"Rube Goldberg is the guy who figured out how to get from point A to point B using all the letters in the alphabet." - Art Spiegelman

"Rube Goldberg is the guy who figured out how to get from point A to point B using all the letters in the alphabet." - Art Spiegelman

Rube Goldberg started out commenting on the world and ended up changing it. As the father of American screwball comics, Goldberg helped create the iconography for a style of grotesque, compressed humor that became a mainstay of American popular culture in the first half of the twentieth century. As a cartoonist who rarely stuck to a single concept or format, Goldberg anticipated the spontaneity and artistic freedom of modern cartoonists in America. Perhaps most significantly, as the creator of those sly, beguiling invention cartoons in which the accomplishment of a simple task is made wonderfully over-complicated, Goldberg created something that took on a life of its own, and continues to have influence on the world today.

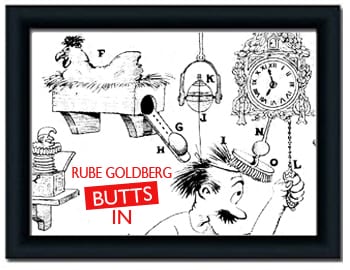

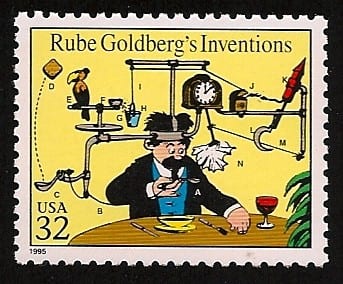

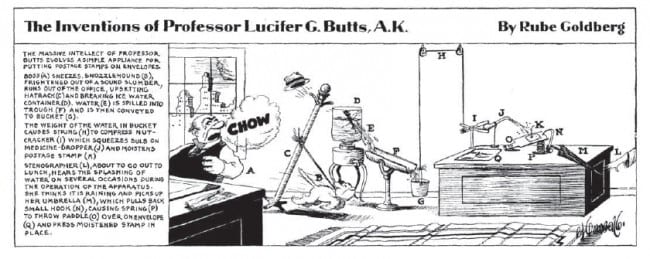

Rube butted into comics first as a sports cartoonist -- but after a few years, he started poking fun at everything around him and kept it up for close to seventy years. Of his tens of thousands of humorous cartoons, the small portion that dryly depict schematics of ridiculous cause and effect set-ups are the most famous. In fact, Goldberg's Self-Operating Napkin cartoon of 1931 was printed on a thirty-two cents United States Postage stamp in 1995, making it something of an icon.

Original art showing THE SELF-OPERATING NAPKIN by Rube Goldberg from the regular series The Inventions of Professor Lucifer G. Butts, A.K. (Courtesy of Heritage Auctions. Originally published in Collier's Weekly, September 26 1931)

In time, Goldberg's work began to influence the world it satirized. The ludicrous automatic feeding machine scene in Charlie Chaplin's 1936 film, Modern Times seems to be a Goldberg invention brought to life. Chaplin, who was friends with Goldberg, was perhaps the first in a long line of people inspired to make their own versions of these wacky inventions.

In comics, Rube Goldberg influenced scads of cartoonists, from Gene Ahern (The Squirrel Cage, Our Boarding House, Room and Board) to Milt Gross (Nize Baby, Count Screwloose, Dave's Delicatessen).

In his 1926 book How to Draw Cartoons, cartoonist Clare Briggs, (Mr. and Mrs., Danny Dreamer) wrote about Goldberg's style with an admiration that was typical among his colleagues:

"Then there is the inimitable Rube Goldberg, who has a style of drawing and a type of cartoons all his own. His originality in draftsmanship and his genius in figuring out weird mechanical devices have come in for much praise. There is probably no cartoonist who takes such liberties in drawing as Goldberg; but the effects that he obtains are remarkable. He has coined a number of the most popular slang expressions and there is no telling where his ideas will break out next. Goldberg is often a rich satirist. he can do slap-stick comedy, but he revels in the grotesque."

