Rosalind "Roz" Chast was the first truly subversive New Yorker cartoonist. Her 1978 arrival during William Shawn's editorship gave the magazine a stealthy punk sensibility. Younger, femaler, and a less orthodox draftsperson than her colleagues, Chast drew with a "ratty" cartoon style akin to Lynda Barry, Matt Groening, Gary Panter and other mainstays of the alternative press. Her first cartoon for the magazine, "Little Things," was a miniature piece of surrealism championing the "chent," "spak," "kellat," and other homely objects of everyday life.

Rosalind "Roz" Chast was the first truly subversive New Yorker cartoonist. Her 1978 arrival during William Shawn's editorship gave the magazine a stealthy punk sensibility. Younger, femaler, and a less orthodox draftsperson than her colleagues, Chast drew with a "ratty" cartoon style akin to Lynda Barry, Matt Groening, Gary Panter and other mainstays of the alternative press. Her first cartoon for the magazine, "Little Things," was a miniature piece of surrealism championing the "chent," "spak," "kellat," and other homely objects of everyday life.

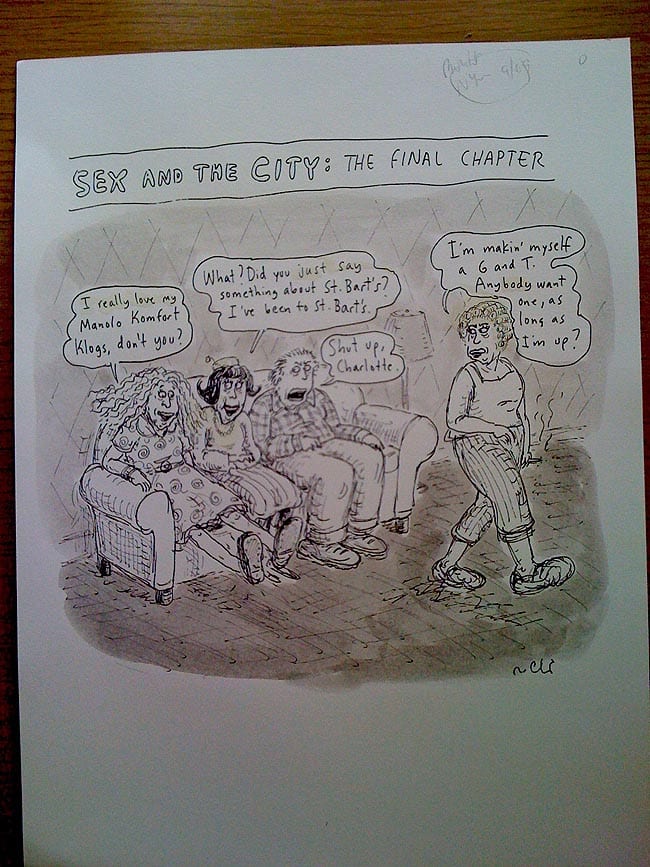

Chast went on to become The New Yorker's most versatile artist – as well as one of its finest writers. Her single- and multiple-panel cartoons, along with her lists, typologies, and archaeologies, combined urban and suburban sensibilities, with one point of view subtly undermining the other. Her viewpoint reflected both the elderly Jews she grew up among in Brooklyn, as well as the upwardly mobile liberal cosmopolitans who, like Chast, fled to the burbs (Ridgefield, Connecticut, in her case) to nest with their offspring. It didn't take Chast long to channel Everymother on the page, as her 1997 collection Childproof: Cartoons About Parents and Children will attest. But it's her hefty 2006 omnibus, Theories of Everything, which embodies the Chast sensibility in all its trivial magnificence.

We spoke mostly in Chast's studio, on the second floor of the comfortable home she shares with her husband, humor writer Bill Franzen. A carpenter was repairing a leaky bathroom ceiling down the hall, and Chast was preparing to depart that evening for a pair of West Coast lectures. A TV was on in the kitchen, which may be how the mumbling birds in the adjacent room learned to speak. The kusudama origami and pysanki painted eggs on display reminded me how much Chast's own cartoons resemble hand-crafted folk art that works both as decoration, sociology, and, of course, old-fashioned yucks.

