In the fall of 1969, critic Osabe Hideo opened an essay in the journal Bungei shunjū with the following anecdote. He thought it symbolic of the recent “gekiga boom.”

Recently, an American publisher came to talk business with Saitō Takao, known for his comic Muyōnosuke. Asked how much he could pay, the publisher said ten dollars per page. “So I said to him, You gotta be joking. Ten dollars, that’s 3600 yen. That’s a quarter of what I usually get paid. They really look down at us, thinking anything Japanese is cheap.” It seems he rejected the offer with, “I won’t work for less than forty dollars a page.”

From this, Osabe estimates that Saitō must be making something like 15,000 yen per page. If it is true, as Saitō claims, that his studio, Saitō Production, was generating 360 pages a month, this works out to about 5 million yen a month and, including other income, 80 million a year. This was not tops in the industry – Ishinomori Shōtarō, for example, was cranking out 400-450 pages a month at the same pay rate – but Saitō’s open pride in mass production was what made his operation, rather than others, newsworthy in the high growth days of the late '60s.

Osabe continues, “It doesn't all go to him, though. The studio is set up like a company.” The essay proceeds like an exposé on new business models. “Saitō meets twice a month with his three production captains and scriptwriting staff. Together they decide the plot and the scriptwriter writes the scenario. On the basis of this script, Saitō makes rough sketches in pencil. He decides the breakdown and the basic perspectives, like film boards. Following this sketch, the captain of each title draws a concrete layout, and the six chiefs and sub-chiefs, and the eleven members of the production staff, draw in the characters and background in pen.” Osabe compares Saitō’s own role to that of a film director, pointing out that like movies his comics have a full roster of credits on their title page. “So my employees aren’t like the ‘assistants’ in other studios,” Saitō explains, “They’re like the production staff for a movie.” Then the metaphors get mixed. He pays his “captains” like “section heads at a big company.” Which was it, a movie crew or a corporation? Now with thirty employees, Osabe says, Saitō hopes to expand to fifty in the near future.

About content, Osabe cares little. He makes just one observation – “Muyōnosuke reminds me of Kurosawa Akira” – but not to theorize its images of lone-wolf masculinity, or even to bring in Saitō’s love of films like Yōjimbō. The point he wishes to make instead is: Move-over-Kurosawa, because between kids comics and the new gekiga there is now a “mass manga” that has usurped the movie theatre as entertainment for all ages everywhere, from children in the country to adults in the city. What was behind this revolution was not genius, Osabe thought, but the new mode of comics production best represented by Saitō Pro. He was not the only one that regarded Saitō’s manga as not just the product of this new system, but also its expression. “An Introduction to Gekiga” offered gekiga as a new way of seeing and storytelling, but others saw in the name a new ethics of making. Asked to define gekiga, Saitō answered not with aesthetic principles, but instead, “Well it’s basically an integrated art [sōgō geijutsu]. Pure manga someone can make themselves, but not gekiga. It’s like making a movie.” At the end of the '60s, gekiga meant “business” in more ways than one.

Saitō Pro might have been news in 1969, but the fact of studio production in manga was not new. Compared to the sweatshops and Faustian contracts of American comics history, the Japanese story seems quaint. There had been multi-person studios and a division of labor in manga since at least the 1930s. For example, some of the top titles from mid-century had separate writers and draftsmen – Oda Shōsei for Kabashima Katsuichi’s The Adventures of Shōchan (1923-26), Oguma Hideo for Ōshiro Noboru’s Mars Exploration (1940), Sakai Shichima for Tezuka’s New Treasure Island (1947) – but these were exceptions and typically one-off collaborations. The top story manga authors of the war era, including Tagawa Suihō and Ōshiro, both had studio hands. Those studios, however, tended to be small, and the job of assistant was often thought of as a kind of honored apprenticeship. In most cases, the name used was “deshi,” or “disciple.” In 1952, while still in high school, Tatsumi Yoshihiro was invited to Tokyo by Ōshiro to join his “dōjō” (as if manga were a martial art) and become just that, a “deshi.” Likewise, Takita Yū referred to himself as Tagawa’s, and Kusunoki Shōhei was known as Shirato Sanpei’s one and only. Not incidentally, all of the above published at some point in Garo, which Osabe introduces in his article as a magazine cut from a different cloth than the “mass-production” norm. It was sheltering, one could argue, pre-60s conceptions of the artist and accomplished deshi at a time when the manga industry had marginalized those identities.

Before the weeklies appeared in 1959, even the most popular artists usually got by on their own. Those working for the monthlies only had to hunker down at the end of the month. Most had the same release date, leaving the week while they were being printed a heaven of free time. When the magazines increased the number of freebie furoku inserts (typically forty-eight or sixty-four page, small-format comic books) in the mid 50s, things started to get busier, but it seems at most only temporary help was hired. Just as often, artists helped one another out. Accounts of the legendary Tokiwasō are filled with such anecdotes. As for the rental kashihon market, its deadlines ranged from elastic to non-existent, at least until anthologies took off in 1956. Stories around the Gekiga Studio are less clear on how its top authors filled the various anthologies they were both editing and writing. The image is one of sleepless nights, good-enough art, and filling back pages with third-rate work from no-name acolytes.