Briggs goes on to say that:

"When it comes to drawing, Goldberg throws away the rules. He draws the most grotesque-looking heads. One will look like a peanut. Another will have the shape of a grapefruit... The secret of his art is that he knows how to make the public laugh. No one can study his cartoons without realizing that Goldberg knows how to draw and draw well, but he has the greater ability to entertain."

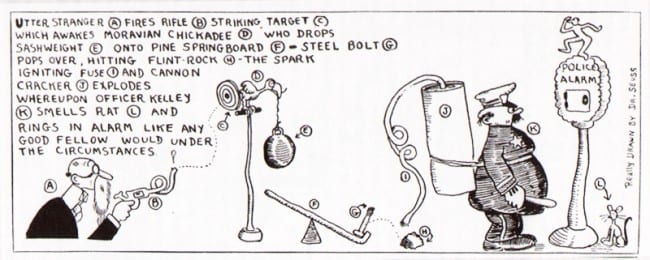

Even Dr. Seuss, whose cartoons are filled with Goldbergian contraptions, acknowledged his debt to Rube Goldberg in a 1928 Judge invention cartoon credited to "Rube Goldbrick." When one can trace a direct lineage from Rube to Dr. Seuss, whose work has in turn inspired generations of people, one begins to get a grasp of the cultural importance of Goldberg's long-neglected work.

Rube's influence is felt in engineering, as well as popular art. In the world of 2014, brainy engineering students feverishly compete to build the most complex machines they can manage to accomplish vitally important tasks like hammering a nail or zipping a zipper. They call these goofy contraptions "Rube Goldbergs."

This annual collegiate competition has been happening, off and on, since 1949! Of course, there's the Ideal board game, Mouse Trap, an unlicensed version of Rube's invention cartoons that implanted the concept of nutty cause-and-effect in generations of late twentieth century kids. Advertisers have discovered that Rube Goldberg machines can be used to quite effectively sell other machines, as in the still talked about video by Weiden+Kennedy, "The Cog," a 2003 Honda Accord TV commercial in which disassembled parts of the car are used to make a brilliant kinetic sculpture video. Goldberg sometimes invested as much as thirty to fifty hours on a single invention cartoon, a lavish amount of time for a daily newspaper cartoonist to spend on one cartoon. "The Cog" required a million dollars and 606 takes to make.

Then there's YouTube. It seems that Rube Goldberg machines and the world's clearinghouse of video is a marriage made in heaven. Currently, there are 260,000 YouTube videos featuring Rube Goldberg machines on YouTube. As Rube's granddaughter and director of Rube Goldberg, Inc., Jennifer George, observed in a January 22, 2014 CBS News Sunday Morning TV show segment devoted to the cartoonist and the tidal wave of eccentric engineering his work has inspired, "Any Rube Goldberg machine these days worth its salt goes viral." Whether it's a fine art gallery installation, or a viral video made by anyone from a car manufacturer to a rock band, the world's growing fascination with Goldberg machines shows no signs of abating.

(Mis)Understanding Rube

There are three top awards for American cartoonists. There's the Eisner Award, named after Will Eisner. There's the Harvey Award, named for Harvey Kurtzman. And there's the Reuben, named after Rube Goldberg (who also designed the award). Thankfully, the work of Eisner and Kurtzman has been well-reprinted in respectful, comprehensive formats. Their work has been analyzed and studied in numerous books and articles. The understanding and consciousness about who they were and what they did is more or less in correct alignment with reality.

Not so with with Rube Goldberg.