RICHARD GEHR: Were you one of those kids who drew constantly?

ROZ CHAST: Oh yeah! That’s how my parents kept me quiet and occupied. They were older parents who were in their forties when they had me. I’m an only child, and most of their friends didn’t have children, so if they were forced to drag me somewhere it was like, “Here’s some paper and crayons. Now shut up.” And it was great!

GEHR: What did your parents do for a living?

CHAST: My dad, George, was a French and Spanish teacher at Lafayette High School. My mother, Elizabeth, was an assistant principal at different public grade schools in Brooklyn.

GEHR: Did you grow up in an academic environment – or just a school environment?

CHAST: School! School, school, school. I’ll give you an example of how "school" it was: My parents liked to give me tests when I was in grade school. They thought it was fun. So I would make up math tests for my fellow students on a little Rexograph copying machine we had at home that used was purple ink. I would make up math tests and give them out to kids in class for fun. They must have thought I was a fucking wacko. My father would also give me French tests, because he thought I should learn French. Sometimes my friend Gail would say “I don’t like it! It’s too educational” about stuff I wanted us to do. But everything in my life was educational. Education was a very big thing.

GEHR: What was high school like for you?

CHAST: I went to Midwood High School in Brooklyn, which I guess was a great school. I learned a lot of stuff and it was very "educational." But I didn’t like it. I wanted to draw. I wanted people to stop asking me questions about some tax law of 1812. I didn't care. But I was a good girl and I studied.

GEHR: Were you part of the art crowd?

CHAST: No. Just shy, hostile, and paranoid

GEHR: When did you start getting recognition for your art? Did you win any awards?

CHAST: The Kiwanis Club had a poster contest when I was in high school. The theme was "honor America." I entered it as a joke and won. I went to the award ceremony with my friend Claire, who was a total out-there hippie. We ate at some mafia Italian restaurant. My poster was just a bunch of people standing on a street with "honor America" written above them. I don't think very many people entered.

GEHR: After high school you went to Kirkland, an all-girls college.

CHAST: An all-girls school across the road from an all-boys college – Hamilton. I had a boyfriend, which was a very good thing because otherwise I probably would have left after one year instead of two. But that’s what happens. Kirkland had a great art department with all-new facilities that were underutilized because it wasn’t really an art school. You could go there almost any time of day or night and find an open darkroom. I learned a lot of stuff. I did lithography, silk-screening, etching. A teacher and I figured out how to photo-silkscreen together, but we didn’t have the right tools so we did these makeshift things. I learned how to develop film and print. It was fun.

GEHR: It almost sounds like a trade school.

CHAST: And I used it as a trade school. As I said, I probably would have left after a year because I really only wanted to take art classes. I was only sixteen when I left for college and I just did not have the strength of character to stand up to my parents and say, “I don’t want to take any more academic classes. I just want to go to art school.”

GEHR: Did you graduate from high school early?

CHAST: No. I was born at the end of the year [November 26, 1954, for the record]. In New York they had a thing called the SP program where you could either take an enriched junior high school program for three years or you could do the three years of junior high – seventh, eighth, and ninth grades – in two years. I don’t know why my parents opted to have me do it in two years, since I was so young anyway. I think it was because in their day it was considered sort of a plus to go through school as fast as you could. And maybe they just really wanted me out of the house. It’s possible. They were a lot older and might have had it with having a kid around. So I was sixteen when I went off to Kirkland. Not great. I was not a mature sixteen-year-old. It wasn’t ideal but it worked out all right. I transferred to RISD [Rhode Island School of Design] after two years.

GEHR: Did you flourish at RISD?

CHAST: No. RISD was really very hard.

GEHR: Did you find the competition intimidating?

CHAST: Yes. It was the first time I'd ever been with that many other really good artists. I didn’t feel like I was in the middle of the pack; I felt like I was at the bottom. Everybody there was good, and some people were extraordinary. And some people were extraordinary and knew it. They had confidence and the ability to talk about their work. They were eighteen or nineteen, but they already knew who they were and how they wanted to dress. I didn’t even know how to pick out my own clothes. I didn’t know anything and there were people there who seemed to know everything. And, yeah, maybe they were just as lost as I was, but I don’t think so.

