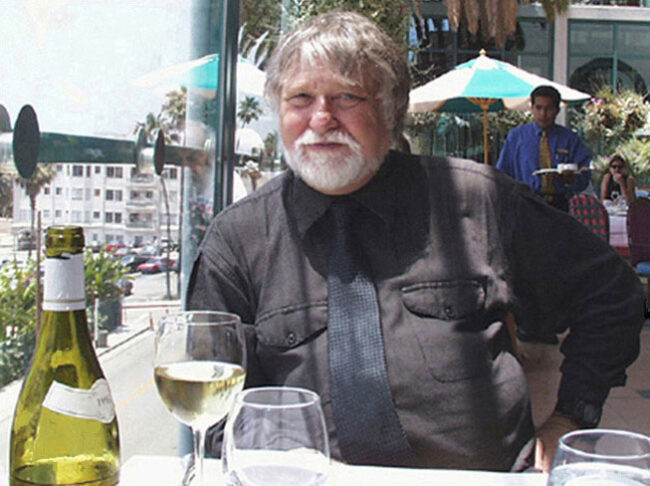

Ron Cobb — editorial cartoonist, ecology-symbol creator, Disney animator and production artist for just about every major science-fiction film you’ve seen in the past 50 years — passed away on his 83rd birthday, Monday, Sept.21. In the course of one of the most varied and interesting careers of any contemporary illustrator, Cobb’s artistic vision and creative ideas illuminated multiple rooms in the house of Western pop culture. A highly regarded political cartoonist during the ’60s and early ’70s, he moved on to film design and illustration in the early 1970s and was both highly influential and well respected throughout the industry for decades, with a reputation for logical designs and meticulous attention to detail.

Ron Cobb — editorial cartoonist, ecology-symbol creator, Disney animator and production artist for just about every major science-fiction film you’ve seen in the past 50 years — passed away on his 83rd birthday, Monday, Sept.21. In the course of one of the most varied and interesting careers of any contemporary illustrator, Cobb’s artistic vision and creative ideas illuminated multiple rooms in the house of Western pop culture. A highly regarded political cartoonist during the ’60s and early ’70s, he moved on to film design and illustration in the early 1970s and was both highly influential and well respected throughout the industry for decades, with a reputation for logical designs and meticulous attention to detail.

After attending Burbank High School, but possessing no formal art training, the young Ron Cobb was hired by Disney Studios to work as an “inbetweener” on Sleeping Beauty (1959) before graduating to working art breakdowns for the film. Unemployed after Sleeping Beauty wrapped production, he then went on to a variety of different jobs, including being a mail carrier, a sign painter, and an assembler in a door factory. He was drafted in 1960 and spent the next two years conveying classified documents to military installations in the San Francisco area. To avoid being assigned to the infantry, Cobb signed up for an additional year and was sent to Vietnam, but as an illustrator, not a ground-pounder. During his time in Vietnam, he worked as a draftsman for the Signal Corps, which allowed him to further enhance his natural artistic skills, though there are unconfirmed rumors that Cobb was actually working in Military Intelligence at the time, something he hinted at to friends years later.