Considering the enduring popularity of Rube Goldberg's cartoons and concepts, it is surprising that there has never been a coherent and comprehensive presentation of his work. In his lifetime, only a very few of his comics were collected into small, humble volumes. In 1977 Hyperion Press issued the Bill Blackbeard-edited collection (now a rare volume commanding hundreds of dollars) of Goldberg's 1928 experiment in screwball continuity, Bobo Baxter. Since then, almost nothing of Goldberg's work other than the random invention cartoon has seen the light of day, until the November, 2103 publication The Art of Rube Goldberg A) Inventive B) Cartoon C) Genius, selected by Jennifer George. The lavish coffee table art book includes numerous examples of invention cartoons, but also includes - for the first time - generous amounts of work from the rest of Goldberg's career.

In writing this piece, I am making a side trip to the Department of Self-Interest Conflicts, since I edited the book with Charles Kochman, and it includes three of my essays on Goldberg, as well as my Goldberg comicography, bibliography, and timeline. However, my intention here is not to promote the book, but rather the work of Rube Goldberg. Although many think of Goldberg only as the cartoonist who made those funny invention cartoons, this is a misconception. He created much more work worthy of our attention, and mostly forgotten today. In a perfect world, Goldberg would be celebrated mainly for the richness of his comic vision and originality in all of his cartoons, not simply the inventions.

However, unless one is willing to spend hours clicking and scrolling through microfilm archives, there is little chance of truly understanding the great cartoonist hidden behind the massive -- and ever-growing -- pile of goofy inventions assembled by subsequent artists, art directors, rock musicians, and fun-seeking people in his name.

The current dusty, dim current understanding of Rube Goldberg and his work is evident in the comics history books and websites that mention him. Sadly, many of these are riddled with errors. Peter Marzio's 1973 biography, Rube Goldberg: His Life and Work contains a error-filled list of his cartoon series that has led subsequent scholars into fields of confusion.1 Marzio's book also asserts that the first full-fledged Goldberg invention cartoon was published November 10, 1914, an incorrect statement that has been repeated in numerous articles, books, and websites for the last 40 years. In actuality, it appears that Goldberg published about a dozen such cartoons prior to this date, going back to July 17, 1912.

The errors about Goldberg's work have, on occasion, been off not just by a couple of years, but entire decades. For instance, Brian Walker's comprehensive and authoritative survey of the history of the American newspaper comic strip The Comics: The Complete Collection (Abrams ComicArts 2011), reprints a Goldberg invention cartoon from 1930 with the dating "c.1910s." It's also identified as a "daily panel," when it actually was from a biweekly series that appeared in a nationally distributed magazine, Collier's Weekly.

In all fairness to hard-working cultural historians, getting one's arms around the scope and particulars of Rube Goldberg's career is no easy task. Goldberg, that cartoonist with the mind of an engineer, was more interested in the next idea than he was in exploring every nook and cranny of a single concept. Thus, for most of of his career as a newspaper humor comic strip creator from 1909 to about 1938, Goldberg made a new and different comic strip every day. This is how newspaper comics started out, with great variety and many series that only lasted for a few weeks -- but Goldberg kept it up for years after it was fashionable. For example, his late 1930s Sunday comic, Side Show, offered a comic supplement within a comic supplement, with a dozen or so different little strips and panels crammed onto the page.

Five Days of Rube Goldberg in 1917

The variety and rich comic invention of Rube Goldberg's comics can be seen more clearly when the work is studied in the context of its original publication sequence, as in the following strips from April 16 to April 20, 1917.

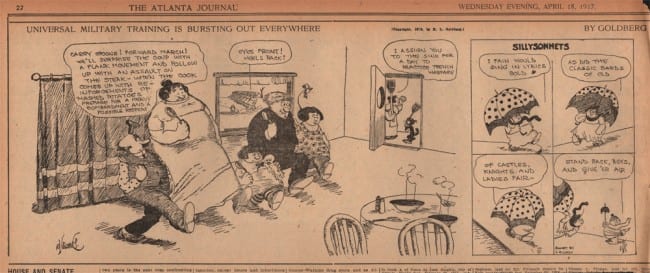

On Monday April 16, 1917 the Rube Goldberg newspaper cartoon presented an 18-part invention for curing "hiccoughs" that includes a cat, a monkey, a "laughing-sparrow," a bowling ball, and a load of bricks. Note that there's a second item, a four panel comic strip from his Silly Sonnets series.