GEHR: Who were some of the extraordinary ones?

CHAST: I don’t remember.

GEHR: I'd throw out some names, but David Byrne's the only person I can think of right now.

CHAST: I overlapped one year with David Byrne. The Talking Heads were called the Artistics then. They played at one of the first RISD dances I went to and they were extraordinary. They played "Psycho Killer" and I was blown away. But it was very hard. There was a vicious cycle where I didn’t know how to get a teacher’s attention, so I would get depressed, and it would get worse, and so on. Another big problem, more than I recognized at the time, was that I don’t think cartooning was particularly appreciated when I was there.

GEHR: Not even in a commercial, illustrational way?

CHAST: No. One of the more terrible things about cartooning is that you’re trying to make people laugh, and that was very bad in art school during the mid-seventies. This was the height of Donald Judd's minimalism, or Vito Acconci's and Chris Burden's performance art. The quintessential work of that time would be a video monitor with static on it being watched by another video monitor, which would then get static. Doing stories or anything “jokey” made me feel like I was speaking an entirely different language.

GEHR: Did you keep trying to draw humorous stories?

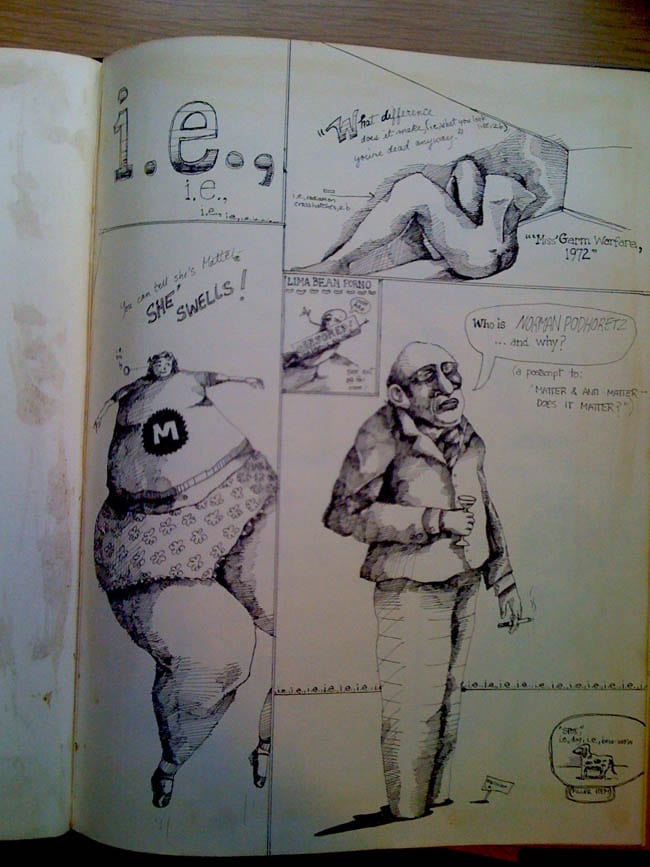

CHAST: That’s what I started out doing. This is going to sound horribly bitter, but some boys actually started a comics magazine at RISD called Fred, and when I submitted some stuff, they rejected me. I cried and cried. I cried like a little girl [laughs] – which I was! I felt very bad. I was heartbroken. But it makes me very happy now to think that while they may have become good artists, not one of those boys went on to become a cartoonist.

GEHR: What did you end up working on there?

CHAST: I started out in graphic design but I wasn't good at it. You had to be very neat, which I was not. My teacher was Malcolm Grear, a famous graphic designer who designed the Amtrak logo, and the idea was to strip everything down to the minimum. That didn’t sound like fun to me. I like things to be more interesting to look at, and I didn’t really care about that. So I switched to illustration. That was kind of all right, and I met some people in the department whom I’m still friends with. Then I switched to painting because I was living with painters and really wanted to be a painter. But I sort of sucked at painting. Deep down, I think I still wanted to be a cartoonist. By my senior year I kind of went back to drawing cartoons, but only for myself. I didn’t show them to anybody. Oh! I did show them to one teacher, who said, “Are you really as bored and angry as all that?” I didn't know what to reply.

