“The cartoonist, however inflected, inflated, or addicted, remains perfectly aware that he or she is nothing more than this week’s stand-up comic battling as always for attention, just reward, a better place on the playbill, full copyright, and the hearts of a public who have paid to be diverted in the old music-hall tradition in which comic drawing was born.”

—Ronald Searle

Ronald Searle was born into a lower-class home in Cambridge, England on March 3, 1920. His father was a porter at the main train station and his mother took in the occasional boarder to help make ends meet. He had a younger sister, and both of them often visited the various museums and libraries that populated that erudite city.

Searle started drawing at the age of five. His first exposure to the world of caricature and cartooning came from seeing the works of the great Max Beerbohm at the Fitzwilliam Museum. He was also an early fan of the painters William Blake and J.M.W. Turner, and, on the lowbrow side, he was devouring pages of British humor magazines such as Punch and The Tattler.

At the age of 15, he decided to stop going to regular school and took on a series of jobs to help pay for classes at the Cambridge School of Art. The jobs did not work out, but his parents helped as best they could to pay his tuition. At the same time, an opening appeared for a cartoonist at the Cambridge Daily News, which Searle jumped on. His first published work appearing in that paper on October 26, 1935, and 194 more of his cartoons followed over the next four years.

He stayed at the Cambridge School of Art, becoming a full-time student there in September 1938, after acquiring a one-year scholarship. But as war clouds gathered in Europe in 1939, he and some of his anti-fascist friends decided to volunteer for the Territorial Army, which Searle thought would allow him a better chance to determine his fate should war break out.

He registered for the Royal Engineers, and in September 1939 was called up in response to Germany's invasion of Poland. From late 1939 to October 1941, Searle was based in various locations throughout England and Scotland. He still submitted work to magazines, and his first national exposure came in July 1940 with a cartoon in the London Opinion.

He registered for the Royal Engineers, and in September 1939 was called up in response to Germany's invasion of Poland. From late 1939 to October 1941, Searle was based in various locations throughout England and Scotland. He still submitted work to magazines, and his first national exposure came in July 1940 with a cartoon in the London Opinion.

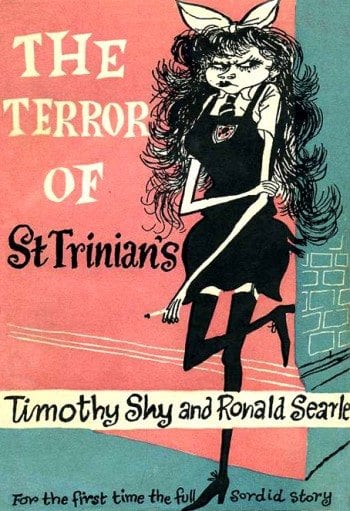

While in Scotland, Searle became acquainted with a local artist whose two daughters went to St. Trinnean’s, a school whose name would become synonymous with Searle’s, albeit under a different spelling and with Searle’s dark but humorous view of its students. The first St. Trinian’s cartoon was published by Lilliput in 1941, selected from a batch of unsolicited cartoons sent to the magazine’s editor, Kaye Webb. Thus began his British legacy, which eventually would annoy him no end.

On October 29, 1941, Searle set sail with his Royal Engineers division on a ten-week voyage that landed them in the British colony of Singapore on January 13, 1942. With him he took a cherished volume of drawings by the German artist and cartoonist George Grosz, a large influence on Searle’s style and views about humanity.

One month later, the Japanese overran Singapore, and Searle found himself in the Changi POW camp with 50,000 of his fellow soldiers. It was the largest surrender of British troops in the country’s history and Searle was right in the middle of it.