The following day, Rube penned a new episode in his Sweep Out the Padded Cell series, which sported a different first name in the title, each time. The Tuesday, April 17, 1917 entry offers a story told in six panels about American commercial sports that is as true today as it was 97 years ago. The side comic makes a reference to World War I.

The next day, Rube's top third of a newspaper page (and, by the way, these cartoons were quite large, measuring sixteen inches across) presented a large panel finding a laugh in the grim subject of the war. In the background, a black cat stands up in what may be a nod to George Herriman. The Silly Sonnets repeats the joke of Monday, with a polka dot umbrella.

Thursday offered yet another of Rube's continuing, sporadic series: It's All Wrong, another title that featured a different name in each title. This one merges the war of nations with the battle of the sexes to get a good laugh. Note the side comic presents another of his series, I Never Thought of That.

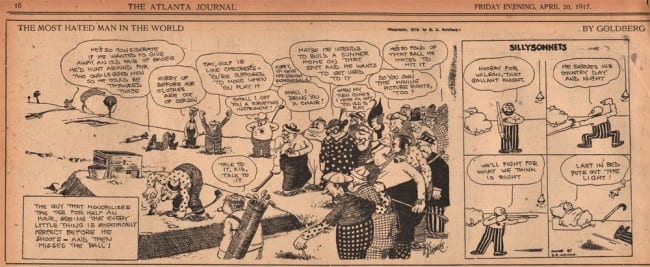

The Goldberg for Friday of the same week switched back to a full panel presentation, jammed with comic figures and commenting on golf -- a sport Rube loved and also found extremely funny. The side comic is back to Silly Sonnets, and offers a comment on President Woodrow Wilson and WWI.

The range of formats and varying subject matter in these five consecutive cartoons alone speaks to an endlessly creative mind. In effect, Rube was a one-man Saturday Night Live show, brilliantly inventing a mix of satirical and topical comedy at a furious pace from 1909 to about 1938, with only a few short side trips to relatively consistent continuity strips.2

Given Rube's tireless drive to create something new and different every day, cataloging his newspaper humor comics is exponentially more difficult than documenting the publication of most other regular strips. A strip like Blondie, can be cited very concisely: "September 8, 1930 to present." In contrast, a proper accounting of Rube's work requires a day-by-day list and description of his comics, a task so effort-laden that it is hardly surprising that it remains undone.

Meet Professor Lucifer Gorganzola Butts, A.K.

The chaotic complexity of Rube's rich oeuvre is one reason why the general understanding of the work of Rube Goldberg, an important twentieth century artist who was once read by millions, remains mostly inaccessible and misunderstood. There's simply no easy framework for generalizing about it.

Contemporary cartoonist and Disney storyboard artist Stephen DeStefano (Lucky In Love) offers another insight into why Goldberg's work is not better understood: "I think the problem with Goldberg is he didn't have a character mainly associated with him, and then his work became associated with mechanisms, rather than personalities. His drawing is exceptional, really."

While Goldberg did have a few continuing characters, such as Boob McNutt, Mike and Ike (They Look Alike), and Bertha, the Siberian Cheesehound, his comic strip characters existed mainly as vehicles for gags and comic situations. They are fairly one-dimensional. Rube was an idea man, not a creator of rich characters. Instead of a few characters deeply explored, the comics of Rube Goldberg present a vast, winding parade of human characters. This aspect of the work is both an artistic strength and a commercial weakness in Goldberg's legacy. DeStefano is right in observing that there's no anchor of character interest in Goldberg's work.