GEHR: Did you return to New York after RISD?

CHAST: My parents lived in Brooklyn, it’s where I grew up, and where else was I going to go? I always loved New York and felt like it was my home.

GEHR: As well as being the art industry's company town.

CHAST: As Sam Gross would say, “It’s where the work is!” I remember what he said about San Francisco, too: “San Francisco is nice, but there’s one job!” So after graduating in June of ’77, I moved back to New York and started taking a portfolio around. I got a few illustration jobs. I didn't think I was going to get work as a cartoonist, but I was doing cartoons all along because there was really nothing else to do. You know how it is? Sometimes you feel like, “What else am I going to do?” I got a little bit of illustration work. I cooked up these pastiche styles of whatever. And then one day I thought, “I’m going to try to do the cartoon thing.”

I actually had one of those weird moments – this is going to sound like total bullshit, but it’s true – when I was coming back on the train and opposite me was this issue of Christopher Street magazine. I thought: There’s nobody on the train, I might as well pick it up and see what it is. But what if people think I’m gay? Nah. There’s nobody on the train, I just spent four years at art school, so who cares? More than half of my friends are gay, yet I didn’t necessarily want anyone to see me picking up this magazine. What if it’s porn? What if it’s weird and I’m going to be all weirded out? My curiosity finally got the better of me. I picked it up and started looking through it – and it has cartoons! And it’s not porn at all. It’s got short stories and articles and things like that. And cartoons! It looked like three different people were doing the cartoons. So I gave them a call and it turned out that the three people were all one person drawing under three different names.

GEHR: Who was that?

CHAST: His name is Rick Fiala. [Fiala also drew under the names "Lublin" and "Bertram Dusk."] I don’t know what happened to him. But I wound up selling cartoons to Christopher Street for ten bucks, which was crap pay even in ’77. Then I sold a few oddball mini-panel things to the Village Voice for the centerfold, which was edited by Guy Trebay.

GEHR: When did you first approach The New Yorker?

CHAST: In April of ’78 I was still living at home with my parents, which was not good. I don't think they wanted me there any more than I wanted to be there, but I didn’t know what else to do. I decided to call up The New Yorker even though I didn't think my stuff was right for them. I found out that drop-off day was Wednesday. I didn’t know how to do it, but I had one of those brown envelopes with the rubber band. I left like sixty drawings in this thing. When I went back the next week to pick them up, there was a note inside that said, “Please see me. – Lee.” At first I couldn't read it because it had this very loopy handwriting. There was a little anteroom and you had to be buzzed in. A very intimidating woman with red hair named Natasha used to sit there like she was guarding the gates. She read the note and said, “You can go in and see him.” It was a really scary feeling, like I wish I were not here. I still didn’t think I was going to sell a cartoon. I thought Lee [Lorenz] was going to give me some bullshit talk like, "This is very interesting work, little lady.” But they ended up buying a drawing. I was pretty shocked, but he said to come back every week with stuff.

GEHR: That was the cartoon with the imaginary objects, right? I bet they paid you more than ten dollars for it.

CHAST: Two hundred fifty bucks. Real money; grown-up money. That also happened to be the rent for my first apartment: 250 bucks.

GEHR: Did The New Yorker open doors at other outlets?

CHAST: Not really. I sold several cartoons to National Lampoon, where Peter Kleinman was art director. He knew Playboy's cartoon editor, Michelle Urry. I went to see her, and I remember thinking, I don’t know. Me and Playboy is an even weirder combo than me and The New Yorker. Michelle liked my stuff, though, and said, “Maybe you can try doing these with more of a Playboy kind of feeling.” I tried, but they came out like Playboy parody cartoons. Like, Hey! Look at my bosoms! – or, Now you’re staring at my bosoms!

GEHR: Whom else did you sell to?