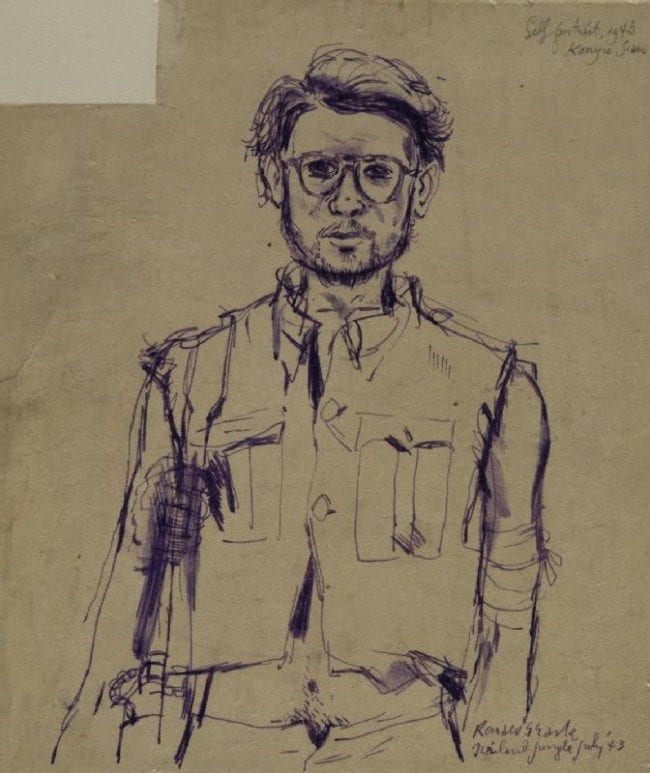

Searle continued to draw, with his fellow prisoners finding him paper and various forms of writing implements. He likewise devised ways to create his own ink, including using dyes meant for staining microscope slides. He was in Changi until May 1943, when he was sent out to work in the harsh conditions of the Thai and Burmese jungles to build a railway so the Japanese could transport troops and material for a potential invasion of India. One of the rivers the prisoners had to cross was the River Kwai, basis for the famous movie directed by David Lean.

For seven months, Searle worked on the railway line, subsisting on a single bowl of rice per day. He wound up being one of the lucky survivors—over two thirds of those working with him died during the construction, for a toll of over 100,000 deaths.

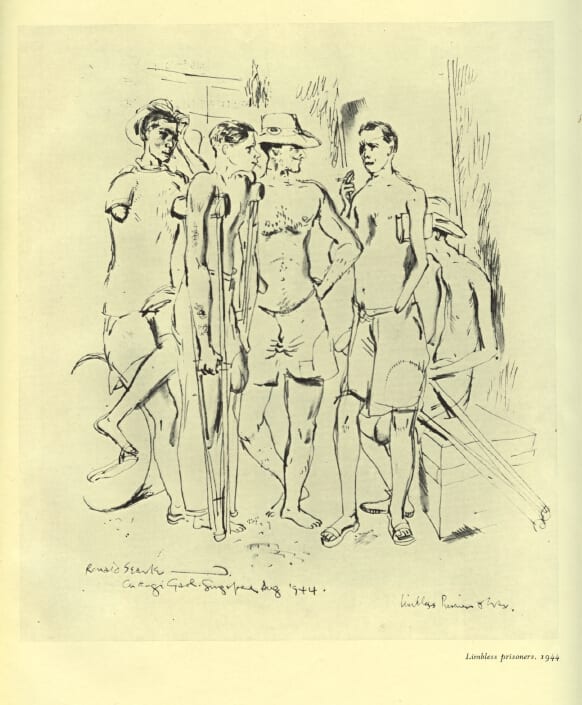

He returned to Changi and continued to draw what he experienced, hiding his drawings in the hospital beds of cholera and typhus patients, where he knew the Japanese would not dare to look for them. Being a POW under the Japanese was Searle’s first reportage “assignment,”and his drawings bear witness to the brutal treatment the prisoners received. Searle's activity was fraught with danger, as if the Japanese soldiers had discovered his trove of drawings, they would have killed him without hesitation.

Changi was liberated in August 1945, but the experience never left Searle. He lost many friends and had his freedom taken from him for three and a half years. During his incarceration, Searle succumbed to nearly every disease known to the jungle, including malaria and beriberi, yet somehow survived.

Upon his return to England, he reconnected with Kaye Webb of Lilliput, and the magazine began publishing his cartoons. In December 1945, over three hundred of his war-time sketches were shown at his alma mater, the Cambridge School of Art. Out of this exhibition came his first book of war drawings, published in 1946, as well as an offer to go to Yugoslavia in 1947 and report on how the country was rebuilding after the war.

Searle continued to contribute to Lilliput, London Opinion, The Tattler, and other periodicals. He also found time for a romance with Kaye Webb, whose contacts in the magazine world surely helped Searle’s career. The couple had an out-of-wedlock pair of twins in 1947, and married in 1948. The arrangement was unusual for its day, as Webb was five years older than Searle.

Searle’s published his first book of cartoons, Hurrah for St Trinian’s and Other Lapses, in 1948. He continued putting out new material until 2011; his bibliography comprised over eighty-five books of cartoons, illustration work, and reportage.

He expanded his cartoon and reportage work by undertaking theater reviews in 1948 supplying caricatures and illustration for Punch, which had begun publishing his cartoons in 1946. He continued contributing theater work to Punch until 1960.

His St. Trinian's series brought him his lasting fame in England. There were six books in this series published between 1948 and 1959, and four movies were made about the rambunctious schoolgirls. But this broad fame for a narrow body of work overshadowed what he thought were much better accomplishments. Searle eventually blew up St. Trinian’s with an atomic bomb.

His St. Trinian's series brought him his lasting fame in England. There were six books in this series published between 1948 and 1959, and four movies were made about the rambunctious schoolgirls. But this broad fame for a narrow body of work overshadowed what he thought were much better accomplishments. Searle eventually blew up St. Trinian’s with an atomic bomb.