Paradoxically, the Rube Goldberg character who has had the greatest appeal, Professor Butts, was never seen in the comic strip named after him. In a post-modern twist worthy of Samuel Beckett, Goldberg built an entire comic strip, The Inventions of Professor Lucifer G. Butts, A.K. (1929-1931), around a character who never once made an appearance in it. This mysterious aspect of the character only seems to add to his presence.

Rube Goldberg created the character of Professor Lucifer G. Butts, A.K. -- his quintessential screwball inventor -- in 1928, although he had played with the name and concept of a mad scientist for years. Goldberg said that Professor Butts was based on a couple of college professors he studied with while earning his degree from the College of Mining and Engineering at the University of California from 1901-1904. In particular, he recalled Freddy Slate, whom he described in an unpublished memoir as "a spare little man with a red beard, a high-pitched voice and an urgent manner of sputtering his scientific declarations."

Even though he modeled the character of Professor Butts on his college professor, the character also functioned as a sort of alter ego of Rube Goldberg. The Professor's first name, "Lucifer," is similar to Rube Goldberg's middle name: "Lucius." Goldberg recalled the character in an unpublished memoir, written later in his life:

"In my cartoons Professor Lucifer Gorgonzola Butts invented elaborate machines to accomplish such Herculean tasks as shining shoes, opening screen doors, keeping moths out of clothes closets, retrieving soap in the bathtub and other innocuous problems. Only, instead of using the scientific elements of the laboratory, I added acrobatic monkeys, dancing mice, chattering false teeth, electric eels, whirling dervishes and other incongruous elements…"

(from an unpublished memoir by Rube Goldberg)

Professor Butts made his first appearance in an illustrated short story by Rube Goldberg, "It's the Little Things That Matter," that appeared in the November 3, 1928 issue of Collier's Weekly.3 The story includes a rare pen-and-ink portrait of Professor Butts, who looks like a dead ringer for his old college Professor, Freddy Slate.

In this typically screwball piece, Goldberg poses as "Strathmore" (a brand of the thick artist's paper that cartoonists often used). He realizes that there is a fundamental problem with the daily technological advances of humanity: "While all the big inventions were giving the astonished world fresher and louder gasps of incredulity, I could see around me many things that by their glaring deficiencies were crying out for urgent reform."

Strathmore laments the lack of inventions to help with the little problems of every day life, like gravy stains on vests and "grapefruit that, with the touch of a spoon developed into the morning shower bath." Strathmore recalls his old college chum, Butts, and realizes he might be the answer.

"No doubt you have heard of Professor Butts. But, to refresh your memory, I will recall the fact that his outstanding achievement was the invention of the park bench. He made it possible for the great mass of the retired population to sit down and give the Board of Public Works a chance to fix the streets. He also invented the Christmas card and thereby built up large practices for physicians who did nothing but treat letter carriers for lumbago." (It’s The Little Things That Matter by Rube Goldberg, Collier’s Weekly, November 3, 1928)

The Professor is a genius at inventing trivial, over-complex inventions, the very same ones Rube himself had been creating in the funny pages for about 15 years.

About a year after the Collier's article introducing Professor Butts appeared, Goldberg began a new cartoon series called The Inventions of Professor Lucifer G. Butts, A.K. Primarily a newspaper cartoonist, Rube created this new series exclusively for the nationally distributed magazine, Collier's Weekly. The comic ran roughly every other week from January 26, 1929 to December 26, 1931. Each bi-weekly episode appeared as an oblong rectangle occupying roughly the top or bottom third of a page.

For the first time, and to great effect, Goldberg added the element of a continuing character to his invention cartoon formula. In the text explanations of the diagrammatic cartoons, a few sharply satirical details about Professor Butts and his latest discovery were always included. For example, "Professor Butts gets his whiskers caught in a laundry wringer and as he comes out the other end he thinks of an idea for a simple parachute." This was the extent of the characterization, but it was enough. Instead of one-shot satires, the invention cartoons became components in the life of a nutty professor that one could imagine buttered his toast with tennis rackets and opened his garage door with a 28-piece orchestra and a large block of melting ice.