CHAST: I did illustrations for Ms. magazine. As people got to know my cartoons, they knew they weren't going to get straight illustrations; they were going to get something sort of funny. I did a lot of illustrations during those years. Sometimes people would ask, “Could you make your characters look a little more contemporary?” But to me, this is contemporary. This is it, even when I give characters contemporary haircuts.

GEHR: There have always been very few women cartoonists at The New Yorker. Was your gender ever a problem?

CHAST: To some extent, yeah. I've been very fortunate to have had editors who, even if they were guys, didn’t always go for jackass-type humor. But when I first walked into that room, it was all men. And it wasn’t just that it was guys, it was that they were all older. Being female at The New Yorker was just one of many things. I also had a different sensibility, I was a lot younger, and I probably didn't want to be there. I wanted to be there, but for me it was just very…fraught. I was shy. I didn’t know how to talk to anybody.

GEHR: What was the editing process like? Did you get many notes from Lee Lorenz?

CHAST: Not many. Lee's wonderful. Every once in a while he would say something. It was a very strange process.

GEHR: What made the submission process so strange?

CHAST: You went in to see Lee in person, and everybody came. There were the Tuesday people [who were on contract] and the Wednesday people. I was a Wednesday person. You went in with your batch of maybe ten or twelve cartoons – it varied from person to person – and these were rough sketches. There was a little waiting room outside Lee’s office where you’d sit around with the other cartoonists. Lee would see you in the order in which you arrived. So you’d come in and they’d say, “There are two people in front of you – Bernie [Schoenbaum] and Sam [Gross] are going in, and then it will be your turn.” You would hand over your batch to Lee and he would flip through it right in front of you. Horrible! And you’d wonder, is he smiling? Does he find that funny? Do all these cartoons suck? Why isn't he laughing? They suck. I know they suck. Worst batch ever! And I still feel that way. At some point they’re just going to say, “You know what? You’re horrible. You’re not funny anymore. Just go! This was a big mistake. Out!” Finally, if they'd bought anything during their previous art meeting, he would pull it out from this little folder and hand it to me. He usually wouldn’t say anything about it.

I remember when I sold this cartoon of a mailbox in the middle of a Midwestern landscape. The punch line was something like, 1,297,000 West 79th Street. But I never had a mailbox because I grew up in an apartment house, so I can’t draw one. Lee said, “What’s that?” I said, “That’s the handle, to flop open the door.” He said, “No” and drew the flag on the rough – I still have it – and said, “That’s what you put up when you have mail in your mailbox.” But I still got it wrong because in the finished version the flag is very tiny, as if it’s glued to the side of the box. Another time I had a guy holding a cane and he said, “It looks like he's holding a bunch of spaghetti.” No, I would not say my drafting skills are in the top ten percent of all cartoonists. But it wasn’t about drawing a horse correctly, because that’s not what cartoons are about.

GEHR: You've probably dealt with heavier-handed editors.

CHAST: Some like to really get in there and muck around.

GEHR: Have you ever had to fight to keep something in a cartoon?

CHAST: I have more issues about the size of my cartoons. The New Yorker currently only prints cartoons in two columns, but they used to occasionally go into the third column. So I've tried to fight the battle of having cartoons sized correctly rather than making them snap to a grid. It's not a battle I'm going to win, but I'm fighting it.

GEHR: Do you ever argue for rejected cartoons?

CHAST: I resubmit them, and sometimes I rework them. If I really like a cartoon, I’ll just resubmit it and resubmit it until there are like six rejections on the back. At that point it’s like, forget it.

GEHR: Is it tough to have cartoons rejected?

CHAST: Oh yeah, all the time. You can find me in the second volume of The Rejection Collection.

GEHR: How many rough cartoons do you usually draw during those two days?

CHAST: About five or six. When I started it was probably more like ten or twelve, which went down when I had kids. Some of them are long, but a two-page thing still only counts as one. It's that ridiculous.

GEHR: You were probably the first New Yorker cartoonist without orthodox drafting skills. How did readers, not to mention other artists, react when you started appearing in the magazine?