During the 1940s and 1950s, Searle, Andre Francois, and Saul Steinberg developed similar stripped down styles, using delicate lines, surreal backdrops, and an absurdist view of the world. Steinberg and Searle in particular fed off of one another, and some of Searle’s works could easily be confused for Steinberg’s.

But Searle’s influences also reached across the history of British caricature. He felt closest to William Hogarth, though his line work was much more apparently similar to that of Thomas Rowlandson and, in particular, James Gillray, two other Searle favorites. The great H.M. Bateman and Strube were cartoonists contemporary to Searle's early career that he additionally admired. As his economic stature escalated, Searle began to collect both prints and original works by these British cartoonists, as well as by Robert Newton, George Cruikshank, Cruikshank’s brother Robert, and the famed Punch cartoonist John Leech.

In turn, a number of cartoonists cite Searle among their influences, extending the long lineage the great British caricaturists from Hogarth in the 18th Century through to today. Arnold Roth, Richard Thompson, Ralph Steadman, Ann Telnaes, Nick Galifianakis, Scarfe, Posy Simmonds, Matt Groening, and Martin Rowson all cite Searle as a major inspiration, with Groening saying it was Searle’s wicked St. Trinian's girls and other cartoons that led him to create the sometimes bleakly humorous worlds of Life is Hell and The Simpsons.

Searle began to reach in international audience in the 1950s and 1960s. His cartoons for various publications were syndicated around the world and especially within the British Commonwealth. In the United States, he worked for Holiday, Life, Look, TV Guide, The New York Times, and The Saturday Evening Post, among others, and also drew illustrations for a number of commercial clients whose ads ran in American magazines.

He began submitting cartoons to The New Yorker about the time Holiday and its lucrative reportage assignments stopped in 1970. Searle drew cartoons and special assignments for the magazine, as well as nearly forty covers, working for them well into the 1990s.

He moved to France in 1961, tiring of the St. Trinian’s connection and of England in general, living in Paris until 1975, when he and his new wife then moved to Provence, where he lived until passing away last week.

Searle also worked in the world of animation, creating a promotional cartoon for Standard Oil, as well as working on the animated opening credits to such movies as Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines, Scrooge, and Those Daring Young Men In Their Jaunty Jalopies, , and his drawings and designs provided the basis for the animated film Dick Deadeye, directed by the former UPA animator Bill Melendez.

Searle also worked in the world of animation, creating a promotional cartoon for Standard Oil, as well as working on the animated opening credits to such movies as Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines, Scrooge, and Those Daring Young Men In Their Jaunty Jalopies, , and his drawings and designs provided the basis for the animated film Dick Deadeye, directed by the former UPA animator Bill Melendez.

His last book of new original material was Let's Have a Bite!: A Banquet of Beastly Rhymes, the second of two collaborations with Robert Forsythe. Some of the originals for this book were on exhibit at the Chris Beetles Gallery in London this past June. The originals were stunning to see, unlike those of the elderly Herblock and Charles Schultz; time did not in any way impact the sureness of his line, sense of humor, or overall compositional skills.

Searle's lifetime accolades were of an international nature. Showing that they were still firmly implanted in the British psyche, his St. Trinian's girls were made once again into a movie in 2007, which the ever consistent Searle did not like. Perhaps in an attempt to make amends of sorts, the crown appointed him Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 2004. In 2010, the Cartoon Museum in London held a lifetime retrospective, displaying works from his entire career as well as some of his private holdings of original drawings by Leech, Gillray, the Cruikshanks, and Rowlandson.

In 1973, an exhibit of over 250 of his originals was shown at the Bibliotheque Nationale de France, the first for a non-native. In 1995, at the age of 75, he began a series of political cartoons for the French newspaper, Le Monde, which were collected in a book published in 2002. The French also honored him in 2007 with the French Order of the Legion of Honor, France’s highest honor for an artist.

Here in the United States, the National Cartoonists Society voted Searle the Rueben Award for 1960, the first non-American to win the honor. He was also awarded the NCS Award for Advertising Illustration in 1959, 1965, 1980, 1986 ,and 1987.

As a final thumb in the nose of his native England, Searle’s extensive archives, book collection, original cartoons, and art collection were all donated to the Wilhelm Busch Museum in Hanover, Germany in 2010, where they will be in good company with the Busch Museum holdings of Gillray, Hogarth, and Daumier.

There is no question that Searle spent his 75 years on the “music-hall stage” of the cartoonist’s life well. He excelled in all aspects of his career, which encompassed humor cartoons, political cartoons, magazine and book illustration, reportage, and animation. The results were not only a timeless body of work but the knowledge that he attained what is arguably the greatest height a cartoonist can attain, that of being an influence on those who came after him. No greater honor can be bestowed upon any one in the comics field.

For those who are familiar with his work, his loss is indeed a great one. For those just now hearing about Searle’s life and work, by all means, get some of his books, go sit in front of that music-hall stage, and enjoy the show.