Surprisingly, given his large and steady output, Tezuka Osamu was no exception to this loose and largely individualistic system of the 1950s. One would think the documentation of Tezuka’s working methods during this, his heyday, would be more thorough, but it’s not. From what I can gather Tezuka worked largely alone, even after he began publishing in Tokyo-based magazines in 1949. It seems he brought in extra hands when necessary, but according to scholar Takeuchi Osamu, Tezuka hired his first “formal,” full-time assistant only in 1957. More were soon added. The typical tenure was two to three years, partially because of the workload (average daily sleep was reportedly one to two hours) but also because Tezuka wanted fresh youngsters to keep him informed about what was new in the world of entertainment and fashion, Tezuka himself too busy to get out. Not that I am all that versed in the literature on Tezuka, but the only diatribe against poor work conditions that I have read was by an editor of COM in the late 60s. Likewise, there is much mention of grueling work in reminiscences of the manga industry in the '50s and '60s, but no one ever describes the situation as exploitative.

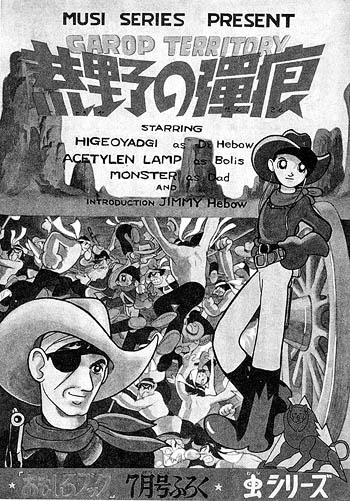

Like the history of storytelling in manga, that of studio practice also takes place in the shadow of the silver screen – first as fantasy, however. Before Tezuka had formed a proper production studio, his obsession with Hollywood and Disney had led him to project the image of one. Beginning in 1950, Tezuka would sometimes credit his work to a “MUSHI STADIO,” with the “Mushi” from his name in Japanese and the “studio” in misspelled English. This was an extension of his “star system” of recurring characters, whom Tezuka would jokingly claim as “ALL STARS OF MUSHI STADIO.” In 1951, he appended “MANUFACTURED 1951 BY MUSHI PRO” to the end of a magazine serial. Likewise in 1953, Tezuka ended his John Ford-inspired Lemon Kid with a big “THE END,” and below it “MUSHI STADIO PRESENT.” Apparently, this should not be taken as a sign that Tezuka actually had a production studio, let alone one modeled on Hollywood or Disney. It was simply the projection of a fantasy that would not be fulfilled until 1961 and the founding of Tezuka’s animation studio, Mushi Pro (initially called Tezuka Osamu Production). Tezuka Pro, a separately incorporated comics studio, was not set up until 1968.

At the end of the '50s, things began to change. The growth of the manga market meant more work, and the weeklies meant four deadlines a month rather than one. The loose and informal work arrangements that had been common began to change into more continuous, less deadline-driven work teams. In his 1998 autobiography Ishinomori Shōtarō claims that the reason he and others took on more and more work in the late '50s and '60s was not for wealth and glory, but out of a “sense of duty” to an industry that had fed their teenage dreams but was now growing too fast for itself. There were too many pages for the number of competent authors, so those with practice took on the extra load to ensure that standards of quality were maintained and new readers not disappointed. In 1969, Osabe similarly reported that “the demand for comics in our country exceeds the supply,” and moreover that “that demand is concentrated upon just some popular authors,” hence the necessity for production studios. It seems, however, that many of the first manga studios, at least those developing directly out of the magazine market of the '50s, were not formalized to satisfy the comics industry, but rather with a view to animation production. Again, the leader was Tezuka’s Mushi Pro, which was vaulted to fame with the beginning of Astro Boy in 1963. There was also Studio Zero, created in 1962 by Ishinomori, Fujiko Fujio, Akatsuka Fujio, and other former residents of Tokiwasō. It was only subsequently, mainly in the late '60s, that these same authors set up their own individual manga production studios, some of which were located on the floor below Studio Zero’s animation department, and which are sometimes referred to as “Studio Zero’s magazine production division.” All these artists had assistants previously, but direct contact with animation production seems to have been what spurred them to establish formal comics studios. On a side note, Nagashima Shinji – an assistant to Tezuka in the 50s, a friend of the Tokiwasō group, employee of Mushi Pro between 1964 and 1966, and a popular magazine and kashihon author since the mid 50s – credited himself as the first to use the name “production,” when he founded his “Musashino Manga Production” in 1957 or 1958: a failed attempt at a mixed comics and animation studio that never got beyond talk and group trips to the movies.

(continued)