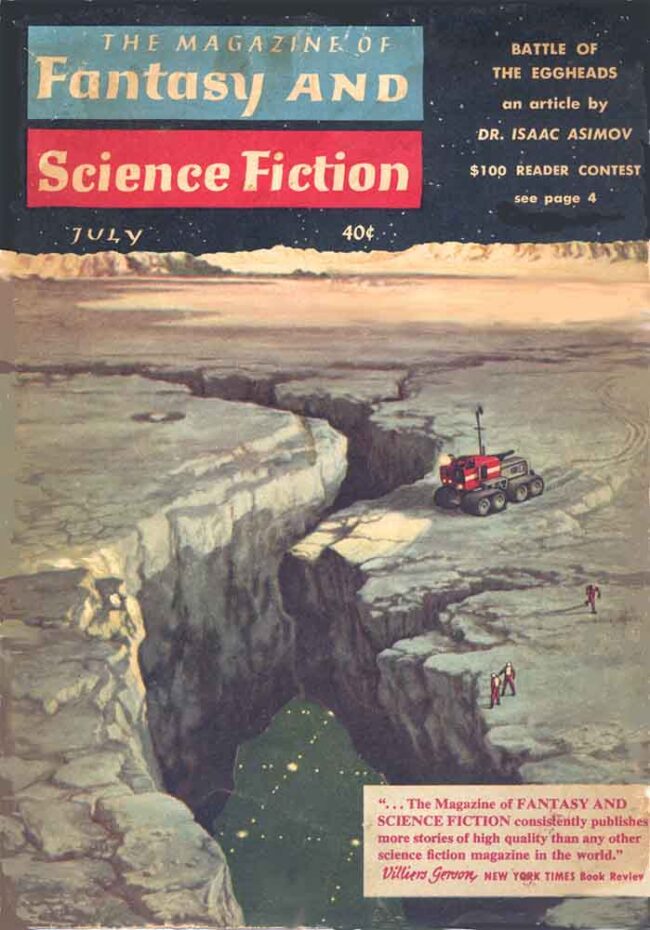

Upon returning to the U.S., Cobb spent the next two years working as a freelance artist, including selling cover paintings to science-fiction pulps like The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. In 1965, as Cobb recounted on his website, Roncobb.net:

One evening in the mid-sixties I accompanied a writer friend to the editorial office of an alternative “underground” newspaper that was just beginning to circulate around the streets of Hollywood, a weekly called The Los Angeles Free Press. My friend was picking up a manuscript he had submitted to the paper and thought I might be interested.

We arrived at the Fifth Estate coffee house, at the east end of the Sunset Strip. It was a popular hangout for aging beatniks and youthful hippies. I knew the place fairly well and occasionally hung out there myself. However, I was surprised when my friend led me to the back of the table service area, through a door I had never noticed, and down a flight of stairs into a dimly lit basement. The place was cluttered with composing tables, various machines, and old furniture.

This is where I met Art Kunkin, the publisher and editor of the “Freep,” sitting at an ancient roll-top desk under a single light bulb, looking for all the world like a young Leon Trotsky. After a short tour around the office, I suddenly realized that I could submit my cartoons and get them published with limited censorship, so long as I didn’t ask to be paid.

I immediately offered Kunkin one of my rejected cartoons from Playboy Magazine. (I always carried them with me in a beat-up old briefcase, you never know) and joined the staff of the Free Press as the editorial cartoonist for the next five years.