CHAST: Lee told me that when my cartoons first started running, one of the older cartoonists asked him if he owed my family money. And at my first New Yorker party, Charles Saxon came up to me and had things to say about my drawing style. He even asked me, “Why do you draw the way you do?” And I said, “Why do you draw the way you do?” Why do you talk the way you do? Why do you dress the way you do? Why is your handwriting the way it is? I don’t know. I’m aware that a lot of people probably hate my stuff. But I hate a lot of people's work, too. Everybody has their taste.

GEHR: How much of an affinity did you feel with the underground comics scene?

CHAST: A kid my age had some Zap comics when I was young. But I didn't feel like I fit in with underground cartoonists after I was sixteen or so. There may have been underground work in the seventies, but I wasn’t that aware of it in ’77 and ’78.

GEHR: I get the impression you weren’t particularly countercultural growing up.

CHAST: I kind of wanted to be, but I didn’t cut it in some way. Being a whole-hearted hippie or punk or whatever takes a true-believer sensibility I don’t have. I would like to feel earnest about something, but it’s hard to feel that way.

GEHR: You do more different types of cartoons than almost anyone else I can think of, including single-panel gags, four-panel strips, autobiographical comics, and documentary work.

CHAST: It's ADD. The formats are different but the style is similar.

GEHR: They also vary a lot in terms of how much writing you do – from none at all to rather a lot. I'm thinking about the two long journalistic pieces about lost luggage and the alien abduction conference in Theories of Everything. How did you get those assignments?

CHAST: DoubleTake magazine sent me. Such wonderful experiences. I love stuff like Stan Mack's "Real Life Funnies."

GEHR: Do you get most of your material from so-called real life?

CHAST: I jot things down on pieces of paper, and I have a little box of ideas. I’m not organized enough to have a notebook, so it has to be little pieces of paper, evidently. I pull them out when I sit down to do my weekly batch. Sometimes I do cartoons from those ideas, and sometimes they lead to other ideas. I get ideas from all kinds of places, like something my kid said, an advertisement, or a phrase I've heard. It really varies. It might be something someone did that really annoyed me but actually made me laugh after I thought about it.

GEHR: Having to constantly generate ideas can be very hard work.

CHAST: Well, yeah. The New Yorker put a number of us on hiatus this fall. We were told not to submit for a few weeks because they'd overbought and had a lot cartoons they wanted to use up. I wound up writing a Shouts & Murmurs humor piece about eating bananas in public. Trying something different was really fun. I wrote another piece that only appeared online about my friend’s father. He kept track of every meal he ate over twenty years on index cards. And I started a book about phobias that's going to be published by Bloomsbury in the fall. It's called What I Hate: From A to Z.

GEHR: What’s your favorite phobia?

CHAST: Balloons.

GEHR: Is there a technical term for balloon phobia?

CHAST: It's not just a funny list of phobias like you can find online. These are all mine. I really do hate balloons, and I've hated them since I was a kid. I don’t think it’s a common phobia. I'm afraid of someone popping them. I hate that. I don’t worry about Mylar balloons at all, but if I see latex balloons, I don’t want to be in the room with them. So now people are going to send me balloons! “Hello, Roz. I know you like balloons sooo much!”

GEHR: I'm suspecting you weren’t much fun at kids' birthday parties.

CHAST: No, I wasn’t – for so many reasons.

GEHR: Birthday parties actually contain nearly limitless phobia possibilities.

CHAST: Take Pin the Tail on the Donkey. You have to be blindfolded, but what if somebody stabs you with a rusty pin? You'd get lockjaw. It's terrible.

GEHR: We were talking about your process and got distracted in the idea stage.

CHAST: Then I assemble my batch. I mainly work on New Yorker material, but I have other projects going, so I tend to work on New Yorker stuff on Mondays and Tuesdays. I don’t schedule anything those days. I lock myself up with my little ideas and just stay in here and work. I don't put myself through that nauseating experience of looking at someone's face while they go through your stuff. Ugh! It's just horrible! It gives me the cringes to even think about it. I find it disgusting and embarrassing for all concerned. And some of my stuff takes a little while to read. So I feel better that they should look at it in private when they have time; when I’m not sitting there. So first I Xerox them, because of course the Bristol board won’t go through the fax machine. Then I fax everything in Tuesday evening. I work on books and my other projects the rest of the week. Fascinating, isn’t it?

