drawing someone smiling like a grimace-y smile, and then you realize that you’re smiling that way. So, that works for sad moments, too. If you’re drawing someone telling a sad story, and you’re trying to— it’s a little bit “acting,” like you’re trying to put yourself in their shoes, and trying to get the facial expression right, or the emotion of the scene right. In a way, you’re inhabiting that person. That’s when it can be really tough.

It’s also something like, well, boo hoo, I felt sad when I was working on a comic about something that actually happened to someone. You feel like you’re not even allowed to have those feelings. But it is hard. For some of the people I was drawing, by the time I was drawing them, the war in Syria had broken out, and I didn’t know where everybody was. I’d kept up with a lot of the people we had met there. And, some of them are safe. Like Momo and Odessa, the Iraqi refugee couple, those younger artists, they resettled in Vancouver. I see them update their Facebook almost every day, and I know that they’re fine. But some people you’ve lost track of, or there’s just no way to know where everyone is. So, that’s tough. You’re drawing someone, and you don’t know if they’re OK.

If they’re dead or alive.

Yeah. So, it can be really hard. You feel really powerless. You wish you could just do something, and then this thing, where you’re just drawing them, is the best thing I can do. And, that feels really futile sometimes.

Speaking of helping, though. What would the average person, like me, how can we help the refugee situation?

I think just listening to refugees’ stories. And not trying to hide from the reality of the situation, especially for all refugees, not just Iraqis, and not just Syrians. There are millions of refugees from Somalia, still. It something that I think we don’t really want to look at. There’s a lot of misinformation here.

Like Trump saying the refugees coming in are causing crime.

Right.

Jesus.

He says things like, “We need to vet them properly, we don’t know who they are.” You saw me getting really upset when he said that during the debates, and then, right after that, Hillary said, “Well, we will be vetting these people.” And I’m like, “No. These people are already vetted as much as you can vet someone.” We can’t look into people’s hearts, and know what their intentions are.

That’s why it’s insane when he said, “We can’t be certain of their love for our country.”

You can’t be certain of anyone’s—

Yeah, that’s a ridiculous thing to say.

But, it’s a really stringent process that all refugees go through, especially refugees from Syria. We let in the most vulnerable people first, women and families. It’s not like we’re letting in hordes of single, young men, which are the ones that these people are the most afraid of. I think those guys deserve a chance too, but really, the reality is, only one percent of registered refugees ever get settled. It’s a very, very small number. I think that the average person can educated themselves about that stuff, and demand that their politicians do better, because we could let more people in. We have a fine history, in the U.S., of helping a lot of refugees. We let in many, many Vietnamese refugees after the Vietnam War, for just one example. We could do better with Iraqis and Syrians.

Do you think people are just afraid, because “terrorism” is such a hot word right now?

Yes. I think people are afraid because people purposely try to make them afraid. People believe when people tell them things [laughs]. I think that journalists, we need to do a better job giving people the real information.

The correct information, too. Trump has incorrect numbers.

Yes. [Laughs.] Just being curious and being informed. I understand that there are a million issues out there. There’s racism, and the treatment of Native Americans. There’s environmental destruction. When you think about all of the stuff that we need to pay attention to, I can understand people being overwhelmed. So, actually, yeah, I don’t know what people can do.

Is there a charity you would recommend, for refugees? A specific one, are all of them all right in general?

I think that everyone needs to do their own research with Charity Navigator, and things like that. I think the UNHCR does good work, but there are some who say that the UN is making a lot of mistakes with refugees. I’m not going to get into that. But, Mercy Corps is an NGO that we talked to a lot when we were over there, I think they have a pretty good record of helping refugees But I think that people can look into that on their own. Charity is always a good thing. It never hurts. But I think really listening, and not just taking the information that you get for granted is a good first step.