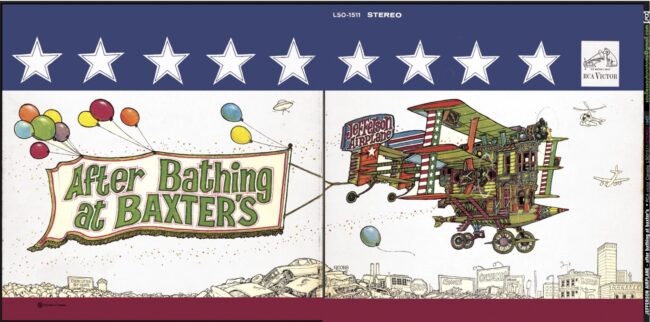

The Free Press, or “Freep” as it was familiarly known, was one of the earliest underground newspapers espousing radical politics, and at first, really did operate out of a coffeehouse basement on Sunset Strip. Cobb quickly began contributing editorial cartoons that his friend William Stout later described on his Worlds of William Stout website as, “unlike anything else being done in that genre.” The editorial cartoons that Cobb drew for the Freep over five years were distributed to more than 80 alternative press outlets all over the U.S., Europe, Asia and Australia, including many famous American underground papers like The Berkley Barb, The East Village Other, The Chicago Seed, and others. The editor of Famous Monsters of Filmland, Forrest J. Ackerman, became Cobb’s agent and commissioned him to paint covers for Famous Monsters and its companion title Monster World, as well as some album cover art. In 1967, Cobb created the art for the Jefferson Airplane album After Bathing at Baxter’s. Another famous assignment from this period was a poster that showed Los Angeles falling into the ocean after a massive earthquake. Cobb was prolific and talented as an editorial cartoonist, and his work was reprinted in The Mother Earth News and several paperback collections, RCD-25 (1967), Raw Sewage: Mah Fellow Americans (1968), Unprocessed Cartoons (1970), My Fellow Americans (1971), The Cobb Book: Cartoons (1975), and Cobb Again (1976), but this career was far from lucrative. His editorial cartoons addressed themes of environmental degradation, rampant consumerism, racism, the specter of nuclear holocaust and the increasing militarization of American society. His paintings and color art are also showcased in the book Colorvision. All of his books are long out of print and command high prices on the used-book market.

In 1969, Cobb made what was undoubtedly one of his most important contributions to world culture: he designed the ecology symbol and the ecology flag. In a gesture of public-spiritedness, he put his designs in the public domain so that they could be used by anyone. Cobb’s original design artwork was deemed so significant, that it’s on permanent display at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C.

In 1969, Cobb made what was undoubtedly one of his most important contributions to world culture: he designed the ecology symbol and the ecology flag. In a gesture of public-spiritedness, he put his designs in the public domain so that they could be used by anyone. Cobb’s original design artwork was deemed so significant, that it’s on permanent display at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C.

Because his work was so widely syndicated, it was seen in Australia by his future wife, Robin Love, who invited him to do a lecture tour there in 1972. Cobb was accompanied on this tour by his friend, legendary folk musician Phil Ochs, who provided the musical interludes to his lectures. Cobb and Love married in 1973, with Cobb opting to stay with her in Sydney, Australia, drawing editorial cartoons that reflected the problems and issues in Australia. Even though his cartoons were highly regarded, Cobb made very little money from them, and after his return from Australia, Robin started a small restaurant that supported the couple for several years. Later in 1973, Cobb, by now disenchanted with trying to make a living as a cartoonist, moved into film production, designing the spacecraft in John Carpenter’s first film, Dark Star, on an International House of Pancakes napkin at the behest of Dark Star writer Dan O’Bannon (who also played Sgt. Pinback in the film). Around this time, Cobb painted a scene of a desert traveler riding on a huge lizard for screenwriter/director John Milius. George Lucas later saw this and incorporated it as the giant Dewback Lizards that the Storm Troopers rode on Tatooine in the first Star Wars film. Lucas also hired Cobb to create some of the exotic alien designs seen in the film’s iconic cantina sequence. Following his work for Lucas, Cobb was hired, along with Alien creator H.R. Giger, and famed French cartoonist Moebius (Jean Giraud) to create designs for Alejandro Jodorowsky's aborted version of Dune during the mid-’70s, alongside O’Bannon, who worked on computer graphics for the film. According to Cobb, Jodorowsky didn’t like any of the vehicle designs Cobb created, deeming them, “too American, too ‘NASA’”. After this, Cobb moved on to design work for Ridley Scott’s seminal Alien, again working alongside O’Bannon, Moebius and H.R. Giger. O’Bannon wrote the original screen story and was credited with the final screenplay, as well as creating some computer graphics for the film. Cobb’s contributions to the Alien canon included designs for the exterior and interior of the Nostromo in Alien and the astronaut’s helmets and backpacks. However, Cobb brought more than a fertile imagination and skilled draftsmanship to the projects he worked on. He is credited with coming up with the idea of having the Alien blood be corrosive, which prevented the hapless Nostromo crew from simply blowing it up or shooting it since the creature’s blood would’ve eaten through the ship’s hull. He also contributed design work to the sequel, Aliens (1986), greatly contributing to the film’s believable futuristic technology, especially his design for the earth colony complex and its attendant reactor/atmosphere factory.