GEHR: I like how you mock suburban life from an urban sensibility, and vice versa. But what's your real problem with suburbia? You seem to fit right in.

CHAST: I don’t belong here!

GEHR: It can't all be like the napkin-folding classes you drew in Theories of Everything.

CHAST: Oh, God, that was just fucking incredible. And real. But I had to learn to drive when me moved out here. I’m glad I live here. I feel very lucky, and I’m not ungrateful for many things. I love Richfield. My kids got a great education here – I think – and seemed more or less happy. But, yeah, suburbia is…kind of weird.

GEHR: You've adapted the Ukrainian pysanka egg-decorating tradition to your own style by painting Chast-ian characters on them. How do you make those things?

CHAST: I always wanted to learn how to do it, and somebody up here showed me how. It's a wax-resist kind of thing, like batik. You melt a little wax in these things called a kistka and draw on the egg with the melted wax, then you dip it into different dyes, which don't color the part you've drawn on. You start with the lightest colors and build up to the darker, like batik. At the end, after you've worked on it for hours and hours, you sickeningly punch a hole in the egg and use the kistka to blow out the yolk and stuff. Then you carefully melt all the wax off the egg, so only the colors remain. I've had them break at every stage of the game. I haven’t done it in more than a year. I go through phases. I went through one big phase, and then I didn’t do it again for a couple of years. Then I went through another big phase, and now I’m on hiatus. I went through a big origami phase, too. I make kusudamas, which are Japanese floral globes.

GEHR: Where did your work ethic come from?

CHAST: Um, do I have one? Probably from not being an heiress. Once the topic of the kind of paper we use came up with Sam Gross. He uses typing paper and I use Bristol, because sometimes I put washes on things, as I have since I started. And I remember him looking at me like I was nuts and saying, “What are you? An heiress?"

GEHR: Do New Yorker cartoonists have anything in common?

CHAST: The most wonderful thing about them is their different voices, which is what the magazine's known for. Think about the greats: George Booth, Charles Addams, Helen Hokinson, Mary Petty, Gahan Wilson, Sam Gross, Jack Ziegler, and Charles Saxon all have different comic and esthetic voices. I could name dozens more. Maybe the way they're surrounded by all that type unifies New Yorker cartoonists in a funny way. New Yorker cartoons can be very timely but also not, yet somehow they reflect their time even if they're not addressing the week's events. Maybe it's because cartoonists can do what they want; they aren’t told what to do by an editor who wants all of an issue's cartoons to be on a specific topic. The New Yorker has let me explore different formats, whether it’s a page or a single panel, and that's very important to me. If I had to do a newspaper strip where it’s boom, boom, punch line, I would kill myself. I'm amazed people can do this without feeling like they’ve just gone to sleep.

GEHR: And yet cartoons are in decline. They used to be the gateway drug to reading magazines for an entire generation.

CHAST: Absolutely. I used to think of cartoons as a magazine within a magazine. First you go through and read all the cartoons, and then you go back and read the articles. It’s like I’m reading The New Yorker Magazine of Cartoons first. Reading it online is very different.

GEHR: What are the tools of your trade?

CHAST: I use Rapidographs to draw and some other pens, mechanical pencils, and brushes. That’s pretty much it. I’m left-handed, so as much as I would love to be a person who uses Speedball pens, it doesn't work for me. When I drag the point like this, it feels great. But I tend to push the nib.

GEHR: Who are some of your other influences?

CHAST: My two greatest influences are [William] Steig and [Saul] Steinberg. Steinberg is so inventive, so wonderful. And I just wrote an introduction to a book of Steig's unpublished drawings for Abrams. His wife, Jeanne, has thousands of them. I love George Price and George Booth, as well as Leo Cullum and Jack Ziegler. I loved Ed Sabitzky, a friend of Sam Gross's who did stuff for National Lampoon. I Love Gahan Wilson, of course. Harvey Pekar and Richard Taylor. And Gluyas Williams, love the beautiful weird eyes, just incredible. Edward Gorey, the best. And Jules Feiffer. I love Mary Petty, who's kind of creepy.