The new bi-weekly format allowed Rube extra time to polish his time-consuming invention cartoons. With this upscale format, and the prestige of a national magazine account, Rube became more inspired than ever. His rendering style became precise and sharply detailed. He painstakingly detailed decorative complex patterns in 3D perspective, anticipating (as did several cartoonist of the day) the Op-Art movement.

Rube added into each Professor Butts episode an astonishing number of objects and jokes, creating mature works of comedy. The result was a magnificent re-tooling of his standard invention cartoon, now 15 years old, into iconic perfection, escalating it from a parody of crackpot gadgets to a dense symphony of bio-mechanical beauty that transcended any trivial purpose and became a thing of wonder in itself.

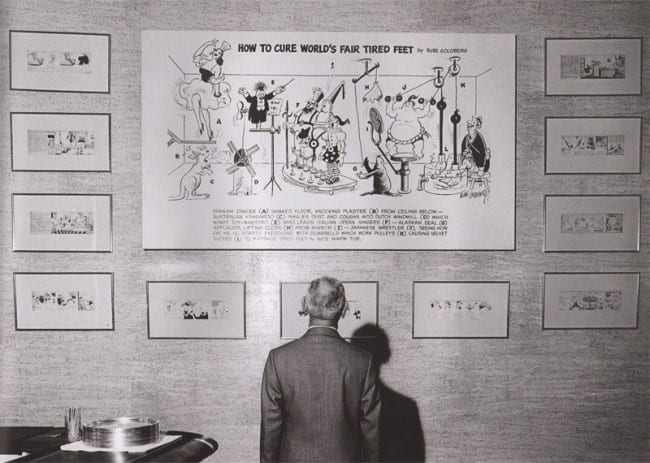

The Collier's Professor Butts cartoons, each of which took Rube thirty to fifty hours of work, represent the creative peak of Rube Goldberg's career. These cartoons are the crème de la crème of his cartoons, and have become his most popular work, by far. "The Self-Operating Napkin" (see above) cartoon image chosen for the 1995 United States commemorative Rube Goldberg stamp comes from one of the Collier's Professor Butts cartoons.

In his invention cartoons, Goldberg worked hard to find the secret and surprising ways that objects and living creatures fit together. In an October 11, 1930 Princetonian interview, he spoke candidly about his invention cartoons: “The things may look impossibly foolish, but at the same time they are quite logical. For instance when I have a goat crying in one of my cartoons I have to give a satisfactory reason for having him cry. So I have someone take a tin can away from him.” Many of Goldberg’s inventions operate as much on emotional reactions as purely mechanical processes. Steaks inch toward baked potatoes, dogs wag their tails at the sight of a revealed fire hydrant, and mosquitoes buzz loudly at the sight of a bald head.

As a humorist, Rube Goldberg had a dry-as-dust wit. He expressed that side of himself in his Professor Butts series by making his drawings of exotic parrots, midgets, Eskimos, woodpeckers, and Scottish bagpipe players as matter-of-fact as his drawings of ordinary pipes, wrenches, candles, and boots. Much like his friend and colleague, Ernie Bushmiller, Goldberg developed the ability to portray the definitive Platonic-ideal cartoon versions of objects and types of people. A strip like the “handy self-working sunshade,” with its stark beach setting, hare and tortoise racing rivals, sinister jack-in-the-box, ominous cupboard, and conceited peacock perched on a supine sunbather’s chest was as dreamlike as any painting by Magritte or Dali -- sheer visual poetry, and surrealism at its finest.