After working on Alien, Cobb was a production artist on Spielberg’s Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) and designed the Nazi flying-wing aircraft. John Milius’s Conan (1982) was the first film on which he was credited as the production designer. His armor and weapons designs drew mightily on the work of Frank Frazetta, but Cobb amped up the macho atmosphere even more. Fellow cartoonist/film artist William Stout, who first worked with Cobb on Conan, reported: “… the best two years of my life in film were the two years I spent in a room with Ron Cobb.” The two became lifelong friends after this and he had high praise for the quality of Cobb’s imagination: “It was like sitting next to a fountain that gushed great ideas all day long, seemingly effortlessly. I learned an enormous amount from Rob, much by example.” Cobb’s next stint as a production designer was on The Last Starfighter (1984), for which he designed virtually all of the alien ships. Cobb somehow convinced the Pentagon to grant him the use of a pair of Kray supercomputers, which were needed to generate the detailed imagery for the film’s space battles. The Krays were the fastest computers in the world at the time and required a cooling system that took up an entire building next door. Cobb was one of the first film artists to plunge into creating his images on a computer and Stout credited him with always being at the vanguard of adopting new filmmaking technologies.

In 1986, Cobb came up with the design for the opening credits of Spielberg’s Amazing Stories and then went on to work on three films that all came out in 1989, Leviathan, Meet the Hollowheads and The Abyss. For both Leviathan and The Abyss, Cobb designed detailed, believable underwater habitats and much of the diving gear and other underwater equipment, including two working Remotely Operated Vehicles. The total extent of his production design work in the film industry is truly staggering. Cobb contributed art and designs to Close Encounters of the Third Kind (the revised version), Total Recall, True Lies, My Science Project, Robot Jox, The Rocketeer, Space Truckers, Titan A.E., The Sixth Day, District Nine, John Carter of Mars, and the Firefly TV series. He also worked on the film version of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and became good friends with original author Douglas Adams. Cobb also helped in the design of the DeLorean time machine for Back to the Future, one of many, many iconic designs that sprang from his protean imagination.

Although he’s not much associated with Spielberg’s E.T., it was Cobb who came up with the original idea for the film, based on a true-life UFO incident from the 1950s. The film was to be called Night Skies and it was to be Cobb’s directorial debut (at the behest of Steven Spielberg) and was supposed to be written by John Sayles. The project was canceled during the pre-production phase when it was realized the budget was spiraling out of control. However, Spielberg liked the idea enough to have it reworked into E.T. The Extraterrestrial, which went on to be one of his most popular and successful films. Lest you feel too bad for Ron Cobb at losing the project, a careful reading of his original contract by his wife revealed that he was entitled to a kill fee for not directing, as well as participation in the film’s licensing, which earned him a tidy $400,000. Of the finished film, Cobb was frankly unimpressed, despite its wide popularity, calling it, “a banal retelling of the Christ story, sentimental and self-indulgent, a pathetic lost puppy kind of story.”

Cobb’s talents extended beyond art and film design. He and his wife co-wrote an episode of the 1980s incarnation of The Twilight Zone, and he wrote and directed an Australian film called Garbo about a pair of trash collectors who were obsessed with silent film star Greta Garbo. He contributed ground-floor stories and designs for Rocket Science Games, which launched in 1992. Cobb was awarded the very first Lifetime Achievement Award for Concept Design for his body of work. At the end of his life, he was suffering from Lewy Body Dementia, which eventually confined him to a full-time care facility in Sydney, Australia, and eroded his memories so badly that he was unable to recognize his wife and son at the end of his life.

Cobb is survived by his wife of 48 years, Robin Love, and by his son, Nicky.