GEHR: Where did you learn to do color?

CHAST: I use watercolor and gouache. I love watercolor because you can really build up the tones. I think Tina Brown first suggested using color on the inside of the magazine, although, the first cover I did was in 1986, when William Shawn was editor.

GEHR: The ice cream cover. The New Yorker seems to be reintroducing color. Have been encouraged to do more of it?

CHAST: Yeah, there's been some of that. I don’t like it when it’s kind of random. I use it in longer pieces because it’s more fun to look at if it’s in color. But small things don’t really need to be in color. I don’t think it adds to the funniness but it makes your eye happier, you know?

GEHR: What are your favorite cartoon tropes?

CHAST: I love anything to do with fairytales, like the Three Little Pigs or Rapunzel. Also children’s books. This week’s issue has a cartoon by me about Timmy Worm and Jimmy Caterpillar. They’re friends, but when Timmy sees Jimmy turn into a butterfly, it really freaks him out. I'd love to do a desert-island gag, which I've never done. I love the end-of-the-world sign guys and tombstone gags. Anything to do with death is funny.

GEHR: Did you ever hang out with Charles Addams?

CHAST: No, I only met him in the New Yorker offices. His stuff was the first grown-up humor I really loved. It was dark and it made fun of stuff you weren’t supposed to make fun of. I loved "sick" jokes when I was a kid.

GEHR: If you taught cartooning, what would you tell your students?

CHAST: I would probably be more like Gary Panter than a person who taught any usable skills: If this is what you really love to do, just keep doing it. Part of me wants to say, "If I could figure it out, you can figure it out." The New Yorker doesn't have drop-off days anymore, but I’m sure websites have ways to submit material. Or maybe start your own website. There are cartoon collectives and people who put out little zines and stuff. The question I have is: Can people make a living doing it? I can’t make a living only doing New Yorker stuff. Most students probably know they’ll probably have to get another job to support their cartooning. Which is not too bad, you know?

GEHR: What younger cartoonists knock your socks off?

CHAST: I don’t know how much younger they are. I love Chris Ware, Daniel Clowes, the Hernandez brothers, and Alison Bechdel. I wish I could say I knew more. A lot of graphic novels I’ve seen are knock-outs. So great, so interesting, and so beautifully drawn. I’ve very much pulled toward that now.

GEHR: Are you thinking about doing something long-form?

CHAST: Something about my parents is going to be my next big project, actually. They were born in 1912 and my mother just passed away last year. She was ninety-seven.

GEHR: What other projects are you working on?

CHAST: I’m finishing up a second children’s book based on my birds. Too Busy Marco, the first one, came out last year.

GEHR: You've always done autobiographical comics, of course. Who could forget your gruesome account of acquiring a vicious family dog?

CHAST: People think that story was an exaggeration, but it was actually toned down. It was worse. At one point the dog twisted a bone in her hip. We took her to the vet, who had to muzzle her because she was going so crazy. All these horrible things happened over a six-day period. I hardly even mentioned her breeders because I didn’t want to get into trouble with them.

GEHR: You've also done comics about Brooklyn before.

CHAST: That was for The New Yorker's Journeys issue. The thing about growing up in Brooklyn is that your neighborhood was bounded by certain blocks, and you didn't go outside them even to go shopping. My father didn’t drive but my mother did, and she was a nut. If I asked her, “Mom, how come we shop on 18th Avenue? Why don’t we ever shop on 16th Avenue?” she’d go, “You can shop on 16th Avenue when you’re grown up!” You would get screamed at if you left our safe little area.

GEHR: A lot of your cartoons have a very distinct sense of place.

CHAST: I have an odd little book Helen Hokinson did about going out to buy a mop. I like that she has this whole world, and I feel like I can go into that world. It’s not generic; it’s very specific. I don’t like cartoons that take place in nowhereville. I like cartoons where I know where they’re happening. I have to feel like they’re real people. I can’t even look at daily comic strips. And I hate sitcoms because they don’t seem like real people to me, they're props that often say horrible things to each other, which I don't find funny.