While the image of Professor Butts could not be found in any of the 1929-31 cartoons named after him, his voice could be heard on the radio. The screwball inventor, portrayed by an actor, could be heard "egsplening" his inventions in pidgin English on the Sunday evening Collier's Hour radio variety show during the 1929-30 season. Goldberg even appeared on a the show a couple of times, as himself. Oddly, the many ads in the pages of Collier's that promoted Professor Butts' appearances on the radio show featured drab, overly realistic portraits of the character drawn by someone other than the cartoonist who created the character!

There are only about 70 episodes of The Inventions of Professor Lucifer G. Butts, A.K., and they rank among the most celebrated Goldberg works. Numerous books, articles, and websites incorrectly ascribe all of Rube's cartoon inventions to the inventor. In actuality, Goldberg created the character years after he began drawing his invention cartoons and then only used the character sporadically after 1931. Most notably, Professor Butts appeared for a few weeks in 1934 in Bill, the topper strip to Goldberg's Boob McNutt.

In later years, Goldberg recreated Professor Butts as a less crazed, more genial character. Goldberg drew him as a short, rotund, bald man peering out at the world through thick-rimmed round glasses. Rube's granddaughter, Jennifer George, once imagined that the actor Wallace Shawn would be a suitable choice to play this version of the character. There were no further comic strips or short stories published featuring this character, but Goldberg used the indefatigable inventor in numerous sketches and cards distributed to friends, colleagues, and fans.

An Inventive Comics Master

Today, Rube Goldberg is mainly known for his invention cartoons. In fact, many people assume he was a real inventor, tinkering in a workshop stuffed with cogs, pulleys, and all manner of items. In reality, this feverish inventing took place solely on paper. This was made abundantly clear in a 1959 TV interview with Rube Goldberg and his wife, Irma, conducted with Edward R. Murrow:

Murrow: Mrs. Goldberg, with Rube spending so many years telling millions of us how to get things done, he must be a perfect handyman around the house.

Irma: Well, we've been married 42 years, Mr. Murrow, and he has never done anything useful as yet, like even fixing a bell, or an electric switch.

One could argue that Goldberg's best inventing occurred in his lesser-known, and largely uncatalogued three decades of daily newspaper humor strips, only a small fraction of which featured his bizarre machines. The recent book, The Art of Rube Goldberg A) Inventive B) Cartoon C) Genius, selected and overseen by his granddaughter, Jennifer George, takes a satisfying and meaningful step towards a reassessment of the seminal cartoonist and his valuable body of work, but there's literally a library's worth of great Goldberg comics still waiting to be rediscovered.

As the appreciation and scholarship of America's comics from the first decades of the twentieth century deepens, the day may come when Rube Goldberg's non-invention cartoons are as prized by cartoon aficionados as his invention cartoons are among the general populace. The variety and mastery present in his daily newspaper comics from 1912-1918, in particular, would be a revelation to many.

In a time where entire decades of classic American newspaper strips are being impeccably reprinted, it seems within the realm of possibility that complete years of Goldberg's ever-changing daily humor strips, presented in the order of their original publication, could become available to read. It would be the first time in history that the work of this seminal cartoonist would be available in an archival presentation, instead of a selected assortment. Such a presentation, one suspects, would reveal that there is even more to celebrate and appreciate about Rube Goldberg than we already do.

Notes:

1. The Art of Rube Goldberg A) Inventive B) Cartoon C) Genius selected by Jennifer George (Abrams ComicArts, 2013) contains in its back pages my list of Rube Goldberg's comic strip series. By no means definitive, it is more comprehensive and accurate than any previous published such list.

2. For more on Rube Goldberg's Collier's comics, as well as information about Boob McNutt, and his continuity comics, see my essay "Restless Storyteller: Rube Goldberg's Comic Strips of the 1920s and 1930s" in The Art of Rube Goldberg A) Inventive B) Cartoon C) Genius.

3. "It's the Little Things That Matter," the Rube Goldberg short story in which Professor Butts first appeared, can be read here (page 1) and here (page 2).